Chapter 7 - Making the system simpler

- Fringe benefit tax calculation for close companies

- Increasing the threshold for self-correction of minor errors

- Simplified calculation of deductions for dual use vehicles and premises

- Removing the requirement to renew resident withholding tax exemption certificates annually

- Increasing the threshold for annual FBT returns from $500,000 to $1 million of PAYE/ESCT

- Modifying the 63 day rule on employee remuneration

The Government has announced a number of proposals to simplify the tax rules for businesses to allow them to spend less time on tax compliance and more time on running their business.

The measures outlined in this chapter comprise:

- Fringe benefit tax (FBT) simplification for close companies;

- Increasing the threshold for self-correction of minor errors;

- Simplified calculation of deductions for dual use vehicles and premises;

- Removing the requirement to renew resident withholding tax exemption certificates annually;

- Increasing the threshold for annual FBT returns from $500,000 to $1 million of PAYE/ESCT; and

- Modifying the 63 day rule on employee remuneration.

Fringe benefit tax calculation for close companies

Close companies that provide their shareholder-employees with a motor vehicle for private use are required to register and pay FBT on that benefit, with some exemptions. On the other hand, sole-traders and partners of a partnership who use a motor vehicle as part of their business are not required to register and pay FBT on that motor vehicle. Rather, they apportion expenditure incurred in relation to that vehicle between business and private use.[36] The amounts relating to private use are not deductible for tax purposes.

This differing treatment for similar businesses arises purely because of the type of entity the business has chosen to trade through.

Close companies are required to calculate the availability of a vehicle for private use to work out the amount of FBT to pay. Often this is calculated on an annual basis as these taxpayers pay FBT annually. This creates an additional compliance burden when they are providing a single fringe benefit, when compared to similar businesses being run as a partnership or a sole trader.

The Government has announced that it will align the treatment of motor vehicles for these particular types of entities. This will remove the compliance costs incurred by a close company having to register for and pay FBT for no other reason than the provision of a motor vehicle to one or two shareholder-employees.

The rules for motor vehicle expenditure contained in subpart DE for sole traders and partnerships will be extended to apply to close companies. This will be optional as there may be some close companies that are comfortable with the current treatment.

There are three methods for apportioning business and private use:[37]

- Actual records - showing the reason and distance travelled for all business purposes;

- Logbook records – maintained for a test period of at least 90 days to establish the extent of business use. This can then provide the basis for determining the business use of the motor vehicle for a three year period; or

- Mileage rates – this method can only be used for less than 5,000 km of business travel - the actual business mileage is used multiplied by Inland Revenue mileage rates.[38]

Taxpayers who use this option will no longer have to file and pay FBT on the single benefit they provide to their shareholder-employees. Instead they can use one of these methods to claim motor vehicle expenditure.

For the avoidance of doubt, the private non-deductible portion of the expenditure will not be treated as a deemed dividend to the shareholder-employee.

It is proposed that the option would be available to close companies who qualify for the close company option in the FBT rules[39] on the basis that the only fringe benefit they provide is the availability of 1 or 2 motor vehicles for the private use of their shareholder-employees. These taxpayers will have a choice on how to account for the private use of a motor vehicle provided to a shareholder-employee.

One consideration for taxpayers is that in some circumstances there could be some GST adjustments required to reflect the change in how private use of the motor vehicle is calculated. These GST adjustments don’t currently arise for close companies under the FBT regime as GST is accounted for on the value of the benefit for FBT purposes.

In addition, further calculations will be required when the vehicle is disposed of to reflect the private element of any gain or loss made.

Example 23: Mary is the controlling shareholder of Percyville Books Ltd which has a 31 March balance date. She is the only employee of her company. The company provides Mary with a vehicle for both business and unlimited private use. During the 2017 income year Mary’s business use of the vehicle was 40% of the running. The total costs relating to the vehicle for the year were $3,250. The cost price of the vehicle was $20,000.

The company will have the choice of paying FBT on the availability for private use of the vehicle using the cost price of the vehicle as a basis and multiplying by 20% to get the value of the fringe benefit ($4,000) and pay FBT of $1,970.

Alternatively, Mary could use the actual business use of the vehicle to apportion the costs related to the vehicle using the actual use records from a logbook she maintains fastidiously. This would result in the business not claiming 60% of the total running costs of $3,250 (i.e. $1,950).

