Special report on the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2020–21, Feasibility Expenditure, and Remedial Matters) Act 2021

April 2021

Purchase price allocation

This special report explains the new purchase price allocation rules in sections GC 20 and GC 21 of the Income Tax Act 2007 (the Act), inserted by the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2020–21, Feasibility Expenditure, and Remedial Matters) Act. The rules reinforce and extend existing provisions requiring parties to a sale of business assets with different tax treatments to adopt the same allocation of the total purchase price to the various classes of assets for tax purposes.

Background

Sales of business assets are often subject to more than one tax treatment. These sales are sometimes referred to as ‘mixed supplies’. For example, a sale of commercial property will normally include depreciable buildings and fitout, and land held on capital account (non-taxable/non-deductible). The vendor and purchaser will agree a total price for the transaction, but may or may not allocate the price between the different assets. For tax purposes, however, the parties are usually required to make an allocation, to determine the vendor’s tax liability and the purchaser’s basis for deductions. This is referred to as a ‘purchase price allocation’.

Allocations must reflect market values for the various assets, but market value is a range rather than a single figure. Current law requires a purchaser of trading stock in a mixed supply to treat the trading stock as acquired for the same value as the vendor treats it as sold for (section EB 24(3) of the Act). Trading stock for the purposes of section EB 24 is broadly defined, to include livestock, land held on revenue account, and timber. Section DP 10(1) reinforces this rule for timber. However, these rules do not contain a mechanism for the vendor’s allocation to be communicated to the purchaser, if the allocation is not stated in an agreement. Also, there is no explicit consistency requirement for depreciable property or financial arrangements. As a result, under prior law there were many cases where the vendor and the purchaser in mixed supplies ascribed different market values to the same assets often with the effect that their aggregate reported income was lower than if they had applied consistent valuations.

Example 26

Shark Attack Commercial Limited (Shark) is a commercial property owner with a number of buildings in the Auckland CBD. It wishes to sell one of its prime buildings, the Waiata Centre, to Corroboree Properties Limited another commercial lessor. The assets being sold comprise the land, building and fitout of the Waiata Centre. Shark and Corroboree agree on a purchase price of $150 million but they do not allocate that purchase price between the land, building and fitout.

When Shark files its tax return it allocates the purchase price as follows:

| Item | Amount |

| Land | $100m |

| Building | $40m |

| Fitout | $10m |

| Total | $150m |

However, Corroboree obtains a valuation of the building and applies that valuation to determine the values in its tax return:

| Item | Amount |

| Land | $80m |

| Building | $50m |

| Fitout | $20m |

| Total | $150m |

This results in a tax mis-match between the two taxpayers over the same assets giving Corroboree a higher tax depreciation base than the amount returned by Shark in determining its depreciation recapture income.

The purchase price allocation rules address this lack of consistency and of information, applying to agreements for the disposal and acquisition of property entered into on or after 1 July 2021. An agreement is entered into once it is binding on the parties, whether or not there are conditions (for example, a standard finance condition for the benefit of the purchaser) that remain to be met and which if not met will mean the transaction does not proceed.

Key features

- Purchase price allocations are to be made at the level of the following classes of ‘purchased property’:

i) trading stock, other than timber or a right to take timber

ii) timber or a right to take timber

iii) depreciable property, other than buildings

iv) buildings that are depreciable property

v) financial arrangements, and

vi) purchased property for which the disposal does not give rise to assessable income for person A (the vendor) or deductions for person B (the purchaser).

Agreed allocations

- If the parties agree an allocation to the classes of purchased property and record it in a document before the first tax return for the year in which the transaction occurs is filed, they must both follow that allocation in their returns. This agreed allocation over-rides any prior unilateral allocation that may have been made (see below).

Unilateral allocations meeting timeframes

- If the parties do not agree an allocation and record it in a document before the first tax return for the transaction is filed, the allocation will be determined by a notification made by one of the parties, or the Commissioner. However, a unilateral allocation does not need to be notified if the total consideration for the purchased property is less than:

a) $1 million, or

b) $7.5 million, if the only purchased property is residential land (which includes residential buildings) together with its chattels.

