Simplified business tax processes

A special report from Policy and Strategy, Inland Revenue. February 2017

Simplified business tax processes

- Safe harbour for all taxpayers using the standard provisional tax method

- Safe harbour from use-of-money interest

- Allowing contractors to elect their own withholding rate

- Extending withholding to labour-hire firm contractors

- Voluntary withholding agreements

- Use-of-money interest and transfers of tax

- Prescribed forms

- Administration of the late payment penalty rules

- Cancellation of interest

This special report provides early information on changes to business tax rules contained in the Taxation (Business Tax, Exchange of Information, and Remedial Matters) Act 2017, enacted on 21 February 2017.

This special report covers changes to:

- modify the application of use-of-money interest (UOMI) for taxpayers who make all but their last instalment of provisional tax using the standard “uplift” method;

- increase the safe harbour from UOMI from $50,000 to $60,000 of residual income tax and extend the safe harbour to non-individual taxpayers;

- allow contractors subject to the schedular payment rules to elect their own withholding rate;

- extend the schedular payment rules to contractors who work for labour-hire firms;

- allow contractors not covered by the schedular payment rules to enter voluntary withholding agreements;

- prevent taxpayers from transferring tax to an earlier period that exceeds the amount in debt or in dispute in that period, and to clarify when UOMI starts and when a transfer takes effect for GST refunds and GST overpayments;

- enable the Commissioner to offset any credits or refunds the taxpayer has against the taxpayer’s tax liability arising from a new or increased assessment by the Commissioner;

- confirm that information required under a prescribed form can be provided verbally when the Commissioner of Inland Revenue considers it to be appropriate;

- enable Inland Revenue to continue to administer the late payment penalty grace period during the period in which tax types are transitioned between Inland Revenue’s old FIRST system and new START software systems; and

- modify the cancellation of interest rules, in certain circumstances.

Information in this special report precedes complete coverage of the new legislation that will be published in a future edition of the Tax Information Bulletin.

Safe harbour for all taxpayers using the standard provisional tax method

Amendments have been made which modify the application of UOMI to taxpayers who make all but their last instalment of provisional tax using the standard method (commonly known as the standard “uplift” method). For these taxpayers, UOMI will no longer apply from the first instalment. Instead, it will commence from the date of the final instalment of provisional tax.

Background

Under the previous rules, taxpayers who used the standard method for paying provisional tax but exceeded the safe harbour threshold of $60,000 residual income tax were liable to UOMI from the first instalment when their residual income tax for that instalment differed from the amount paid.

For taxpayers who cannot reasonably estimate their income (such as taxpayers with volatile or seasonal income) and who use the standard method, the previous rule could be unfair as provisional tax assumes a straight-line earning of income throughout a year.

The new Act introduces a new rule so that where a taxpayer makes all their provisional tax instalments (except for the final instalment) using the standard method on the respective payment dates UOMI will only apply from the date of the final instalment on the difference between the residual income tax and the payments made.

This change was announced by the Government in a pre-Budget release in April 2016 and the proposals consulted on in an officials’ issues paper, Making Tax Simpler – Better Business Tax, released in April 2016.

Feedback following consultation at the select committee stage of the bill resulted in some changes to the technical detail of the proposal. These do not alter the policy intent of the original proposal.

Key features

For taxpayers who pay their provisional tax using the standard method and do not qualify for the safe harbour, UOMI will only apply from the date of the final instalment when:

- the taxpayer has made all of their instalments (other than the final instalment) using the standard method;

- has paid those instalments on or before the due date;

- any provisional tax associates have also used the standard method for all of their instalments (other than the final instalment); and

- there is no provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement.

For taxpayers using the standard method who do not meet the above criteria, UOMI will apply from the applicable instalment date on the lesser of the difference between:

- the amount of residual income tax apportioned to the particular instalment date and the amount paid by the taxpayer; or

- the amount of the standard method instalment for the particular instalment date and the amount paid by the taxpayer.

A “provisional tax associate” of a person (person A) is defined as follows:

- If person A is a company, another company in the same wholly owned group as person A is a “provisional tax associate”.

- If person A is a company, another person who has a direct or indirect shareholding interest in the company greater than 50 percent is a “provisional tax associate”.

- If person A is not a company or is a company acting as a trustee, another person in which person A has a direct or indirect shareholding interest greater than 50 percent is a “provisional tax associate”.

A provisional tax avoidance arrangement is an arrangement involving the manipulation of one or more amounts of residual income tax, including a zero amount of residual income tax, with the purpose or effect of defeating the intent and application of the UOMI provisions. It is intended to capture situations where taxpayers who are outside the “provisional tax associate” definition manipulate income between parties to avoid application of the UOMI rules. It is intended to apply only in cases of clear manipulation to remove parties from the UOMI rules.

Application date

The new UOMI rules for standard method taxpayers in section 120KBB of the Tax Administration Act 1994 apply for the 2017–18 and later income years.

Detailed analysis

A comprehensive UOMI regime applies to all provisional taxpayers who do not fall within a specified safe harbour. Where a taxpayer’s residual income tax apportioned over the number of provisional tax instalment dates differs from the amounts paid by the taxpayer, over or underpaid tax will arise and UOMI will apply to the difference. This applies even if a taxpayer has made the required instalments under the standard method.

The standard method calculates instalments of provisional tax based on 105 percent of the prior year’s residual income tax liability or 110 percent of the year preceding the prior year depending on whether the taxpayer has filed their tax return for the prior year.

Example 1

Wooley Shearers Limited (Wooley) provides shearing services to farmers. The company has difficulty estimating its provisional tax for the year as it charges by the weight of the wool and the amount of income derived depends on the growing rate of the sheep. In the 2017 income year Wooley has residual income tax of $260,000. Wooley has filed its 2017 tax return prior to the first instalment of provisional tax and decides to pay its 2018 provisional tax using the standard method. This will require it to pay three instalments of $91,000, which it does on the respective dates.

Because of ideal wool-growing conditions, Wooley has a standout 2018 year and at the end of the year Wooley calculates its residual income tax as $390,000. This means that Wooley should have paid instalments of $130,000. Wooley will be charged UOMI on the difference between the instalments calculated by reference to their residual income tax and what they paid, being $39,000 ($130,000 - $91,000) for each instalment until the amount of the underlying tax and UOMI is paid.

New section 120KBB of the Tax Administration Act 1994 provides a new method for applying use of money interest for most standard method and some estimation method provisional taxpayers.

The effect of the changes is that when a taxpayer pays the required instalments of provisional tax (excluding the final instalment) based on the standard method amount, no UOMI will apply to any over- or underpayment of tax until the due date for the final instalment.

Example 2

Assuming the same facts for Wooley above, the new rules in section 120KBB will apply to Wooley because it paid its first two instalments based on the standard method on time, and assuming all the other requirements of section 120KBB are met, UOMI will still apply to Wooley because it has underpaid its tax at the final instalment date. However, it will only apply from that date on the difference between Wooley’s residual income tax for the year and the amount paid to the final instalment date.

This means UOMI will be charged on the difference between $390,000 and $273,000, being $117,000, from the final instalment date until the underlying tax and applicable UOMI is paid.

This means that a taxpayer who makes all their instalments (other than the final instalment) using the standard method and makes a final instalment which covers their residual income tax for the year will pay no UOMI for the year. Given the final instalment for provisional tax is some time after balance date it should be possible for taxpayers to determine with reasonable accuracy their tax liability for the year and avoid the application of UOMI by topping up any shortfall in tax paid by the final instalment.

Example 3

Wooley again uses the standard method in the 2019 income year and under that method is required to make 3 instalments of $136,500 ((105 percent of $390,000)/3). It makes the first two instalments on time but just before the due date for the third instalment Wooley calculates that it has had another spectacular year and its residual tax liability for the year is actually $650,000. This means it should have made instalments of $216,667. Wooley decides not to pay the final instalment based on the standard method amount but rather makes a payment based on its estimate of its final tax liability for the year. Wooley makes a payment of $377,000 on the due date for the final instalment.