In addition, there will be differing adjustments required for GST purposes under each method.

Whilst in this example the option of measuring actual business use results in a deduction amount slightly less than the FBT amount to be paid, it does provide a more accurate measure of the business and private cost of the vehicle. It also aligns the treatment with other similar taxpayers who are not structured as a company.

There is a question as to whether making this proposal optional provides an opportunity for taxpayers to cherry pick methods to pay the least amount year-by-year. Officials propose restricting the ability for taxpayers to do this if the proposal remains optional. Officials are interested in submissions on how changing methods could be restricted and also whether this proposal should be compulsory for close companies that meet the criteria.

In addition, given the requirement to make adjustments for GST based on changes in actual use and when the motor vehicle is disposed of, officials consider the compliance cost savings of this proposal may be marginal. Officials would be interested in submitters’ views on this.

Increasing the threshold for self-correction of minor errors

Section 113A of the Tax Administration Act 1994 permits a person to correct an error in a return in the subsequent return where:

- The return contains one or more errors for income tax, FBT or GST; and

- The error was caused by a clear mistake, simple oversight or mistaken understanding by the person; and

- The total discrepancy is $500 or less.

If the error results in more than a $500 tax difference, then the taxpayer must ask the Commissioner to correct the error either through a voluntary disclosure or an application to amend the assessment under section 113 of the Tax Administration Act 1994. Interest and penalties may be payable on a shortfall corrected by the Commissioner.

The Government has announced that the self-correction threshold will increase from $500 to $1,000 of tax. This will allow taxpayers to correct simple errors of up to $1,000 (tax effect) in their next return.

The proposal will remove the compliance costs of having to apply to the Commissioner for relatively small amounts, and help ensure that interest and penalties do not discourage voluntary disclosure.

The $1,000 limit represents a maximum adjustment of income or deductions of $3,571 for a company, $3,030 for an individual and $7,667 for GST. These are relatively low values, particularly for larger businesses. Consequently, while the higher threshold will apply to all taxpayers, it will likely be of greatest benefit to small and medium businesses.

Example 24: Starliner Limited (Starliner) produces drawer liners with celebrity pictures. Ms Studebaker owns Starliner and does all the tax filing for the company. In March she realises that she omitted to include taxable supplies of $5,000 (incl. GST) on her February GST return, because she miscoded it to a liability account in her accounting system.

This resulted in shortfall of GST of $652.17. Previously Ms Studebaker would have had to file a voluntary disclosure or section 113 application to amend Starliner’s February GST return. Now she is able to self-correct this error in Starliner’s March GST return without the worry of interest or penalties, and it saves her time by not having to contact Inland Revenue.

It is possible that taxpayers are already self-correcting these errors without making an application to the Commissioner. While changing the threshold may not have much immediate impact, it will provide more certainty to taxpayers.

Consideration has been given to whether the self-correction threshold should be a percentage of the taxpayer’s tax or turnover rather than a flat amount. A percentage would result in a proportionate scale of self-correction (that is, the larger the business the larger the self-correction could be). However, this could allow large taxpayers to make significant corrections by dollar value, without review by Inland Revenue. For example, a taxpayer with a $50 million tax liability could make a $1 million adjustment if the threshold for self-correction was set at 2%. This represents $3.57 million of income or $7.67 million for GST. These are significant amounts, and for this reason a percentage threshold was not considered to be appropriate.

Simplified calculation of deductions for dual use vehicles and premises

Small business owners often use their personal vehicles and homes for both business and private purposes. Because there are numerous expenses for these items, allocating them between business and personal use can create a large compliance obligation compared to the amount of tax at stake.

In an effort to simplify the calculation of deductions and reduce compliance costs of calculating deductions for dual use home premises and vehicles, the Government has announced that taxpayers can use standard values rather than calculating actual costs. This proposal will generally only apply to small enterprises, as there is typically no private use of a larger enterprise’s assets.

Vehicles

It is proposed to extend and modify the current per kilometre option for calculating business use so it can be used regardless of kilometres travelled (the current rules only allow the method to be used if the business use is less than 5,000 km).

Under this proposal, taxpayers would deduct a fixed amount per kilometre travelled for business purposes based on rates published by Inland Revenue. This would be instead of deducting actual costs.