- The vendor has three months after the change in ownership of the property to notify an allocation to the purchaser and the Commissioner, which then binds the vendor and the purchaser.

- If the vendor does not notify an allocation within three months, the purchaser has three months (that is, until six months after the change in ownership) to notify an allocation to the vendor and Commissioner, which then binds the purchaser and the vendor.

No unilateral allocation meeting timeframes

- Where the parties have not agreed an allocation, and neither party notifies a unilateral allocation (filing of a return containing an allocation is not notification of an allocation):

- the Commissioner may determine the allocation,

- the purchaser is not entitled to any deductions for the purchased property until the Commissioner notifies an allocation to the purchaser.

General market value requirement and exceptions

- Allocations must be based on the relative market values of the assets, except when the tax book value minimum on a unilateral vendor allocation applies to make the value allocated to a class of assets higher than market value, or the low-value depreciable property exception applies (see third bullet point below).

- The Commissioner can dispute an allocation that she considers is not based on relative market values.

- However, the Commissioner cannot challenge an allocation to an item of depreciable property if its original cost is less than $10,000, the total amount allocated to the item and any identical items is less than $1 million, and the amount allocated to the item is no less than its tax book value and no greater than its original cost.

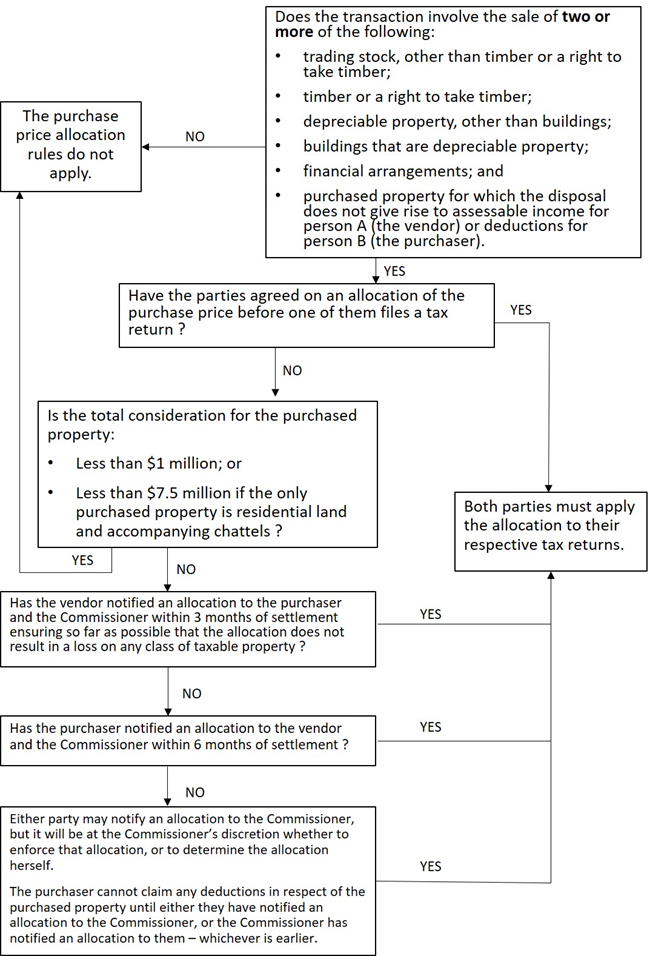

Figure 1 illustrates the application of the purchase price allocation rules.

Figure 1: Application of the purchase price allocation rules

Application date

The rules apply to agreements for the disposal and acquisition of property entered into on or after 1 July 2021.

Detailed analysis

Effect of purchase price allocation agreement

Generally, parties to a sale and purchase agreement who agree an allocation of the transaction price to specific assets will follow that agreement when filing their tax returns. However, sometimes, purchasers have agreed an allocation in a sale and purchase contract and then argued that they are entitled to use a different figure in their tax return, on the basis that the agreed figure is less than market value. New section GC 20 requires parties who have agreed a purchase price allocation in writing to file their income tax returns on the basis of that allocation, even if they do not think it reflects market values. This is achieved by section GC 20(2)(a).

