Loss grouping and imputation credits

AGENCY DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) has been prepared by Inland Revenue.

It provides an analysis of options to address the current tax disadvantage created by the interaction of the loss grouping and dividend imputation rules for non-wholly owned companies that are part of a commonly-owned group. This tax disadvantage arises from the claw-back of the benefit of loss grouping when the recipient of the loss doesn’t have sufficient imputation credits to impute a dividend to its shareholders resulting in additional tax being required to be paid.

The tax disadvantage is an unintended outcome of the interaction between the two sets of rules, is inconsistent with current tax settings and leads to sub-optimal decision making (i.e. it creates an incentive for 100 percent, rather than partial, corporate acquisitions in circumstances where this may not be the most economically efficient outcome).

Analysis of the status quo involved reviewing a sample of the population of all companies that undertook a loss offset or subvention payment. This sample was reviewed to check the ownership structure and, if these companies were non-wholly owned, whether they paid unimputed dividends to their shareholders.

There are two key constraints on the analysis:

- Because of data limitations it is not possible to ascertain the reasons why companies may be paying unimputed dividends or how many companies are choosing to remain in a wholly-owned group structure in order to prevent the tax disadvantage arising. Consequently, it is not possible to determine the full extent of the problem.

- A number of assumptions were made in order to determine the likely fiscal impact. The tax disadvantage does not appear to raise significant tax revenue as taxpayers can structure their affairs to prevent the taxation of unimputed dividends. Structuring options to achieve this include: staying as a wholly-owned group; not paying dividends; not grouping losses; or accessing imputation credits from another source. The options in this RIS may decrease tax revenue (owing to unimputed dividends becoming imputed) or increase tax revenue (because new imputed dividends may be paid to a person on a tax rate higher than 28 percent). The fiscal estimates were refined following targeted private sector consultation.

A range of options have been considered and measured against the criteria of economic efficiency, fairness and integrity and coherence whilst minimising compliance costs for taxpayers and disruption to current practices and administrative costs for Inland Revenue. There are no environmental, social or cultural impacts from the recommended changes.

Inland Revenue is of the view that, aside from the lack of information on current ownership structures and dividend payment behaviour, and the difficulty with fiscal estimates, described above, there are no other significant constraints, caveats and uncertainties concerning the regulatory analysis undertaken.

None of the policy options identified is expected to restrict market competition, reduce the incentives for businesses to innovate and invest, unduly impair private property rights or override fundamental common law principles.

Peter Frawley

Policy Manager, Policy and Strategy

Inland Revenue

20 November 2015

STATUS QUO AND PROBLEM DEFINITION

1. The question addressed in this RIS is how to deal with the tax disadvantage that occurs when the loss grouping and dividend imputation rules in the Income Tax Act 2007 are applied by a non-wholly owned group of companies.

Loss offset

2. A company that has at least 66 percent of shareholders the same as another company is referred to as being “commonly-owned”. A company (“the loss company”) can transfer the benefit of a loss incurred to a commonly-owned company (“the profit company”) by undertaking a loss offset or receiving a subvention payment (“a loss transfer”).

3. A loss offset has the effect of reducing the loss of one company and decreasing the taxable profit of another company within a commonly-owned group by an equivalent amount. A subvention payment achieves the same effect by the profit company making a deductible payment (and therefore reducing its net income) to another company in a commonly-owned group. The subvention payment is assessable to the loss company and reduces its loss. Taxpayers in a commonly-owned group can use any combination of loss offsets and subvention payments to transfer the benefit of a loss. The examples in this RIS apply a subvention payment equal to the tax value of the total loss transfer and a loss offset for the balance, this combination provides the loss company with a cash compensation for the value of the losses they have transferred.

4. When considered as a group, the loss transfer will reduce income tax payments required in the current year but will make fewer losses available to offset against future year profits. This reduction in income tax payments means the profit company will generate fewer imputation credits than if the loss had not been transferred.

5. Loss transfers between companies with “substantially the same” shareholders or under common control was originally introduced in the Land and Income Tax Act 1954 as an anti-avoidance measure when New Zealand had a progressive company tax rate. It was designed to prevent a business being broken into a number of separate companies to avoid the higher marginal tax rates.

