Bad debt deductions for holders of debt

Agency Disclosure Statement

This Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) has been prepared by Inland Revenue.

The question addressed in this RIS is whether the tax rules that apply to bad debt deductions for holders of financial arrangements should be changed in order to:

- ensure the tax rules are fair for all taxpayers by allowing them to take bad debt deductions where they would ordinarily be entitled to them on the cessation of the arrangement, but for technical compliance issues; and

- protect the integrity of the revenue base by ensuring that taxpayers can only take bad debt deductions equal to the true economic cost incurred.

Public consultation was targeted at five external parties (including four representative groups and one tax advisor). These parties were consulted because they either have a strong interest in general tax policy amendments, or an interest in the particular issues. All feedback received supported the proposals for change. Several comments were also made on technical matters (such as the scope of the compliance costs change). The proposed legislative draft has been amended where appropriate.

Two specific changes to the tax rules applying to bad debt deductions are recommended. The first change makes the tax rules fairer and reduces compliance costs. This is a taxpayer-friendly change that will make it easier for holders of debt to take deductions in circumstances where they ordinarily should be entitled to them but for technical compliance issues. The second change is a base maintenance measure to ensure that holders of financial arrangements cannot take excessive bad debt deductions. This change aligns the tax rules with the existing policy intent of the bad debt rules and protects the integrity of the revenue base.

We propose that the recommended base maintenance change applies from when the tax bill containing the changes is introduced. This change will be subject to a retrospective claw-back rule that will require taxpayers who have taken excess deductions (that is, deductions for more than the economic cost), to return those amounts as income in the 2014–15 year. The effect of this rule is that the change will be retrospective for financial arrangements that are in existence in the 2014–15 year, but any tax payable will be prospective. This rule is necessary to protect the revenue base.

The Treasury has been consulted and agrees with the contents of this statement.

There are no key gaps or dependencies, assumptions, significant constraints, caveats or uncertainties concerning the analysis.

None of the policy options considered impair private property rights, restrict market competition, impose additional compliance costs, or override fundamental common law principles.

Joanna Clifford

Programme Manager, Policy

Inland Revenue

12 March 2013

STATUS QUO AND PROBLEM DEFINITION

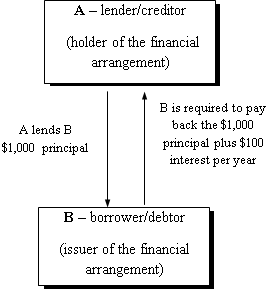

1. A financial arrangement is an arrangement under which a person receives money in consideration for providing money to any person at a future time, or on the occurrence or non-occurrence of a future event. A simple example is shown below:

2. In some situations, the original creditor/holder of the financial arrangement (A) can transfer the financial arrangement to a new creditor/holder (referred to as a “subsequent holder” in this RIS). In these situations, the debtor (B) is required to pay the outstanding interest and principal amounts to the subsequent holder.

3. The financial arrangement rules are separate from the rules for bad debt deductions. A bad debt is a debt where there is no reasonable likelihood that it will be received. In certain circumstances, the bad debt rules allow the creditor (either A or a subsequent holder), to take a deduction for a bad debt where that debt has been written off as bad during the same income year.

4. There is a required process for writing off bad debts arising from financial arrangements. Bad debts for amounts owing under a financial arrangement must be written off before the financial arrangement ends (for instance, by liquidation). This means that if a taxpayer fails to take a bad debt deduction before that time, a bad debt deduction cannot later be taken.

5. The bad debt write-off rules ensure that taxpayers are not taxed on amounts which may have been derived and included as assessable income, but are never actually received. If deductions for bad debts were not allowed, taxpayers would pay too much income tax because they would be assessed on income which substantively was not received.

