4 - Inland Revenue’s regulatory systems

- Revenue raising and collection

- Working for Families tax credits

- Child support

- KiwiSaver

- Student loans

- Paid parental leave

- Information sharing

This section sets out Inland Revenue’s regulatory systems and the “fit-for-purpose” assessments for each of these. These assessments were completed by Inland Revenue. Other agencies have been given an opportunity to comment where relevant and appropriate. We anticipate including further multi-agency input and stakeholder views to our updated fitness-for-purpose assessments in the next strategy.

There are seven systems:

- Revenue raising and collection, with two sub-systems – income tax and consumption tax;

- Working for Families tax credits;

- Child support;

- KiwiSaver;

- Student loans;

- Paid parental leave; and

- Information sharing.

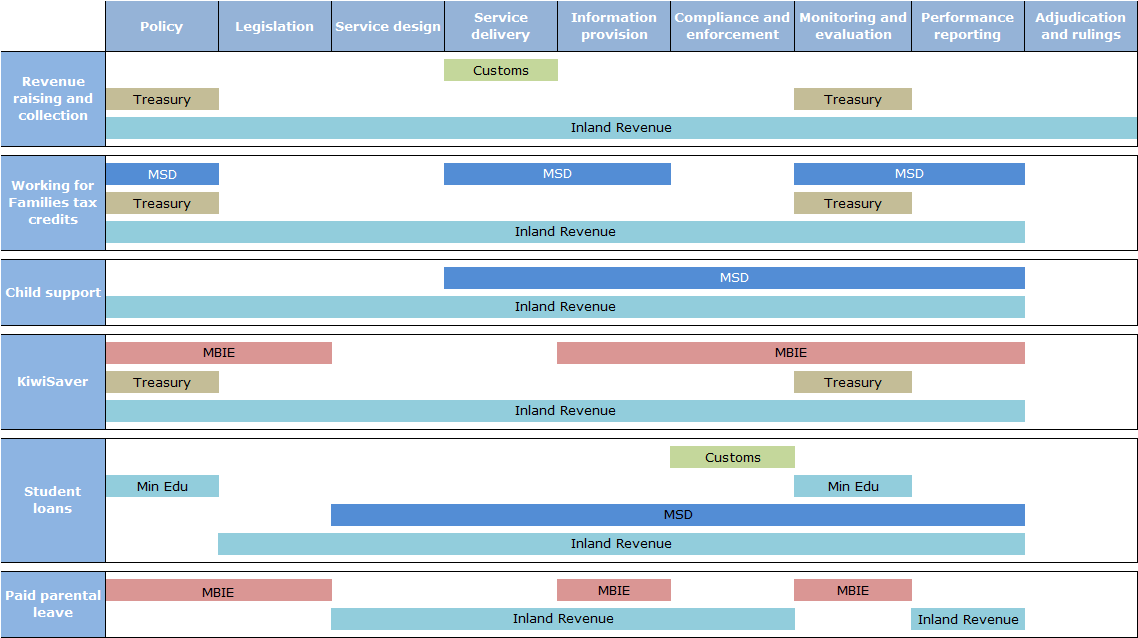

In some of our regulatory systems, some regulatory functions are carried out by other agencies.

The fit-for-purpose assessments cover four dimensions:

- Effectiveness – To what extent does the system deliver the intended outcomes and impacts?

- Efficiency – To what extent does the system minimise unintended consequences and undue costs and burdens?

- Durability and resilience – How well does the system cope with variation, change and pressures?

- Fairness and accountability – How well does the system respect rights and deliver good process?

The fit-for-purpose assessments of the regulatory systems were completed by Inland Revenue subject matter experts. Where possible, these assessments have drawn on research, international comparisons and information held by Inland Revenue. As appropriate these assessments were tested with other participants in those regulatory systems. Over time, as the Business Transformation progresses and information and analysis processes (including information sharing) are developed, Inland Revenue will refine its regulatory system assessments.

See Section Six for the current projects on the tax policy work programme and the regulatory systems they relate to.

Diagram 1: Inland Revenue regulatory systems – system and function view

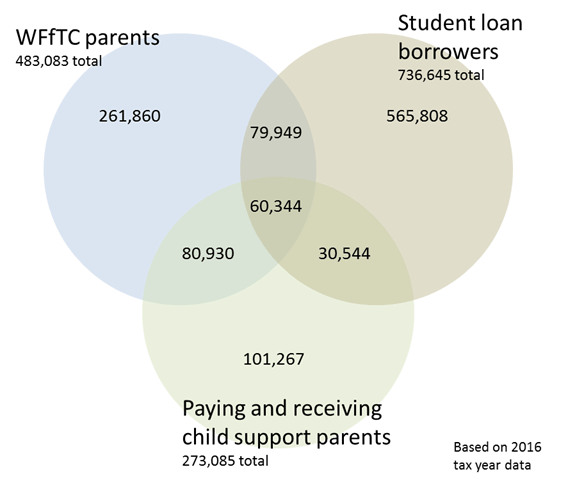

Diagram 2: Customers of Working for Families tax credits, student loans, and child support

Revenue raising and collection

System description

Inland Revenue designs and collects taxes on income from employment, investment and business conducted in New Zealand and from the consumption of goods and services in New Zealand. This revenue of around $60 billion per annum funds approximately 80 percent of government activity each year.