6. In 1968 the law was amended so that the Commissioner of Inland Revenue no longer had to invoke avoidance to assess group companies (now defined to be companies with 2/3rds common ownership) at the tax rate that would apply to the aggregate taxable income of the group. The corollary of this automatic aggregation of group income was the ability of group companies to use subvention payments to group tax losses. It was originally proposed that grouping of income would occur at 50 percent commonality and subvention payments could be made at 75 percent commonality. Ultimately, the 2/3rds threshold was adopted for both income and losses. New Zealand’s 66 percent commonality threshold for loss grouping is substantially lower than other OECD countries – notably Australia which only allows grouping within a consolidated group (which requires 100 percent common ownership).

Dividend imputation

7. Imputation credits represent a credit for income tax paid by a company and can be attached to a dividend paid by the company to its shareholders. Imputation credits are also assessable to the owner of the company receiving the dividend, but are a credit against tax payable. This system allows the value of tax paid by a company to reduce the tax liability of its shareholders so that the same income stream is not taxed twice. When a company pays a dividend that has imputation credits attached equal to the company tax rate this dividend is known as a fully imputed dividend. When some imputation credits are attached, but less than the full company tax rate, this is known as a partially imputed dividend.

8. When the profit company pays a dividend to its shareholders it will often have insufficient imputation credits to fully impute the dividend because the losses transferred mean less tax has been paid by the profit company. The shareholder will therefore have to pay more income tax compared to if the dividend was fully imputed. When the commonly-owned group and its shareholders are considered as a whole, more tax will be paid than if the loss was not transferred.

The problem

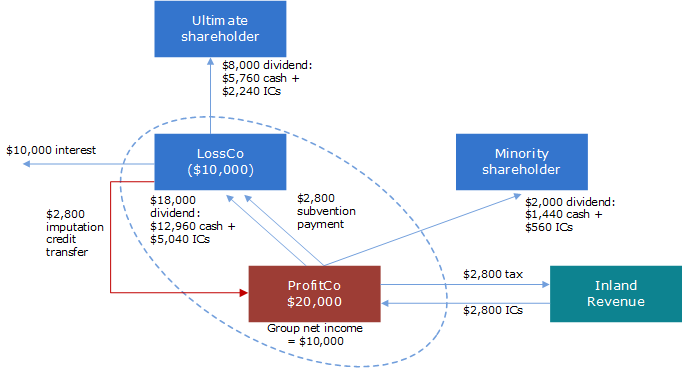

9. Example 1 illustrates how the additional tax arises. In this example a loss company has a 90 percent shareholding in a profit company (which makes it eligible to group losses). All shareholders are assumed to be on a 28 percent tax rate in order to simplify the example.

Example 1

- The loss is transferred from LossCo to ProfitCo via a combination of a 28 percent subvention payment and a loss offset election for the remaining $7,200 tax loss.

- ProfitCo has $10,000 of profit after the loss transfer so pays $2,800 tax. It therefore has $14,400 of cash and $2,800 of imputation credits.[1]

- ProfitCo pays 10 percent of its profits as a dividend to Minority Shareholder. This is $1,440 cash and $280 of imputation credits. This dividend is not fully imputed so Minority Shareholder has to pay extra tax of $202.

- ProfitCo pays 90 percent of its profits as a dividend to LossCo. This is $12,960 cash and $2,520 of imputation credits. This dividend is not fully imputed so LossCo has to pay extra tax of $1,814.

- LossCo pays its $10,000 interest bill and distributes its remaining $3,946[2] as a cash dividend with $1,534 of imputation credits attached.

- This can be shown in a diagram as:

10. The consequences of this transaction are that $4,816[3] of tax has been paid even though only $10,000 of total income was earned. Also, LossCo ends up with $2,800[4] of imputation credits that cannot be used unless additional income is generated without additional tax being paid.

11. This problem does not arise for wholly-owned groups because of the operation of the inter-corporate dividend exemption. The inter-corporate dividend exemption allows a company to pay a dividend to its 100% corporate shareholder without the dividend being included in the recipient company’s assessable income. This exemption recognises that one company wholly-owning another company is economically equivalent to a single company undertaking all of the activities of both companies and there are efficiency benefits in not requiring imputation credits to be tracked across this transaction. The same arguments do not apply to a non-wholly owned group as a company having more than one shareholder means the company and its shareholders cannot be considered as a single economic unit.

