Modernising tax administration - Other items

- Overpaid PAYE income not repaid

- Overpayments and employment related loans

- Mid year entry to the accounting income method

- Amending the payment allocation rules

- Correction of unintended change in the provisional tax and use-of-money interest rules

- Update of obsolete cross-references

OVERPAID PAYE INCOME NOT REPAID

(Clauses 119, 194–198, 213(24) and 213(33))

Summary of proposed amendments

This amendment provides that an overpayment of employment income subject to PAYE which is not repaid remains taxable as PAYE income.

Application date

The proposed amendment will come into force on 1 April 2019.

Key features

Proposed amendments include overpayments of employment income subject to PAYE that are not repaid in the scope of sections CE 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007 (amounts derived in connection with employment) and RD 3 (PAYE income payments). An “unrepaid PAYE income overpayment” is defined in proposed new section RD 8B.

A further amendment is proposed to section CE 1 to make it explicit that where a PAYE-related overpayment is repaid it is not income of the person.

Background

Employers prioritise paying staff on time over complete accuracy. Overpayments can occur for a number of reasons, including the late receipt of information and anticipated leave where the employee resigns before the leave is due. In most situations the overpayment is repaid by the employee and the employer notifies Inland Revenue of an adjustment to the previously filed information. Notification results in a refund or credit of the PAYE and other deductions to the employer and a reduction in the employee’s record of income and associated tax credits.

In some circumstances, the overpayment is not repaid. The proposed amendment deems that where a PAYE-related employment overpayment is not repaid the amount is income subject to PAYE.

While the current legal position is that overpayments not repaid are not amounts derived in connection with employment and should be treated as a tax free windfall many overpayments arise from anticipated leave which may be a condition of employment. The proposed amendment is intended to clarify the taxable status of all employment overpayments in a way which minimises employer compliance costs and accords with the common-sense view that overpaid salary or wages, extra pays or schedular payments, were paid in connection with employment. This is understood to be how some employers already treat overpayments which are not repaid. As a consequence of the proposed changes, the employer would be unable to recover PAYE on overpayments not repaid and the unrepaid amounts will remain on the employee’s record of income for social policy purposes.

Detailed analysis

All references are to the Income Tax Act 2007 unless stated otherwise.

Under current law, an overpayment of employment income subject to PAYE is not considered to be an amount derived in connection with employment. It is therefore neither employment income under section CE 1 employment income under section RD 3.

An amendment is proposed to the scope of section CE (1)1 so that an unrepaid employment income overpayment is income of the person. The proposed amendment also states that a repaid overpayment is not income of the person.

A proposed amendment to section RD 3 includes an “unrepaid PAYE income overpayment” as a PAYE income payment, to which the PAYE rules apply.

Amendments are proposed to each of sections RD 5 (Salary or wages); RD 7 (Extra pay) and RD 8 (schedular payments) to include in the scope of the provision an unrepaid PAYE income overpayment that was originally treated as a payment in the relevant category.

A PAYE-related overpayment is defined in proposed new section RD 8B as an amount paid in error to which the employee is not entitled or, an advance payment to which the employee does not subsequently become entitled (such as can happen with anticipated leave if the employee leaves before being entitled to the leave). The definition also requires that the amount was originally paid as salary or wages, an extra pay or a schedular payment.

An unrepaid employment income overpayment is defined in proposed section RD 8B(3) as a PAYE-related overpayment that has not been repaid to the employer. Employer’s superannuation contributions, other than those the employee has chosen to have treated as salary or wages, are excluded from this definition as are amounts that are income of the person under section CB 32 (property obtained by theft).

OVERPAYMENTS AND EMPLOYMENT RELATED LOANS

(Clause 126)

All references are to the Income Tax Act 2007 unless stated otherwise.

Summary of proposed amendments

The Bill proposes to amend section CX 10 so that an overpayment of employment income subject to PAYE does not amount to an employment-related loan on which a fringe benefit arises.

Application date

The proposed amendment will come into force on 1 April 2019.

Background

Frequently, when an overpayment is made the employer and employee will agree that it will be repaid over time.

Technically an overpayment could be regarded as a loan to the employee until it is repaid. The amendment clarifies that the scope of employment related loans which give rise to a fringe benefit excludes a PAYE-related overpayment.

Key features

An amendment is proposed to add new section CX 10(2)(bb). The amendment would exclude a PAYE-related overpayment from the scope of “employment-related loans” in section CX 10(1).

Under the proposed amendment no liability for fringe benefit tax would arise because of the overpayment, even if the employer allowed an interest free period for it to be repaid.