When Wooley completes its tax return for the 2019 year it calculates its final tax liability for the year as $655,000. As Wooley has underpaid its tax for the 2019 income year it will be charged UOMI. Because Wooley has made all its instalments (other than the final instalment) using the standard method, and assuming all the other requirements of section 120KBB are complied with, Wooley will only be charged UOMI from the date of the final instalment until the tax and any UOMI is paid on the difference between Wooley’s residual income tax and the amount paid: $5,000 ($655,000 - 600,000).

Who can use the new rules?

A taxpayer must be an interest concession provisional taxpayer to use the new rules. This means they must be liable to pay provisional tax and:

- use one of the standard methods described in section RC 5(2) or (3) of the Income Tax Act 2007 for the tax year (commonly known as the “uplift” method); or

- use the estimation method described in section RC 5(5) but their payments of provisional tax on or before the instalment dates for the tax year other than the final instalment are not made under the estimation method and are equal to the amounts under the standard method.

Essentially this means the person either uses the standard method for all of their instalments or the standard method for all instalments except the final one, which they estimate. This allows a person to estimate an amount higher or lower than the standard uplift at the final instalment date to account for actual results during the year. Given the final instalment is after the end of the income year, a reasonable level of accuracy should be able to be applied to this final instalment to minimise any UOMI.

In addition, all provisional tax associates of the taxpayer must either be interest concession provisional taxpayers or use the GST ratio method for provisional tax, and there cannot be a provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement. Both definitions are discussed below.

What if a taxpayer does not pay the instalment due?

If a taxpayer does not pay the standard method instalments, UOMI will apply from the applicable instalment date on the lesser of:

- one-third[1] of the amount of residual income tax for the year less the amount paid; or

- the standard method instalment amount for the relevant instalment, less the amount paid.

This will also apply when a particular instalment is paid late.

The rule also differs from the previous rule, which charged UOMI on the difference between residual income tax and the amount paid for a particular instalment date.

Example 4

Thomas Water Finers Limited (TWFL) is a consulting firm that provides consulting services to the agricultural sector in the use of beavers to assist in water irrigation for farmers in drought affected areas. TWFL has a March balance date. As beavers are not yet permitted into New Zealand, a lot of TWFL’s time is spent lobbying the Government to permit the introduction of beavers to New Zealand. Once the Government permits introduction of the rodents to New Zealand TWFL expects its income earning to skyrocket as farmers see the benefits that using beavers as natural irrigators can have, based on experience in Nevada where beavers are used to provide natural irrigation.

In the 2018 income year TWFL had residual income tax liability of $55,000. Because of the uncertainty of the future of this innovative irrigation method, TWFL decides to use the standard method to pay provisional tax for the 2019 income year. It calculates it is required to make three instalments of $19,250 ((105%x$55,000)/3). TWFL pays its first instalment on time but between the first and second instalment dates the Government approves the introduction of beavers for irrigation schemes in New Zealand and TWFL’s workload increases dramatically. Because of this TWFL forget to make their second provisional tax instalment.

At the date of the third instalment, TWFL realise they have missed the second instalment and also calculate that because of the massive increase in consulting revenue their year-end tax liability is expected to be $1,250,000. TWFL want to minimise the impact of UOMI and so, on the final instalment date, the company makes a payment based on the estimate of its final tax liability of $1,231,239. This is made up of the tax owing ($1,230,750) and $489 for UOMI on the second instalment.

When it completes its tax return, TWFL calculates its final tax liability as $1,250,000, as it expected. Because TWFL did not make its second instalment on time it cannot use the concessionary rule in section 120KBB(2) for the missed instalment but instead must use the rule in section 120KBB(3) in relation to the missed instalment.

This will require the company to pay UOMI on the lesser of:

(a) 1 divided by the number of instalment dates for the income year multiplied by its residual income tax less the amount paid in relation to the instalment ((1/3x$1,250,000) -0 = $416,667); or

(b) the amount the company is liable to pay in accordance with the standard method for that particular instalment ($19,250).

The lesser of these amounts being (b), TWFL will be charged UOMI on $19,250 from the due date of the second instalment until the date that the tax and applicable UOMI is paid, which was the date of the third instalment ($489). TWFL may also be subject to late payment penalties.

Who is a provisional tax associate?

Under new section 120KBB all provisional tax associates of a taxpayer who wish to use the rules in section 120KBB are required to be an “interest concession provisional taxpayer” themselves or use the GST ratio method to calculate provisional tax. This is an anti-avoidance provision to stop related parties switching income between themselves to avoid the application of the UOMI rules.

Example 5

De Jong Limited (DJ) is a consulting firm owned by Jeff Jazzy. Jeff undertakes all the work for DJ as a shareholder-employee and payments from DJ to him are not subject to PAYE. In the 2016 year DJ has residual income tax of $70,000 as all the income was held in the company that year. Jeff had no residual income tax.

Over the next two years, assuming the same income level, but shifting it between DJ and Jeff, and alternating provisional tax calculation methods, no provisional tax is paid by either party, and there is no exposure to UOMI if the RIT is paid by the final instalment:

| Year | 2017 | 2018 | ||||

| Method | Prov amount | RIT | Method | Prov amount | RIT | |

| DJ | Estimate | Nil | Nil | Standard | Nil | $70,000 |

| Jazzy, Jeff | Not liable | N/A | $70,000 | Estimate | Nil | Nil |

The rule will only apply to persons who are provisional tax associates of the person wishing to use the rules within section 120KBB. A “provisional tax associate” of person A is defined as follows:

(i) If person A is a company, another company in the same wholly owned group of companies as person A is a “provisional tax associate”.

(ii) If person A is a company, another person that is associated with person A under section YB 3 of the Income Tax Act 2007, treating section YB 3 as requiring 50 percent voting interests and market value interests instead of 25 percent, and ignoring section YB 3(3) and (4) (commonly known as the tripartite test), is a “provisional tax associate”.

(iii) If person A is not a company or is a company acting as a trustee, another person that is associated with person A, treating section YB 3 of the Income Tax Act 2007 as requiring 50 percent voting interests and market value interests instead of 25 percent and also ignoring section YB 3(3) and (4) is a “provisional tax associate”.

This definition will essentially capture wholly owned group companies and those who have, directly or indirectly, a 50 percent or greater share in a company.

Example 6

Charger Limited (Charger) is owned equally and run by its two shareholders Macintyre and Alistair Craig. Both draw shareholder-employee salaries from the company from which no PAYE is deducted. Charger wishes to use the concessionary rules in section 120KBB. All provisional tax associates must also be “interest concession provisional taxpayers”.

As Macintyre and Alistair own 50 percent of the voting interest in Charger they will be required to be interest concession provisional taxpayers or use the GST ratio method to calculate provisional tax.

Example 7

Morrissey Limited (Morrissey) is a procurement consulting company owned equally by four university friends who are not related. All the owners draw shareholder-employee salaries from the company from which no PAYE is deducted. Morrissey wishes to use the concessionary rules in section 120KBB. All provisional tax associates must also be interest concession provisional taxpayers or use the GST ratio method.

As none of the four shareholders own 50 percent of the voting interest in Morrissey it can use the concessionary rules no matter what provisional tax method the shareholder-employees use.

Example 8

Coronet Super Bee Limited (CSBL) produces honey from a special breed of bee. It has two subsidiary companies, Hummer Limited (Hummer) that operates the hives and Bel Air Limited (Bel Air) that bottles the honey. Hummer is 100 percent owned by CSBL but Bel Air is only 50 percent owned by CSBL with the other 50 percent owned by Pacer Limited, another honey producer who is unrelated to CSBL.

Hummer would be required to be an interest concession taxpayer or use the GST ratio method to calculate its provisional tax for CSBL to use the concessionary rules in section 120KBB.