12. Because this problem does not arise for wholly-owned groups it creates a tax disadvantage for non-wholly owned groups and incentivises 100 percent ownership, even when - in the absence of tax - it would be economically efficient for a group to include a minority shareholder(s).

13. The root cause of the problem is that losses can be offset between commonly-owned groups whereas the inter-corporate dividend exemption is only available to wholly-owned groups. The tax disadvantage for non-wholly owned groups created by the interaction of these two sets of rules would disappear if these two thresholds were aligned.

Scale and impact of the problem

14. Although this problem influences the ownership structuring decisions of company shareholders, it does not appear to have a large impact on the amount of tax paid. This is because groups can make decisions that prevent income being subject to tax twice such as maintaining a wholly-owned group, not transferring the full amount of losses or not paying dividends.

15. Owing to data limitations there is no reliable way of estimating how many companies may be discouraged from taking on minority shareholders because of the interaction of the loss grouping and dividend imputation rules. This is because we can observe what unimputed dividends have been paid but cannot observe what dividends have not been paid and what wholly-owned groups have not taken on a minority shareholder(s).

OBJECTIVES

16. The main objective is to remove or reduce the tax disadvantage created by the interaction of the loss grouping and dividend imputation rules.

17. The criteria against which the options will be assessed are:

- Economic efficiency: A loss company, within a non-wholly owned group that undertakes a loss transfer, should be able to pay a dividend to its shareholders without the single income stream being subject to two layers of taxation. If a profitable company receives the benefit of a loss transfer then distributes part or all of this as a dividend, the shareholder’s tax liability should be equivalent to the tax liability that would have arisen if that profitable company had instead paid income tax and attached imputation credits to the dividend.

- Effectiveness: Because the changes are expected to apply to a relatively narrow subset of taxpayers, the main objective should be achieved with minimal impact on taxpayers who are not transferring losses within non-wholly owned groups.

- Integrity and coherence: The ability to transfer tax-free profits and/or imputation credits both within and outside of wholly-owned and non-wholly owned groups is subject to many areas of existing law. New opportunities should not be created for taxpayers, and particularly those who are not within the problem definition, to transfer profits between entities that are inconsistent with the existing policy intent that the distribution of profits (other than within a wholly-owned group or other specific exceptions) should be subject to tax.

- Efficiency of compliance and administration: The loss grouping and imputation rules are both applied by a wide variety of taxpayers. The complexity of these rules should be minimised to ensure they are applied correctly and with a minimum of compliance and administration costs.

18. While all criteria are not equally weighted all criteria are important. If all of the last three criteria cannot be met to some degree an option that met the economic efficiency criteria would not be preferred.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS

19. Three policy options and the status quo were considered for addressing the policy problem and meeting the main objective. These were:

- Option 1: Retain the current law. This is the status quo option against which the other options are being assessed.

- Option 2: Allow the transfer of imputation credits as part of a loss transfer (preferred option)

- Option 3: Introduce a targeted exemption for dividends following a loss transfer; and

- Option 4: Align the loss transfer and inter-corporate dividend thresholds.

20. There are no environmental, social or cultural impacts for any of the options considered.

Option 1: Retain the current law (status quo)

This option would retain the current law and the existing tax disadvantage for non-wholly owned groups arising from the interaction of the loss grouping and imputation rules.

21. This option would retain the current law and the existing tax disadvantage for non-wholly owned groups arising from the interaction of the loss grouping and imputation rules.

Assessment against criteria – option 1

22. The status quo would not meet the economic efficiency criteria. However, the status quo will not result in any additional compliance or administration costs or create further tax planning opportunities inconsistent with the policy intent so meets the effectiveness, integrity and efficiency of compliance and administration criteria. Therefore, this option is only a valid option if no other option achieves the main objective without creating excessive additional compliance or administration costs or tax planning opportunities.

Option 2: Allow the transfer of imputation credits as part of a loss transfer (preferred option)

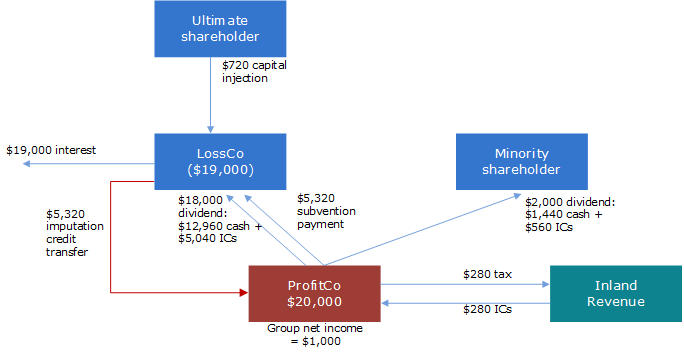

23. Under this option the loss company, or another member of the commonly-owned group, would transfer imputation credits to the profit company as part of the loss transfer arrangement. These imputation credits would allow the profit company to impute the dividend paid to its shareholders.