MID YEAR ENTRY TO THE ACCOUNTING INCOME METHOD

(Clauses 190–192)

Summary of proposed amendment

Currently taxpayers who are otherwise eligible to pay provisional tax under the accounting income method (AIM) can only elect to use AIM prior to their first payment date under AIM. Once the income year has commenced this is likely to mean they will have to wait until the next income year to use AIM. This amendment allows those taxpayers who currently use another provisional tax method (other than the estimation method) to switch to AIM at any time during an income year prior to the final payment due under AIM for that person.

Application date

The proposed amendment will apply from the start of the 2019–20 income year.

Key features

The proposed amendment allows a taxpayer, who otherwise meets the criteria to use AIM to switch to that method from either the standard or GST ratio method at any time during the income year prior to the final due date for AIM for that taxpayer as long as they have made the required payments under that prior method.

Background

The Taxation (Business Tax, Exchange of Information, and Remedial Matters) Act 2017 inserted a new provisional tax method into the Income Tax Act 2007. The accounting income method (AIM) allows taxpayers who meet the requirements within section RC 5(5B) to calculate their provisional tax payments on a pay-as-you-go basis.

Where a taxpayer who meets the criteria of section RC 5(5B) elects to use AIM they must make that choice “on or before the first instalment date for them under the AIM method”. This allows new businesses to commence using AIM during an income year (as long as they choose to do this prior to their first AIM payment due for that year). Existing businesses must wait until the following income year to choose to use the AIM method.

In order to make the transition to AIM more attractive to taxpayers, it is proposed to allow those, who otherwise meet the criteria to use AIM, to switch to AIM during the income year rather than having to wait until the following income year.

Detailed analysis

Taxpayers who otherwise meet the criteria in section RC 5(5B) of the Income Tax Act 2007 will be permitted to switch to the AIM method at any time prior to the final AIM payment where:

- they use another concessionary provisional tax method (that is, either the standard or the GST ratio method); and

- they have made all payments due under those methods prior to the date of switching to the AIM method.

Example 6

McGarrett Enterprises Limited (McGarrett) is the maker of flower leis for tourist operators. McGarrett has historically made their provisional tax payments under the standard method. After talking with a number of other small business owners Steve, McGarrett’s owner, decides that because of the seasonality of the lei business it would be better using the AIM method. McGarrett is part way through its 2020–21 income year. It has a March year end and has made its first two provisional tax payments totalling $5,000 on the 7th of August and 15th of January in full and on time.

McGarrett has already been using an AIM capable software product but has not turned the AIM function on. He does that at the end of January. This will mean his first AIM payment is due on the 28th of February. McGarrett switches on the AIM calculation part of his accounting software and it calculates that at the end of January McGarrett owes $6,200 in provisional tax. McGarrett makes an AIM payment of $1,200. Because McGarrett is switching from the standard method to AIM and has made all its payments due under the prior method, it can then make the switch to the AIM method during the year. McGarrett meets all the other requirements to use the AIM method.

Example 7

Dr Max’s Malasadas Limited (DMM) is the manufacturer of specialty Hawaiian donuts. It has a turnover of $3.5m and uses accounting software to maintain its business records. That software is AIM capable and because of the volatility of DMM’s sales, Dr Max, the owner, decides that it would be better to use the AIM method for provisional tax rather than the current standard method. DMM is part way through their 2021–22 income year and is just completing the September month end. It has a March balance date and DMM’s first instalment of provisional tax was due on 7th of August. Unfortunately because of some cashflow issues DMM did not make that payment. DMM decides to switch to the AIM method and turns on the AIM capability in the software. However, as DMM has not made the payments required under the standard method it will be prohibited from switching to AIM during the year and will need to wait until the following income year to make the switch.

Taxpayers who pay, or fund their provisional tax through a tax pooling intermediary will need to transfer any funds from the pooling entity to Inland Revenue prior to the switch from the previous method to the AIM method.

Example 8

Kono Kameras Limited (Kono) sells travel cameras which take photos that make the subjects always look like they are on Waikiki beach. This is a limited market but can be volatile as people see photos taken by a Kono Kamera on the internet and then want a Kamera rather than actually travelling to Waikiki. Because of cashflow difficulties Kono uses a tax pooling intermediary to finance its provisional tax payments. During the 2020–21 income year Kono decides that using the AIM method would better suit its cashflow situation and decides to make the switch. Kono already uses accounting software to keep its accounts in order and that software is AIM capable.