Example 27

Dizrythmia Consultants Limited (DCL) enters into negotiations to sell its commercial office building to Double Happy Properties Limited (Double Happy). The sale consists of land (class (vi)), building (class (iv)), and building fit-out (class (iii)). DCL asks a price of $10 million, but states that this price is contingent on Double Happy agreeing to the following purchase price allocation:

| Item | Amount |

| Land | $4m (valuation) |

| Building | $4.5m (tax book value) |

| Fitout | $1.5m (tax book value) |

| Total | $10m |

Double Happy is convinced that the cost base for the building fit-out is too low – and has a valuation to support that view – but nevertheless agrees to the allocation because it considers $10 million to be an acceptable price for the whole bundle of assets.

DCL and Double Happy must file their respective returns of income on the basis of the agreed allocation.

If the Commissioner considers that the agreed amount does not reflect the relative market value of the class of property, the Commissioner can treat the class of property as disposed of and acquired for a different amount. This is achieved by section GC 20(2)(b). Relative market values should be determined either at the time the parties enter into their agreement or, if later, when they agree their allocation.

Section GC 20(3) is an exception to the Commissioner’s ability to challenge an agreed allocation. The Commissioner cannot challenge an allocation to an item of depreciable property if:

a) the original cost of the item for the vendor is less than $10,000, and

b) the total amount allocated to the item and to any identical items is less than $1 million, and

c) the amount allocated to the item is no less than its tax book value and no greater than its original cost.

This exception is primarily included to give certainty to vendors taking a low compliance cost approach to allocating to low-value depreciable assets.

Condition (a) of the exception sets the de minimis ceiling of a single item at $10,000.

Condition (b) is a caveat to condition (a). If there is a large number of identical low-value assets with an aggregate allocated value under the transaction of $1 million or more, the exception does not apply.

Example 28

Matinee Idyll Property Limited (Matinee) is selling a commercial building with 600 identical office desks. Matinee has agreed with the purchaser an allocation to depreciable property which is based on an aggregate allocation to the desks of $2 million – their tax book value. The desks were entered as one item on the vendor’s depreciation register. While the value of each individual desk is low, the aggregate value of the set is high, and any aggregate discrepancy between tax book value and market value could be material. Therefore, the Commissioner will retain the right to challenge an allocation in respect of these assets.

Condition (c) sets the range of unchallengeable values. The allocation must be no lower than tax book value and no higher than original cost. The rationale for this range is that the immediate effect of an allocation within it will be either revenue neutral or positive, and symmetrical. However, an allocation below tax book value would give the vendor a loss, and an allocation above original cost would give the vendor an untaxed capital gain but a higher cost base for the purchaser’s deductions.

Purchase price allocation required: no agreement

New section GC 21 provides a hierarchy of unilateral allocation rules that apply where the vendor and purchaser do not agree an allocation to the classes of property before the first tax return for the year of the transaction is filed. The purpose of these rules is to give parties a mechanism to file on the basis of a single allocation in cases where they are unable to agree one.

De minimis

Section GC 21(2) sets out two thresholds below which the unilateral allocation rules do not apply. A unilateral allocation does not need to be notified where the total consideration for the purchased property is less than:

a) $1 million, or

b) $7.5 million, if the only property in the disposal is residential land (which includes residential buildings) together with its chattels.

‘Consideration’ encompasses both the purchase price and the value of any vendor liabilities assumed by the purchaser (such as warranty obligations).

Example 29

Amy is selling her small software business – ‘Twelfth Dimension Software’ – to Titus. The business assets include software (class (iii)) and goodwill (class (vi)). Titus offers Amy $950,000 for the business, which Amy accepts. They do not agree a purchase price allocation between the software and goodwill, but because the total price is less than $1 million, and section EB 24 does not apply to the software or goodwill, they are not subject to any consistency rules. Therefore, they are able to adopt their own allocations in their tax returns, based on their own respective assessments of market value.