24. Example 2, which uses the same scenario from example 1, illustrates how option 2 would work.

Example 2

- As part of the $2,800 subvention payment and $7,200 loss offset LossCo also transfers $2,800 of imputation credits.

- ProfitCo still has $10,000 of profit after the loss transfer so pays $2,800 tax. It therefore has $14,400 of cash and $5,600[5] of imputation credits which is the same as if no loss transfer had occurred.

- ProfitCo pays 10% of its profits as a dividend to Minority Shareholder. This is $1,440 cash and $560 of imputation credits. As this dividend is fully imputed Minority Shareholder has to no extra tax to pay.

- ProfitCo pays 90% of its profits as a dividend to LossCo. This is $12,960 cash and $5,040 of imputation credits. As this dividend is fully imputed LossCo has to no extra tax to pay.

- LossCo pays its $10,000 interest bill and distributes its remaining $5,760[6] as a cash dividend with $2,240 of imputation credits attached.

- This can be shown in a diagram as:

25. The consequences of this are that $2,800 of tax has been paid on $10,000 of total income and LossCo is left with no remaining imputation credits.

26. No additional imputation credits are created by this transfer so that the company that transferred the imputation credits would record a debit in its imputation credit account equal to the amount of credits transferred. The majority[7] of the debit from the imputation credit transfer would be matched by a credit from the imputed dividend received from the profit company. This can be shown by considering the imputation credit account entries for LossCo and ProfitCo (Table 1 and Table 2 refer).

| Debit | Credit | Balance | ||

Opening balance |

0 | |||

| Imputation credit transfer | 2,800 | 2,800 | Dr | |

| Dividend received from ProfitCo | 5,040 | 2,240 | Cr | |

| Dividend paid to Ultimate shareholder | 2,240 | 0 | ||

| Debit | Credit | Balance | ||

| Opening balance | 0 | |||

| Tax paid | 2,800 | 2,800 | Cr | |

| Imputation credit transfer | 2,800 | 5,600 | Cr | |

| Dividend to ProfitCo | 5,040 | 560 | Cr | |

| Dividend to Minority shareholder | 560 | 0 | ||

27. In some structures the profit company would pay the dividend to another member of the non-wholly owned group rather than to the loss company. This would arise when the loss company did not own the profit company, for example if the loss company and profit company were both owned by a common parent company. In this instance the taxpayer could manage the imputation debit by transferring the imputation credits from the group member that would receive the dividend rather than the profit company.

28. We acknowledge that this option does not fully achieve the main objective if the loss company receives fewer imputation credits attached to the dividend than they transferred as part of the loss transfer. This can occur when the loss transfer as a proportion of the profit company’s profit is greater than the ownership percentage of the profit company.

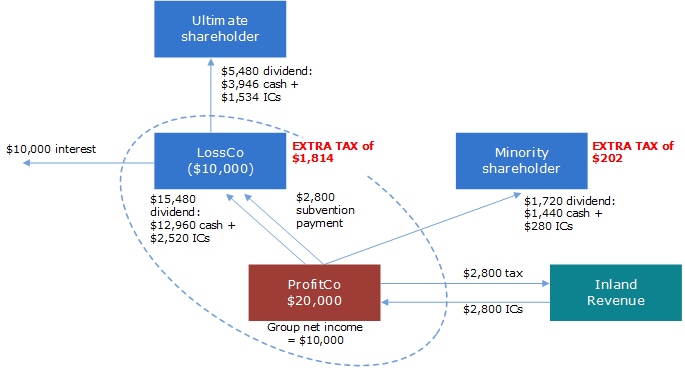

29. Example 3 illustrates this point. It uses the same scenario in Example 2 except LossCo makes a $19,000 loss that is transferred as a $5,320 subvention payment and $13,680 loss offset.