Kono has financed its first instalment of provisional tax which was due on the 7th of August 2020, those funds have not yet been credited to Kono’s account at Inland Revenue. Prior to making the switch to AIM, Kono will need to transfer those funds to Inland Revenue as otherwise it will appear that Kono has not made the payments required under the prior method and it will not be permitted to switch.

AMENDING THE PAYMENT ALLOCATION RULES

(Clause 75)

Summary of proposed amendment

This amendment alters the current payment allocation rules to allow Inland Revenue to continue to apply payments towards use-of-money interest (UOMI) first but to the oldest debt within a period first. This method will result in a larger proportion of payments being allocated to core tax liabilities which will reduce any overall UOMI cost to taxpayers. It is required to facilitate a change to the way in which Inland Revenue’s computer system allocates billing items within a period.

In no case will the new method of allocation result in a greater charge for UOMI than under the current allocation rule.

Application date

The proposed amendment will apply from 17 April 2018, the date when the second tranche of Inland Revenue’s processes transition to its new technology platform.

Key features

This proposed amendment requires the Commissioner to allocate payments in a specific order first towards UOMI and then core tax but clearing the oldest UOMI and debt first within a tax period. The amendment allocates a larger proportion of payments to core tax liabilities than UOMI when compared to the current rule.

Background

The Tax Administration Act 1994 contains a payment allocation rule in section 120F which deals with how a taxpayer’s payment is allocated to amounts payable within a period. This rule requires that where the taxpayer has unpaid tax and they are liable to pay UOMI on that unpaid tax then payments are allocated to interest liabilities first and then core tax and penalties.

This is primarily driven by the fact that UOMI is charged on a “simple” basis in that interest is not compounding (that is, interest does not accrue on interest). If there were a balance of UOMI outstanding on a taxpayer’s account, there is little incentive to pay that amount as it is “interest free” debt.

This payment allocation rule works well when you consider tax liabilities within a period balance in that there is one liability within a period. Where there are multiple liabilities within a period this allocation rule can be problematic.

Inland Revenue’s current technology platform uses a reverse and replace model for reassessments. When a taxpayers’ assessment of tax is amended, the current system reverses the old assessment and replaces that with the new assessment.

This means there is only one liability within a period for a taxpayer. A decision has been made to move away from this reverse and replace model to a new method termed a “delta” model. Instead of replacing the original assessment it adds the difference, or delta, as an additional billing item within the tax period. The delta model only applies to debit (or additional) assessments. The reverse and replace method continues for credit (or reduced) assessments.

For billing purposes taxpayers will not necessarily see these delta amounts as they will appear as a combined liability within a period. This change to a delta model necessitates a change in the way that payments are allocated to avoid any billing issues for taxpayers.

Detailed analysis

The difference between the “reverse and replace” and the “delta” models is that instead of the initial assessment being “reversed and replaced” with the new assessment amount under the delta model, the original assessment is left in the period and the additional amount, or delta, is added to the period. This amount may have the same or a different due date than the original assessment.

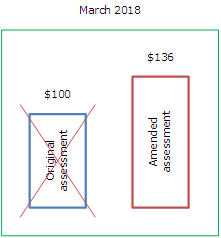

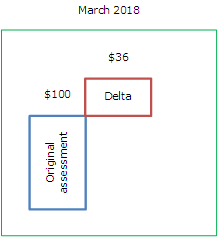

Example 9

A taxpayer files their return for the March 2018 goods and services tax period which has a tax payable amount of $100. In April the Commissioner amends that return and increases the tax payable amount to $136. Under a reverse and replace model the following occurs.

(Source: SVG)

The original assessment in blue is replaced with the new assessment in red within the March 2018 period.

Under a delta model the following occurs:

(Source: SVG)

The original assessment remains with the additional assessment (in red) added. This additional amount may, or may not, have a different due date but is treated as a separate billing item within the system.

In either scenario the taxpayer will see an assessment amount for $136 (although that amount may have sub-amounts due at different dates which will be stated).

Under the reverse and replace method there is only one billing item per tax period and the current payment allocation rules work well to ensure there is no leftover UOMI. Also the billing to taxpayers is simple to understand as it displays one amount payable.

The delta model can have presentational and billing issues where payments received are not allocated to the oldest billing item within a period balance first. The result can be multiple statements issued for separate billing items with small balances within a period which can cause confusion for the taxpayer. It can also result in amounts changing because of payment reallocations to reflect the “interest first” rule.

This could, in certain circumstances, result in an increased amount of interest being charged to taxpayers over the current position.