The income tax system also has a distribution and fairness element and in this there is a degree of overlap with the Working for Families system.

All New Zealanders directly or indirectly interact with the tax system throughout their lives. For most, this is a minimal interaction through the deduction of Pay As You Earn (PAYE) withholding tax from salary or wages, resident withholding tax (RWT) from interest, or as GST is collected by a vendor at the point of sale of a good or service.

More complex interactions with the tax system are experienced by businesses that may be subject to fringe benefit tax or company tax.

Taxpayers who have more complex interactions with the tax system are represented by sophisticated stakeholder advocates, including:

- Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand;

- New Zealand Law Society;

- Corporate Taxpayers Group;

- New Zealand Bankers Association; and

- Financial Services Council.

The tax system comprises a series of specific taxes, each of which is authorised by legislation. Though these can be analysed separately (and the two core elements are described below as sub-systems), it is important to recognise that a goal is for the tax system as a whole to operate coherently.

The fit-for-purpose assessment for the revenue raising and collection system covers:

- the overall tax system;

- the income tax sub-system; and

- the consumption tax sub-system.

The overall tax system

Key legislation

Income Tax Act 2007

Tax Administration Act 1994

Goods and Services Tax Act 1985

Gaming Duties Act 1971

Stamp and Cheque Duties Act 1971

System agencies

Inland Revenue (Policy and Delivery)

Treasury (Policy)

New Zealand Customs Service (Deliver – some GST collection)

Department of Internal Affairs

Effectiveness

New Zealand’s tax system provides reliable sources of revenue to fund Government programmes. New Zealand’s tax revenue amounts to around 30 percent of GDP.

A key element in a good tax system is having a coherent framework. This ensures all the different parts of the system operate in support of each other. New Zealand’s broad-base low-rate (BBLR) tax framework provides a coherent approach.

The coherent policy framework is supported by good administration. New Zealand is ranked within the top 10 OECD countries for ease of paying taxes.

Efficiency

New Zealand collects about 90 percent of its tax revenue from the three core taxes (personal, company and GST). New Zealand does not have taxes on transactions or turnover, such as stamp duty and cheque duty, which international tax reviews have identified as being particularly inefficient.

As noted, New Zealand’s tax system is based on a broad-base, low-rate framework. The advantage of broad bases is they ensure taxes are able to raise the required amount of revenue without resorting to high rates of taxation. This minimises the extent by which taxes distort economic activity and do as little as possible to impede economic growth. Low rates minimise deadweight losses and also minimise incentives for non-compliance.

Despite not having the economies of scale of most other developed economies, the New Zealand tax system operates efficiently in terms of administrative costs per dollar of revenue collected. International comparisons also suggest New Zealand imposes low compliance costs on taxpayers. The 2016 survey of tax compliance for SMEs indicated the costs of compliance had fallen by approximately 25 percent since the previous survey in 2013.

Tax policy is developed in accordance with the Generic Tax Policy Process (GTPP). The GTPP is an open and interactive process whereby private sector representatives, particularly tax practitioners, are able to provide input into policies and policy design to remedy problems and improve implementation.

Durability and resilience

The BBLR framework is very durable. It was introduced in the mid-1980s replacing a highly distortionary system with patchy application and some very high rates. Since then there has been buy-in from the public and successive tax reviews have supported the BBLR framework.

Leading tax practitioners with experience in New Zealand and overseas have commented on the very different nature of tax debates in New Zealand and other countries because of a lack of clear policy frameworks in other countries. A clear framework promotes compliance because it helps courts to decide what is and what is not avoidance.

International surveys have indicated New Zealand’s tax system is perceived as more consistent and predictable than most other countries.

Though the overall framework has been stable, tax policy has evolved to reflect Government priorities, new interpretations of the law, innovations in business practice, tax policy developments in other countries and concerns of key stakeholders. Inland Revenue publishes and periodically updates its tax policy work programme which sets out the issues which will be worked on over the coming 1–2 years.

The tax policy work programme (see Section Six) reflects the fact that to be resilient the tax system needs ongoing maintenance and enhancement.

Fairness and accountability

The GTPP provides the private sector with opportunity to influence tax policy. This has contributed to open and constructive policy debates, which is a hallmark of the New Zealand tax system.

The disputes resolution process is designed to ensure that there is a full and frank communication between the parties in a structured way within strict time limits for the legislated phases of the process.

The disputes resolution process is designed to encourage an “all cards on the table” approach and the resolution of issues without the need for litigation. It aims to ensure that all the relevant evidence, facts and legal arguments are canvassed before a case proceeds to a court.

The income tax sub-system

System description

The income tax system has two objectives: to raise revenue and to redistribute income through the use of a progressive tax scale.

Individual income tax is the largest component of New Zealand’s tax system. It collects approximately 40 percent of New Zealand’s tax revenues.

Most of the personal income tax is collected through employers deducting employees’ tax through the PAYE system. For many workers, the amount of tax deducted is accurate and they have no need to file a tax return at year end. Self-employed workers pay their tax either by having tax deducted through schedular arrangements or by paying provisional tax throughout their income year.