Example 3

- As part of the $5,320 subvention payment and $13,680 loss offset LossCo also transfers $5,320 of imputation credits.

- ProfitCo still has $1,000 of profit after the loss transfer so pays $280 tax. It therefore has $14,400 of cash and $5,600 of imputation credits which is the same as if no loss transfer had occurred.

- ProfitCo pays 10% of its profits as a dividend to Minority Shareholder. This is $1,440 cash and $560 of imputation credits. As this dividend is fully imputed Minority Shareholder has to no extra tax to pay.

- ProfitCo pays 90% of its profits as a dividend to LossCo. This is $12,960 cash and $5,040 of imputation credits. As this dividend is fully imputed LossCo has no extra tax to pay.

- LossCo has $18,000 of income which is fully sheltered by imputation credits so has no income tax to pay.

- LossCo needs $720 additional capital[8] from the Ultimate Shareholder in order to pay its $19,000 interest bill.

- This can be shown in a diagram as:

- However, LossCo started with a nil imputation credit account balance, then transferred $5,320 credits to ProfitCo but only received $5,040 credits on the imputed dividend. LossCo therefore, has an imputation credit account debit balance of $280 so will have to prepay tax. To do this it will need to obtain another $280 capital injection from Ultimate Shareholder.

- Therefore Inland Revenue will collect $560 of tax on only $1,000 of net income. However, LossCo will continue to have tax payments of $280 that could be used to meet a future income tax liability.

30. This concern could be addressed by restricting loss transfers by commonly-owned groups so that the maximum loss transfer was equal to the profit company’s profit multiplied by the loss company’s ownership interest (in example 3 this would be $20,000 x 90% = $18,000). This would result in the loss company transferring less imputation credits but the profit company paying more tax so the same amount of credits could be attached to the dividend. While this would more accurately reflect the commonly-owned group’s share of the profit company’s profit, officials are not recommending this change as it would disadvantage many existing commonly-owned groups. Rather than placing restrictions on the proportion of losses able to be grouped, companies for whom this issue may arise could manage this themselves by choosing to group fewer losses.

Assessment against criteria

31. This option would meet the main objective and the economic efficiency criterion as it removes the tax disadvantage from the interaction from the two sets of rules.

32. This option fully meets the effectiveness criterion as only those companies that are part of a non-wholly owned group that are also grouping losses would be able to transfer imputation credits.

33. This option fully meets the integrity and coherence criterion. This is because the amount of the imputation credits would be capped at the tax value of the loss transfer (in example 3 19,000 x 0.28 = 5,320) and therefore the tax reduction from the payment of an imputed dividend could only be equal to the tax that would have otherwise been paid if the loss transfer had not occurred. While the initial transfer of imputation credits would create an imputation credit account debit, any risk would be mitigated by: requiring the transfer at the same time the dividend is paid; allowing the recipient of the dividend to transfer the credits rather than the loss company; and strengthening the imputation credit shopping rules.

34. Although this option would introduce an extra degree of compliance and administration costs, this complexity is in many cases less than when compared to the other options as the option relies on the existing imputation system which is widely understood. In addition, it is also a voluntary process so taxpayers can quickly calculate whether it would be cost effective to elect into.

Option 3: Introduce a targeted exemption for dividends following a loss transfer

35. Option 3 would operate in a similar way to option 2 as the group would need to identify which dividends were attributable to profits that had been subject to a loss transfer. These dividends would then be non-taxable to their recipient.

36. Option 3 would require a mechanism to track dividends paid and received as all dividends through a chain of companies (including any dividends paid to minority shareholders) would have to retain their tax-exempt status. This mechanism is likely to add considerable complexity to the option. In circumstances where a dividend was partially imputed or where it was partially unimputed for reasons other than the loss transfer, an apportionment mechanism would be required and this apportionment may change as it passes through an ownership chain.

Assessment against criteria

37. Provided the proposed tracking mechanism works correctly this option would achieve the main objective of removing the tax disadvantage. However, owing to the complexity of this option it may not be applied correctly in which case the economic efficiency criteria would not be met. There would be potential for a group to both inadvertently understate the degree of exemption which would result in the tax disadvantage not being fully removed, or of the group to inadvertently or intentionally overstate the degree of exemption which would result in obtaining a tax exemption for income that was outside the scope of the proposal.

