GST current issues

AGENCY DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) has been prepared by Inland Revenue.

It provides an analysis of options to address four GST-related items. The issues arise in situations where the technical requirements of the Goods and Services Tax Act 1985 result in high compliance costs for businesses, do not match commercial practice, or do not reach the right policy outcome.

Four items are considered in this RIS. They are:

- The deductibility of GST incurred in raising capital to fund a taxable business activity

- Compliance costs experienced in determining the proportion of GST that can be deducted

- The ability to recover GST embedded in secondhand goods composed of gold

- The treatment of services closely connected with land

A key gap in the analysis of the issues is the information around the size and scale of the items. Information from public sources, provided by submitters, or held by Inland Revenue, has been used to estimate these impacts as far as possible, but in many cases it is incomplete or anecdotal. This has also made it difficult to quantify the impacts.

Submissions received during public consultation on these items and analysis generally agreed with officials’ views on the size and scale of the underlying issue. Submitters included professional firms and industry associations, who may be expected to have a good overview of a number of businesses that may be affected by the proposed regulation.

Where there is not sufficient information to quantify the impacts, this bas been noted in the RIS.

Inland Revenue has consulted the Treasury in relation to all four items. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment was consulted in relation to the capital raising proposal. Both agencies were supportive of officials’ preferred solutions.

The items were also publicly consulted on through an officials’ issues paper, GST Current Issues, released on 17 September 2015. Submitters supported officials preferred solution to the first three items. Submitters did not support officials’ preferred solution for the fourth item relating to the treatment of services closely connected with land. The feedback received has been taken into account in developing options and in the analysis contained in this RIS.

None of the policy options would impose additional costs on businesses, impair private property rights, restrict market competition, reduce the incentives for businesses to innovate and invest, or override fundamental common law principles.

Marie Pallot

Policy Manager, Policy and Strategy

Inland Revenue

11 February 2016

INTRODUCTION

1. This Regulatory Impact Statement considers four GST-related items. Although each item is separate, they all occur within the policy framework of GST and the legislative requirements, found in the Goods and Services Tax Act 1985 (the “GST Act”), that give effect to this policy.

2. These items were the subject of public consultation (in the officials’ issues paper GST Current Issues which was released on 17 September 2015). 14 submissions were received. Most submitters were industry associations or professional firms.

3. The items were:

- To enable businesses to recover GST on costs incurred to raise capital to fund their taxable business activities;

- To address high compliance costs experienced by large, partially exempt, businesses (such as retirement villages) in calculating the GST they can recover;

- To enable businesses acquiring secondhand goods composed of gold, silver or platinum to claim deductions for embedded GST; and

- To amend the tests for when services closely connected with land are treated as consumed in New Zealand, and therefore subject to GST, with the international approach.

4. Analysis of each item follows the following format:

- Status quo and problem definition

- Key objectives for the item

- Regulatory impact analysis – assessment against the stated objectives

- Consultation – how feedback from consultation shaped the analysis of the item

- Conclusion – officials preferred option

GST policy and law

5. Goods and Services Tax (GST) is a tax on consumption. GST is imposed according to the destination principle – that is, that goods and services should be taxed in the jurisdiction in which they are consumed. This results in most supplies of goods and services in New Zealand, as well as imports, being charged with GST. Conversely, exports are not charged with GST.

Consistently with New Zealand’s general tax policy settings, GST is imposed at a single rate (15%), across a broad base of goods and services. This broad-based single-rate approach is intended to distort suppliers’, and purchasers’ preferences as little as possible.

Tax on consumption

6. Although GST is a tax on consumption, it is imposed on all supplies and not just supplies to consumers. To ensure that GST does not accumulate at each step of a supply chain, businesses are able to recover the GST incurred on goods or services they purchase (via “input tax deductions”), where they use those goods and services to make taxable supplies. Input tax deductions are set off against the amount of GST that the business is required to pay on their own supplies of goods and services. If input tax deductions exceed the tax to pay, they are refunded to the business. This “credit-invoice” mechanism ensures that GST is not a cost to business, and is only imposed once on consumption.

7. An exception to this approach exists for some supplies (exempt supplies) which are not taxed when supplied by the business and are instead taxed by preventing the business making the exempt supply from claiming input tax deductions. This option typically will not tax the full value of consumption and is therefore the second-best option from a theoretical point of view. In practice it is used where difficulties valuing the consumption or other practical considerations mean that taxing the consumption is not feasible and input tax deduction denial is the best practical option.

8. Input tax deductions are also allowed for secondhand goods acquired by a business, from a person who does not charge GST on that supply (for example, because they are a consumer). Although the supplier does not charge GST, they will have incurred GST when they purchased the good, which they could not recover. The input tax deduction recognises the consumption of the goods has already been taxed, and that GST is implicitly embedded in the purchase price.

9. In the absence of this rule, secondhand goods could be subject to taxation multiple times – by being taxed when they are first supplied, and taxed again if they are later repurchased and resold by a GST-registered business. The secondhand goods input tax deduction ensures that only additional value added is taxed.

Consumption in New Zealand

10. Another key criterion for goods and services to be taxable is that they be consumed in New Zealand. A number of legislative rules apply to determine whether goods or services are consumed in New Zealand or outside New Zealand. In practice the residency and location of the recipient are used to determine whether services are consumed in New Zealand or not, as well as the nature of the service.

11. Services that are physically performed in New Zealand are generally subject to GST, as they are typically consumed in New Zealand. Under the new place of supply rules proposed in the Taxation (Residential Land Withholding Tax, GST on Online Services, and Student Loans) Bill, GST will also apply to “remote” services (where the supplier and purchaser are not required to be in the same place for the services to be performed) that are performed outside New Zealand, if they are supplied to a New Zealand-resident consumer.

12. In contrast, supplies of services to non-residents outside New Zealand will typically not be taxed. To give effect to this policy of not taxing exported services, the services may be “zero-rated”. The supplier is able to claim input tax deductions for the GST they incur in making the supply, but they will not be required to return GST. This ensures that, for registered businesses, the supply is not taxed, nor is there GST implicitly embedded in the price.

OBJECTIVES

13. The overarching goal is to ensure that GST continues to meet its policy objectives of being a broad-based tax on consumption in New Zealand.

14. The objectives against which the options for each item are to be assessed are:

- Neutrality: Taxation should seek to be neutral and equitable between forms of commerce. Business decisions should be motivated by economic rather than tax considerations. Taxpayers in similar situations carrying out similar transactions should be subject to similar levels of taxation.

- Efficiency: Compliance costs for businesses and administrative costs for the tax authorities should be minimised as far as possible.

- Certainty and simplicity: The tax rules should be clear and simple to understand so that taxpayers can anticipate the tax consequences in advance of a transaction, including knowing when, where, and how the tax is to be accounted.

- Effectiveness and fairness: Taxation should produce the right amount of tax at the right time. The potential for tax evasion and avoidance should be minimised while keeping counteracting measures proportionate to risks involved.

Constraints

15. A key constraint and consideration in meeting these objectives is revenue and, in particular, the policy to tax supplies of goods or services as enshrined in the GST Act. This means that certain minimum compliance and administration costs will be incurred in meeting the obligations imposed under the Act and that most supplies will already be subject to a 15% tax based on their value (with an associated impact on efficiency and neutrality).