Suppose the facts are varied so that Titus also agrees to take over certain obligations to customers, which the parties value at $60,000 (in addition to the $950,000 cash payment). The consideration is now above the de minimis, and section GC 21 applies. The amount allocated to the business assets will of course be increased by the $60,000.

‘Residential land’ is defined in the Act and includes residential buildings. Chattels are any items sold with the residential building that do not form part of the building.

The vast majority of residential property sales will be below the $7.5 million threshold. Residential sales data for 2018–2021 shows there were only 115 sales at or above $7.5 million over the period – 0.03% of total sales. Of these, some are likely to have been sales of a house by one owner-occupier to another, which are not affected by the purchase price allocation rules, since all the property is outside the tax base for both parties. The residential transactions that are likely to be caught are sales of high-end rentals, or multi-dwelling buildings such as apartment blocks.

A higher threshold for residential property transactions is justified on the basis that residential buildings are non-depreciable, so the scope for tax manipulation in these transactions is low.

Example 30

Hermit McDermitt owns a number of high-end rental properties. One such property is located in a prime area in Nelson and Hermit has decided to sell the property. Sandy Allen has been looking for a property she can rent out to wealthy tourists once the borders have opened for travel and puts in an offer for the property of $7.2 million which is $1.5 million over the RV of the property and Hermit accepts this.

They do not allocate the purchase price between, land (class (vi)), house (class iv)) and chattels (class (iii)). Because the consideration is less than $7.5 million and the only property being sold is the land, house and chattels, the purchase price allocation rules do not apply. Section EE 45(10) requires Hermit McDermitt to allocate market value to the chattels.

If Hermit has been occupying the property as his main home, the sale will be non-taxable for him, and he will not need to make an allocation.

Vendor allocation

Section GC 21(3) provides that, if the vendor uses different income tax treatments for two or more of the classes of property (and is thus required to make an allocation), the vendor may notify the Commissioner and the purchaser of an allocation within three months of the change in ownership of the property. The amount allocated to each class of property must be the greater of the relative market value and the tax book value of the class. ‘Tax book value’ is defined in subsection (13) as: ‘the total amount that person A uses or would use, for purchased property in the class of property, in calculating person A’s tax position for their income year in which the change in ownership of the purchased property occurs.’

The tax book value minimum protects the purchaser from an unreasonably low allocation to taxable/deductible property by the vendor, which the Commissioner may not wish to challenge.

The vendor will not be able to comply with the tax book value floor where the aggregate tax book value of all the classes of taxable property plus the relative market value of the class of non-taxable property exceeds the total purchase price. This could be the case in a distressed sale where the vendor is making a genuine loss. Section GC 21(4) provides a mechanism to deal with the excess of the amount required to be allocated by the previous subsection above the total purchase price. The excess is applied:

a) first, to reduce any amount allocated to the class of non-taxable property (for example, goodwill, or non-taxable land)

b) second, to reduce, pro rata, any amounts allocated to the other classes of property.

Therefore, where the amount allocated to the class of non-taxable property is higher than the excess, the excess can be eliminated entirely by reducing the allocation to that class. Where the amount allocated to that class is already zero – whether by virtue of having been reduced by the first step, or of there being no non-taxable property in the transaction in the first place – the tax book values of the classes of taxable property must be reduced proportionately until they collectively equal the purchase price.

Example 31

Frenzy Fabrics Limited (Frenzy) is selling one of its factories to Poor Boy Pastels Limited (Poor Boy). The sale consists of land (class vi)), building (class (iv)), factory fit-out, and machinery (both class (iii)). During negotiation, Frenzy and Poor Boy try to reach agreement on an allocation, but Frenzy is adamant the fitout and machinery are worth $4 million less than tax book value of $7 million but that the land has appreciated significantly. Poor Boy claims the land has not moved much in value, but the machinery is worth closer to its original cost of $10 million. Frenzy has obtained a valuation for the underlying land that is much higher than Poor Boy’s assessment of the land value.

Despite not being able to agree an allocation with Frenzy, Poor Boy is committed to purchasing the factory, and the two companies complete the deal for $50 million.