An amendment is required to the payment allocation rule that continues with the concept of interest first but within billing items rather than the period balance. This essentially means a first-in-first-out system whereby the oldest billing item is settled first.

This model will simplify the system design and also the impact on the taxpayer as the recalculation of interest, where there are multiple adjustments, will be eliminated. The payment allocation will continue to ensure there is no balance of “interest only” within a tax period as the payment will still apply to interest first within a billing item rather than the period.

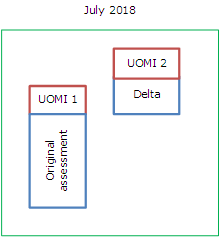

Example 10

Dannos Drivers Limited (Danno) is a New Zealand ride sharing company. Danno has been in business for a few years and files its July 2018 GST return to Inland Revenue.

During a routine review of Danno’s tax return, Inland Revenue finds than Danno has under declared the GST owing for the period. Inland Revenue issues Danno with a reassessment for that amount. Danno has already paid the amount of the original assessment a few days late and pays the remaining GST and resulting UOMI by the due date required by Inland Revenue.

Under the delta model the reassessment delta is illustrated as follows:

(Source: SVG)

Under the proposed payment allocation model the payment order would be:

UOMI 1

Original assessment

UOMI 2

Delta

The current rule would require the following payment allocation:

UOMI 1 and UOMI 2

Original assessment and Delta

Clause 75 replaces existing section 120F(1) which provides for a rule as to how payments are allocated. The current section provides for payments to be allocated to UOMI first and then core tax debt.

With the change to a delta model the current payment allocation rule can create some difficulties with billing which could be confusing to taxpayers. The new section 120F(1) will continue with the general rule of applying payments to UOMI first but will do this to the oldest debt within a period first. For most taxpayers there will be no difference from the change in the payment allocation method but for some it will result in less UOMI being charged than currently. This is because of a larger portion of a payment being allocated to core tax rather than UOMI. The new provision also includes an example to illustrate how the new rules will work.

Example 11: New section 120F(1)

On 1 September 2019, an assessment of $100 tax to pay is raised for the 2018–19 tax year. This amount incurs $5 use-of-money interest. On 1 September 2020 a re-assessment of $120 tax to pay is raised for the 2018–19 tax year along with an additional amount of $3 UOMI. The taxpayer pays the balance of $128. Payments are applied against the $5 use-of-money interest (that is, interest on the earliest unpaid amount), then against the $100 tax. Next, payments are applied against the $3 use-of-money interest on $20 tax to pay, then against the $20 tax.

CORRECTION OF UNINTENDED CHANGE IN THE PROVISIONAL TAX AND USE-OF-MONEY INTEREST RULES

(Clause 76)

Summary of proposed amendment

This amendment corrects an unintended change to the application of the use-of-money interest (UOMI) rules to taxpayers who are not new provisional taxpayers but who are only required to pay provisional tax in one or two instalments. This amendment restores the intended policy position to that prior to the unintended change and includes a savings provision for a very limited number of taxpayers who have requested and received cancellation of UOMI under the unintended legislation.

Application date

The proposed amendment will apply from 1 October 2007 – the date the unintended change was enacted.

Key features

The amendment restores the correct policy position on the application of UOMI to taxpayers who are not new provisional taxpayers but pay tax in one or two instalments instead of the usual three instalments. It was always intended that UOMI would apply across the three instalments of provisional tax notwithstanding a taxpayer may only have one or two instalments.

Background

An unintended change to the policy intention of the rules which calculate UOMI was made when the Taxation (Depreciation, Payment Dates Alignment, FBT, and Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill 2005 was enacted that may have had the effect of changing the well-established position that UOMI was charged over an entire income year for all but new provisional taxpayers. This amendment clarifies the legislation to ensure it continues to reflect the correct policy intent.

Detailed analysis

The Taxation (Depreciation, Payment Dates Alignment, FBT, and Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill 2005 included changes to align the payment dates for provisional tax and goods and services tax with effect from 1 October 2007. As part of that Bill, section 120K of the Tax Administration Act 1994 was repealed and replaced with sections 120KB–KE. Section 120K(1) clearly stated a general rule for the calculation of UOMI on provisional tax which applied unless any of the subsections within it modified that position. It read:

“Except where this section requires otherwise, in a tax year, other than a transitional year, a provisional taxpayer’s residual income tax is due and payable in equal instalments on each of the 3 instalment dates for the year”

There were a number of exceptions to this rule and in particular new provisional taxpayers, safe harbour taxpayers and those in a transitional year had their own special rules.