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS

16. The four items analysed in this RIS are:

A) The deductibility of GST on costs incurred to raise capital to further a taxable business activity (“Capital raising costs” – page 5 - 10);

B) The compliance costs incurred in applying the legislated approach to determining the amount of input tax deduction that can be claimed in respect of goods and services used to make both taxable and exempt supplies (“Apportionment rules” – page 10 - 17);

C) The ability to claim input tax deductions for secondhand goods composed of gold, silver or platinum (“Secondhand goods and gold” – page 18 - 25); and

D) The treatment of supplies of services that are connected with land (“Services connected with land” – page 25 - 32).

Item A: Capital raising costs

Status quo and problem definition

17. Supplies of financial services are generally exempt supplies. Exempting financial services recognises the inherent difficulty in determining the value of the service, as the financial service provider may be compensated by a margin or spread (for example, on the interest charged for lending) rather than an explicit fee. As it is therefore difficult to determine the value of the financial service consumed, the supply is effectively taxed by denying input tax deductions.

18. There are some exceptions to this approach. Since 1 January 2005, supplies of financial services to GST-registered businesses that predominantly make taxable supplies can be zero-rated, allowing financial service providers to claim deductions for the GST incurred in making these supplies. This was intended to reduce the potential for tax cascades caused by the exempt treatment of financial services, where tax must either be absorbed or passed on by the business receiving the supplies.

19. Another exception is for financial services supplied to non-residents outside New Zealand. The services are zero-rated, as any consumption occurs offshore.

20. Similar concerns arise when businesses that primarily provide taxable goods and services incur costs in raising capital. As the provision of debt or equity securities is treated as an exempt supply of financial services, the GST costs incurred in making these supplies cannot be recovered. Examples of these costs may include NZX listing fees, legal fees and costs associated with preparing a product disclosure statement.

21. As GST is applied on a transactional basis, the ability to claim input tax deductions in respect of goods or services is based on the supplies those goods or services are used to make. As the goods or services are used to make exempt supplies of financial services, deductions are denied.

22. This produces the correct result where the financial services are being consumed by the recipient (for example, the services are consumer lending). However, where the financial services are provided to raise capital, there is a strong argument that these supplies are actually part of the business’ supply chain, and are not consumed by the providers of the capital. Denying deductions for these costs is said to lead to tax cascades, as a taxable business must either absorb the GST cost or pass the cost onto its customers, with GST being charged on this amount again in later stages of the supply chain. This is contrary to GST’s role as a tax on consumption, rather than on business.

23. This analysis does not apply to businesses that principally make supplies of financial services. As these businesses act as intermediaries between borrowers and lenders, it is more difficult to determine the extent borrowing relates to the general business activities and the extent it relates to specific supplies. Special rules exist to enable businesses to elect to zero-rate their business-to-business supplies of financial services. Financial service providers may also enter into an agreement with the Commissioner of Inland Revenue on a fair and reasonable method of apportioning their costs between their taxable and exempt supplies.

24. This analysis is constrained by the available information on capital raising activities. Information on new, publicly listed, equity and debt is published by the NZX. The information published in the annual metrics between 2011 and 2014 indicates approximately $7 billion of new, primary, and secondary and dual equity issued per annum, and $400-500 million of debt.

25. Information on private capital raising is less readily available, both as to the amount of capital raised, and the number of participants in the industry. Industry publications suggest that, in 2014, $200 million of new equity was raised within the venture capital industry. Information on private debt is not available.

Objectives

26. The key objective is effectiveness and fairness. GST is intended to be a tax applied once on consumption only once so that cascades do not occur. This is not the result when capital raising costs are not deductible, and are incurred by the business or passed on. Passing on the cost of this GST may result in a tax cascade, where the unrecoverable GST is embedded in the price paid for the supply, and the supply itself is taxed. Neutrality is also an important objective for this item.

Regulatory impact analysis

27. One policy option and the status quo were considered for addressing the policy problem and meeting the objectives.

- Option 1: Allow a deduction for capital raising costs to the extent that a registered business makes taxable supplies as a proportion of their total supplies.

- Option 2: Retain the status quo under which businesses cannot deduct GST costs incurred in raising capital

Option 1: Allowing a deduction for capital raising costs

28. This option would involve allowing a deduction for GST costs incurred when a registered business raises capital. Amending legislation mechanism would provide for registered businesses that are raising capital in order to fund their taxable activity to calculate an amount that can be deducted.

29. In particular, it would allow a GST-registered business, that does not principally make financial supplies, to claim an input tax deduction for GST costs incurred in the:

- issue or allotment of a debt or equity security;

- renewal or variation of such a security;

- payment of interest, dividends, or an amount of principal in respect of such a security; and

- provision of a guarantee of another person’s obligations under such a security (for example, to guarantee repayment of the principal advanced under a debt security).

30. The GST incurred in relation to these costs would be deductible to the extent that the taxpayer makes taxable supplies, as determined using a method that produces a fair and reasonable result. This method would be consistent with the approach used to determine GST recovery in respect of other goods and services used to make both taxable and exempt supplies. The fairness and reasonableness of the result would need to be determined with regard to the overall business activity to ensure that, as money is fungible, the costs are not allocated in a way to maximise deductions.

31. Currently, there is potentially a tax preference for businesses to source funding in ways that would enable GST to be recovered. Examples include sourcing funds from offshore or, for businesses that have elected to zero-rate their business-to-business supplies of financial services, from a New Zealand business. Providing the ability to deduct capital raising costs that relate to a business’ taxable activity would help address this bias.

32. This option would reduce compliance costs, as registered businesses that only make taxable supplies will not need to identify and apportion the costs that relate both to raising capital and to their other, taxable, business activities.

33. This option also reduces the potential for tax cascades where GST costs are either absorbed by the business or passed on through the supply chain. This improves the effectiveness of GST as a tax on consumption, rather than on registered businesses.

Option 2: Retain the status quo

34. The status quo potentially creates a disincentive to seeking funding from within New Zealand as businesses issuing securities to domestic investors would be unable to deduct their GST costs, whereas those who are exporting financial services can zero-rate these supplies.

35. This option is associated with greater compliance costs for registered businesses that are raising capital, as the costs associated with raising capital need to be determined and treated differently to other inputs acquired by the business to make taxable supplies. This may result in less certainty as the business is required to determine whether the good or service it has acquired is used for raising capital.

The identification of additional practical options to address the objectives was limited, due to the cause of the problem. The problem arises due to a mismatch between the legal and economic frameworks underpinning the GST Act. The question is therefore whether the current legal framework (Option 2) ought to be altered to match the economic framework (Option 1).

Summary of the analysis of the options

36. Option 1 is expected to increase economic efficiency, as it will remove a tax preference for raising capital in ways that maximise GST recovery (for example, from offshore). However, it is not known whether GST recovery is a significant factor in this decision.

37. Compliance costs may be reduced under Option 1. Some costs may relate to both capital raising and other costs, and may arguably be required to be apportioned. Where a business is otherwise wholly taxable, these costs would instead be fully deductible and apportionment would not be required.