38. Similarly, the effectiveness criterion might not be met in all cases due to the complexity of the tracking and apportionment mechanism, which could mean the option is applied too narrowly or too widely.

39. Although there are other provisions of the tax acts that allow for exempt income, this option would be relatively unique in that the exemption would have to flow through a number of companies while not maintaining a distinct character[9]. Provided the proposed tracking mechanism is applied correctly it could help to improve the integrity and coherency of the tax system; but because of the potential for this to be applied incorrectly, the integrity and coherency criterion would not be met.

40. Due to the complexity of the tracking mechanism this option would impose high compliance and administration costs so would not meet the efficiency of compliance of administration criterion.

Option 4: Align the loss transfer and inter-corporate dividend thresholds

41. As noted above, the interaction of the two sets of rules with different thresholds is the underlying cause of this problem.

42. Increasing the threshold for loss transfers to 100 percent would prevent a loss transfer in a non-wholly owned group so that the benefit of this loss transfer could not be clawed back when a dividend was paid as no loss transfer would have occurred. However, this measure would then create an incentive for companies to be wholly-owned in order to group tax losses as well as access the inter-corporate dividend exemption. Therefore, this option would not achieve the main objective.

43. An alternative measure under this option would be to align the loss transfer and inter-corporate dividend thresholds at a lower percentage (presumably the current 66 percent loss transfer threshold). This measure would allow a loss transfer to occur in a non-wholly owned group then the profit company to pay a dividend to its shareholders without that dividend being subject to tax. Within this measure the inter-corporate dividend exemption could apply to either the commonly-owned group only or to all investors in a company that was part of a commonly-owned group.

Assessment against the criteria

44. Applying the inter-corporate dividend exemption only within a commonly-owned group would not be effective as the minority owner of the profit company would still be taxable on their dividend and the profit company would not have sufficient imputation credits to impute this dividend. It would create tax planning opportunities if a company was allowed to stream imputation credits only to its taxable shareholders, and even if this was allowed the profit company still might not have any imputation credits to attach.

45. Applying the inter-corporate dividend exemption to any investor in a company that was part of a commonly-owned group would achieve the main objective of removing the tax impediment for partial ownership. However, it would also make many tax planning opportunities available as profits could be distributed tax-free to any investor in any company provided it was part of a commonly-owned group.

46. The inter-corporate dividend exemption is based on a full consolidation or single economic unit framework. That is, when all companies are owned by the same shareholders, there is no economic difference between their activities being carried on by a single company or multiple companies with the same ownership. This framework does not apply as aptly to 66 percent common ownership. This is because there is a 34 percent difference in economic ownership. Therefore, extending the inter-corporate dividend exemption to commonly-owned companies is inconsistent with the underlying policy of that rule.

47. While this option achieves the main objective and is arguably the least complex there would need to be additional complexity to counter the tax planning activities that would invariably arise. This option would be much wider in scope than the intended audience and would decrease rather than increase the integrity of the tax system.

48. Therefore, this option would either partially or fully meet each of the criteria.

| Option | Main objective and criteria | Fiscal cost/benefits | Costs/risks |

| Option 1 – status quo |

|

|

|

| Option 2 – imputation credit transfer (preferred option) |

|

|

|

| Option 3 – targeted exemption |

|

|

|

| Option 4 – lower inter-corporate dividend threshold • Meets main objective |

|

|

|

Key:

Criterion (a) - Economic efficiency, criterion (b) – effectiveness, criterion (c) – integrity and coherence, criterion (d) – efficiency of compliance and administration

CONSULTATION

49. The preferred option (assessed as option 2 in this RIS) was developed in consultation with the Corporate Taxpayers Group as this issue is particularly relevant to their members.

50. Following development of the preferred option, it was the subject of public consultation in the Loss grouping and imputation credits issues paper, which was released in August 2015. Eight submissions were received on this issues paper. These submissions were generally supportive of the proposal.

51. However, several submitters considered that the preferred option did not fully resolve the issue because the loss company did not receive the full value of the imputation credits via an imputed dividend as a result of the existence of the minority shareholder(s). This shortcoming was particularly evident when the loss company is a sister company of the profit company so does not receive a dividend from the profit company.

52. Officials addressed the sister company concern by amending the proposal to allow imputation credits to be transferred from a group company member that receives the dividend from the profit company.