6. The questions addressed in this RIS are whether the tax rules that apply to bad debt deductions for holders of financial arrangements should be changed in order to:

- ensure the tax rules are fair for all taxpayers by allowing them to take bad debt deductions where they would ordinarily be entitled to them on the cessation of the arrangement, but for technical compliance issues; and

- protect the integrity of the revenue base by ensuring that taxpayers can only take bad debt deductions equal to the true economic cost incurred.

Issue 1: Compliance

7. The first issue with the current tax rules is that the strict technical criteria for taking a bad debt deduction are unnecessarily onerous. This gives rise to unfair results and high compliance costs for certain creditors.

8. Currently, the tax rules require that where a borrower (debtor) goes into liquidation or bankruptcy, the creditor can take a bad debt deduction only if the debt was written off as bad in the same income year, and before the liquidation or bankruptcy took place. This requirement can be unnecessarily onerous for certain creditors (particularly small “mum and dad” investors in failed finance companies), as it means they would need to have up-to-date knowledge of the financial state of the debtor in order to take bad debt deduction in time. In some situations, creditors are not informed of upcoming liquidations or bankruptcies and this means they would need to regularly check the companies register or public listings for updates on the financial stability of debtors.

9. The same strict write-off criteria apply to creditors where the debtor company has entered into a composition with them (for example, where the creditor agrees to accept 70 cents for every dollar owed by the debtor). In these cases, the creditor can take a bad debt deduction only if the debt was written off as bad in the same income year and before the composition took place. Again, the write-off requirement can be unnecessarily onerous for creditors because the timeframe to write off the debt can be short (the period between being informed of the financial difficulties of the debtor and the composition itself).

10. Creditors who fail to write off the bad debt in time (before the debtor is liquidated/bankrupted, or before a debtor company enters into a composition with creditors), will have a tax obligation in respect of accrual income they have never received, or remission income that was never written off. This result is unfair and leads to unnecessarily high compliance costs.

11. Following the recent financial crisis, we have become aware that some investors in failed finance companies have not always met the required criteria of writing off the bad debt before the finance company (debtor) was liquidated or entered into a composition with its creditors. Theoretically, these taxpayers would have been denied a bad debt deduction they would ordinarily have been entitled to claim. Therefore, in theory, these taxpayers would be adversely impacted if no legislative action is taken. We are unable to quantify the magnitude of this impact because we do not know who exactly is affected.

12. When the bad debt deduction rules came into force, the likelihood of some creditors (including creditors of liquidated companies and bankrupt individuals) being unable to meet the “write off” requirement and the implications of this were not fully identified.

Issue 2: Base maintenance

13. The second issue with the current tax rules is that holders of debt can take bad debt deductions for amounts owing even where the holder has not suffered an economic loss. This result is not in line with existing policy for bad debt deductions. It also results in an unjustified timing advantage and presents a risk to the integrity of revenue base.

14. For example, it is possible for taxpayers to legitimately carry out a business of buying debts in an attempt to recover as much of the amount owing as possible, and thereby make a profit. Currently, these taxpayers would be able to take a deduction for the amount legally owing under the debt even though the (smaller) amount they paid for the debt reflected the fact that the entire amount was unlikely to be received. These taxpayers are required to return income when the base price adjustment (wash-up calculation) is performed at the end of the financial arrangement. However, we are concerned that taxpayers are able to take bad debt deductions earlier than they should, because it gives them an unjustified timing advantage. To protect the tax base, these inappropriate deductions should not be able to be taken.

15. We are aware of one taxpayer who is currently operating in this area and, under the status quo, there is a risk that other taxpayers will take excess bad debt deductions.