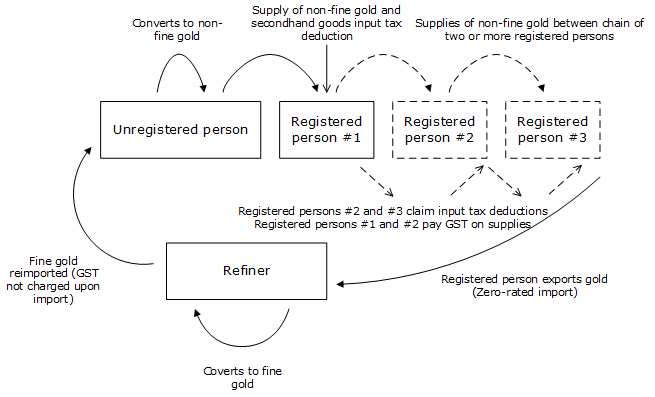

38. Administration costs are not expected to vary significantly between the options, beyond the costs of updating products and communicating changes. Businesses would be expected to apply the rules under either option, and Inland Revenue would monitor compliance.

39. As noted in the problem definition above, there is some uncertainty around the total cost of GST that is not deductible under the status quo, but would be deductible under Option 1. Officials have estimated the total cost of allowing deductions at $10 million per annum, although submitters have indicated that they consider the true cost to be lower, around $3-4 million per annum.

40. Neither option is expected to have social, cultural or environmental impacts.

41. Table 1 summarises the analysis of the options against the stated objectives.

| Neutrality* | Efficiency | Certainty and simplicity | Effectiveness and fairness* | Fiscal impact | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliance costs | Administration costs | |||||

| Option 1: allowing a deduction for capital raising costs | Increased - GST recovery is less influenced by the source of capital. Meets objective |

Decreased - the need to apportion deductions is reduced or the calculation of the deductions simplified. Meets objective |

No change - IRD monitors taxpayers’ compliance with the rules (as with other tax rules). Meets objective |

Increased – fully taxable businesses would not need to apportion costs. Tax obligations are therefore more transparent. Meets objective |

Increased - ensures that final consumption is taxed once. Meets objective |

Decreased – estimated $10 million per annum fiscal cost. |

| Option 2: status quo | No change - incentive to obtain funding in ways that enable GST recovery, such as from overseas. Partially meets objective |

No change - some costs relating to both capital raising and other activities of the business may need to be apportioned. Meets objective |

No change - IRD monitors taxpayers’ compliance with the rules (as with other tax rules). Meets objective |

No change – businesses would need to determine which costs relate to capital raising, and which costs relate to other activities. Meets objective |

No change - denial of deductions leads to GST being imposed multiple times in supply chain. Tax cascade overtaxes the consumption. Does not meet objective |

No change. |

| * = Key objective | ||||||

Consultation

42. Feedback from consultation supported Option 1.

43. Submitters made points about the technical features of Option 1, including the services involved in capital raising and the method that should be used to determine the proportion of input tax that may be deducted, where the funds may relate to both taxable and exempt activities. This feedback has been taken into account in refining these features.

44. Submitters also suggested various application dates, including a retrospective change to enable businesses to claim past deductions. We do not support this suggestion. Policy changes generally apply prospectively, and making an exception in this case could give rise to fairness concerns if the same treatment was not extended in other situations.

45. We note that one submitter submitted on the application of the suggested rules to financial service providers, and supported their exclusion.

Conclusions and recommendations

46. Option 1 is officials’ preferred option on the basis that it best meets the objective. Option 1 better achieves the key objectives of neutrality and effectiveness and fairness. Both options satisfy the other objectives.

Item B: Apportionment rules

Status quo and problem definition

47. A business that makes both taxable and exempt supplies, must apply certain rules to determine the amount of input tax it may deduct. A business that acquires goods or services must estimate the extent to which it expects to use the goods or services to make taxable supplies, as a percentage of total use. The method of determining the use of the goods and services is not prescribed, and the legislation provides for businesses to use a method that produces a fair and reasonable result. This estimated percentage use is the proportion of input tax which the business may deduct in respect of those goods or services.

48. Once a year – and subject to exceptions, including for low-value goods and services – at the end of an “adjustment period” each GST-registered business is required to review the actual use of goods or services it has acquired, and compare it to the estimated use in making taxable supplies. If there is a difference between the estimated use and actual use, the business may be required to make an adjustment – either claiming an additional deduction, or repaying some of a claimed deduction – so that the proportion of input tax deducted accurately matches the actual use of the goods and services in making taxable supplies.

49. Review of the actual use may be required for a number of adjustment periods, subject to rules which reduce compliance costs by only requiring adjustment where the difference between the use and actual use exceeds a certain percentage point amount or the difference in available deduction exceeds $1,000, and by setting out the maximum number of periods for which adjustments need to be made. (For land, there is no maximum number of adjustment periods).

50. While most businesses are required to apply these apportionment and adjustment rules, there are a limited number of exceptions. One exception applies to allow the Commissioner of Inland Revenue and a person who principally supplies financial services to agree an alternative method of calculating deductions. The alternative method must have regard to the tenor of the apportionment and adjustment rules. This recognises the complexity of applying these rules to this industry, and provides a lower compliance-cost alternative.

Problem definition

51. In most cases the apportionment rules are expected to be relatively straightforward to apply, as most businesses can expect to perform a one-off apportionment upon acquisition, with limited further adjustment. However, some business may experience a greater cost in performing these calculations. The key features that are said to give rise to a higher cost include:

- A business activity that includes making both taxable and exempt supplies;

- Use of the same goods and services to make both taxable and exempt supplies;

- A changing proportion of taxable use of the goods or services, or one-off use (in an adjustment period) that does not reflect the long term use;

- A high volume of purchased goods or services; and

- A use of the goods or services which is unknown at the time the goods or services are acquired, or is difficult to determine.

52. Problems also arise due to the need to apportion and adjust the input tax deductions claimed in respect of goods and services, on a supply-by-supply basis. Retirement villages provide an example of these difficulties. The GST treatment of retirement villages, including the treatment of accommodation and the application of the apportionment rules, is discussed in Inland Revenue’s standard practice statement IS 15/02 - Goods and Services Tax - GST and retirement villages.[1]

53. The GST treatment of accommodation depends on the nature of the supply of accommodation. A supply of accommodation in a residential dwelling is exempt, and commercial accommodation is taxable. Many retirement village operators will supply both kinds of accommodation. In some cases, the factor that determines whether a supply is exempt or taxable will be whether, and what kind of, additional goods and services are supplied alongside the accommodation. This may depend on the package of goods and services residents choose, or are required to acquire, alongside the accommodation.

54. This means that it cannot always be possible to accurately determine in advance whether a unit will be used to make taxable or exempt supplies. The actual use will have to be monitored, and adjustments to deductions claimed for goods and services used to construct that unit may be required. This use may also change over time – for example, if residents choose to acquire additional goods and services; or if an existing resident moves to a different unit to receive more intensive care and a new resident acquires the old unit, along with a different package of goods and services. This change in use may also require adjustment of claimed deductions, in respect of specific goods and services, even if the relative taxable/exempt make-up of the entire activity does not change.

55. These difficulties in applying the legislation are understood to also be exacerbated by practical difficulties – in particular, where there is a large volume of goods or services purchased, that must be apportioned and adjusted, and where it is difficult to determine the actual use of the goods and services. An example of the latter is where the goods and services provided are used to construct buildings in which residents will receive accommodation, but it is not clear to what extent the supplies relate to the particular buildings because the invoices do not or cannot provide sufficient detail.