Company income tax raises around 15 percent of total tax revenue. The company income tax system is designed to be a backstop for taxing the personal income of domestic investors. Company income tax is 28%, but New Zealand-based investors can claim imputation credits for tax paid by the company when the income is taxed upon distribution at the personal level.

At the same time, the company tax is designed as a final tax on the New Zealand-sourced income of foreign investors.

Individual income tax

Effectiveness

The recently published OECD Report Taxing Wages 2015–16 pointed to New Zealand’s personal tax system being effective at raising revenue while maintaining relatively low tax rates and therefore minimising distortions.

The personal tax collection as a percentage of GDP in New Zealand is 12.6 percent – the 5th highest in the OECD. At the same time, New Zealand has low tax wedges – that is, low average tax rates.

The tax wedge varies according to family composition and interaction with the progressive tax scale. Across a range of family types and income levels examined by the OECD, New Zealand has low tax wedges compared with OECD countries.

For instance, for single workers on the average wage with no dependents, the tax wedge in New Zealand is 17.9 percent. This is the second lowest in the OECD. The OECD average is 36 percent.

For a family with one earner on the average wage and two dependent children, the tax wedge in New Zealand falls to 6.2 percent because of Working for Families tax credits. This is the lowest rate in the OECD. The OECD average is 26.6 percent.

This outcome – low wedges but high levels of revenue – reflects the absence of allowances or dispensations and relatively good compliance by taxpayers.

Individual income tax, in combination with the transfer system, redistributes income. By one measure of redistribution or progressivity, namely the extent by which the average tax wedge grows as income grows, New Zealand is slightly more progressive than the OECD average.

An alternative approach is the extent to which the tax and transfer system reduces inequality. OECD data indicates that New Zealand reduces a standard measure of inequality, the Gini coefficient, by slightly less than the OECD average.

Efficiency

The extent by which taxes produce deadweight losses is influenced by average and marginal tax rates. In terms of average tax rates, as described above, the New Zealand system performs well. This is also the case for marginal tax rates; New Zealand’s highest marginal tax rate of 33% is relatively low by international standards.

However, because of the interaction with the transfer system, some low-middle income taxpayers face higher effective marginal tax rates because of the combined impact of benefit abatement and personal taxation.

The PAYE system provides an efficient means of collecting tax because compliance sits with the (relatively) few employers rather than the more numerous employees. The provisional tax system for self-employed is more onerous; Inland Revenue’s Business Transformation is creating opportunities for these processes to become easier for taxpayers by taking into account business cash flow and leveraging off accounting systems.

New Zealand’s broad income tax base allows a lower rate, which increases efficiency. Expanding the base further, to include (for example) capital gains could allow a further reduction in income tax rates over time, but efficiency gains from lower rates have to be balanced against efficiency costs of realisation-based capital gains taxes themselves (for example, the lock-in of assets due to a desire to defer realisation through sale) and the high administrative cost of a capital gains system.

Durability and resilience

New Zealand’s personal tax system and collection through the PAYE system is long-standing. The system is amenable to periodic adjustments, such as the changes to tax thresholds introduced in the 2017 Budget.

Fairness and accountability

Generally, taxpayers with similar levels of income will pay similar amounts of tax, irrespective of the source of that income. One partial exception is that income earned as a capital gain is generally not taxed. Successive reviews of the New Zealand tax system have noted this gap but also noted the significant complications of a capital gains tax and consequently not recommended one be adopted.

For most individuals, tax is deducted through the PAYE system. For those with stable incomes throughout the year, this produces an accurate deduction of tax and many such taxpayers do not need to file an annual return. For taxpayers with variable income, or those who are self-employed and pay tax through the provisional tax system, tax deductions are not as certain or reliable. However, all such taxpayers are required to square up their tax after the year-end, so taxpayers with identical total income will face identical tax obligations however the income is earned. This approach does create compliance for employers however this is the most efficient approach overall for the economy as the total cost of compliance would be significantly higher and accuracy would be significantly lower if all individuals completed their own income tax calculations.

Company tax

Effectiveness

To support the domestic personal tax system, the company rate should ideally be aligned to the top personal tax rate. In New Zealand this is almost but not fully achieved; the company rate being five percentage points below the top marginal tax rate.

New Zealand, however, also has to consider how its company tax rate compares with that of other countries. This is because multinational companies will have incentives to allocate their expenses to countries with higher tax rates and their profits to countries with lower tax rates. Around the world, there is a downwards trend in company rates and New Zealand now sits above the OECD average, thereby creating pressure for New Zealand’s rate to reduce. However, in addition to the revenue implications, a lower company tax rate would widen the gap with the top marginal rate for personal income.

Efficiency

New Zealand’s dividend imputation system prevents company income from being double taxed (for New Zealand investors). In addition the (reasonably) close alignment of the company tax rate with the highest personal rate means that there is little incentive for incorporation decisions to be driven by tax considerations. In other words, the tax system is not driving economic choices, an outcome which is likely to be efficiency-enhancing.

As a final tax on New Zealand-sourced income of foreign investors, the efficiency of the tax is related to the level of location-specific “economic rents” (that is, above-normal returns) earned by those investors. If foreign investors are earning above-normal returns, taxing them is an efficient source of revenue because the tax does not discourage investment. If they are not earning above-normal returns then the tax will lower investment in New Zealand, which will ultimately be borne by New Zealanders in the form of lower wages or higher consumer prices. Inland Revenue’s view is that there are location-specific rents being earned by foreign investors and so taxing them is a relatively efficient way of raising revenue.