What is a provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement?

To be able to use the concessionary rules in section 120KBB there cannot be a provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement in relation to the person. This is defined in section 120KBB(4)(b) as being an arrangement involving the manipulation of one or more amounts of residual income tax, including a zero amount of residual income tax, with the purpose or effect of defeating the intent and application of the interest rules.

This is designed to capture the situation where related taxpayers manipulate income between entities to avoid the application of UOMI. It is expected that most of the opportunity to defeat the intention of the UOMI rules have been sufficiently dealt with in the requirement that provisional tax associates use the same provisional tax method. However, there may be some cases that will sit outside that provision where manipulation occurs.

Example 9

Assume the same facts for the Morrissey Limited (Morrissey) example. As above the shareholders of Morrissey are not caught by the provisional tax associate rule. During the 2018 income year Morrissey uses the standard method to calculate its provisional tax liability. In the 2017 year Morrissey used the last of its prior year tax losses, which resulted in a residual income tax liability of $20,000 for the company.

The shareholders meet and agree that for the 2018 year they will leave all the profits of the business within the company and will not take any shareholder salaries for the year. Morrissey pays its provisional tax instalments based on the standard uplift of $7,000 for each of the first two instalments. Prior to the third instalment it calculates its residual income tax for the year to be $240,000. It pays a final instalment on that estimated amount of $226,000. As it meets all the requirements of section 120KBB, UOMI will only apply from any unpaid tax at the final instalment.

When Morrissey completes its 2018 tax return it calculates its residual income tax as $240,000 and no UOMI is payable. No provisional tax is payable by the four shareholders for the 2018 year.

For the 2019 year the shareholders meet and agree that for the 2019 year they will pay out all the profits of Morrissey to the shareholders via shareholder salaries, which are not subject to PAYE. For the 2019 income year Morrissey estimates its provisional tax liability at zero. The shareholders are not liable for provisional tax. At the end of the 2019 income year the shareholders calculate that they each have residual income tax of $70,000 each. The shareholders are able to use the concessionary treatment in section 120KBB and pay the total amount of tax due by the due date for the final instalment.

For the 2020 year the shareholders meet and agree to reverse the 2019 position and leave all the income in the company and receive no shareholder salaries. The shareholders estimate their provisional tax liability at zero and Morrissey is not liable to pay provisional tax. Again the result is no provisional tax paid and no UOMI payable by the shareholders or the company. This essentially mirrors the situation described in the De Jong example above.

There are no commercial reasons for the switching of income between the parties other than to avoid the application of the UOMI rules. This situation is likely to be treated as a provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement and the rules in section 120KBB will not apply to any of the income years in question.

Example 10

Cowan Mattresses Limited (Cowan) has a residual income tax liability for the 2018 year of $100,000. It decides to use the standard method due to a volatile market in the mattress industry. Cowan’s 2019 provisional tax liability will be $105,000 with $35,000 being due at each instalment date.

The owner of Cowan, Matt, decides to set up another company called Cowan Mattresses (2019) Limited. This company has a slightly different shareholder structure and is not in a 100 percent wholly owned group with Cowan and is therefore not a provisional tax associate of Cowan Mattresses (2019) Limited.

Matt then makes an estimate of Cowan’s income tax liability to zero. All new mattress sales are put through Cowan Mattresses (2019) Limited during the 2019 year. At the time for the final instalment of provisional tax Cowan Mattresses (2019) Limited calculates that it has residual income tax of $130,000, which it pays on the date of the final instalment. Its 2019 tax return confirms that its residual income tax is $130,000 for the year and Cowan Mattresses (2019) Limited is charged no UOMI as it otherwise meets the requirements of section 120KBB. Cowen has no income for the year and has no residual income tax for the 2019 income year.

In the 2020 year Cowan Mattresses (2019) Limited decides to estimate its residual income tax as zero. Matt then books all mattress sales in Cowan for the 2020 income year. Again both entities pay no provisional tax for the year.

As there is no commercial reason for the structuring of the business in this way, and the effect of the structuring is that no UOMI is paid by the entities (along with no provisional tax), it is likely this situation would be considered a provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement and section 120KBB would not apply.

Can I make payments into a tax pool and still use the rules in section 120KBB?

Tax pooling is a mechanism to facilitate the payment of tax while reducing the impact of UOMI by allowing taxpayers to swap tax payments between those taxpayers who are overpaid and those who are underpaid.

The new rules in section 120KBB are related to the calculation of UOMI. The overlay of tax pooling does not change the application of the rules and taxpayers can still use tax pooling and take advantage of the new UOMI calculation rules as long as the criteria in section 120KBB are met.

Example 11

eWong Limited (eWong) is an advisor to e-commerce retailers, advising them on the security of payment methods. eWong is owned by Enia who has difficulty determining eWong’s tax liability for the year because of the uncertainty of income. She has previously used a tax pooling intermediary to facilitate the payment of eWong’s provisional tax liabilities. Enia sees value in using a tax pool as inevitably she finds that eWong’s provisional tax paid does not match its final tax liability no matter how hard she tries to estimate the earnings of the company for the year. Using the tax pool reduces her cost of UOMI when the estimate is understated and maximises credit UOMI when she ends up overpaying.

Enia sees advantages in using the new rules in section 120KBB but has an existing relationship with the tax pooling intermediary she uses and wishes to continue doing that.

For the 2018 year eWong’s residual income tax is $78,000, which means that if eWong wants to use the standard uplift method for its 2019 income year it will need to make three instalments of $27,300. It pays the first two instalments into the tax pooling intermediary on the due dates. On the date of the final instalment Enia calculates that eWong’s residual income tax for the 2019 income year is $100,000 so she decides to make a payment to the tax pool of the balancing amount of $45,400.

Within the time permitted to make transfers from the tax pool Enia requests that the pooling intermediary make transfers to the income tax account of eWong Limited of $27,300 at the first and second provisional tax dates and $45,400 on the final instalment date.

Assuming eWong meets all the other requirements of section 120KBB eWong will not be charged any UOMI as it has paid its tax liability for the year by the third instalment and has made the required payments under the standard method for the first two instalments.

Does credit UOMI apply to overpayments?

The concessionary rules contained in section 120KBB reduce the impact of UOMI on taxpayers by delaying the impact of UOMI until the final instalment date, which is after the end of the income year.

To be consistent with that, no UOMI is payable by Inland Revenue from the date of the final instalment. New section 120VC specifically provides for this. Taxpayers who use the concessionary rules in section 120KBB will have no credit interest paid to them in respect of overpayments until the date of the final instalment.

Example 12

Mack Limited is a manufacturer of raincoats. Mack has historically had a very seasonal business in that it tends to sell more raincoats during the winter months but due to climate change, the demand for raincoats is extremely unpredictable, which makes estimating the income of the company very difficult.

Mack has been using the standard method as the owner, Steve, finds it is the best estimation of income that he can make because of this unpredictability. However, even using the standard method Steve often finds that Mack ends up paying or receiving UOMI because of its residual income tax not matching with the standard method payments. Steve thinks the changes to section 120KBB will help Mack as it will ensure there is no exposure to UOMI.

In the 2017 year Mack has residual income tax of $847,000. It has not filed its 2018 return as yet so calculates its 2019 provisional tax based on 110 percent of the 2017 residual income tax. This will mean that Mack must make three instalments of $310,567 under the standard uplift.

Mack makes the first two instalments on that basis on time and when it gets to the third instalment Steve has a good idea of what the final residual income tax for Mack will be for the year. Unfortunately Mack has not had a good year, with rainfall at an all-time low. Steve calculates the residual income tax for Mack at the final instalment date to be $250,000. This means that Mack has overpaid its provisional tax for the year. At the final instalment date Mack estimates its provisional tax liability to be $250,000. It also requests a refund of the overpaid provisional tax from Inland Revenue, which it receives two months after the final instalment date.