56. The scale of the difficulties experienced by businesses in the retirement village sector is expected to increase as the number of businesses, or the size of businesses, participating in this sector increases. Figures published in the Retirement Village Association’s 2015 Annual Report indicate that there are over three hundred registered retirement villages, with over twenty three thousand units, in New Zealand.

57. Submitters have also indicated that this difficulty may be experienced outside the retirement village industry, by other providers of mixed commercial and residential accommodation. The size of this group is not known.

Objectives

58. The key objectives are efficiency and effectiveness and fairness. However, there may be a trade-off in designing a rule to reduce compliance costs incurred in calculating deductions, while also ensuring that the correct amount of tax is collected at the correct time. Improvements in accuracy of the rule will increase compliance costs for taxpayers.

59. It is more important that the effectiveness and fairness of GST is maintained. Effectiveness and fairness is therefore a more important objective than efficiency.

Regulatory impact analysis

60. The approach preferred by the industry during preliminary consultation was to extend the Commissioner’s ability to agree an alternative method of apportioning, and making subsequent adjustment to, input tax deductions. This gave rise to two alternative options: enabling large, partially exempt, businesses to agree an alternative method with the Commissioner (which is assessed as Option 1); and, following consultation, extending this to also enable industry associations to apply to the Commissioner to agree a method that could be applied across the industry (which is assessed as Option 2).

61. In either approach, an applicant would be expected to apply to the Commissioner to agree an alternative method. The purpose of an agreed method would be to reduce compliance costs by providing an easier way to reach a similar input tax deduction entitlement as would be reached under the apportionment and adjustment rules. To this end, methods would be required to be fair and reasonable, and to have regard to the outcomes that would be reached under the existing apportionment and adjustment rules.

62. An agreed method would be expected to be specially tailored to address the specific difficulties encountered by a business or sector in applying these rules. Therefore, it is not proposed to specify the format or content of a method, however, it is expected that an agreed method would set out:

- all relevant business activities of the applicant;

- the methodology proposed (for example, calculation based on turnover, floor space, time spent, number of transactions or cost allocations);

- categories of costs that can be directly attributed to either taxable or non-taxable supplies, and categories of costs that relate to both taxable and non-taxable supplies;

- the methodology proposed for significant one-off acquisitions such as land;

- the method by which disposals of assets will be dealt with (for example, what input tax adjustments will be made);

- any adjustments that will be made in relation to goods and services that have already been acquired, including those that are subject to the current apportionment rules, transitional rules or old apportionment rules;

- details of any proposed variations to the minimum number of adjustment periods for which adjustments will be made;

- details of any proposed variations to the period in which adjustments will be returned; and

- an explanation of why the proposed methodology is fair and reasonable, and how it reflects the outcomes that would be reached under the apportionment rules.

63. Both Inland Revenue and the applicant are expected to incur costs in agreeing, and maintaining a method. However, it is expected that generally there would be an ongoing compliance cost saving to the customer and a minimal administrative cost for the Commissioner.

Option 1: agreed methods

64. Option 1 would limit eligibility to agree a method to large businesses, which have or expect to have a turnover in a 12-month period exceeding $24 million. In the absence of some kind of threshold, while the Commissioner would not be required to agree a method with every applicant, costs would still be experienced from processing applications and assessing their merits. A turnover threshold would provide an objective test that could easily be applied as a filter, and would limit applications to those expected to be more likely to produce an overall benefit.

65. Businesses would be expected to experience greater certainty under an agreed methodology. It is expected that, for businesses experiencing the compliance difficulties outlined, an agreed alternative method would enable the tax consequences of their transactions to be more readily apparent than under the apportionment rules.

66. It is not expected that an agreed apportionment method would significantly affect the substantive amount of tax paid by a business, and therefore methods should not affect competition between businesses nor the effectiveness and fairness of the tax system, and should not have a fiscal impact. Where a method produced a timing advantage or disadvantage in relation to an input tax deduction (for example, by allowing a flat percentage to be deducted immediately, rather than increasing the amount over a number of years), it is expected that this would be accounted for in the agreement with the Commissioner. For example, a smaller percentage deduction may be allowed to take into account a timing advantage.

67. The use of the turnover threshold under this option to govern applications could potentially create some fairness issues between taxpayers, to the extent that taxpayers who would experience significant compliance cost savings fell beneath the threshold.

Option 2: agreed methods (including industry methods)

68. This option would expand eligibility to agree a method to a wider group of businesses. Industry associations as well as businesses under Option 1 would be able to agree a methodology. Businesses within that industry could then apply to use the agreement with any necessary adjustments as agreed with the Commissioner.

69. Enabling industry associations to also agree a method would be comparatively more efficient, as a single agreement would apply to a number of businesses. The benefit experienced by the entire group could mean that agreeing a method was efficient, taking into account compliance and administration costs, even if the cost of negotiating the method, for an individual member, would not be efficient.

70. This would also help ensure that businesses competing within a sector are on the same footing, and the threshold does not create a benefit of larger size through reduced compliance costs – as all could potentially apply the method.

Option 3: Status quo

71. It would also be possible to maintain the status quo, in which case the situation described in the problem definition would prevail.

Summary of the analysis of the options

72. Option 1 may affect competition between the group of businesses that exceed the threshold and those that do not. Those exceeding the threshold would have an advantage, at the margins, as they would be able to agree an alternative method to reduce the costs of complying with their tax obligations. Option 2 is not expected to produce this same distortion, as where difficulties are experienced by competitors within the same industry, this may be addressed by an industry agreement. Neither option is expected to have an economic impact.

73. Option 1 and Option 2 are expected to reduce compliance costs compared to the status quo. The exact savings are not known.

74. Administration costs under Option 1 and Option 2 are expected to be relatively constant. Some administration costs will be incurred in agreeing a method. The amount of this cost cannot be quantified, as it will depend on the specific circumstances raised, which any alternative method needs to address. Minimal costs are expected to be incurred in monitoring the suitability of an existing method.

75. As the correct treatment of deductions will be easier to determine under a method, it is expected that there will be some administration cost savings in ensuring the compliance of businesses subject to a method. The exact savings cannot be quantified, as it would depend on the specific facts in each instance.