The rates would:

- Be set by reference to industry figures, and based on the average per kilometre cost for the average vehicle;

- Assume a fixed amount of private use in respect of the fixed cost element, so no apportionment between actual business and private use would be required;

- Be divided into two tiers. The first tier would provide for the recovery of both the vehicle’s fixed costs and per kilometre costs. The second tier would provide for the recovery of the per kilometre costs only (as the fixed costs of vehicle ownership would be over-deducted as usage increased if a single fixed rate was used); and

- Be published by Inland Revenue and updated each year to ensure they are accurate.

Taxpayers would keep a logbook for a three month representative test period to determine the vehicle’s proportion of business use for the next three years. Alternatively the taxpayer could elect to maintain a logbook for the entire year and record the actual distance travelled for business purposes.

The method would be optional to provide compliance cost savings for those who wish to use it. This is because there is a wide variance in the actual costs of car ownership, so a single rate would not be acceptably accurate for many taxpayers.

A more accurate compulsory method could be considered, but this would potentially erode the compliance cost savings.

A disadvantage of making the method optional is that some taxpayers will calculate their deductions under both options and claim whichever results in the greater amount. However, an optional method will still provide compliance cost savings for those who wish to use it. A taxpayer would, however, be prevented from changing methods for a particular vehicle to reduce their ability to game the methods on the same vehicle.

Example 25: Impala Limited (Impala) sells highly detailed model cars to collectors. As part of its business the owner of Impala, Chev Rolet, uses his personal car to deliver the models to various model shops around the city and also to the post office to send the models both within New Zealand and to international markets.

At the end of each year Chev has traditionally tried to work out the total running costs of the vehicle, which means he has had to keep private receipts, for petrol, insurance, maintenance etc. In addition, he has had to keep a logbook to determine his business versus private running of the vehicle.

Chev is keen to reduce the time it takes him to calculate the deduction for his vehicle and so begins using the new reimbursement rates set by Inland Revenue. The rates that Inland Revenue has calculated[40] are 74 cents per km for the first 5,000km and 20 cents for every km thereafter. Chev has kept a logbook for the first three months of the year which results in a ratio of business to total kilometres of 47%. Over the entire year Chev has driven 20,000km of which 9,400km (20,000 x 47%) have therefore been business related.

Impala therefore claims $4,580 (5,000 x 74 cents + 4,400 x 20 cents) in its tax return for motor vehicle expenses which it, in turn, reimburses to Chev.

Home premises

It is proposed that the deduction for business use of home premises be calculated by multiplying the number of square metres used primarily for business purposes by a single rate. The rate would be:

- Set by an Inland Revenue determination, based on the average cost of items such as utilities per square metre, but excluding rental or rates and mortgage interest costs;

- Updated each year to ensure it is not eroded by inflation;

- Different depending on whether the taxpayer owned or rented their premises; and

- Reasonably accurate for most taxpayers, as there is less variance in the cost of utilities etc. per square metre than there is for vehicle costs.

Taxpayers would also be able to claim a deduction for their actual mortgage interest, rates or rental costs, based on the percentage of the premises used primarily for business purposes. Officials consider there is too much variability in these costs for them to be included in a single representative rate.

The method will be optional. While the method should produce a fairly accurate measure for most taxpayers, some taxpayers will be entitled to smaller deductions under the method than their actual costs. Such taxpayers may consequently regard a compulsory measure as a cap on their deductions rather than a simplification. Introducing a new option will prompt some taxpayers to undertake both sets of calculations, in order to determine which gives the best result, and thereby undermine the compliance savings. It is unlikely that taxpayers would do this every year as premises expenses would likely remain fairly stable and so a reassessment of the calculation options would not be necessary.

Officials recommend only allowing a deduction for rent, rates and mortgage interest under this method where there is a separately identifiable part of the house which is primarily used for business purposes. This is because a house is used primarily for domestic purposes, so some threshold of business use should be required before the house can be regarded as used for dual purposes. It is also more difficult to apportion expenses where no identifiable part of the house is used for business purposes. Currently this is not a strict requirement, although apportionment is usually made on this basis. Submitters’ views on this point are welcomed.