Having not agreed an allocation with Poor Boy, Frenzy has the first allocation right under the new rules. Based on its valuation, Frenzy wants to make the following allocation:

| Item | Amount |

| Land | $35m (valuation) |

| Building | $12m (tax book value) |

| Fitout & machinery | $3m (own assessment of market value) |

| Total | $50m |

However, the aggregate tax book value of the fit-out and machinery is $7 million. Because Frenzy is making a unilateral allocation, it is required to allocate at least tax book value. Three weeks after settlement, it therefore notifies the following allocation to Poor Boy and to the Commissioner of Inland Revenue:

| Item | Amount |

| Land | $31m (valuation less additional allocation to fitout and machinery) |

| Building | $12m (tax book value) |

| Fitout & machinery | $7m (tax book value) |

| Total | $50m |

The allocation binds Poor Boy, and both companies file their returns on the basis of it, as required by the new rules. The Commissioner may only dispute the allocation of $7 million to fitout and machinery if she believes it is less than market value.

Purchaser allocation

In some cases, the vendor may not make an allocation. For example, if the vendor is a dealer (taxable on all the property), or tax exempt, they are not able to make one.

Section GC 21(5) provides that if the vendor does not notify an allocation within the three months, the purchaser may notify the Commissioner and the vendor of an allocation within six months of the change in ownership of the property. An allocated amount must reflect the relative market value of the relevant class of property proportional to the other classes of property. There are no other constraints on the purchaser’s allocation.

Parties must notify each other following the requirements of sections 14A to 14G of the Tax Administration Act 1994. This means that in the case of a purchaser allocation, so long as they do this it will not matter that the vendor may no longer exist at the time the purchaser notifies their allocation (for example, where the vendor has wound up or liquidated after settlement).

Example 32

Time and Tide Financing Limited (TnT) is selling its finance business as a going concern to Charlie. The business’s assets are receivables (financial arrangements class (v)), goodwill (class (vi)), and software (class (iii). TnT claims most of the business’s value is in the goodwill, and that the receivables should be significantly discounted because there has recently been an economic downturn and some of TnT’s clients have been laid off and had to enter into special debt repayment plans.

Charlie believes that the economy will soon recover and that the clients will pay quickly and in full and wants the receivables to be allocated their tax book value. They claim the goodwill is worth substantially less than TnT’s assessment.

The parties do not agree an allocation, but Charlie wants to go ahead with the transaction and buys the finance business for $8 million.

After settlement, the owners of TnT start focusing on their next business venture and neglect to notify a purchase price allocation to Charlie and the Commissioner. Three months pass, and Charlie – having received no allocation – notifies their own allocation, based on their assessment of market values, to the owners of TnT and to the Commissioner:

| Item | Amount |

| Receivables | $5m |

| Goodwill | $2m |

| Other intangibles | $1m |

| Total | $8m |

The allocation binds both parties and they file their respective tax returns on the basis of it, in accordance with the rules. The Commissioner may challenge this allocation, if satisfied it was not made on the basis of relative market values.

No timely notification

If no allocation is notified on a timely basis – that is, within six months of settlement – the power to determine the allocation passes to the Commissioner.

If the vendor or purchaser notifies an allocation after the six months, it will be at the Commissioner’s discretion whether to bind both parties to it, or to instead notify her own allocation in accordance with market values, which both parties must then adopt.

Where neither party notifies an allocation at any stage, they will still have to make allocations in filing their tax returns. Such allocations will be subject to adjustment by the Commissioner. The Commissioner may require a party to allocate, to the classes of purchased property:

a) the amounts allocated by the vendor to the classes of purchased property, or

b) the amounts allocated by the purchaser to the classes of purchased property, or

c) amounts that reflect the relative market value of the relevant class of purchased property, proportional to the other classes of purchased property.

The Commissioner will notify the required allocation to both the vendor and the purchaser, either for them to use in filing their respective tax returns, or – if they have already filed returns – in an amended assessment for one or both parties.