Durability and resilience

New Zealand is a participant in the OECD’s base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) initiatives. These initiatives aim to ensure multinationals pay tax in the countries where their economic (as opposed to accounting) profits are earned.

Fairness and accountability

Taxing income at the company level increases fairness because it means that individuals are less able to defer taxation by holding assets or earning income in a company. For policy reasons there are a number of income tax exemptions (for example, registered charities).

See also the comments in the assessment for the revenue raising and collection system.

The consumption tax sub-system

System description

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) is a tax on goods and services consumed in New Zealand, which is borne by the final consumer. It is levied at the rate of 15%. It is primarily administered by Inland Revenue. However, the New Zealand Customs Service administers GST levied on goods imported into New Zealand.

Effectiveness

GST raises about 30 percent of New Zealand’s tax revenue. The tax is a very effective revenue raising instrument. The rate of 15% is amongst the lowest in the OECD yet the amount of revenue raised, as a proportion of GDP, is amongst the highest for that same group of countries.

This is a good example of how the BBLR framework applies in practice. New Zealand applies GST comprehensively, with very few exemptions or concessions. The main gap in this regulatory system is the importation of low value goods, which are currently exempt from GST. This is currently being considered in conjunction with Customs.

The GST has an economic effect of taxing all labour income at 15%, making it a flat rather than progressive tax. This is an example where fairness needs to be considered in the context of the entire tax system rather than individual taxes, as the progressive elements of New Zealand’s tax system are introduced through the personal tax and transfer system.

Efficiency

The GST compliance gap is an estimate of the shortfall in GST collection compared with what one could expect based on the Department of Statistics measurement of consumption expenditure. New Zealand’s compliance gap appears to be in the 2–4 percent range, which is lower than that estimated in other comparable countries.

Durability and resilience

GST is durable as it has been in place for 30 years. In that time, the rate has been increased twice.

It is a well-regarded scheme because its comprehensiveness and simplicity assist compliance and administration.

Fairness and accountability

See comment in the revenue raising and collection assessment.

Working for Families tax credits

System description

Working for Families is a package designed to help make it easier to work and raise a family. It pays extra money to many thousands of New Zealand families. Greater financial support is available for:

- almost all families with children, earning under $70,000 a year;

- many families with children, earning up to $100,000 a year; and

- some larger families earning more.

There are four types of tax credits:

- family tax credit;

- in-work tax credit;

- minimum family tax credit; and

- parental tax credit.

Inland Revenue administers the programme jointly with the Ministry of Social Development. In the 2015–16 financial year, we distributed $2.4 billion in entitlements to support families.

Key legislation

Income Tax Act 2007

System agencies

Inland Revenue (Policy and Delivery)

Treasury (Policy)

Ministry of Social Development (Policy and Delivery)

Effectiveness

The Working for Families tax credit system (WfF) is generally effective in providing low to middle income families with regular payments. Payments are easy to apply for and the majority of services are available online either through Inland Revenue or MSD.

Around 70 percent of New Zealand families with dependent children receive Working for Families tax credits either through Inland Revenue or MSD.

In order to receive regular payments families must estimate their anticipated earnings for the coming tax year – this can be difficult and an incorrect estimate can lead to either over or under payment of entitlements. Families can avoid this risk by opting to receive their payments at the end of the year, however this undermines the intent of WfF which is to provide support when it is needed.

Changes proposed as part of the social policy Business Transformation project aim to remove this uncertainty by replacing the income estimate and instead calculating WfF entitlements based on recent, actual income.

The amount of child support a person pays or receives will increase or lower (respectively) their income for Working for Families which may then lower or increase (respectively) their WfF entitlements.

Efficiency

The shared delivery model with MSD has advantages in that it allows beneficiaries to deal only with MSD with regards to their entitlements, but also disadvantages in that it necessitates information shares between the departments as well as complexity for families coming off or going on benefit.

The current WfF system generates a high level of low value contacts from families trying to estimate their income and dealing with the consequences of incorrect estimates.

In 2015–16, 99.3 percent of WfF tax credit payments were made on the first regular payment date following an application.

Durability and resilience

WfF rates and eligibility rules are contained within the Income Tax Act 2007. The ability the system has to respond to changes in the environment is limited by the legislative process. To date this has not proved to be an impediment as generally information technology system changes require a longer lead in than the normal bill processes allows.

Both Inland Revenue's and MSD's transformation programmes aim to provide a more responsive operating systems that can be quickly updated which will allow Government to react faster to environmental changes.

Fairness and accountability

Having the WfF rules in legislation provides a high level of transparency as all of the criteria and entitlement rates are publicly available. However, one consequence of having the rules in legislation is that they do not always cater to unusual or exceptional circumstances, which can mean in rare cases the law, as written, does not achieve the desired policy outcome.

Changes proposed as part of the social policy Business Transformation project aim to introduce some flexibility by allowing the Commissioner limited discretion in how to apply the law when dealing with unusual or exceptional circumstances.