OBJECTIVES

16. The objectives are to:

- ensure the tax rules are fair for all taxpayers by allowing them to take bad debt deductions where they would ordinarily be entitled to them and

- protect the integrity of the revenue base by ensuring taxpayers can only take bad debt deductions equal to the true economic cost incurred.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS

17. To achieve the objectives outlined above, a number of options were considered.

Issue 1: Compliance

18. The first issue being considered is that, in some situations, the current strict technical requirements for taking a bad debt deduction are unnecessarily onerous and this gives rise to unfair results (whereby taxpayers are treated as receiving income which was never received). Three options were considered for addressing this issue and these are set out below.

| Options | Does it meet the objectives? | Impacts | Risks | Net impact | ||||

| Compliance | Economic | Social | Costs | Environmental and cultural | ||||

1A Amend the current write-off criteria in the bad debt deduction rules to enable taxpayers to take a bad debt deduction where:

(recommended option) |

Yes | Minimises compliance costs – no need for taxpayers to regularly check the companies register or public listings for updates on the financial stability of the debtor. Increases certainty of tax treatment for taxpayers. |

None | Fairness – easier for taxpayers to take deductions for economic losses which, under current policy settings, they are entitled to. In particular, it reduces compliance costs for “mum and dad” investors who are less likely to have thorough knowledge of their accounting and tax obligations. The overall result means the taxpayers are not assessed on income which was never received. |

Fiscally negative, but the fiscal effect is not expected to be large. No material fiscal effect on baselines. We are not in a position to estimate the precise fiscal effect because we do not know exactly how many creditors would be affected. No significant administrative implications. |

None | The amendment is not limited to bad debt deductions arising under financial arrangements – it extends to all bad debts. This could result in unintended impacts on other arrangements (for instance, if it becomes too easy to take deductions where the debt is not truly a bad debt). |

Overall, positive. This option improves the status quo because the positive impacts (compliance, economic and social) outweigh the risks. Although there is a theoretical risk that the extended ability to take deductions may span too wide, officials have not identified any situations where this would, realistically, be outside the policy intention |

1B Two new special deductions introduced (base price adjustment deduction and accrual income deduction). Together, these deductions would ensure that where income is required to be returned for tax purposes, a deduction would be allowed for these amounts if the income amounts were never received. |

Yes | Minimises compliance costs – no need for taxpayers to regularly check the companies register or public listings for updates on the financial stability of the debtor. Increases certainty of tax treatment for taxpayers. |

None | Fairness – easier for taxpayers to take deductions for economic losses which, under current policy settings, they are entitled to. In particular, compliance costs are reduced for “mum and dad” investors who are less likely to have thorough knowledge of their accounting and tax obligations. Overall, taxpayers are not assessed on income which was never received. | Fiscally negative, but the fiscal effect is not expected to be large. No material fiscal effect on baselines. We are not in a position to estimate the precise fiscal effect because we do not know exactly how many creditors would be affected. No significant administrative implications. |

None | New deduction provisions will make the legislation more complicated. Given the complexity of the relationship between the current financial arrangement rules and bad debt rules, additional complexity is not desirable. | Overall, neutral. While the ability for taxpayers to take automatic deductions where appropriate is positive from a policy perspective, the risk of unnecessarily complicating the financial arrangement tax rules is considered undesirable. |

1C Retain the status quo. Require holders of debt to meet the current criteria so that the debt must be written off as bad before the debt is remitted, and in the same year that the deduction is sought. |

No | Does not require legislative change. Feedback suggests taxpayers are not complying with the current strict technical requirements, but are already taking deductions considered appropriately deductible from a policy perspective. | None (other than fairness and compliance). | Fairness – arguably unfair if a bad debt that would ordinarily be deductible is not deductible simply because the write-off criteria were not met in time. If Inland Revenue allows taxpayers to take deductions which are not allowed under current legislation, this could be perceived as unfair. |

None | None | The current law requires certain compliance criteria to be met. If the criteria are not amended, there will continue to be uncertainty for taxpayers. | Overall, negative. The objectives are not met. While it is arguable that legislative change is not necessary because taxpayers are already taking deductions (in line with the policy intent), the strict technical requirements that should legally be met, and the uncertainty around the current law, is considered real and significant. |