When Mack files its 2019 income tax return the final residual income tax liability is $250,000. It is assumed that Mack meets all the other requirements of section 120KBB. Because Mack paid its total residual income tax by the final instalment date, no UOMI would be payable by Mack. In addition, although to the third instalment date Mack has overpaid its tax for the year, it will only receive credit UOMI from the final instalment date until the date the amount of the overpayment is refunded (that is, two months after the final instalment date).

Safe harbour from use-of-money interest

Amendments have been made that modify the existing safe harbour from UOMI. The changes increase the safe harbour from $50,000 to $60,000 of residual income tax and extend the safe harbour to non-individual taxpayers.

Background

Section 120KE of the Tax Administration Act 1994 contains a safe harbour for taxpayers from the application of UOMI. Under the previous rules, to qualify for the safe harbour, the taxpayer had to comply with the following requirements:

- be a natural person, other than in their capacity as a trustee;

- have residual income tax less than $50,000 for the tax year;

- not have estimated their residual income tax under section RC 7 of the Income Tax Act 2007;

- not have used a GST ratio under section RC 8 in the tax year to determine their provisional tax payable for the tax year; and

- not at any time in the tax year held an RWT exemption certificate under section 32I of the tax Administration Act 1994.

The taxpayer’s residual income tax would then be due and payable in one instalment on their terminal tax date. This means no UOMI would be payable by the taxpayer for the tax year notwithstanding they may have underpaid their liability at one or more instalments.

Changes in the new Act modify this rule.

Key features

The modifications to the current safe harbour rule:

- increase the threshold to use the safe harbour for a taxpayer’s residual income tax from $50,000 to $60,000;

- extend the safe harbour to non-individual taxpayers;

- ensure that taxpayers using the safe harbour have paid the instalments required;

- remove the current requirement that the taxpayer cannot use the safe harbour when they have an RWT exemption certificate issued under section 32I; and

- introduce a new anti-avoidance provision to the safe harbour.

The safe harbour rule is designed to alleviate the impact of UOMI for those taxpayers who have relatively small amounts of residual income tax. This concession has previously only been available to natural persons. The changes extend the safe harbour to non-individuals and increase the threshold to residual income tax of less than $60,000. To prevent non-individuals from manipulating incomes between related parties, a new anti-avoidance provision has been introduced to protect against gaming of the safe harbour.

There has also been a consequential amendment to the definition of “initial provisional taxpayer” in section YA 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007 to reflect this change.

Application date

The amendments to the safe harbour rule in section 120KE(1) apply for the 2017–18 and later income years.

Detailed analysis

Section 110 of the new Act modifies the application of the safe harbour by modifying section 120KE(1) of the Tax Administration Act 1994.

It replaces section 120KE(1)(a), removing the requirement for the taxpayer to be a natural person but requiring that the taxpayer to make all instalments required under sections RC 3(3), RC 9 and RC 10 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

Subsection 110(2) replaces $50,000 with $60,000 in section 120KE(1)(b) increasing the threshold for residual income tax to use the safe harbour from $50,000 to $60,000.

Subsection 110(3) introduces the anti-avoidance provision which requires that there is no provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement in relation to the taxpayer.

A provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement is defined in new section 120KBB of the Tax Administration Act as an arrangement involving the manipulation of one or more amounts of residual income tax, including a zero amount of residual income tax, with the purpose or effect of defeating the intent and application of the interest rules within the Tax Administration Act.

Subsection 110(3) also removes the current requirement in section 120KE(1)(e) that restricts taxpayers who have a RWT certificate of exemption issued under section 32I from using the safe harbour.

When the safe harbour applies

The amended safe harbour rule in section 120KE(1) provides that a provisional taxpayer’s residual income tax for a tax year is due and payable in one instalment on their terminal tax date if:

- they have paid all instalments under one of the standard methods described in section RC 5(2) or (3) of the Income Tax Act 2007 on or before the instalment dates in accordance with sections RC 9 and RC 10 or they have no obligation to pay provisional tax under section RC 3(3);

- their residual income tax is less than $60,000 for the tax year;

- they have not estimated their residual income tax under section RC 7 of the Income Tax Act 2007 for the tax year;

- they have not used a GST ratio under section RC 8 of that Act in the tax year to determine the amount of provisional tax payable for the year; and

- there is no provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement in relation to the person.

Example 13

Leroy is a provisional taxpayer for the 2018 income year who uses the standard method. He is required to make three instalments of $10,000 during the year which he does on the applicable due dates. When Leroy completes his tax return he discovers that his residual income tax for the year is $57,000. He has underpaid his provisional tax for the year. However, because Leroy has paid all three instalments on the due dates, his residual income tax is less than $60,000, he has not estimated or used the GST ratio method and there is no provisional tax avoidance arrangement in relation to Leroy, section 120KE (1) will deem his residual income tax to be due and payable in one instalment on his terminal tax date. He will not have any UOMI exposure until that date.

Example 14

Shoshanna is a provisional taxpayer for the 2018 income year. Under the standard method she is required to make three instalments of $10,000 on 28 August 2017, 15 January 2018 and 7 May 2018. She makes the following payments during the year:

28 August 2017 $9,000

15 January 2018 $8,000

7 May 201 8 $28,000

When she completes her tax return for the year Shoshanna calculates she has a residual income tax of $45,000.

Because Shoshanna did not make the required payments under the standard method on the instalment dates she is not able to use the safe harbour and will be subject to UOMI.

Example 15

Tanks-R-Us Limited is a small business that manufactures and sells earthquake water storage tanks to consumers. It was not liable for provisional tax in the 2016–17 year as it had tax losses for the year. Because of an upturn in demand for tanks in the 2017–18 income year, when Tanks-R-Us completes its 2018 tax return it calculates it has a residual income tax of $59,500. Tanks-R-Us is deemed to be a provisional taxpayer for the 2018 tax year under section RC 3. However, because the company has residual income tax of less than $60,000, and it was not required to make any provisional tax instalments for the year under section RC 3(3), it will fall within the safe harbour and its residual income tax will be due and payable on its terminal tax date with no exposure to UOMI until that date.

Provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement

A provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement is defined in section 120KBB(4) of the Tax Administration Act 1994 as an arrangement involving the manipulation of one or more amounts of residual income tax, including a zero amount of residual income tax, with the purpose or effect of defeating the intent and application of the interest rules in Part 7 of the Tax Administration Act 1994.

It is intended that this provision will apply to the most egregious of cases where a taxpayer has manipulated the flow of income to avoid application of the interest rules and take advantage of the safe harbour. It will not apply when normal commercial transactions result in taxpayers being within the safe harbour concession.

Example 16

Aroha works as a self-employed computer consultant. She also owns 100 percent of a company that undertakes interior design for domestic clients, Inside Out Limited. Aroha operates the interior design business in her spare time, usually on weekends.

Both Aroha and Inside Out Limited make provisional tax payments using the standard method. For the 2017–18 income year both taxpayers make the required standard uplift instalments on the applicable due dates. When they file their tax returns Aroha has $58,700 and Inside Out Limited $59,670 of residual income tax. These two operations are clearly run separately and there has been no manipulation of income so there will be no provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement and both entities will be within the safe harbour.

Example 17

Savannah is a self-employed building contractor who specialises in installing swimming pools. Year on year her residual income tax can fluctuate from $57,000 to $110,000. She notes the changes to the safe harbour rules have extended these rules to non-individuals. Savannah looks to take advantage of these rules and decides to set up a company, Savvy Pools Limited. During the year she bills clients from herself and from the company so that the income from the business is split between the company and herself.

At the end of the income year Savannah and Savvy Pools Limited file their tax returns and they have residual income tax of $59,999 and $59,999 respectively. In this case there is no commercial reason for the income from the same income earning activity to be split in this manner other than to take advantage of the safe harbour concession.