Allocated amounts enforced

Subsection GC 21(7) provides that a class of purchased property is treated as disposed of and acquired for the amount allocated under subsections (3) to (6). In effect, a unilateral vendor, purchaser, or Commissioner allocation is binding on the parties, with no right for a party to contest the allocation by filing a notice of proposed adjustment or to take any other proceedings to challenge the allocation. The Commissioner retains the right to dispute an allocation by one of the parties that is not market value, unless it is an allocation made in accordance with section GC 21(3)(b) and is higher than market value, or it is an allocation to low-value depreciable property protected by the exception (see section GC 21(11)).

No deductions for purchaser until allocation

To incentivise the purchaser to notify an allocation when they have the allocation right, sections GC 21(8) to (10) provide that the purchaser is not entitled to any deductions in relation to the purchased property until the first income year for which they file a return of income on a timely basis after the earlier of the following:

- The purchaser’s notification of their allocation to the Commissioner, and

- The Commissioner’s notification of her allocation to the purchaser.

The purchaser should therefore notify their allocation to the Commissioner and the vendor as soon as possible to ensure they can claim deductions in their next tax return, and not have them deferred. Any deductions that are deferred will be able to be claimed in the return that is filed on a timely basis after an allocation is notified to or by the Commissioner. This will result in the claiming of deductions for more than one year in a single return.

Example 33

Missing Person Detective Agency Limited (MPDA) a very successful private investigation firm has decided to sell its business to I Hope I Never Security Limited (IHNS) in the 2023–24 income year. The assets being sold are the building premises (class (iv)), fit out (class (iii)), customer database and goodwill (both class (vi)). MPDA and IHNS agree on a purchase price of $28m but don’t agree on an allocation.

Time moves on and neither MPDA nor IHNS notifies an allocation to the other party or the Commissioner. Both parties file tax returns for the 2023–24 income year recognising the transaction, with different allocations. MPDA allocates tax book value to its fit out, while IHNS allocates a greater amount.

In early 2026, when reviewing the 2023–24 tax return for IHNS, the Commissioner realises that no allocation has been notified by the parties. She determines that IHNS’s allocation is the more reasonable. She therefore issues an amended assessment to MPDA increasing its income in the 2023–24 year by the additional depreciation recovery implied by IHNS’s valuation. She also issues an amended assessment to IHNS denying a deduction for depreciation of the premises and fit out altogether for the 2023–24 year. These assessments trigger an obligation to pay UOMI, and shortfall penalties may also apply. IHNS will be able to claim the denied deductions in its next tax return, along with the deductions for that year.

Exception for low value depreciable property

The low value depreciable property exception in section GC 20(3) is replicated in section GC 21(11).

Relationship with other provisions of the Act

Several existing provisions in the Act deal with amounts allocated to property sold in a mixed supply.

Section EB 24 provides that when trading stock is disposed of together with other business assets, the sale proceeds must be apportioned between the trading stock and the other assets in a way that reflects their respective market values. Also, the purchaser must use the vendor’s allocation to the trading stock. Section DP 10 contains rules consistent with section EB 24 that relate solely to disposals of timber.

Section EE 45(10) provides that when depreciable property is sold with other items, the amount allocated to the depreciable property is its market value.

Section GC 21(12) provides that any such existing provision of the Act that expressly requires the use of market value for purchased property is overridden by the purchase price allocation rules to the extent to which the amount allocated to that property is determined under the purchase price allocation rules.

This override serves two main purposes. First, it prevents parties from attempting to use two different market values for an item or class of property on the argument that one value is determined under the purchase price allocation rules and another is determined under a different provision of the Act. Second, it allows the tax book value floor on a unilateral vendor allocation to operate correctly; where the relative market value of a class of property is lower than its tax book value, the tax book value is used.

Example 34

Parrot Fashion Pines Ltd (PFP) is selling one of its forests, which comprises trees (timber, class (ii) and freehold land (class (vi)), along with depreciable equipment (class (iii))with a cost of $73,000 and a book value of $20,000. PFP has incurred expenditure on the land within various categories described in schedule 20 Part G of the Income Tax Act 2007. The original amount of such expenditure was $150,000, and it has been depreciated down to $85,000 at the end of the year before the sale, using the rates provided for in Part G.