Issue 2: Base maintenance

19. The second issue being considered is that holders of debt can take bad debt deductions for amounts owing even where the holder has not suffered an economic loss. This result is inconsistent with existing policy settings. Three options were considered for addressing this issue:

| Options | Does it meet the objectives? | Impacts | Risks | Net impact | ||||

| Compliance | Economic | Social | Costs | Environmental and cultural | ||||

2A Amend the bad debt deduction tax rules by limiting the deductions that can be taken to the economic loss (amount lent or amount paid to purchase the debt). The current base price adjustment and bad debt deduction rules will continue to work as intended to square up any losses/gains overall. Introduce an anti-avoidance measure to limit the deductions being taken to the real money at risk. (recommended option) |

Yes | None. | Revenue integrity is maintained because excess deductions are stopped. Coherence – aligns with the tax system as a whole. Efficiency and growth – Limiting the deductions that can be taken may reduce the incentive for businesses to innovate and invest, since the status quo provides an unintended advantage in the form of excessive and unjustified tax deductions. Increases certainty for taxpayers. |

Fairness – Addresses the timing advantage that can be obtained under the current bad debt and financial arrangement rules. | Fiscally positive, but insignificant, because it is believed that the majority of taxpayers are correctly applying the law as intended by policy. We are not in a position to estimate the precise fiscal effect because we do not know exactly how many creditors would be affected. There is no material fiscal effect on baselines. No significant administrative implications. | None. | None. | Overall, positive. Option 2A would be an improvement on the status quo and meets the objectives. As noted, option 2A may reduce the incentive for businesses to innovate and invest, however officials consider this is justified because removing this advantage simply aligns the law with the existing policy intent. |

2B Disallow excess bad debt deductions and amend the base price adjustment formula in the financial arrangement tax rules so that the creditor’s base price adjustment result does not include the amount remitted by law. The anti-avoidance measure would limit the deductions being taken to the real money at risk. |

Yes | Compliance costs would increase. The financial arrangement tax rules are already complicated, and amending them may make them harder to comply with. | Coherence – aligns with the tax system as a whole. Efficiency and growth – Limiting the deductions that can be taken may reduce the incentive for businesses to innovate and invest, since the status quo provides an unintended advantage in the form of excessive and unjustified tax deductions. Maintains revenue integrity. |

Fairness – Addresses the timing advantage that can be obtained under the current bad debt and financial arrangement rules. Increases certainty for taxpayers. |

Fiscally positive, but insignificant, because it is believed that the majority of taxpayers are correctly applying the law as intended by policy. We are not in a position to estimate the precise fiscal effect because we do not know exactly how many creditors would be affected. There is no material fiscal effect on baselines. |

None. | The (complex) financial arrangements rules generally work well. Amending these rules would add complexity to these rules which may unintention-ally affect other arrangements. | Overall, neutral. This option is an improvement on the status quo and the objectives are met. However, the complexity of amending the financial arrangement rules is considered a real and significant risk. |

2C Retain the status quo The current legislation is unclear, but it may be possible for bad debt deductions to be taken for more than the cash or economic loss incurred to obtain the debt. |

No | None. | Efficiency – If excess deductions can be taken, this could distort behaviour (by providing incentives to invest in financial arrangements rather than other forms of investment), which is inefficient. |

Fairness – if taxpayers take advantage of the unclear legislation by taking deductions for excess amounts, this would be viewed as unfair, because the deductions are not justified. |

There is a risk that if a base maintenance change is not made, and taxpayers take deductions for more than their economic loss, this could result in a potentially significant, fiscal loss and a risk to the revenue base. We are not in a position to estimate the precise fiscal effect because we do not know exactly how many creditors would be affected. |

None. | Revenue integrity – if no legislative change is made, there is a risk to the tax base because taxpayers may take deductions that are not justified. |

Overall, negative. This option is not an improvement on the status quo and the objectives are not met. It can be argued that legislative change is not required because the majority of taxpayers are already interpreting the legislation purposively, in line with the policy intent. However, this is a base maintenance measure, and if legislative change is not made, there is a potential risk to the revenue base, potentially distortions in behaviour and perceived unfairness. |