The Generic Tax Policy Process ensures that any changes to the rules are subject, where possible, to robust public consultation prior to the introduction of any legislative amendment.

Child support

System description

The child support scheme makes sure that:

- parents take financial responsibility for their children; and

- financial contributions from liable parents help to offset the cost of benefits that support their children.

Inland Revenue collects child support payments. In the 2015–16 financial year, we collected $474 million from 170,000 liable parents who pay child support and distributed $280 million to carers. The balance goes to the Crown to offset sole parent benefits paid to custodial parents by the Ministry of Social Development.

Key legislation

Child Support Act 1991

System agencies

Inland Revenue (Policy and Delivery)

Ministry of Social Development (Policy and Delivery)

Effectiveness

Child Support is a compulsory regime for beneficiaries and an optional regime for parents who are unable or do not want to come to a private arrangement.

Child Support is assessed using annual income information from the previous calendar year or two tax years ago. This means that parents and carers know what payments they will have to make or what they might receive.

However, there are some issues. Payments based on old income information may not reflect the current ability of each parent to contribute to the cost of raising a child.

Changes proposed as part of the social policy Business Transformation project aim to make child support assessments better reflect the ability of the liable parent to pay and the receiving carer's need for support at the time by basing assessments on more recent income information.

The child support formula considers each parent’s income and the amount of care they have for each of their children. While the regime works well for most situations, the definition of income is based off concepts from tax legislation. This can mean that some people are able to artificially reduce their income for child support by taking advantage of structures like trusts and companies or transactions such as loans and fringe benefits.

Changes proposed as part of the social policy Business Transformation project would broaden the definition of income used so that it encompasses a wider range of incomes that, while they may not be taxable, are available to the parent and should be taken into account in assessing their ability to contribute to the costs of the child.

The amount of child support a person pays or receives will increase or lower (respectively) their income for Working for Families which may then lower or increase (respectively) their WfF entitlements.

Efficiency

The current system uses the PAYE deduction regime for income tax to deduct child support obligations from liable parents who either elect to have them or who have fallen into arrears. Once a payment is made by the liable parent, it can take a while to get to the receiving parent or carer.

It is proposed that liable parents who receive salary, wages or contracting income subject to withholding tax would be required to have child support deductions. This would help those parents meet their obligations automatically and reduce the number of liable parents falling into debt. Once payments are received they will be able to be immediately passed on to the receiving carer.

The system is most efficient when the liable parent is New Zealand based as it can leverage off the information received through the PAYE system and other elements of the tax system. Once a liable parent leaves New Zealand there are a number of arrangements and agreements between countries to support the collection of child support obligations.

In 2015–16, 80.2 percent of child support assessments were issued within two weeks (the target is 80 percent).

Durability and resilience

The child support regime is contained within the Child Support Act 1991. The ability the system has to respond to changes in the environment is limited by the legislative process. To date this has not proved to be an impediment as generally information technology system changes require a longer lead in that the normal bill processes allows.

Inland Revenue's transformation programme aims to provide a more responsive system that can be quickly updated which will allow Government to react faster to environmental changes.

Fairness and accountability

All the criteria and entitlement rates for child support are set out in legislation. This provides a high degree of transparency. However, one consequence of having the rules in legislation is that they do not always cater to unusual or exceptional circumstances, which can mean in rare cases the law, as written, does not achieve the desired policy outcome.

Changes proposed as part of the social policy Business Transformation project aim to introduce some flexibility by allowing the Commissioner limited discretion in how to apply the law when dealing with unusual or exceptional circumstances.

The Generic Tax Policy Process ensures that any changes to the rules are subject, where possible, to robust public consultation before the introduction of any legislative amendment.

There are also a number of different kinds of independent reviews available to parents who believe that their specific circumstances have not been taken into account. These reviews are based on Family Court processes and are contracted to independent review officers.

Following the recent reform of the child support regime, which made changes to improve the fairness of assessments by looking at the incomes of both parents, Inland Revenue has undertaken research to measure whether these reforms have changed people's perspectives of the regime. Taken as a whole there was a slight increase in customers’ perceptions that the child support system is fair.

KiwiSaver

System description

KiwiSaver helps individuals save for retirement. Under the scheme, savings are accumulated through a combination of employee and employer contributions, and the member tax credit (an annual contribution by the Government to eligible members, aimed at incentivising saving). Inland Revenue and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) are jointly responsible for administering the KiwiSaver Act 2006. Inland Revenue collects contributions and transfers them to scheme providers for investment. In the 2015–16 financial year we transferred approximately $5 billion to scheme providers. As at 30 June 2016 there were approximately 2.64 million people enrolled in KiwiSaver.

This assessment does not account for the areas of KiwiSaver legislation MBIE is responsible for administering.

Key legislation

KiwiSaver Act 2006

System agencies

Inland Revenue (Policy and Delivery)

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (Policy and Delivery)

The Treasury (Policy)

KiwiSaver scheme providers

Effectiveness

KiwiSaver is an opt-out savings vehicle designed to make it easier for New Zealanders to save for their retirement. With over 2.64 million members KiwiSaver is now the primary way most New Zealanders save for their retirement.