It is likely that Savannah and Savvy Pools Limited will be considered to have a provisional tax avoidance arrangement and the safe harbour will not apply to either taxpayer.

Example 18

Jessie James owns a railroad consulting business JJ Rail Limited (JJRL). JJRL uses the standard uplift method to pay its provisional tax. It generally has residual tax of around $40,000. Part way through the 2017–18 income year JJRL realises it is having a spectacular year and is likely to have residual income tax of $100,000. JJRL decides to set up a subsidiary company JJ Railroads Limited (JJRRL). It commences billing clients through JJRRL partway through the year. At the end of the income year JJRL, which has paid all its required provisional tax instalments on time throughout the year, calculates it residual income tax as $59,000. JJRRL calculates its residual income tax as $50,000. All the other criteria of section 120KE(1) are satisfied, and prima facie, both JJRL and JJRRL will fall within the safe harbour.

However, because the setting up of the new subsidiary and the transfer of income stream from one entity to the other is for no other apparent commercial reason it is likely that both companies have a provisional tax interest avoidance arrangement and the safe harbour will not apply.

Allowing contractors to elect their own withholding rate

An amendment has been made which will allow contractors who are subject to the schedular payment rules to elect their own withholding rate without having to apply to Inland Revenue for a special tax code.

Background

Previously, a contractor subject to the schedular payment rules was subject to a flat rate of withholding. This rate would often not accurately match the contractor’s actual income tax liability. Contractors could obtain a special tax code to alter their rate, but the process could increase compliance costs for them, requiring them to apply to Inland Revenue and supply supporting information.

Key features

A new rule allows contractors who are subject to the schedular payment rules to elect their own withholding rate without having to apply to Inland Revenue for a special tax code.

There will be some situations when a contractor will not be able to elect their own rate. These include:

- when a contractor has not provided their name and IRD number, a “no-notification rate” applies of 20% for non-resident companies and 45% for other contractors; and

- when a contractor has not met a liability under an Inland Revenue Act, the Commissioner can prescribe a rate of withholding.

A minimum rate of withholding applies to contractors. For non-resident contractors and contractors with temporary work visas, this minimum rate is 15%, for all other contractors the minimum rate is 10%.

If a contractor has changed their rate twice in a 12-month period, they will require the consent of the payer to any further changes.

If a contractor has not selected a rate, a “standard rate” applies. This standard rate is the relevant rate listed in schedule 4 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

Application date

The amendment comes into force on 1 April 2017 and applies to payments made from 1 April 2017, regardless of when the services relating to the payment were performed.

Detailed analysis

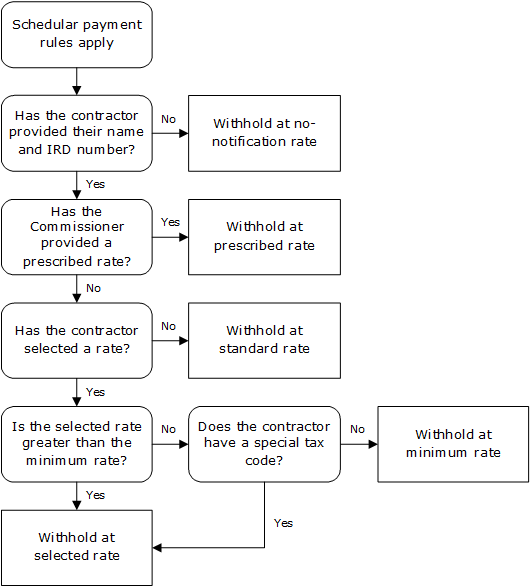

New section RD 10B of the Income Tax Act 2007 sets new rules for what rates apply for contractors subject to the schedular payment rules. The flowchart below summarises these rules:

(Full size | SVG source)

Overview of different rate types

| Description | Rate | |

| Elected rate | Chosen by the payee. | 10% – 100% |

| Special rate | Payee can request from Commissioner. | Only necessary if the payee wants a rate lower than 10% (or 15% as above) |

| No notification rate | When the payee does not provide name or IRD number to the payer. | 20% for non-resident companies |

| Prescribed rate | Set by Commissioner when the payee has not met a liability under the Inland Revenue Acts. | Cannot exceed 50% |

| Non-resident entertainer rate | This rate must be used by non-resident entertainers. | 20% |

| Standard rate | The rate for the activity or arrangement set out in schedule 4, which will apply if none of the rates set out above apply. | Vary between 10.5% and 33% depending on the type of activity or arrangement |

Elected rate

New section RD 10B(3)(a) of the Income Tax Act 2007 and section 24LB of the Tax Administration Act 1994 provide that contractors subject to the schedular payment rules may elect the withholding rate that is to apply to payments to them.

To elect a rate of withholding, the contractor must notify the person making the payment of the rate to apply and this notification must be made in a form approved by the Commissioner. The selected rate continues to apply until the contractor makes a new election or until the contractor is no longer able to elect a rate due to a prescribed rate notice being given or otherwise.

Minimum rate

To address the risk that contractors may attempt to defer or avoid paying their tax by choosing an artificially low withholding rate, section 24LB(2) provides that contractors must elect a rate of withholding that is not less than the minimum rate.

For non-resident contractors and contractors who are holders of temporary entry class visas, the minimum rate is 15%. For all other contractors, the minimum rate is 10%.

Special tax rate

A contractor may have a rate lower than the minimum if they obtain a special tax rate certificate under section 24N of the Tax Administration Act 1994.

Repeatedly changing withholding rates

If a contractor has previously elected a withholding rate twice in a 12-month period to the same payer, they require the consent of the schedular payer to make any further changes in their withholding rate.

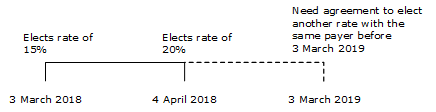

Example 19

(Full size | SVG source)

On 3 March 2018 Caroline starts work as a building contractor for Small Builders Ltd. Payments from Small Builders to Caroline are subject to the schedular payment rules and Caroline initially selects a withholding rate of 15%.

On 4 April 2018, Caroline wishes to change her withholding rate and notifies Small Builders that she wishes to have a withholding rate of 20% apply to her. Caroline does not require the consent of Small Builders to this change as she has only elected a withholding rate once within the last 12 months. However, if Caroline wishes to make any further changes to her withholding rate for payments made by Small Builders up till 3 April 2019, she will require the consent of Small Builders.

On 5 August 2018, Caroline starts work for Large Builders Ltd. Caroline can elect a new withholding rate without the consent of Large Builders Ltd. as she has not previously elected a withholding rate with Large Builders.

No notification rate

Section RD 10B(2) provides that when a contractor does not give their name and IRD number to their payer, payments to them must have tax deducted at the “no notification rate”. The no notification rate is 20% for non-resident companies, and 45% for all other contractors.

This replaces the current “no notification” rate for schedular payments in section RD 18 of the Income Tax Act 2007. This is intended to provide a simpler “no notification” rate for schedular payments that is aligned with the rate that applies to employees.

Prescribed rate

Section RD 10B(4) of the Income Tax Act 2007 and section 24LC of the Tax Administration Act 1994 provide that when a contractor has not met a liability under the Inland Revenue Acts the Commissioner has the ability to prescribe a withholding rate.

The process for the prescribed rate is similar to the one for deduction notices under section 157 of the Tax Administration Act 1994, and requires a notice to be provided to the payer or the contractor that a different rate should be applied. If a notice is provided to the payer, the payee must also be provided a notice unless, after making reasonable enquiries, the Commissioner does not have a valid address for the contractor.

Under the amendments the Commissioner can require two different types of prescribed rate deductions. These are:

- standard schedular payment deductions under the ordinary PAYE rules (which provide PAYE tax credits for the contractor); or

- additional deductions, which are used to meet the contractor’s tax debts or other liabilities.