PFP and the buyer, Bold as Brass Ltd have agreed a price and an allocation of:

| Item | Amount |

| Depreciable Property | $20,000 |

| Land | $1,800,000 |

| Trees | $180,000 |

| Total | $2,000,000 |

PFP will recognize $180,000 income from the sale of trees, no depreciation recapture, and no other income. Bold as Brass will have a cost of trees of $180,000, depreciable property of $20,000, and an amortisation deduction in the year of sale of the appropriate percentage of the $85,000 of unamortised land related costs under section DP 3 (provided PFP gives Bold as Brass a record of this expenditure). There is no requirement for an allocation of the purchase price to the unamortised land related costs – these costs will generally be reflected in the value of land or other improvements. The allocation to timber is subject to the Commissioner’s right to dispute it if she considers it is not in accordance with relative market value (section GC 20(2)(b)).

First variation

Assume that:

- PFP bought the forest by way of an asset purchase 2 years before the sale to Bold as Brass and paid $300,000 for the trees (log prices have declined significantly since then). PFP has not incurred any other expenditure which has had to be added to the cost of timber, and

- PFP and Bold as Brass have not agreed an allocation.

If PFP makes an allocation under section GC 21(3), it must treat itself as selling the trees for $300,000 for tax purposes. This will also be Bold as Brass’s cost for the trees. This will reduce the allocation to land to $1,680,000.

Second variation

Assume that Bold as Brass and PFP are associated parties, and that they have agreed the $180,000 allocation to the timber. In this case, the sale price will be respected for tax purposes (subject to the Commissioner’s ability to challenge it as not in accordance with relative market values). However, PFP will only be entitled to deduct $180,000 as cost of timber (section DP 10(4)) and Bold as Brass will add the “missing” $120,000 to its cost of timber (section DP 10(5)), giving it a cost of $300,000.

When a mixed supply involves an acquisition of depreciable property by a person (purchaser) from an associate (vendor), sections GC 20 and GC 21 operate in conjunction with section EE 40(7), which limits the amount of depreciation that can be claimed in such a case. The person’s depreciation claim is based on the lesser of the cost to the person and the cost to the associate. While the cost to the person is determined by sections GC 20 or GC 21 if the acquisition from the associate was a mixed supply, if this amount is greater than the cost of the item to the associate, the person’s depreciation claim is based on the lesser amount.

Definitions

Section GC 21(13) provides definitions for three terms used in the purchase price allocation provisions.

The term ‘allocation notification’ is used in sections GC 21(9) and (10), which defer a purchaser’s deductions. ‘Allocation notification’ means the earliest of the following:

i) the time when the purchaser’s notification of their allocation is provided to the Commissioner in the form prescribed by the Commissioner, and

ii) the time when the Commissioner’s notification of her allocation under subsection (6) is provided to the purchaser.

The term ‘pre-allocation deduction’ is also used in sections GC 21(9) and (10). It means the purchaser’s deductions for purchased property that, ignoring sections GC 21(9) and (10), would be allocated to an income year before the income year in which allocation notification occurs. In effect, pre-allocation deductions are the deductions that are deferred.

The term ‘tax book value’ is used in sections GC 20(3)(c)(ii), GC 21(3)(b) and GC 21(11)(c)(ii). ‘Tax book value’ means the total amount that the vendor uses or would use, for purchased property in the class of property, in calculating their tax position for their income year in which the change in ownership of the property occurs.

For trading stock, the tax book value is the value of the stock on hand at the time of the transaction as calculated under the valuation method used by the vendor for the income year in which the transaction takes place.

For depreciable property, the tax book value is the amount the property has been written down to at the end of the year before the transaction, less a pro rata portion of the depreciation for the vendor in the year of the transaction.

For financial arrangements, the tax book value is the consideration that would give an amount of income or expenditure under section EW 31 (base price adjustment formula) equal to the income or expenditure the vendor would have for the purchased property in the year of the transaction, for the part-year period before the transaction, using the relevant spreading method for the property for the part-year period, pro-rata.