However, while KiwiSaver membership is high the majority of members only contribute funds at the minimum rate of 3%t. (For the 2015–16 year approximately 66 percent of employees were making contributions at a rate of 3%.) In 2015 approximately 119,200 members were on a contribution holiday. There are also concerns about members who have been on contribution holidays for over five years (meaning no contributions have been made to their KiwiSaver fund during this time), and members who do not contribute enough to receive the full member tax credit entitlement.

Inland Revenue and MBIE are currently working on policy initiatives aiming to encourage members to increase their level of contributions, and therefore to increase the funds members will have accumulated to support themselves in retirement.

Efficiency

KiwiSaver acts as a low-cost managed retirement saving vehicle. As employee contributions are made concurrent with PAYE deductions, KiwiSaver is convenient and does not have compliance costs for members. KiwiSaver is currently broadly available to New Zealand residents up to the age of 65. And as part of the policy increasing the New Zealand Superannuation age, the Government has agreed to remove the upper age limit for KiwiSaver membership.

Inland Revenue aims to be efficient in its administration of KiwiSaver. Contributions for existing members are transferred to scheme providers in under a month, and it is anticipated this time will be further decreased as part of Inland Revenue’s Business Transformation programme.

Durability and resilience

KiwiSaver legislation is principally contained in the KiwiSaver Act 2006. Therefore, the initiative’s ability to react to environmental and economic changes is affected by the length of the legislative amendment process. However, to date this has not generally been an issue. Any significant changes to KiwiSaver policy settings generally require system changes that have a longer lead in time than the average bill process.

KiwiSaver scheme providers offer a choice of fund types, with varying degrees of risk and return. This, along with the ability for members to go on contribution holidays, adds a degree of flexibility to the scheme and considers the current financial situation and long-term savings needs of individual members.

Fairness and accountability

The KiwiSaver regime is set out in legislation. This provides a high degree of transparency. In addition, information about KiwiSaver (including statistical analysis, which is updated monthly) is publicly available on the Inland Revenue’s KiwiSaver website. Each of the nine default KiwiSaver providers also have websites where information can be publicly accessed.

Members can make complaints about Inland Revenue’s administration of KiwiSaver by following Inland Revenue’s complaints process, which is outlined on the Inland Revenue website. Scheme providers are subject to accountability mechanisms set out in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013.

Student loans

System description

Student loans make tertiary study more accessible to a wide range of people so that they may gain the knowledge and skills that enhance the economic and social well-being of New Zealanders. Inland Revenue jointly administers the student loan scheme with the Ministry of Social Development (StudyLink).

The Ministry of Education is the lead agency for student loans and is responsible for strategic policy advice, forecasting demand and costing the scheme. The Ministry of Education sets the policy parameters within the context of the New Zealand tertiary education system and the goals of the Tertiary Education Strategy.

StudyLink assesses loan eligibility and entitlement and makes student loan payments.

Inland Revenue maintains student loan accounts after the loan is transferred from the Ministry of Social Development. Inland Revenue collects student loan repayments and ensures repayment obligations are met by borrowers. There were 731,754 borrowers at 30 June 2016 and Inland Revenue collected $1.2 billion in repayments in the 2015–16 financial year.

This assessment is limited to Inland Revenue’s responsibility for administering the legislation, particularly repayments and compliance with obligations. The Ministry of Education, as the lead agency with overall responsibility for the student loan scheme, and the Ministry of Social Development have reviewed this assessment.

Key legislation

Student Loan Scheme Act 2011

System agencies

Inland Revenue (Delivery)

Ministry of Education (Policy)

Ministry of Social Development/StudyLink (Delivery)

Effectiveness

Since the student loan scheme began in 1992, students have borrowed $23,146 million and loan repayments of $11,480 million have been collected ($1,208.8 million in the 2015–16 year). Nearly 450,000 borrowers have repaid their loans since the scheme began.

Compliance with repayment obligations is high for New Zealand-based borrowers – only four percent were in default at 30 June 2016. However; 73 percent of overseas-based borrowers were in default at that time. Consequently, measures to improve compliance of overseas-based borrowers are a continuing focus.

Efficiency

The efficiency of the system in respect of collection of repayments from New Zealand-based borrowers arises through the low compliance costs imposed on borrowers who are wage and salary earners. Their repayments are assessed and collected by employers concurrently with PAYE.

Opportunities to improve collections from New Zealand-based borrowers who are not wage or salary earners have been identified and are in included in the discussion document Making tax simpler – Better administration of social policy, released in July 2017.

The efficiency of collections from overseas-based borrowers has shown significant improvement through a range of initiatives implemented progressively since 2010; the most recent being the match of student loan borrowers against the Australian Taxation Office database of taxpayers. Continued improvement is anticipated from new operational initiatives, such as a focus on establishing contact with borrowers who have left New Zealand, but are not yet treated as overseas-based borrowers, to ensure they are aware of their changed obligations and assist them to maintain repayments.

Durability and resilience

The system is subject to active oversight, through a scheme-wide approach to student loans, with lead Ministers and a virtual student loan agency.

The Minister for Tertiary Education, Skills and Employment is responsible for policy and the Minister of Revenue is responsible for the end-to-end operation of the student loan scheme, from lending to repayments.

The lead official of the cross-agency group takes an overall view of the scheme’s effectiveness and is accountable to Ministers for its overall effectiveness

Joint ministers meet quarterly. The three agencies with administrative responsibilities meet fortnightly to ensure early identification of emerging trends and development of appropriate responses.