Section 120K was essentially replaced with section 120KB(2) which reads:

“A provisional taxpayer’s residual income tax is due and payable as set out in RC 9 of the Income Tax Act 2007”

Again this general rule does not apply to new provisional taxpayers, safe harbour taxpayers or those in a transitional year.

For most taxpayers this change in wording has no impact in that most provisional taxpayers will pay their provisional tax over three instalments. However, for a small subset of taxpayers who have not yet furnished their tax return for a prior income year, because of an extension of time, and who in the year previous to that year had residual income tax of less than $2,500 (and consequently were not a provisional taxpayer in that year) may interpret the wording differently. This wording change can arguably be read as suggesting that their residual income tax should only be apportioned over the number of instalments given by section RC 13 or 14 rather than over three instalments as intended.

At the time of the change there was no discussion of the change in policy for those particular taxpayers in any consultation process, nor was any change to that policy indicated in any Taxation Information Bulletin at the time. In addition, Inland Revenue systems were not altered to reflect any policy change at that time.

This amendment clarifies the legislation to reflect the intended policy position of residual income tax being due and payable over three instalments where, because of those criteria, a person only has one or two instalments of provisional tax due. From the 2018–19 year, when changes were made to the standard method of provisional tax, which in most cases will result in taxpayers only being subject to UOMI from their final instalment date, the scope of this issue arising has reduced but it is not eliminated.

As this change in the wording of this section was untended, the amendment to clarify the wording will apply at the same date the wording was changed. However, officials are aware of a very limited number of cases where taxpayers have challenged this position and may have had UOMI cancelled to reflect this alternative interpretation. Therefore, for those taxpayers who have received a cancellation of UOMI, a savings provision will be inserted to preserve that treatment for taxpayers who have challenged that position prior to the introduction of this Bill and received a cancellation of UOMI.

Example 12

Kamekona Shrimp Trucks Limited (Kamekona) owns a fleet of shrimp trucks that sell world famous garlic shrimp and poke around New Zealand using a fleet of trucks. Kamekona started business in the 2010 year, and it struggled to earn substantial amounts and thus was never a provisional taxpayer in those years. In 2014 its residual income tax was $2,200 for example.

In the 2015 income year, as Kamekona’s poke won the prestigious Chin Ho award for the best Hawaiian cuisine outside the Hawaiian Islands, sales from the trucks took off and the company had residual income tax of $120,000 for the 2015 year, making it a provisional taxpayer for that year. Kamekona uses a tax agent to manage its tax affairs and the company has an extension of time to file its tax return for the 2016 year.

Kamekona is not a new provisional taxpayer (as they had derived income from a taxable activity in the four years prior to the 2017 year) and it has an extension of time which means it does not need to file its 2016 tax return until 31 March 2017. Section RC 9(4)(c) of the Income Tax Act 2007 states that Kamekona does not need to pay provisional tax in three instalments. Section RC 9(10) then says that Kamekona can pay provisional tax in one instalment following the rules in section RC 14. Kamekona pays $200,000 in provisional tax on 7 May 2018 (the third instalment date) for the 2017 income year.

For the 2017 income year Kemekona’s residual income tax actually works out to be $300,000. This amount should be apportioned over the three provisional tax instalment dates (Period 1 to Period 3) for the 2017 year and UOMI should be charged accordingly. At Period 1 and Period 2 UOMI should be calculated on $100,000 less the amount paid of zero from the respective payment dates through to Period 3 and then on $100,000 from Period 3 being the difference between the $300,000 residual income tax and the $200,000 paid.

It is arguable the current wording of the legislation would only apportion the residual income tax to Kamekona at Period 3, although this was not the policy intent as UOMI is a use of money charge and the taxpayer had the use of those funds throughout the entire year. The amendment clarifies the policy intent.

UPDATE OF OBSOLETE CROSS-REFERENCES

(Clauses 207–210)

Summary of proposed amendment

This amendment corrects some cross-references in the Income Tax Act 2007 which refer to repealed section 120K of the Tax Administration Act 1994. The amendment references those sections more generally to Part 7 of the Tax Administration Act 1994.

Application date

The proposed amendment will apply from 1 October 2007 – the date section 120K was repealed. There are no adverse implications that officials can see from this application date for taxpayers.

Key features

The following four sections in the Income Tax Act 2007 refer to section 120K of the Tax Administration Act 1994, which has been repealed:

- RM 16(3);

- RM 22(5);

- RM 25(3); and

- RM 31(3).

The amendment references these sections to Part 7 of the Tax Administration Act 1994.