Subsection (b) of the trading stock definition in section YA 1 is amended to include sections GC 20 and GC 21. This means that in the purchase price allocation rules, trading stock:

i) includes anything produced or manufactured

ii) includes anything acquired for the purposes of manufacture or disposal

iii) includes livestock

iv) includes timber or a right to take timber

v) includes land whose disposal would produce income under any of sections CB 6A to CB 15 (which relate to income from land)

vi) includes anything for which expenditure is incurred and which would be trading stock if possession of it were taken

vii) does not include a financial arrangement to which the financial arrangement rules or the old financial arrangement rules apply.

This is the broad definition of trading stock used for the purposes of section EB 24 and several other sections.

Notifications by vendor or purchaser

Notification to the Commissioner of an allocation should be made online via MyIR, or via a letter. This notification should include the phrase “Purchase Price Allocation” in the subject line and contain the following information:

- The names, IRD/GST numbers and contact details of the vendor and purchaser

- The date of agreement to the transaction

- The date on which the property was transferred (that is, settlement/change in ownership)

- The total consideration (including the value of any liabilities assumed)

- The amounts allocated to each of the following classes of property sold, allocating zero to any class of property not sold:

i) trading stock, other than timber or a right to take timber

ii) timber or a right to take timber

iii) depreciable property, other than buildings

iv) buildings that are depreciable property

v) financial arrangements, and

vi) purchased property for which the disposal does not give rise to assessable income for person A (the vendor) or deductions for person B (the purchaser)

- A statement that the amounts have been allocated in accordance with section GC 21

- If desired, supporting documents such as the sale and purchase agreement and the notification provided to the other party.

Practical variations

Nominees

In some transactions the acquirer of the purchased property will be a nominee of the purchaser, rather than the purchaser named in the contract. If the vendor agrees an allocation with the purchaser, and the agreement also allows for nomination, the vendor should include a provision in the sale and purchase agreement to ensure that any nominee is bound to that agreed allocation. If the vendor makes a unilateral allocation under section GC 21, that allocation will bind the purchaser or the nominee without the need for any special contractual provision.

Mortgagee sales

The purchase price allocation rules may apply to a mortgagee sale, where the vendor is a bank or other lender (mortgagee) recovering funds by selling the property of an owner (mortgagor) who can no longer meet their repayment obligations. Neither the mortgagee nor the mortgagor is likely to be engaged on the issue of allocation, but if the purchaser wants to agree an allocation with the mortgagee, they should ensure that the mortgagee has been authorised by the mortgagor to agree an allocation.

Auctions and tenders

In competitive bid processes such as auctions and tenders, purchasers may often have to submit bids without the opportunity to agree a purchase price allocation. The outcome of the initial bidding process could be influenced by whether particular bidders have specified a potential purchase price allocation, since the allocation could impact on the vendor’s returns.

Parties may navigate these commercial realities in a number of ways. For example, in a tender, purchasers may express bids as being conditional on a specified allocation. Or the vendor in an auction may specify an allocation, to ensure that all bids are made on an even footing.

Purchase price adjustments

When an agreement provides for contingent payments to be made, the amount of those payments will often not be known before the parties agree an allocation or make a unilateral allocation. However, the parties may agree, or in the case of a unilateral allocation, specify, the “in principle” allocation of those payments to particular categories of assets. For example, earn out payments may be allocated to goodwill. If the allocation is agreed or specified in that way, sections GC 20 and GC 21 should apply to that allocation in the same way as they apply to non-contingent payments. If the non-contingent amounts have not been allocated in that way, their allocation will be dealt with under existing law.

Dealers and tax-exempt parties

In some transactions the vendor or purchaser may treat the entire amount of the consideration in the same way. This will be the case if the party is a dealer or an exempt entity.

A dealer or exempt party is not able to make an allocation. If the other party to the transaction is required to make an allocation because they use two or more different tax treatments for the purchased property, then as a practical matter that other party will be able to determine the allocation. Whether the formal mechanism for this is agreement or a unilateral allocation should not be significant, since the dealer or exempt party will not be applying the allocation in any event.

Where both parties to a transaction are dealers or exempt entities, the purchase price allocation rules do not apply.