Application dates

Compliance change

20. We recommend the change which addresses the compliance issue applies from the 2008–09 year. The application date should be retrospective for reasons of fairness, so that investors are not assessed on income which was never received. Taxpayers who will benefit from this change are most likely to be investors in failed finance companies (“mum and dad” investors). The proposed change needs to be retrospective to enable investors to take bad debt deductions for amounts owed following, for example, a finance company going into liquidation or entering into compositions with creditors, otherwise investors would be faced with a tax liability even if they have not received any income. The 2008–09 year was selected on the basis that it would be sufficient to assist affected taxpayers.

Base maintenance change

21. We also recommend that the base maintenance change applies from when the tax bill containing the proposed changes is introduced, and that there be a retrospective claw-back rule to require taxpayers who have taken excess deductions (that is, deductions exceeding the cost of acquisition and any income returned), to return those amounts as income in the 2014–15 year. The effect of the claw-back rule is that the rule is retrospective for financial arrangements that are in existence in the 2014–15 year, and affected taxpayers must return extra income prospectively (in the 2014–15 year). We consider that this is justified because it puts them back in the same position they should be in, in line with the policy intent. There is no concern with financial arrangements that have ended prior to the 2014–15 year, as the base price adjustment (wash-up calculation) that would have been performed should have squared-up any excess deductions taken.

22. The benefit that taxpayers get under the current rules is a timing advantage. If the claw-back rule did not apply, the correct result would be reached when the base price adjustment (wash-up calculation) is performed at the end of the arrangement. However, it is possible for taxpayers to drag out financial arrangements so that a base price adjustment is performed much later than appropriate. This application date ensures that when taxpayers have inappropriately taken excess deductions, unknown to Inland Revenue, the advantage obtained for any existing financial arrangements is reversed by requiring the excess amounts to be returned as income. It is also recommended that a savings provisions apply for taxpayers who are, at the date of introduction of the tax bill, involved in assessments subject to the tax disputes process.

CONSULTATION

23. In September 2012, targeted consultation was undertaken with five external parties; four representative organisations and an external tax advisor. We consulted with these parties because they either have a strong interest in general tax policy amendments, or have an interest in the particular issues.

24. Four of the consulted parties provided feedback, and all four supported the options 1A and 2A.

25. Three parties provided feedback on the application dates of the proposed legislative changes. All three submitted that the compliance change should apply on a retrospective basis, and the base maintenance change should apply on a prospective basis. These submissions were partially accepted, as described below:

- For pragmatic reasons, the compliance costs change is retrospective only to the 2008–09 year.

- The base maintenance change will apply prospectively, but also claw-back excess deductions that have been taken. The effect of the claw back is that the base maintenance rule is retrospective for relevant financial arrangements that are in existence in the 2014–15 year, but any tax payable is prospective. It is not anticipated that a large number of taxpayers will be affected by the claw-back rule; however, it is necessary for base maintenance reasons. The reason for the claw-back rule is that, notwithstanding the current legislative wording, it is not considered reasonable for taxpayers to take deductions for more than their economic loss under the financial arrangement. There will be a savings provision for taxpayers who are involved in assessments that are subject to the disputes process. This will mean that, as at the introduction date of the bill, disputes will continue as per the regular process and will not be subject to the retrospective claw back of excess deductions. The claw-back rule will still apply to excess deductions taken by taxpayers who are not in the disputes process at the date the tax bill is introduced.