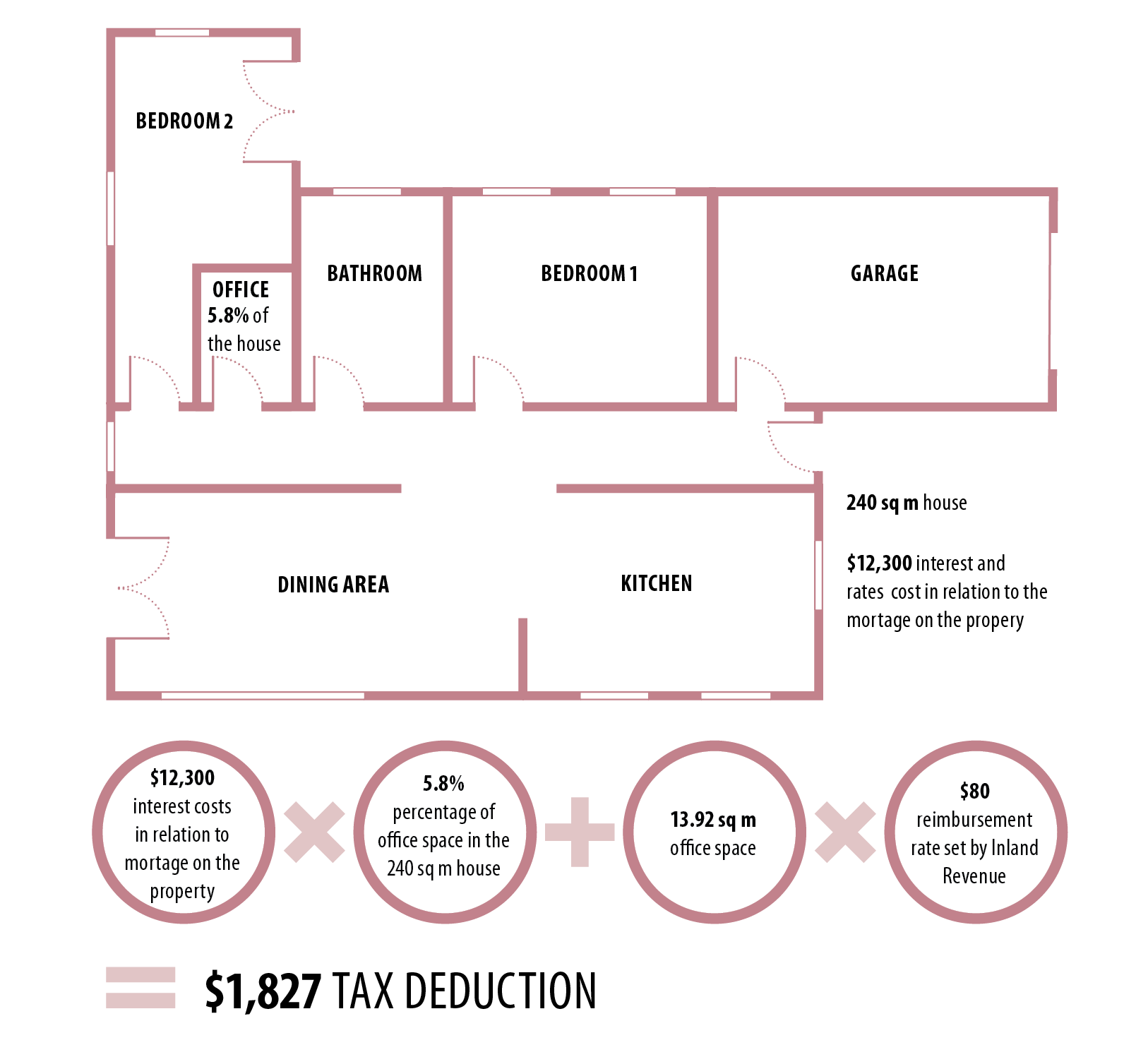

Example 26: Adventurer Limited (Adventurer) arranges adventure tourism activities in New Zealand for foreign tourists. George De Soto owns the company with his wife Flo and because of the timing of phone and video conference calls with foreign tour operators they have set up an office at home that is totally dedicated to the business.

Flo does all the tax compliance for Adventurer and finds it takes a significant amount of time to calculate the deduction that relates to the home office. She has to work out the costs of electricity and other utilities to get to a final figure to claim in Adventurer’s tax return. Flo is keen to use the Inland Revenue rates instead to save her the hassle of doing this each year.