76. None of the options are expected to have social, cultural or environmental impacts.

77. Table 2 summarises the analysis of the options against the stated objectives.

| Neutrality | Efficiency* | Certainty and simplicity | Effectiveness and fairness* | Fiscal impact | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliance costs* | Administration costs | |||||

| Option 1: agreed methods | No change - alternative methods are not expected to disturb the substantive amount of tax payable. Meets objective |

Decreased - costs incurred in agreeing methods. Minimal cost of maintaining a method. Lower cost incurred in applying a method to calculate deductions. Meets objective |

No change - costs incurred in agreeing methods. Minimal cost of maintaining a method. Expected lower costs of ensuring compliance. Meets objective |

Increased - calculation of tax liability expected to be easier as the agreed method can be tailored to the specific difficulties. Meets objective |

No change - methods required to have regard to the outcomes under the apportionment and adjustment rules, to ensure quantity and timing of tax is fair and reasonable. Meets objective |

No change - agreed methods are not expected to alter the amount of deduction that can be claimed. |

| Option 2: agreed methods (including industry methods) | No change - alternative methods are not expected to disturb the substantive amount of tax payable. Meets objective |

Decreased - costs incurred in agreeing methods. Minimal cost of maintaining a method. Lower cost incurred in applying a method to calculate deductions. Meets objective |

No change - costs incurred in agreeing methods. Minimal cost of maintaining a method. Expected lower costs of ensuring compliance. Meets objective |

Increased - calculation of tax liability expected to be easier as the agreed method can be tailored to the specific difficulties, across a broader group. Meets objective |

No change - methods required to have regard to the outcomes under the apportionment and adjustment rules, to ensure quantity and timing of tax is fair and reasonable. Meets objective |

No change - agreed methods are not expected to alter the amount of deduction that can be claimed. |

| Option 3: Status quo | No change - existing apportionment rules determine amount of deductions. Meets objective |

No change - high compliance costs experienced in applying rules. Does not meet objective |

No change - IRD will continue to monitor taxpayers’ compliance with the rules. Meets objective |

No change - calculation of liability may be difficult and complex. Does not meet objective |

No change - existing apportionment and adjustment rules ensure correct tax paid at the correct time. Meets objective |

No change - existing rules would continue to apply to determine the deduction that can be claimed. |

| * = Key objective | ||||||

Consultation

78. Seven submitters supported Option 1, although submissions raised concerns that the suggested $24 million turnover threshold was too high and that it would exclude a number of businesses who experienced high costs in applying the apportionment rules. However, a more appropriate threshold, that would still manage the risk of incurring administration costs from a high volume of applications, was not suggested.

79. Submitters suggested extending the application of the rules to industry associations to extend the ability to agree a method to these groups too. This suggestion is assessed as Option 2 in our analysis.

80. Three submitters suggested that apportionment methods should apply retrospectively to legitimise past approaches. This was considered to increase certainty and be more efficient – submitters were concerned that they may be required to discuss the same issues more than once, for example as part of an audit and in agreeing a method. We do not agree with this suggestion. Allowing a method to be retrospective would increase uncertainty around a business’ obligations in the interim, as it would not be clear whether a business needed to comply with the apportionment rules or if it could instead use a different method (which may be later approved by the Commissioner). Inland Revenue’s internal processes should help minimise duplication of effort and avoid submitters’ efficiency concerns.

Conclusion and recommendation

81. All options meet the objective of neutrality. Agreements with the Commissioner, under Option 1 or Option 2 would not be expected to significantly alter the incidence of tax, from the status quo, but rather be limited to an easier way of reaching a similar figure, so should not affect competition between businesses. Consequently, all options should also result in businesses paying the correct amount of tax at the right time (as agreed methods would be required to take into account the timing of deductions), and there should also be no fiscal impact from any option.

82. Option 1 and Option 2 both satisfy the key objective of efficiency, as the methods agreed between the Commissioner and businesses would reduce compliance costs. Option 2 best satisfies this criterion, as the benefit is extended to a wider group via industry methods. The status quo does not satisfy this objective, as high compliance costs will continue to be incurred in applying the existing rules. All options (including the status quo) are expected to meet this requirement in respect of administration costs. Although entering into an alternative agreement would involve some minor ongoing administration costs, they would produce benefits from making compliance easier to monitor.

83. Both Option 1 and Option 2 would increase certainty for businesses that enter into an agreed method, and the treatment of supplies under an agreed method is expected to be simpler to understand than under the status quo. However, Option 2 applies this to a wider group so therefore better meets this objective. Businesses (in particular, retirement villages) consulted have indicated that they do not find the status quo simple or certain to apply.

84. On balance, Option 2 best meets the objectives, including the key objective of efficiency. Option 2 is therefore officials preferred option.

Item C: Secondhand goods and gold

Status quo and problem definition

85. While input tax deductions are allowed for most secondhand good with few exceptions, one exception is for goods composed of gold, silver, or platinum (collectively referred to as “gold”). The exception applies to the extent that the goods are composed of gold.

86. This exception potentially results in multiple layers of GST accruing on this gold content of secondhand goods. A business acquiring these goods will not be able to claim an input tax deduction; however it may be required to return GST when it supplies the good itself.

87. Alternatively, where secondhand gold is supplied to a refiner who is using it to produce new fine (very high purity) gold, multiple layers of GST should not be incurred (as the fine gold will not be subsequently taxed) but this is the result if the GST is unrecoverable. This outcome is contrary to the policy that fine gold not have embedded GST, and therefore results in taxation contrary to the purpose of the Act.

88. Compliance with the strict rules denying GST deductions results in a number of effects:

- Compliance costs must be incurred in valuing the gold content to determine the extent of permissible deductions;

- Gold goods potentially bear a higher GST burden than other goods, as they are taxed every time they are supplied between a GST-registered business and a consumer, rather than only being taxed on their final consumption;

- Certain methods of transacting, that avoid double taxation, are tax-favoured. For example, there may be an incentive for a secondhand dealer to instead supply an item as an agent for the owner, as only their agent fees will be subject to GST, rather than the full sale price of the item. Alternatively, there is an incentive to sell jewellery privately, thereby avoiding the imposition of additional GST on the gold; and

- Consequently, government revenue is higher, to the extent of the denied deductions. Input tax deductions would offset tax that would otherwise be paid, or paid out as a refund.

89. In practice, these rules are said to be poorly understood, and compliance is said to be low. Most businesses are understood to be claiming input tax deductions for this secondhand gold already. This is said by businesses to distort competition for compliant businesses as businesses that claim deductions can offer a higher purchase price for this secondhand gold because the cost to the business is reduced to the extent a claimed deduction is received.

90. Non-compliant businesses (anecdotally expected to be primarily smaller, less tax-sophisticated, businesses) may be exposed to reassessment by the Commissioner, and to claims for unpaid tax, penalties and interest.

91. Stakeholders have indicated that there are approximately two to three hundred businesses that deal in secondhand gold goods. Many of these businesses are said to have claimed deductions for these goods, based on a lack of understanding of the current obligations. Anecdotally, this lack of understanding is also said to extend to some advisors.

Root cause

92. This situation arises due to a technical exception to the definition of “secondhand goods” in the Goods and Services Tax Act 1985. In particular, deductions are denied for two kinds of secondhand goods that include a gold component:

- Secondhand goods which consist of fine gold, silver or platinum; and

- Secondhand goods which are, or to the extent they are, manufactured from gold silver or platinum.

93. This first exception recognises that the GST policy settings are intended to result in no GST being payable in respect of supplies of fine gold, silver or platinum, and therefore no credit should be available in respect of these goods.

94. As a supply of these metals is not taxed (being exempt, with the first supply of new fine metal being zero-rated) this first exception does not give rise to double taxation concerns – there should be no embedded GST to be recovered.

95. The second exception results from historic concerns about a kind of fraud. As gold may be transmuted between fine and non-fine forms, by combining it with other metal(s), there was a concern this difference in treatment between fine gold and other gold could be abused and used to produce input tax deductions (under the rules for secondhand goods) without any tax having been paid.