The additional deductions would generally be required to be recorded on a separate line in the employer monthly schedule and under a different tax code. This is similar to the way additional deductions are currently done for student loans. When additional deductions are paid in this way, the initial late payment penalties charged on the original debt are not applied.

Revocation of prescribed rate

The Commissioner can rescind a prescribed rate at any time.

A taxpayer can also apply to have the prescribed rate notice rescinded by the Commissioner.

For prescribed rates relating to standard schedular payment deductions, the Commissioner must revoke the prescribed rate on application, if she is satisfied that all liabilities under the Inland Revenue Acts have been met and she is reasonably satisfied that the contractor will be likely to meet their liabilities in the future.

For additional deductions to meet the contractor’s tax debts or other liabilities, the Commissioner must revoke the prescribed rate on application, if she is satisfied that the contractor has paid all tax due and payable.

The Commissioner does not intend to use this prescribed rate notice to require additional deductions to meet a contractor’s other tax debts until schedular payments are administered in Inland Revenue’s new computer system (START).

Example 20

Ben is a building contractor. He earns $120,000 each year from his building contracts with several major building companies. Ben elects a withholding rate of 10% and $12,000 is withheld from him for the year.

Ben predominantly provides labour services and has minimal deductions. His end-of-year tax liability is $30,000 and so Ben has a terminal tax bill of $18,000. Ben does not pay his terminal tax bill and so ends up with a tax debt.

The Commissioner prescribes a new rate of withholding to Ben and his payers. This new rate is:

- 25% under the standard schedular payment code (WT). Ben receives PAYE credits for these amounts and these amounts are intended to ensure that Ben does not have an end-of-year income tax liability and further tax bills; and

- an additional 15% under a new tax code and recorded on a new line in the employer monthly schedule. Amounts withheld under this code are used to pay Ben’s tax debt for the previous year.

Standard rates

If a contractor does not elect a rate of withholding under section 24LB of the Tax Administration Act 1994, section RD 10B(3)(b) of the Income Tax Act 2007 provides that the standard rate of withholding applies to them.

The standard rate is the relevant rate set out in schedule 4 of the Income Tax Act 2007. For contractors working for labour-hire firms and those under voluntary withholding agreements the standard rate is 20%.

For other contractors the standard rate in schedule 4 is the same as the rate that currently applies to those payments. This means that if a contractor that was previously subject to the schedular payment rules does not elect a different withholding rate when the amendments come into force, their withholding rate remains unchanged.

Non-resident entertainers

The amendments do not apply to non-resident entertainers. Non-resident entertainers will continue to have a flat withholding rate of 20%. These entertainers can continue to have withholding treated as a final tax and will not have to file returns.

Extending withholding to labour-hire firm contractors

Amendments have been made which extend the schedular payment rules to contractors that work for labour-hire firms.

Background

Over the last two decades there has been large growth in the labour-hire firm industry. The new rules better reflect changes within the industry and update the rules more generally for contractors working for this industry.

Labour-hire firms provide workers to perform services to clients, either as employees or contractors. The previous withholding rules did not generally apply to contractors engaged by labour-hire firms. This meant these contractors were required to manage their own tax obligations, including provisional tax. It also meant that contractors had opportunities for non-compliance (whether deliberate or accidental).

In addition, using a company structure has become increasingly popular with contractors. Payments to companies are generally not subject to withholding tax under the schedular payment rules.

Key features

The amendments add payments by labour-hire firms to their contractors to the list of payments that are subject to the schedular payment rules.

As a result, labour-hire firms will be required to withhold from all payments made to their contractors that work as part of their labour-hire business. They will be required to withhold at the relevant rate as described under the amendments outlined in “Allowing contractors to elect their own withholding rate”.

Labour-hire firms will also have an obligation to deduct withholding tax when they make payments to companies used by contractors. Labour-hire firm contractors who are resident in New Zealand will not be eligible to receive certificates of exemption from withholding.

A labour-hire firm is defined as “a person which has as one of its main activities the business of arranging for a person to perform work or services directly for clients of the entity”.

Application dates

The amendments come into force on 1 April 2017.

If a labour-hire firm is unable to have systems in place for reasonably cost-effective compliance with the new rules before 1 April 2017, the amendments apply to the earliest of:

- 1 July 2017; or

- the date on which the labour-hire firm has systems in place for reasonably cost-effective compliance with the labour-hire firm rules.

Detailed analysis

The amendments insert Part J to schedule 4 of the Income Tax Act 2007, which adds payments made by labour-hire firms to contractors under a “labour-hire arrangement” to the schedular payment rules.

Under Part J, payments are covered by the schedular payment rules when:

1. The payment is made under a labour-hire arrangement (as defined).

2. One of the main activities of the person making the payment is providing labour-hire arrangements (that is, the labour-hire arrangement is not incidental to the main business of the person).

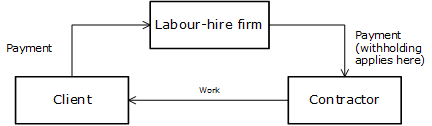

1. The payment is made under a labour-hire arrangement

(Full size | SVG source)

A labour-hire arrangement is an arrangement which in whole or part involves the performance of work or services by a person (the payer) directly for the client of the payer, or directly for a client of another person. The payer receives payment from the client and pays the worker.

Arranging for a person to perform work or services directly for clients means that there is an agreement to provide a worker to the client, who will then provide their services at the general direction of the client. This does not include a contract in which the parties agree to deliver a given result or outcome. For example, if a contract provided for Firm A to make available some painters to a building company to work for them for a period of time, and the painters work at the general instruction of the building company, then Firm A would be arranging for a person to perform work or services.

In contrast, if a contract provided for a painting company to paint houses for a building company, and the painting company contracted some labourers to work for it in completing the service, the contract between the painting company and building company would be a contract to produce a given result (the painted houses) rather than a contract arranging for a person to “perform work or services directly for clients”.

Directly for a client of another person

A labour-hire arrangement also includes situations when there are chains of labour-hire firms involved or when a labour-hire firm provides a worker to a sub-client of the labour-hire firm. This can happen if a labour-hire firm arranges for another labour-hire firm to provide workers for their client.

2. One of the main activities of the payer is providing labour-hire arrangements (that is, the labour-hire arrangement is not incidental to the main business of the entity)

The amendment only applies when one of the main activities of the entity making the payment is providing labour-hire services. This means that withholding under the amendment only applies if the entity is carrying on a labour-hire business. It is not necessary for the labour-hire activities to be the sole business, or even the main business of the payer. However, a merely incidental business is not sufficient to require withholding.

For something to be one of the main activities of the business requires the activity to be more than incidental to the other activities of the firm. For example, a wedding planner may arrange for persons to perform makeup, or other services directly for clients, but because this is incidental to the main activity of the planner, it will not make the wedding planner a labour-hire firm.

A business can have more than one main activity. For example, a labour-hire firm may have main activities of providing workers directly, as well as providing direct contracting work. The key question to ask is whether arranging to provide workers directly is being done in a business of its own right, or whether it is merely a requirement or incidental activity of another activity of the business.

The amendment is similar to Australia’s Pay-As-You-Go withholding rules.

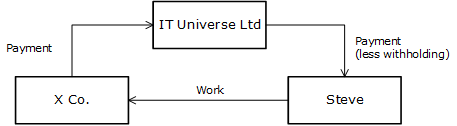

Example 21

IT Universe Ltd provides contractors to other businesses to help with their IT projects. X Co. asks IT Universe Ltd for IT contractors to help with an upgrade of its systems. IT Universe Ltd provides one of their contractors (Steve, a New Zealand resident) to assist X Co. Steve works at the general direction of IT Universe Ltd.

(Full size | SVG source)

IT Universe Ltd is arranging for a worker (Steve) to provide work directly for their client (X Co.). As a result, they are in a labour-hire arrangement with Steve and X Co. and this arrangement is part of their labour-hire business. IT Universe Ltd is required to withhold tax from any payments to Steve. The rate will be the applicable rate as set out in the earlier section “Allowing contractors to elect their own withholding rate”. If it does not specify a rate then the standard rate for labour-hire firm contractors of 20% will apply.