She has worked out that the office space is 5.8% of the total floor area of 240 square metres of the house. She also knows that her interest and rates costs in relation to the mortgage on the property are $12,300. Inland Revenue has published the rate[41] that can be reimbursed in relation to a home office being $80 per square metre. Flo has calculated that the office takes up 13.92 square metres so takes a deduction in the tax return of Adventurer for $1,827 ($12,300 x 5.8% + 13.92 x $80). This calculation takes Flo a fraction of the time it used to take and works out to approximately the same amount.

Removing the requirement to renew resident withholding tax exemption certificates annually

Some taxpayers who hold a certificate of exemption from resident withholding tax (RWT) must renew their certificate annually. This is an Inland Revenue, rather than, a legislative requirement. Annual renewal is currently required if the applicant is applying for a RWT exemption certificate on the grounds that it has tax losses, a refund of over $500 RWT or estimated annual gross income of over $2 million. Applications on other grounds (such as actual annual gross income over $2 million in the prior year) do not require annual renewal.

Taxpayers have indicated that this is creating compliance costs for relatively little value to the overall system. The Government wishes to reduce these compliance and administrative costs by legislatively requiring RWT exemption certificates to be issued for an unlimited period. This would apply for all the available grounds of exemption, except for the taxpayer income estimation option. Inland Revenue would have the discretion to issue exemption certificates for a shorter period in exceptional circumstances.

Taxpayers will still be required to surrender their exemption certificates when they fail to meet the basis for eligibility on which it was granted. Inland Revenue will also retain its ability to cancel an exemption certificate.

There is a concern that as renewal is not required, Inland Revenue may be unaware that a taxpayer might no longer be eligible for a RWT certificate. Officials consider that this can be adequately mitigated by including a simple “tick the box” declaration on a taxpayer’s tax return. This would require the taxpayer to confirm that they are still eligible to hold their exemption certificate on the basis on which it was granted.

Example 27: Rambler Limited (Rambler) is owned by Bob Nash and arranges self-guided hiking trips. Rambler has not been doing well in the last few years due to people using phone apps to find their way on hikes rather than using the services of Rambler. Bob has created his own app that he hopes will turn the business around in the next five years. Until then Bob is keen for Rambler to obtain a certificate of exemption from RWT to get the funds back into Rambler. He applies for a certificate of exemption from RWT on the basis of the company being in tax losses. The Commissioner issues the exemption certificate to Rambler.

At the end of the year when filing its tax return Bob ticks the box which states that Rambler still meets the criteria to hold the certificate of exemption as it continues to be in a loss position.

Five years later, however, Rambler’s business has turned around and it is no longer in a tax loss position. At that point Bob returns the certificate of exemption to Inland Revenue as Rambler no longer meets the requirements to hold the certificate.

Increasing the threshold for annual FBT returns from $500,000 to $1 million of PAYE/ESCT

Most businesses are required to calculate and return FBT on a quarterly basis. However businesses with combined pay as you earn (PAYE) and employer superannuation contribution tax (ESCT) obligations of no more than $500,000 per year are currently allowed to calculate and return FBT on an annual basis.[42]

Where a smaller business becomes larger and employs more staff, it may exceed the $500,000 threshold and be required to calculate and pay FBT on a quarterly basis. This can impose compliance costs which are still significant relative to the size of the business and can act as a disincentive to employing extra staff.

The Government has announced an increase to this threshold which will allow a business with combined PAYE and ESCT of between $500,000 and $1m to continue accounting for FBT annually rather than changing to quarterly filing. This is intended to simplify compliance obligations for these businesses and lower their compliance costs.

It is estimated this change will benefit approximately 1,500 taxpayers who currently fall between the current and proposed thresholds and who file FBT returns.

Example 28: Eldorado Limited (Eldorado) is owned by Mr and Mrs Brougham and is a manufacturer of tacos. Because of the high quality of their tacos they are in demand and Eldorado needs more staff. They currently have 20 staff and have combined PAYE and ESCT obligations of $450,000 but need to double their employee count to 40. This will result in PAYE and ESCT obligations of $900,000.