96. The specific concern was that untaxed fine gold would be converted to non-fine gold by an unregistered person, and supplied to a registered person who claimed a deduction. The gold would be subsequently supplied between other parties, and eventually exported (as a zero-rated supply) to be refined into a fine form again. (At least two parties were required, as there was, at the time, a prohibition against zero-rating an export, if a secondhand goods input tax deduction had been claimed). Any GST charged as part of this arrangement would be deducted by another party. This is shown diagrammatically on the following page.

97. We note that the conversion between forms must take place by an unregistered person, for this concern to arise, as a registered person carrying on this activity would be required to charge GST when they supplied the gold, in which case GST paid and input tax deductions claimed would net off.

98. This taxation without crediting embedded tax potentially produces two results in respect of the gold content of these goods. Where these goods are on-sold, or are subsequently used to make taxable supplies, the lack of input tax for the value attributable to this gold content potentially results in its double taxation. Alternatively, where these goods are fine gold, which is not taxed itself, the denial of deductions means that it may be effectively taxed, contrary to the policy intention.

Objectives

99. The key objectives are effectiveness and fairness, neutrality, and certainty and simplicity. That is, to ensure that the rules meet the underlying objective that GST applies evenly to the consumption of different goods and services, and that GST distorts competition as little as possible, while providing certainty in a complex area of law.

Regulatory impact analysis

100. Given that the underlying issue is caused by an exception to the framework that is designed to provide for goods to be taxed evenly, both options analysed (aside from the status quo) adopt this as a starting point, with the main difference being the timing of a change, that is, whether or not it should be retrospective.

101. One option is therefore to narrow the exception to the secondhand goods rules, to allow deductions to be claimed for these secondhand goods. Another option is to make the change retrospective, aligned with the time bar for the Commissioner to reassess a return.

Option 1: allowing secondhand goods deductions

102. The exception to the secondhand goods rules for the gold content of any goods could be narrowed. A narrower exception could allow these deductions for goods, such as jewellery, that would pose a lower risk of fraud.

103. Narrowing the exception would help ensure neutrality within business sectors that deal in these goods:

- All businesses would be able to claim deductions in respect of these goods, ensuring that competition takes place upon an even playing field;

- Allowing deductions would remove the tax preference to transact in certain ways, for example, for businesses to add value as agents rather than to purchase and resupply goods themselves, or for consumers to sell items privately.

104. Secondhand gold goods would bear a similar tax burden to other goods. This would have a dual effect of ensuring that GST applies to tax consumption evenly, and collects the right amount of tax at the right time, and would increase neutrality between business sectors, by ensuring that the additional taxation did not distort purchasing or investment decisions.

105. As the current treatment of gold results from an exception to the ordinary rules that apply to secondhand goods, restricting the application of this exception (so that it is not commonly applied and is effectively limited to preventing this fraud) would make the legislation clearer and simpler, and businesses could be more confident that they have applied it correctly. In addition, it is consistent with what we understand to be many businesses’ current practice.

106. However, there may be some remaining uncertainty surrounding businesses’ past compliance. The current legislation is complex and poorly understood, so businesses may not have a high degree of certainty in their past transactions, including the amount of claimed deductions they may technically have to repay, or certainty that they have accurately determined the allowable deduction given that in some cases it may be difficult to precisely value the gold content.

107. Allowing deductions for the gold content of these goods would be expected to reduce compliance costs for compliant businesses. Under this option, these businesses should only incur the ordinary costs of maintaining the required records (which they would currently be expected to do, to claim input tax deductions for the non-gold component of secondhand goods) and would no longer incur cost in apportioning the price paid for the good between the gold content and the non-gold content.

108. Businesses that comply with the secondhand goods rules, but not the exception for gold (that is, they are already claiming these deductions), would be expected to already maintain these records, so this approach would maintain their status quo.

109. No special administration costs are expected to be incurred in administering this option. Costs would be incurred in communicating the changes, updating products and dealing with customer contacts. These costs would not be expected to be significant.

110. Allowing input tax deductions in respect of these goods would reduce the amount of GST collected, as the deductions would reduce GST paid by the business or be refunded. This would reduce GST revenue by a forecast $0.4 million per annum. Persons dealing in these goods would receive a corresponding benefit of $0.4 million per annum.

Option 2: allowing secondhand goods deductions – retrospective (officials preferred option)

111. A variant of the option above would be to apply a change retrospectively, aligned with the time bar for Commissioner reassessments to increase tax payable in a period. This would depart from the above analysis in the following ways:

- It would provide greater certainty to those taxpayers who have previously claimed these deductions, as they would not be required to reassess their past tax positions, and to businesses who have valued the gold content to claim input tax deductions in respect of the non-gold component.

- It would maintain greater fairness and equity between taxpayers. It is possible that non-compliant taxpayers would be reassessed by the Commissioner, and required to repay amounts claimed, use-of-money interest, and penalties. This could have a significant effect on a wide group of businesses given that many businesses are expected to have claimed these deductions. It is arguably not fair for businesses to suffer a significant impact due to a misapplying a complex piece of technical legislation, that is a counter-intuitive exception (for those who are not aware of the underlying policy reason) to the ordinary rules.

- Conversely, compliant businesses should not be disadvantaged by reason of their compliance. Enabling these businesses to recover deductions within this period ensures they are treated equivalently.

112. This option would have a higher fiscal cost, due to the payment of previously unrecovered deductions. This is estimated as an additional one-off cost of $1.6 million.

Option 3: status quo

113. It would be an option to maintain the current treatment. In that case, the situation outlined in the problem definition would continue.

Summary of the analysis of the options

114. Option 1 and Option 2 are expected to increase economic efficiency by removing a tax preference for certain kinds of transactions, and by ensuring all businesses have a similar entitlement to deductions.

115. Option 1 and Option 2 are expected to reduce compliance costs, as businesses will not be required to determine the gold content of secondhand goods, for the purpose of claiming a deduction for the non-gold portion of the goods.

116. Neither option is expected to significantly increase administration costs.

117. None of the options are expected to have social, cultural or environmental impacts.

118. Table 3 summarises the analysis of the options against the stated objectives.

| Neutrality* | Efficiency | Certainty and simplicity* | Effectiveness and fairness* | Fiscal impact | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within sectors | Between sectors | Compliance costs | Administration costs | ||||

| Option 1: Allowing secondhand goods deductions | Increased - value added is taxed – GST is otherwise neutral between businesses and transaction types. Meets objective |

Increased - secondhand gold treated the same as most other secondhand goods. Meets objective |

Decreased - compliance costs comparable to other secondhand goods. Meets objective |

No change - IRD monitors taxpayers’ compliance with the rules (as with other tax rules). Meets objective |

Increased - no special rule for gold. Rules consistent with the rest of the Act. Some uncertainty regarding past positions. Meets objective |

Increased - results in taxation of consumption of gold. Meets objective |

Reduced - revenue decrease estimated at $0.4 million per annum. |

| Option 2: Allowing secondhand goods deductions – retrospective (officials’ preferred option) | Increased - value added is taxed – GST is otherwise neutral between businesses and transaction types. Meets objective |

Increased - secondhand gold treated the same as most other secondhand goods. Meets objective |

Decreased - compliance costs comparable to other secondhand goods. Meets objective |

No change - IRD monitors taxpayers’ compliance with the rules (as with other tax rules). Some returns would need to be reopened. Meets objective |