53. As noted under option 2, the wider issue of the preferred option not fully addressing the claw-back could be removed by restricting the amount of the loss transfer. Officials do not recommend introducing this restriction and prefer to let taxpayers manage this issue by grouping fewer losses if it is in their best interests to do so.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

54. We recommend option 2 be adopted. Option 2 would significantly mitigate the problem identified and would most closely achieve the main objective, while working within existing tax policy settings and using existing rules and mechanisms. By working within the existing rules and not requiring complicated tracking of payments and loss offsets, option 2 would minimise both compliance and administrative costs. Option 3 and 4 would be much more complex to comply with and administer and could also potentially create tax planning opportunities. Although option 2 does not fully achieve the objective in all instances it would provide taxpayers with the ability to manage this risk.

IMPLEMENTATION

55. Changes to the imputation rules to facilitate the preferred option would require amendments to the Income Tax Act 2007 and consequential amendments to other tax legislation. These amendments would be included in a tax bill, scheduled for introduction in March 2016.

56. The preferred option would be taxpayer favourable and would be voluntary for loss transfers occurring after the application of the legislation. Taxpayers would be able to elect to apply the imputation transfer rules after all companies involved in the transfer agreed to participate. Imputation credits would be transferred with the loss transfer but would not be recorded as a debit or credit in the respective imputation credit accounts until the corresponding imputed dividend was paid by the profit company.

57. The imputation credit transfer would be recorded in the respective companies’ imputation credit accounts using existing forms and processes. The companies would be required to keep track of what imputation credits had been elected to be transferred and if the transfer was invalidated[10] before the payment of an imputed dividend the transfer would not be recorded in the imputation credit accounts.

58. Implementing the preferred option will largely require changes to Inland Revenue’s communication and education products. The changes would also require the establishment of an email address for elections so that the use of these rules can be monitored by Inland Revenue. Going forward, Inland Revenue will administer the changes as part of its business as usual processes.

MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

In general, Inland Revenue monitoring, evaluation and review of tax changes would take place under the generic tax policy process (GTPP). The GTPP is a multi-stage policy process that has been used to design tax policy (and subsequently social policy administered by Inland Revenue) in New Zealand since 1995.

Inland Revenue also intends to monitor the operation of the proposed changes via risk review of taxpayers electing to transfer imputation credits to ensure the rules operate as intended.

The final step in the process is the implementation and review stage, which involves post-implementation review of legislation and the identification of remedial issues. Opportunities for external consultation are built into this stage. In practice, any changes identified as necessary following enactment would be added to the tax policy work programme, and proposals would go through the GTPP.

59. In general, Inland Revenue monitoring, evaluation and review of tax changes would take place under the generic tax policy process (GTPP). The GTPP is a multi-stage policy process that has been used to design tax policy (and subsequently social policy administered by Inland Revenue) in New Zealand since 1995.

60. Inland Revenue also intends to monitor the operation of the proposed changes via risk review of taxpayers electing to transfer imputation credits to ensure the rules operate as intended.

61. The final step in the process is the implementation and review stage, which involves post-implementation review of legislation and the identification of remedial issues. Opportunities for external consultation are built into this stage. In practice, any changes identified as necessary following enactment would be added to the tax policy work programme, and proposals would go through the GTPP.

[1] $20,000 less $2,800 subvention payment and $2,800 tax payment.

[2] $2,800 subvention payment plus $12,960 cash dividend less $10,000 interest payment less $1,814 tax payment.

[3] $2,800 paid by ProfitCo plus $202 by Minority Shareholder plus $1,814 by LossCo.

[4] $2,520 from the dividend plus $1,814 from tax paid less $1,534 distributed to Ultimate Shareholder.

[5] $2,800 from tax paid and $2,800 from the imputation credit transfer.

[6] $2,800 subvention payment plus $12,960 cash dividend less $10,000 interest payment.

[7] The exact balance between the imputation credits transferred and those received back on a dividend depend on the amount of the loss transferred as a proportion of the profit company’s profit, the proportionate ownership interest and the proportion of profits paid as a dividend. This is explained further below.

[8] LossCo would also need a further $280 to return its imputation credit account to nil. This is addressed below.

[9] For example a company could have dividends from two sources with one being exempt and one being taxable.

[10] For example by a breach of continuity or where more than four years passed between the loss transfer occurring and the dividend being paid.