Fairness and accountability

Borrowers can access information on each of the agency websites, which contain cross-links to relevant information. In addition, Inland Revenue continuously reviews the effectiveness of its direct marketing strategies to establish and maintain contact with overseas-based borrowers.

Rights of objection, to challenge and to disputes procedures are set out in law. Details of these rights are also set out on both the Inland Revenue and StudyLink websites.

Inland Revenue’s drive to improve the compliance of overseas-based borrowers will help to address a perceived lack of fairness when borrowers leave New Zealand for an extended period and choose not to continue loan repayments.

Paid parental leave

System description

Paid parental leave replaces a proportion of an employee's income from employment when they take parental leave. Paid parental leave payments are subject to PAYE deductions for income tax, student loan repayments and child support. Inland Revenue makes payments for the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. In the 2015–16 financial year, we made $217 million in payments to 26,300 parents.

The assessment below is limited to Inland Revenue’s agency role of responsibility for processing applications and making payments. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment were given an opportunity to contribute.

Key legislation

Parental Leave and Employment Protection Act 1987

System agencies

Inland Revenue (Delivery)

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (Policy)

Effectiveness

There were 2,222 new applications for paid parental leave (PPL) in May 2017 and 2,897 applications processed in the same period.

A high number of complaints (54) in the 2016 calendar year (and first five months of 2017) reflected a deficiency in the law which has been corrected with effect from 1 June 2017.

Statistics for May 2017 indicate awareness of the availability of PPL across all ethnicities and industry types.

In that month the majority of applicants had weekly income between $770–$960.

Efficiency

In 2015–16, 97.8 percent of PPL payments were issued to customers on the first regular pay day following the agreed date of entitlement (target was 97 percent).

The payments are made through a payroll-type system, which makes it possible to make child support, student loan and KiwiSaver deductions at the customer’s request.

Inland Revenue’s processes for handling annual adjustments to rates are set to be highly responsive. For instance it was possible to fully implement the new rates effective from 1 July 2017 after being notified of the rates on only 31 May 2017.

Durability and resilience

Paid parental leave is included in the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s employment relations and standards regulatory system.

Fairness and accountability

The primary source of information about eligibility for PPL is the MBIE website. However, the Inland Revenue website also contains basic information about eligibility, when and how to apply.

Information sharing

System description

The sharing of information between Inland Revenue and other agencies improves the effectiveness and efficiency of government. There are tensions between tax secrecy and cross-government information sharing. This tension has resulted in the Tax Administration Act having a number of legislated exceptions to tax secrecy to enable either the sharing of information from Inland Revenue to other agencies, or both the receiving of information from and sharing of information to other agencies to ensure the efficient and effective administration of the tax system.

Inland Revenue’s tax secrecy rule is set out in section 81 of the Tax Administration Act 1994 and requires all Inland Revenue officers to “maintain, and assist in maintaining, the secrecy of all matters relating to” the Inland Revenue Acts.

The confidentiality of tax information is important for three reasons:

- to balance Inland Revenue’s wide information-gathering powers;

- to promote voluntary compliance, whereby taxpayers are comfortable providing information to Inland Revenue if they know the information will not be disclosed further; and

- to maintain the integrity of the tax system, as tax secrecy is a critical component of the integrity of the tax system.