Example 22

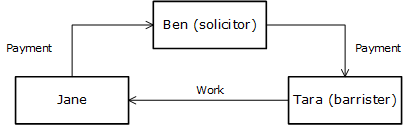

Ben is Jane’s solicitor. Jane is engaged in litigation and requires a barrister to represent her in court. For this purpose, Ben instructs Tara and pays Tara on Jane’s behalf.

(Full size | SVG source)

Ben is arranging for a contractor (Tara) to provide work directly for their client (Jane). However, Ben is not required to withhold from these payments because arranging for people to work for his clients is not one of his main activities. The payment is incidental to his business of providing legal services.

Example 23

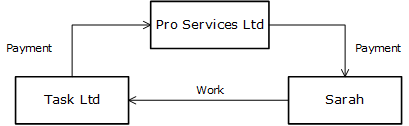

Pro Services Ltd is a professional services firm whose core business is providing consulting and advisory services to clients. Pro Services Ltd engages many of its staff as contractors.

Sarah is one of these contractors whose work has impressed Task Ltd who is one of the clients of Pro Services Ltd. Task Ltd asks Pro Services Ltd for Sarah to work for them for six months to assist with one of their projects. Under this arrangement, Sarah will work at the general direction of Task Ltd.

(Full size | SVG source)

Pro Services Ltd is arranging for a contractor (Sarah) to perform services directly for the client of Pro Services Ltd (Task Ltd). As a result, this is a labour-hire arrangement.

However, entering into labour-hire arrangements is not one of the main activities of Pro Services Ltd. Instead this is a one-off transaction that is being done incidental to Pro Services Ltd’s core business. Pro Services Ltd did not advertise to provide this service and does not expect to enter into similar arrangements in the future or plan to do so as a business in its own right.

Example 24

Pro Services Ltd found the previous arrangement with Task Ltd to be a success, and starts offering similar services to more clients and advertising this service on its website.

Pro Services Ltd is now providing labour-hire arrangements as a business in its own right. As a result, it can be considered to be one of the main activities of Pro Services Ltd, and payments made to Sarah and other contractors as part of this labour-hire business are subject to the schedular payment rules.

Example 25

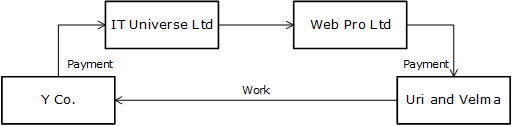

Y Co. asks IT Universe Ltd for web designers to help them build a new website. IT Universe agrees to provide a number of web designers to Y Co. but is unable to find enough suitable people.

IT Universe Ltd goes to Web Pro Ltd (another labour-hire firm) and arranges for some of Web Pro’s contractors (Uri and Velma) to perform work for Y Co.

(Full size | SVG source)

Web Pro Ltd is arranging for contractors (Uri and Velma) to perform work directly for the client (Y Co.) of another entity (IT Universe Ltd). As a result, they are in a labour-hire arrangement and this arrangement is part of their labour-hire business. Web Pro Ltd is therefore required to withhold from any payments it makes to Uri or Velma.

Example 26

Paul is a builder and contracts to build a house for Susan. He subcontracts another contractor, Bruce, to do the plumbing work for the house. Paul is not required to withhold from payments to Bruce because he is not arranging for workers to perform work directly for clients. Instead Paul is arranging to produce a specified output for Susan (building a house).

Company exception

The amendments provide that the general exception to the schedular payment rules for companies will not apply to payments under labour-hire arrangements.

That means labour-hire firms will be required to withhold from payments in the circumstances outlined above regardless of the type of legal entity the payments are made to. This applies regardless of whether the payment is also covered by the schedular payment rules due to it being a payment of a type described in another part of schedule 4 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

A company that finds it is being over-withheld as a result of this, can apply for a special tax code to reduce its withholding rate below the minimum rate. This can include applying for a withholding rate of 0%.

Example 27

As in the earlier example, IT Universe Ltd. has agreed to provide web designers for Y Co. IT Universe arranges for Web Pro Ltd to provide workers for Y Co.

IT Universe is arranging workers to provide work directly to clients. As a result, they are in a labour-hire arrangement and this labour-hire arrangement is part of their labour-hire business. As a result IT Universe Ltd is required to withhold from any payment made to Web Pro.

Web Pro may apply for a special tax code to reduce its rate of withholding (including applying for a rate of 0%).

Associated party transactions

If the payer and payee are associated persons under sections YB 2 (Two companies) or YB 3 (A company and a person other than a company), the payer may choose not to treat the payment as being subject to withholding under the labour-hire firm rules.

This choice is intended to prevent overreach in the rules where the rules could apply to payments that are effectively made between entities that are part of the same business. In these situations, it is considered that the requirement to withhold would impose additional compliance costs for little benefit.

Example 28

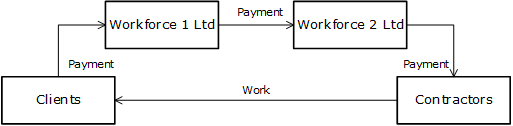

Workforce 1 Ltd is a labour-hire firm that provides workers to perform work directly for clients. As part of its business structure Workforce 1 Ltd chooses to have its sales, marketing and client-facing side of the business managed by Workforce 1 Ltd while its staff management is handled by Workforce 2 Ltd. Workforce 1 Ltd and Workforce 2 Ltd are part of a wholly owned group.

Workforce 1 Ltd. pays Workforce 2 Ltd part of the fees received by clients in order to pay their contractors.

(Full size | SVG source)

Workforce 1 Ltd and Workforce 2 Ltd are wholly owned companies and as a result are associated under section YB 2. As a result, Workforce 1 Ltd may choose to treat payments made to Workforce 2 Ltd as not subject to withholding under the labour-hire firm rules.

Workforce 2 Ltd will still need to withhold from payments it makes to its contractors.

Certificates of exemption

Under the amendments, contractors that are resident in New Zealand and are working for labour-hire firms cannot obtain certificates of exemption to exempt themselves from the schedular payment rules. These contractors cannot obtain certificates of exemption even if the payment is covered by the schedular payment rules by virtue of another part of schedule 4 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

These contractors may still apply for a special tax rate if withholding is inappropriate, which includes being able to apply for a 0% rate. This means that all resident contractors working for labour-hire firms must have payments to them recorded on the Employer Monthly Schedule even if a 0% rate of withholding applies to them.

Non-resident contractors who work for labour-hire firms may continue to use certificates of exemption.

Example 29

Agriculture Angels is a labour-hire firm that provides fruit pickers to farmers. The fruit pickers are engaged as contractors by Agriculture Angels and payments to them are covered by the schedular payment rules under the new labour-hire firm rules (Part J of schedule 4) as well as those for worker services relating to primary production (Part C of schedule 4).

The contractors of Agriculture Angels cannot utilise certificates of exemption from withholding. Instead, these contractors will need to apply for special tax rates of 0% if withholding is not appropriate for them.

Transitional rule

To allow an easier transition to special tax rates for contractors working for labour-hire firms, a transitional rule applies for these contractors whose certificates of exemption are no longer valid as a result of the amendments. Under the transitional rule, contractors who have a certificate of exemption before 1 April 2017 may have the certificate treated as a special tax rate of 0% till 1 April 2018, if the certificate of exemption is invalid as a result of the amendments.

Voluntary withholding agreements

Amendments have been made which will allow contractors not covered by the schedular payment rules to opt in to the rules with the consent of their payer.

Background

Currently contractors not covered by the schedular payment rules are not able to have tax withheld on a payday basis. Many of these contractors may prefer to pay their tax through the schedular payment rules.