Increased - no special rule for gold. Rules consistent with the rest of the Act. Past positions preserved. Meets objective |

Increased - results in taxation of consumption of gold. Meets objective |

Reduced - revenue decrease estimated at $0.4 million per annum. One-off cost forecast at $1.6 million. |

| Option 3: Status quo | No change - GST-registered businesses disadvantaged compared to unregistered businesses. Non-compliance distorts competition. Does not meet objective |

No change - secondhand gold treated less favourably than other secondhand goods. Does not meet objective |

No change - compliance costs higher than other secondhand goods as purchaser must determine gold metal content. Does not meet objective |

No change - IRD monitors taxpayers’ compliance with the rules (as with other tax rules). Meets objective |

No change - rules more complex and less consistent, require greater understanding. Some uncertainty regarding past positions. Does not meet objective |

No change - results in taxation upon supply of gold, rather that upon consumption. Does not meet objective |

No change. |

Consultation

119. Four submissions were received on this item, supporting the proposal to make a retrospective amendment (Option 2). Two submitters suggested ensuring that a business that had been reassessed during the retrospective period be able to recover the reassessed amount (even if the particular goods to which the claimed deductions related were purchased outside the four year period). Officials supported this as being consistent with maintaining business’ status quo while ensuring equity between taxpayers. This has been incorporated into Option 2.

Conclusion and recommendation

120. Option 1 and Option 2 both satisfy the key objective that tax be neutral (both within a sector and between sectors) and efficient.

121. It is difficult to determine the relative administration costs of the options – under Option 2, Inland Revenue may incur some costs in reopening a number of returns to pay claimed refunds. However, the cost of the other options will depend on the amount of resources the Commissioner decides to spend on compliance activities.

122. Both options provide similar certainty and simplicity of rules for businesses going forward. Option 2 provides more certainty in respect of past periods, as businesses have certainty about their past affairs. Option 2 is fairer than Option 1, as it ensures that compliant businesses are not disadvantaged by reason of their compliance, while both options ensure that the correct amount of tax (in a policy sense) is collected.

123. On balance, Option 2 best meets the objectives, including being the option that best meets all three key objectives. We therefore recommend this option.

Item D: Services connected with land

Status quo and problem definition

124. Exceptions to the normal rules that tax services based on the location and residence of the recipient exist for services that are closely connected with land. The International VAT/GST Guidelines published by the OECD (the “Guidelines”) recognise that certain supplies, closely connected with real property, may be taxed where that property is located. These services are likely to fall into one of three categories:

- the transfer, sale, lease or the right to use, occupy, enjoy or exploit immovable property,

- supplies of services that are physically provided to the immovable property itself, such as constructing, altering and maintaining the immovable property, or

- other supplies of services and intangibles that do not fall within the first two categories but where there is a very close, clear and obvious link or association with the immovable property.

125. For services to have a sufficiently close connection with land, the Guidelines suggest that the connection with the land must be at the heart of the supply of services and constitute its predominant characteristic,[2] and the associated land must be clearly identifiable.[3]

126. New Zealand to some extent follows this approach of taxing services with a close relationship to the land. The GST Act contains two relevant provisions, which create special treatment for services connected to land:

- Supplies of services to non-residents, located outside New Zealand, (which are generally not taxable) may be taxed where the services are provided “directly in connection” with land in New Zealand (section 11A(1)(k)(i)(A)); and

- Supplies of services “directly in connection” with land outside New Zealand are not taxed (section 11A(1)(e)).

127. The meaning of the “directly in connection with” test, which is used to determine whether certain services with a close connection with land are taxable in New Zealand, has been considered in cases such as Malololailai Interval Holidays New Zealand Ltd v CIR[4] and Wilson & Horton v CIR[5]. The courts have found that a service will not be supplied directly in connection with land when the service merely brings about or facilitates a transaction with a direct effect on land, or when the service could be described as being “one step removed” from such a transaction.

128. A consequence of this interpretation is that a number of services that have a close connection to land may not fall within the scope of these provisions. It is clear that services that have a direct physical effect on land, such as landscaping or construction services, will satisfy the “directly connected with” test under this interpretation. However, it is less clear how the test applies to professional or intellectual services that do not have a direct physical effect on land.

129. Inland Revenue has issued a Public Ruling that legal services provided in respect of land in New Zealand do not meet the test of being supplied “directly in connection with” land, and therefore are zero-rated under section 11A(1)(k) when supplied to offshore non-residents.[6] For example, legal services that facilitate the change of ownership of land, such as the drafting of a sale and purchase agreement, are zero-rated as the service is “one step removed” from the direct transaction between the vendor and the purchaser.

130. Other professional or intellectual services could also fall outside the scope of the specific rule under this interpretation. For example, services provided by an architect could be considered to be “one step removed” from a direct transaction, being the construction of a building. Similarly, services provided by real estate agents in facilitating a change in ownership of land could be “one step removed” from having a direct effect on land.

131. Such a result seems to be inconsistent with the policy intent of the provision. The test was intended to treat services that have a strong connection with land as effectively being consumed where the land is located. It was intended to encompass all services that are closely related to land, rather than to create a distinction between services that have a physical effect on land and those that bring about or facilitate such a transaction.

132. Another consequence of the interpretation is that New Zealand’s specific rule is out of step with international practice, which may lead to double taxation or non-taxation of cross-border services that are connected with land.

133. Equivalent provisions in Australia, Canada and the European Union apply to a broader range of services that are connected with land, as their tests consider whether there is a direct relationship between the purpose or objective of a service and land. In these jurisdictions, legal, architectural and real estate agent services are treated as having a sufficient connection with land where this test is satisfied in relation to a particular property. (However, the Australian Taxation Office considers that, following the interpretation in Malololailai, the services of a real estate agent will not be considered to be directly connected to real property if the agent merely markets the property to willing purchasers.)

134. Double taxation or non-taxation may arise when New Zealand’s specific rule does not capture similar services to those in other jurisdictions. For example, a service provided by a New Zealand lawyer to a New Zealand resident in relation to land outside New Zealand could be taxed in both jurisdictions. Conversely, a service provided by a New Zealand lawyer in relation to the purchase of land in New Zealand may not be taxed in either jurisdiction, if the recipient is a non-resident who is outside New Zealand. In contrast, a resident acquiring the same service, in respect of the same land in New Zealand, would incur GST.

135. The application of the specific rule for services that are received by non-residents is limited by the broad definition of “resident” that applies for GST purposes. Under the GST Act, a “resident” includes a person who carries on a taxable activity or any other activity in New Zealand, while having a fixed or permanent place in New Zealand relating to that activity. This means that services will generally already be taxed in New Zealand when they are supplied to a person who carries on an activity of developing, dividing or dealing in land, or residential or commercial rental of a property in New Zealand. The potentially narrow scope of the specific rule could lead to additional complexity for service providers, as they will need to consider whether their customer is a resident under the expanded definition in order to determine whether each supply should be zero rated.

136. The exact number of businesses providing services that fall outside the scope of the current definition is not known, as we do not have detailed knowledge of the affected industries. However, a number of law firms would be affected, and a number of other professional firms, such as real estate agents or architects may also be affected.