Key legislation

Tax Administration Act 1994

Sections 81 to 89 and 143C, 143D and 143E

System agencies

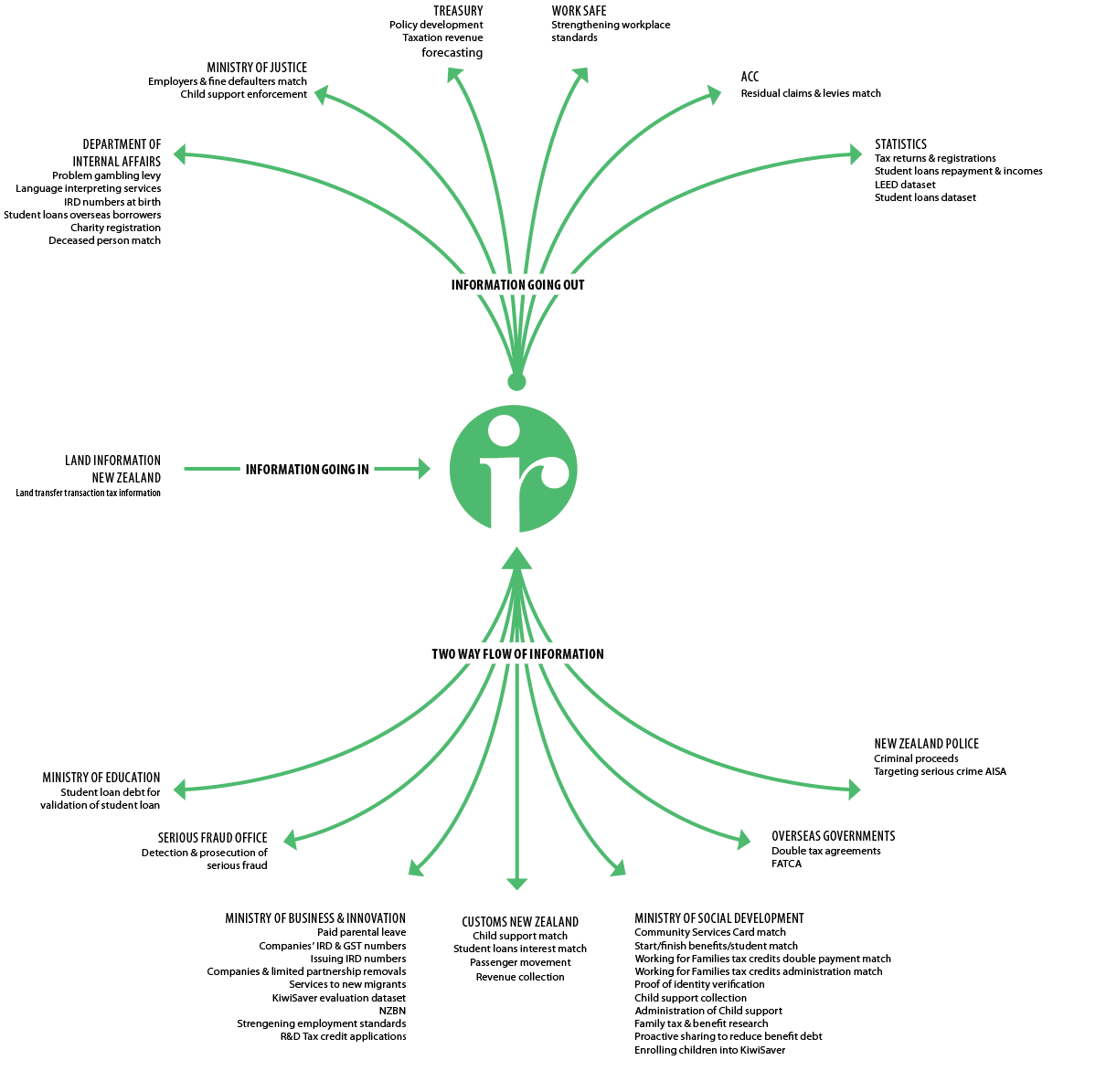

Multiple agencies – see diagram 3.

Recently Inland Revenue has also begun sharing information with:

- credit reporting agencies – sharing significant debt information on non-compliant taxpayers with Centrix Group Ltd, Dun & Bradstreet, and Equifax; and

- the Companies Office – sharing information on taxpayers who commit serious offences under the Companies Act 1993.

Effectiveness

The effective administration of the New Zealand tax system relies on taxpayers’ voluntary compliance. Critical to this compliance is taxpayers having trust in Inland Revenue that their information will not be disclosed inappropriately. However, to operate the tax system efficiently, or increasingly, for purposes relating to wider government, Inland Revenue sometimes needs to disclose information to taxpayers and third parties when it is reasonable to do so. An appropriate balance is needed in situations when these principles are inconsistent, and Inland Revenue strives to achieve that balance working in consultation with the affected parties and in collaboration with the agencies involved.

Efficiency

While the general rule regarding taxpayer information is one of secrecy, there are a number of targeted exceptions to this rule. In relation to these targeted exceptions, Inland Revenue currently has information-sharing agreements with several agencies.

These agreements are authorised either via specific exceptions contained in section 81(4) of the TAA, information matching provisions (sections 82–85 of the TAA and Schedule 3 of the Privacy Act) or broader information sharing provisions (section 81BA of the TAA or the new AISA regime).

The information sharing agreements aim at improving the efficiency and effectiveness of government by working with other agencies and private providers, as well as providing better services and outcomes to customers. The agreements are developed considering the risks and putting in place the appropriate safeguards to minimise unintended consequences, such as breaches of secrecy and privacy.

Durability and resilience

The tax secrecy rules in New Zealand tax legislation are long-standing. Similar rules about the confidentiality of taxpayer information are common across tax agencies internationally.

Inland Revenue already shares a significant amount of information with other agencies. However, the rules are constantly being looked at – seeking to be modernised and clarified to better provide for confidentiality and sharing in a customer centric and intelligence-led environment, and balance the trade-offs inherent in decisions about whether to share.

Fairness and accountability

Information is critical to Inland Revenue’s ability to perform its functions. Much of that information is provided by taxpayers. This may be information about themselves (such as in an individual or business income tax return) or about other taxpayers they deal with (such as in an employer monthly schedule). Inland Revenue can enforce the provision of information that is not received through regular channels and has significant powers to do so, but the use of these powers is the exception rather than the rule.

For taxpayers to be comfortable providing their information, they need to feel the information requested is reasonable and is treated appropriately by Inland Revenue. Currently, surety is given by what is often referred to as the tax secrecy rule – which essentially requires that information provided to Inland Revenue is for tax purposes and will only be used for such purposes.

Inland Revenue is working on refinements to the tax administration act in which the roles of the Commissioner, taxpayers and tax agents are articulated, as well as the rules around information collection and tax secrecy which underpin the interactions between these parties.

Diagram 3: Inland Revenue information sharing

Note: This diagram is simplified to reflect the main information flows between agencies and Inland Revenue. There are some instances, for example charities registration by Department of Internal Affairs, where information flows to Inland Revenue as well.