26. Three parties provided feedback on the technical detail of the proposed changes. The technical matters raised are discussed below.

| Consulted party | Technical comments raised by submitters | Proposed response to technical comments raised |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Technical change 1: Extend situations where compliance costs change should apply (for Insolvency Act and other jurisdictions). The compliance costs change should extend, not only to debts remitted by law under the Companies Act 1993, but also to debts remitted by law under the Insolvency Act 2006, or the laws of a country or territory other than New Zealand. It appears that the submitters have requested these additional operations of law to reflect the wording of the provision in the financial arrangement rules that deals with debts remitted by law. | This technical change was accepted and the draft legislation will be amended to meet this result. Officials considered it appropriate to align the wording in the two sets of provisions even though they did not consider the change strictly necessary (as creditors of bankrupt individuals should be able to meet the current bad debt criteria). |

| 2 | Technical change 2: The compliance costs change should extend to situations where the debt has been remitted when the debtor company is released from making all remaining payments by a deed or agreement of composition with the creditors in the income year (for example, where the creditor agrees to accept 70 cents for every dollar owed). | This technical change was accepted and the draft legislation will be amended to meet this result. Officials agreed that, in certain situations where there has been a composition with creditors, an automatic bad debt deduction should be allowed. |

| 3 | Technical change 1, described above.Technical change 3: For tax purposes, capitalised interest (interest which has been added to the original capital), should be separated into interest and principal. | This technical change was accepted and the draft legislation will be amended to meet this result.Technical change 3 was not accepted. Inland Revenue has a longstanding practice of treating capitalised interest as being paid to the investor and reinvested. Officials do not consider it appropriate to change this practice because capitalised interest is a close substitute for an investor receiving interest and then reinvesting it themselves. If the tax treatment of capitalised interest was amended this would treat similar transactions differently, which would be inequitable. Further, there would be a fiscal cost in doing so. |

| 4 | No technical comments raised. | Noted |

| 5 | No feedback received. |

27. As part of accepting technical change 1, a related change should be made for the use of losses after bankruptcy to correct a previous oversight in the tax rules. Currently, when a debtor is released from a financial arrangement debt on discharge from bankruptcy, they can use the losses arising from the financial arrangement debt to offset post-bankruptcy income. From a policy perspective, the debtor should not be entitled to use pre-bankruptcy losses to offset post-bankruptcy income. This correct policy result is the rule that applies to non-financial arrangement debt remitted on discharge from bankruptcy, and the rule for financial arrangement debt should align with this.

28. The Treasury has been consulted in the policy proposals and the preparation of this RIS, and agrees with its contents.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

29. The recommended options to address the two issues are 1A and 2A. These options involve:

- Amending the current strict technical requirements in the bad debt deduction rules to enable taxpayers to more easily take a bad debt deduction where the debt has been remitted by law, such as by liquidation or bankruptcy; or where the debtor company entered into a composition with creditors. This will remove the strict technical compliance requirements in certain cases and thereby make the tax rules fairer

and

- Amending the bad debt deduction tax rules by limiting the deductions that can be taken to the economic loss (subject to an anti-avoidance measure to limit the deductions being taken to the real money at risk). This will protect the integrity of the revenue base by ensuring taxpayers can only take bad debt deductions equal to the true economic cost incurred.

30. Both options meet the objectives and are an improvement on the status quo because the positive impacts identified are considered to outweigh the risks.

IMPLEMENTATION

31. No implementation risks have been identified. We consider that implementation can be managed within existing systems and there would be no other significant administrative issues. The changes will be communicated by updating Inland Revenue publications, and advising Inland Revenue staff, tax agents, large enterprises and businesses of the changes. A Tax Information Bulletin item will be published when the legislation is passed. This will fully explain the new rules for taxpayers.

32. Enforcement of the proposed changes will be managed by Inland Revenue as business as usual and there will be no specific enforcement strategy required. There are no transitional arrangements required. It is proposed that any legislative change would be included in the tax bill expected to be introduced in April 2013.

MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

33. There are no plans to monitor, evaluate and review the changes after they become law. This is because the reforms align the current rules with existing policy and the approach generally adopted in practice. If any specific concerns are raised, officials will determine whether there are substantive grounds for review under the Generic Tax Policy Process. Also, the Income Tax Act 2007 is subject to regular review by officials. As per the normal process, there will be an opportunity for submissions to be made on the proposed changes during the select committee stage of the tax bill that any legislative change is contained in.