Objectives

137. The key objective is effectiveness and fairness. GST should apply evenly to consumption in New Zealand, and residents and non-residents should be taxed alike. The determining factor for whether GST is charged should be where the goods or services are consumed, rather than who consumes them. GST is not effective and fair when it results in different outcomes for residents and non-residents who are consuming the same services in relation to land in New Zealand.

Regulatory impact analysis

138. One policy option and the status quo were considered for addressing the policy problem and meeting the objectives.

- Option 1: Broaden the scope of the specific rule to apply to services where there is a direct relationship between the purpose or objective of the service and land,

- Option 2: Retain the current GST treatment where the specific rule applies to services which have a direct effect on land, and not to services that could be considered to be “one step removed” from a direct transaction.

139. Note that it is assumed, for the purpose of this analysis, that the policy changes contained in the Taxation (Residential Land Withholding Tax, GST on Online Services, and Student Loans) Bill would be implemented. The Bill would treat cross-border services and intangibles, supplied by non-residents outside New Zealand and received by New Zealand residents, as supplied in New Zealand. Non-residents providing these cross border services and intangibles may therefore be required to register and return GST. The Bill also contains a “tax credit” rule that ensures services provided to non-residents will not be subject to double taxation under both New Zealand’s GST and a foreign equivalent.

140. The identification of additional practical options to address the objectives was limited, due to the cause of the problem. The problem arises due to a mismatch between the legal interpretation of the GST Act and the economic framework underpinning the GST Act. The question is therefore whether the current legal test for where services are consumed (Option 2) ought to be altered to match the economic reality (Option 1).

Option 1: Broadening the scope of the test

141. This option would alter the “directly in connection with land” test, so that it applies to services where there is a direct relationship between the purpose or the objective of the service and land. This would include services that have the purpose or objective of affecting or defining the nature or value of land, protecting land, or affecting the ownership or any interest in land. However, services would not satisfy the test where the part of the service that relates to land is only an incidental aspect of the supply, or if the service does not relate to a designated property.

142. This would mean that services such as those provided by real estate agents, architects and legal services in respect of land in New Zealand would not be zero-rated when supplied to offshore non-residents. Conversely, when these services are provided in respect of land outside New Zealand, they would be zero-rated regardless of the residence of the recipient.

143. Bringing New Zealand’s specific rule for services that are provided in respect of land in line with equivalent rules in other jurisdictions would reduce the potential for double taxation of New Zealand residents’ consumption, and non-taxation of non-residents consumption. This would help ensure that GST taxes consumption effectively and fairly. It would also ensure that residents and non-residents incur the same amount of GST, increasing fairness.

144. In certain cases this option would create a competitive advantage for businesses performing services – connected with land in New Zealand and supplied to non-residents – offshore. These services may not be taxed, including under the new rules for cross-border supplies of services and intangibles. If these services are performed in New Zealand, they may be taxable. This creates an incentive for non-residents to acquire these services from offshore. However, it is not clear to what extent there is in fact competition between New Zealand and offshore suppliers in relation to these services.

145. The opposite applies to services connected with land outside New Zealand and supplied to residents – New Zealand businesses may have a competitive advantage for services supplied to New Zealand residents (depending on overseas rules).

146. Submitters expressed some concern that adopting a new test would reduce certainty, as businesses would need to adapt to the new test and, in contrast the status quo is relatively well understood. It is expected that guidance on the intended application of the rule would be published, to help reduce the uncertainty and to clarify the intended effect of the rule.

147. Submitters were also concerned that the change would potentially increase compliance costs, where businesses making multiple supplies to non-residents would need to distinguish between services connected with land and subject to the new rule, and those that were not. However, other businesses may benefit from the option, as a wider range of services would be subject to more consistent treatment, rather than the GST treatment of a transaction varying based on the residence or location of the recipient.

Option 2: Retain the status quo

148. The status quo results in a narrower range of services being included within the test. In particular, this potentially results in:

- The non-taxation of certain services in relation to land in New Zealand that are consumed in New Zealand by non-residents ;

- The taxation (and potential double taxation) of certain services that are consumed by New Zealand residents outside New Zealand in relation to land outside New Zealand.

Submitters indicated that they considered their obligations under the status quo to be relatively well known. However, submissions were primarily received from industry associations and professional firms – it is not clear if this view is more widely held, particularly as there is no published guidance from Inland Revenue on the application of this test to services, aside from legal services.

Summary of the analysis of the options

149. Option 1 is expected to slightly reduce economic efficiency, as offshore businesses may have an advantage in some cases when providing services to non-residents, in connection with land in New Zealand. It is not clear to what extent there is competition between these resident and non-resident service providers, or to what extent GST influences decisions.

150. Both options are expected to be relatively neutral in relation to compliance costs. Option 1 would change the legal test applied by businesses to determine the GST treatment of their supplies. While there may be some initial uncertainty, this can be reduced by published guidance on the policy intention and intended application of new rules, when they are enacted.

151. Neither option is expected to significantly affect administration costs.

152. Neither option is expected to have social, cultural or environmental impacts.

153. As noted in the problem definition, the exact scale of the impact is not known. Law firms and real estate agencies are expected to be affected by a change. The changes in Option 1 would affect services they provide to non-residents, in respect of land in New Zealand and services they provide to residents, in respect of overseas land. It is uncertain which other businesses will be affected, as it will depend on their specific contractual agreements.

154. Table 4 summarises the analysis of the options against the stated objectives.

| Neutrality | Efficiency | Certainty and simplicity | Effectiveness and fairness* | Fiscal impact | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land in New Zealand | Land outside New Zealand | Compliance costs | Administration costs | ||||

| Option 1: Broadening the scope of the test | Decrease - Supplies to non-residents Meets objective |

No change - Supplies to non-residents Meets objective |

No change - businesses would apply a new test, which is not expected to significantly alter compliance costs from the current test. Meets objective |

No change - IRD monitors taxpayers’ compliance with the rules (as with other tax rules). Cost from updating products and communicating changes. Meets objective |

Decrease - increases uncertainty of business’ obligations. Guidance on intended effect would help mitigate this uncertainty. Meets objective |

Increase - GST applies evenly to consumption in New Zealand. GST does not apply to consumption outside New Zealand. Meets objective |

Increase - revenue increase forecast at $4 million per annum. |

| Option 2: Status quo | No change - Supplies to non-residents Meets objective |

No change - Supplies to non-residents Meets objective |

No change - businesses continue to apply current test. Meets objective |

No change - IRD monitors taxpayers’ compliance with the rules (as with other tax rules). Meets objective |

No change - businesses would apply a longstanding test. Currently little guidance on application to services, other than legal services. Meets objective |

No change - non-residents receive more favourable treatment of some consumption in New Zealand. Residents’ consumption outside New Zealand is taxed. Does not meet objective |

No change. |

| * = Key objective | |||||||

Consultation

155. Submitters were generally opposed to Option 1, with concerns focussing on the uncertainty created by replacing an existing test, which was said to be well understood, with a new one. Officials are aware of this concern, and will seek to clearly set out the policy underlying a change, if one is made, in publicly available material, including the commentary to the relevant amendment bill, and an article in Inland Revenue’s Tax Information Bulletin.

156. Submitters noted that there is currently congruence between the tests for when services provided in connection with land are subject to GST and for when services provided in connection with other goods are subject to GST. Submitters considered that aligning these two tests increases simplicity and consistency of the rules.