Key features

Contractors that are not subject to the schedular payment rules will be able to enter into a voluntary withholding agreement with their payers. If an agreement is entered into, the contractor becomes subject to the schedular payment rules and the payer will be required to withhold from payments made to them.

The proposed amendments insert Part W into schedule 4 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

Part W sets out that a payment to a person is a schedular payment when:

- there is no obligation to withhold from the payment under the Income Tax Act 2007 or the Tax Administration Act 1994; and

- the contractor and their payer have agreed to treat the payment as a voluntary schedular payment, and have recorded their agreement in a document.

If these two criteria apply, the schedular payment rules apply and the payer is required to withhold from the contractor at the rate selected by the contractor (as per the amendments outlined in “Allowing contractors to elect their own withholding rate”).

This can apply to payments made to companies as well as payments such as expense reimbursements,[2] which previously have not attracted withholding tax so long as the parties have entered into an agreement for withholding to apply.

Determining whether there is a valid agreement is based on standard contract law principles and requires there to be offer and acceptance, intention to create legal relations and objective evidence of agreement (which will usually be satisfied if the requirement that the agreement must be in a document has been met).

A document can be a memorandum, email, letter, or formal contract between the parties. As long as there is sufficient written evidence that there has been a required agreement between the parties (which can be either electronic or in hardcopy), this requirement will be met.

Payments covered by voluntary withholding agreements are excluded from the definition of “employer and employee” for the purpose of the FBT rules. This means that fringe benefit tax does not apply when fringe benefits are provided to contractors under voluntary withholding agreements.

Application date

The amendments will come into force on 1 April 2017.

Use-of-money interest and transfers of tax

Amendments have been made to sections 120C, 173L, 173M and 173S of the Tax Administration Act 1994 to prevent taxpayers from transferring tax to an earlier period that exceeds the amount in debt or in dispute in that period, and to clarify when UOMI starts and when a transfer takes effect for GST refunds and GST overpayments.

Background

Taxpayers are able to transfer tax credits to other tax periods, tax types or taxpayers.

Currently, taxpayers are able to transfer amounts that exceed the amounts owing in previous periods. When this happens they are paid UOMI from an earlier date than if they had not moved the money.

The Tax Administration Act 1994 does not distinguish between a GST refund, which occurs when GST inputs/expenses exceed GST outputs/sales, and a GST overpayment, which occurs when a taxpayer overpays their GST liability. As both actions result in a credit, it can be argued that a GST overpayment constitutes a refund, and is therefore eligible for the transfer date applicable to GST refunds, which is earlier than the transfer date applicable to overpayments. The date of transfer affects when UOMI on a previous overpayment stops being charged. Therefore a taxpayer transferring an overpayment of GST to settle a debt in a previous period will pay less UOMI to Inland Revenue than was intended because the payment will be transferred at the earlier refund date, rather than the date at which they made the overpayment.

Key features

Sections 173L, 173M and 173S of the Tax Administration Act 1994 have been amended to limit transfers of tax within a taxpayer’s accounts, transfers of tax to another taxpayer and transfers of interest on overpaid tax to the total of (for the requested transfer period at the chosen transfer date):

- the debt owing by the relevant taxpayer;

- the taxpayer’s deferrable tax;

- the amount under a notice of proposed adjustment; and

- any amount agreed with the Commissioner.

Section 173L has also been amended to clarify when a transfer will take effect for GST refunds and GST overpayments.

Section 120C has been amended to clarify the date that UOMI will start for GST refunds and GST overpayments.

Application date

The amendments came into force on 5 February 2017.

Amending the rules for new and increased assessments by the Commissioner

Section 142A of the Tax Administration Act 1994 has been amended to enable the Commissioner to offset any credits or refunds the taxpayer has against the taxpayer’s tax liability arising from a new or increased assessment by the Commissioner.

Sections 139B, 139BA and 142B have been amended to ensure late payment penalties and shortfall penalties continue to be correctly applied following the amendment to section 142A.

Background

Generally, when the Commissioner makes a new assessment, or increases an assessment, a new due date is set for the payment of the resulting tax. This allows the taxpayer time for payment before late payment penalties, which accrue from the day after the new due date, are imposed. Use-of-money interest continues to apply from the day after the original due date for payment of the tax.

When a new due date is set, any credits or refunds available before the new due date are generally refunded to the taxpayer as they cannot be offset against the upcoming liability as it is not yet “due”. The taxpayer then needs to make a payment to Inland Revenue by the new due date, shortly after receiving the refund.

Inland Revenue’s FIRST computer system was unable to give additional time before the imposition of late payment penalties without setting a new due date. Its new system, START, is able to use the original due date for payment but still allow time for payment before the imposition of late payment penalties.

Key features

Section 142A of the Tax Administration Act 1994 has been amended so that a new due date for payment is not set following a new or increased assessment by the Commissioner. This ensures that any credits or refunds the taxpayer may have can be offset against the taxpayer’s liability arising from the new or increased assessment.

Sections 139B and 139BA have been amended to ensure taxpayers are given the same amount of time as they previously were given for payment of the tax before the imposition of late payment penalties. Section 142B has also been amended to ensure taxpayers have the same amount of time for payment of any shortfall penalties.

Application date

The amendments came into force on 5 February 2017

Prescribed forms

An amendment to section 35 of the Tax Administration Act 1994 has been made to confirm that information required under a prescribed form can be provided verbally (including by telephone or in person) when the Commissioner of Inland Revenue considers that to be appropriate.

Background

Section 35 allows the Commissioner to prescribe forms and electronic formats that have not otherwise been prescribed. This could be interpreted as requiring the information required under the prescribed form to be provided electronically or in writing, excluding providing the information verbally.

With some prescribed forms it is easier for taxpayers and more efficient for Inland Revenue if the information (or some of the information) required in the form can be provided verbally. For example, more than 50 percent of the paper GST registration forms submitted are incorrectly completed. If the taxpayer was not able to verbally correct their registration form, they would have to complete the registration form again and send it in a second time. This change confirms that an Inland Revenue staff member can telephone the taxpayer and correct the errors on the basis of their discussion with them.

Key features

Section 35 has been amended to give the Commissioner a discretion to allow a person to provide the information in a prescribed form in a manner other than writing if the Commissioner is satisfied that, in the circumstances, it is appropriate.

This discretion will not be exercised in all circumstances – for example, it is not intended that information under a notice of proposed adjustment could be provided verbally.

Application date

The amendments came into force on 5 February 2017.

Administration of the late payment penalty rules

An amendment has been made to section 139B of the Tax Administration Act to enable Inland Revenue to continue to administer the late payment penalty grace period during the period in which tax types are operated out of two Inland Revenue software systems – FIRST (the older system) and START (the new system). An amendment to section 138E has been made to ensure certain rights of challenge do not apply to section 139B.

Background

A late payment penalty is imposed if a taxpayer does not pay on time. If a taxpayer has paid on time all relevant taxes due in the two years before the default in question, the Commissioner must issue a notice to the taxpayer specifying a further date for payment of the unpaid tax (a “grace period”), before late payment penalties can be imposed.

Tax types will transition from Inland Revenue’s older FIRST system to the START system in stages. This raises an issue in relation to the grace period, as information relating to the taxpayer’s compliance history will reside in two systems.

Key features

Section 139B has been amended to introduce a discretion into the provisions setting out whether a taxpayer is entitled to a grace period from late payment penalties. The discretion will enable the Commissioner to ignore defaults in payment if:

- doing so is necessary due to tax types being administered from different systems as a result of the coexistence of FIRST and START; and

- doing so would not result in the imposition of a penalty that is greater than would otherwise have been imposed (had she not ignored these defaults in payment).

In practice, this discretion will be applied to allow the Commissioner to look only at the tax information about a taxpayer’s compliance history held in the system from which the tax type in default is being administered. For example, if the taxpayer defaults on a GST payment and GST is being administered in START, the Commissioner would only look at the taxpayer’s compliance history in START to determine the taxpayer’s eligibility for a grace period.