Eldorado provides fringe benefits to staff including medical and life insurance and unlimited supplies of taco seconds. The Broughams undertake the tax compliance work for the business with the assistance of a local accounting firm Cady Limited. They are not looking forward to having to prepare FBT returns quarterly and the costs of having Cady Limited review and file the returns for them. They also do not want to stop providing fringe benefits to staff as they are well received.

Under the proposed change in the threshold for annual filing, Eldorado would not have to increase the frequency of filing until they tipped over the $1m threshold of combined PAYE and ESCT saving them both time and money they can instead devote to making tacos.

Modifying the 63 day rule on employee remuneration

Section EA 4 of the Income Tax Act 2007 contains rules regarding the deferral of deductions for employee remuneration. This rule is commonly referred to as the “63 day adjustment” or “63 day rule”. The 63 day adjustment overrides the ordinary “incurred” test for deductibility. The rule provides that a deduction for accrued employee remuneration can be claimed in the year it is incurred only if the remuneration is paid by the end of the 63rd day[43] after the end of that income year. Employee remuneration covers all types of payments of employment income including salaries and wages, retirement leave, holiday pay and bonuses.

The 63 day adjustment is intended to prevent taxpayers from claiming deductions for amounts of employee remuneration that have been accrued but not paid. It was introduced to specifically target deferred payment bonus schemes where employers were claiming large deductions for deferred bonus payments to staff and yet never paying those bonuses. This change is not intended to alter this fundamental principle.

Currently, in order to comply with this deferred payment rule, taxpayers need to work out what employee remuneration has been paid during the 63 day period that relates to items accrued at the end of the previous income year. This can create an additional compliance burden for taxpayers because they need to track payments accrued at year end and paid within 63 days of the end of the income year.

The current wording of the provision essentially imposes this compliance obligation on the taxpayer as they do not have a choice as to whether to take a deduction or defer this to the following income year.

The Government has announced it intends altering this rule to make the deduction for payments made within 63 days of the income year optional for taxpayers. For those taxpayers that do not wish to undertake the exercise, it would not be required and the deduction for those payments can be claimed in the following year.

Example 29: Skylark Limited (Skylark) is an airline that provides international passenger and freight services. It has a large workforce that comprises approximately 7,000 employees. At 30 June 2017, the end of Skylark’s income year, it has accrued employee remuneration of $58m, including accrued holiday pay of $12,000 for Bob Buick, representing 15 days annual leave.

At the end of the 63 day period (2 Sept 2017) the tax manager at Skylark asks the payroll team to calculate the 63 day rule adjustment for the company. The payroll clerks have to determine the amount of employee remuneration that was accrued at year end but paid out within the 63 days. Bob was lucky enough to be able to have a holiday to the United States to visit the extended Buick family.

He made the 13 hour flight worth it by taking 18 days annual leave from 5-31 August.

The payroll clerk has to match Bob’s 18 days of leave taken against his accrual at year end of 15 days and determine that for Bob, Skylark can only deduct $12,000 as the remaining 3 days leave was accrued after year end. The payroll clerk has to also do this for the 6,999 other employees.

At the end of the exercise, because the month of August is not a popular time for people to take leave from Skylark, Skylark claims $250,000 as a deduction for employee remuneration accrued at year end and paid within 63 days. This results in a reduction in Skylark’s residual income tax of $70,000, however it cost Skylark $30,000 to calculate.

Skylark decides that it will no longer undertake the 63 day rule calculation and instead will align the deductions with the payments made during the year to save the compliance costs of calculating the deduction.

For some taxpayers this will result in a simpler rule than the current 63 day rule deducting payments of employee remuneration incurred and paid up to the end of the income year. The proposed change will not affect those who wish to continue to undertake the work to determine the deduction based on the existing rule as the existing rule will be optional.

The current provision in section EA 4 will be modified to allow taxpayers to choose whether to apply the 63 day rule or not. Officials are interested in submitters’ views on the legislative aspects of this proposal.

36 In accordance with the rules in subpart DE of the Income Tax Act 2007.

37 See subpart DE 3 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

38 See page 72 for proposed changes to this method.

39 See subpart RD 60 of the Income Tax 2007.

40 These rates are used for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual or proposed rates.

41 Again this rate is for illustrative purposes only. It does not represent proposed or recommended rates.

42 Sections RD 60 and RD 61 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

43 This period is extended for shareholder-employee situations with extensions to file their tax returns.