Chapter 4 – Getting it right from the start

- Summary of proposals

- The assessment framework – right from the start

- Advice

- Returns and information collection

- Assessment

- Process for the Commissioner to amend an assessment

- Withholding taxes

- Payment of tax

- Disputes process

- Penalties

- Record keeping

Summary of proposals

- Moving to a situation where more of Inland Revenue’s resources are focused on helping taxpayers get it right from the start in part by prioritising advice to taxpayers. The aim is to provide the right level of certainty for a taxpayer at the best stage, subject to Inland Revenue’s resource constraints. Some of the specific proposals include:

- significantly reducing the fees for obtaining a binding ruling, at least for small and medium-sized enterprises;

- allowing post-assessment binding rulings;

- extending the scope of the rulings regime.

- Expanding the current approach to minor errors.

While there are numerous ways in which tax is, or could be, efficiently assessed, the Government has not yet moved away from the regular reconciliation process involving a periodic (such as annual) assessment. An assessment, which determines the final amount of tax payable, is a critical part of the tax collection function and underpins the role taxpayers and tax agents have in tax administration. The assessment is also the trigger point for a wide range of compliance and administrative actions by Inland Revenue.

The transformed tax administration will see significant changes to the assessment process, including better use of withholding payments, more pre-populated income tax returns and better use of a business’s existing systems to simplify interactions with Inland Revenue. This chapter, while outlining the direction of other areas, outlines proposals for two key aspects of the assessment process:

- the provision of advice by Inland Revenue

- the process by which taxpayers can amend their self-assessment.

The Business Transformation process does not suggest moving to a Commissioner-based assessment model in place of a self-assessment one. The legislative definition of an assessment recognises that assessments can be made either by the taxpayer or the Commissioner. Under the existing structure, if a taxpayer must file a return they must also make a self-assessment. No decision has been taken on whether this will change under Inland Revenue’s business transformation.

The assessment framework – right from the start

A key objective in modernising the tax administration system is to make tax compliance simpler. In the context of the assessment process this means helping taxpayers to “get it right from the start”. The “Right from the Start” approach is defined in terms of four dimensions that are considered central to the compliance environment:[45]

- Acting in real time and up-front, so that problems are prevented or addressed when they occur

- Focusing on end-to-end processes rather than only on the revenue body processes and trying to make taxpayers’ processes fit into them

- Making it easy to comply (and difficult not to comply)

- Actively involving and engaging taxpayers, their representatives and other stakeholders, in order to achieve a better understanding of taxpayers’ perspectives and to cooperate with third parties.

A “right from the start” approach supports compliant behaviour, drives out error and reduces the possibilities of non-compliant behaviour.[46] The purpose is not just to reduce unintentional mistakes, but also to reduce evasion and to strengthen the overall willingness to comply.[47]

The framework suggests the goal should be first time accuracy and a reduction in subsequent adjustments. This enhances taxpayer certainty and reduces the resources taxpayers and the Commissioner need to commit to the process. The different aspects of the tax assessment process, and the elements of tax administration that support the assessment process such as the provision of advice, need to be aligned with the overall framework.

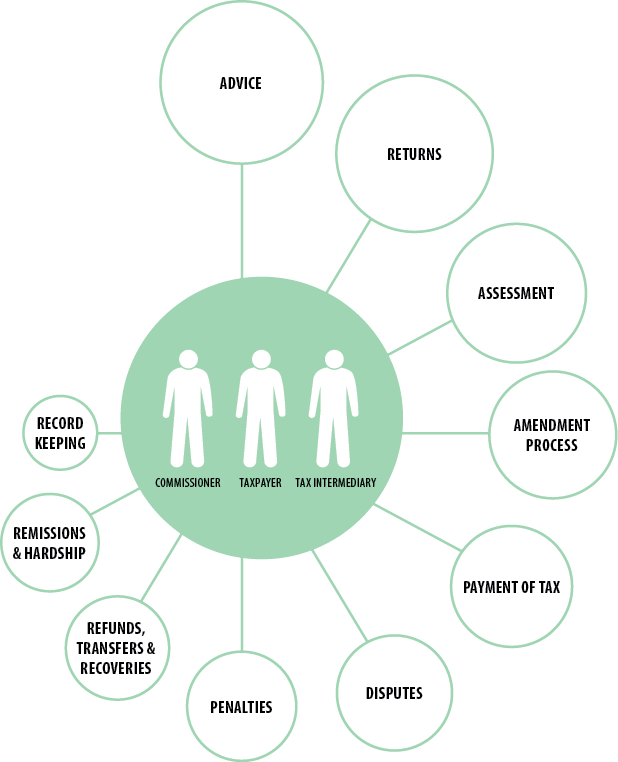

The right from the start framework involves many elements of the assessment process as indicated in the diagram on the next page.

While this chapter outlines proposals in relation to Inland Revenue advice and taxpayer amendments to assessments, the Government is aware that these two areas are only parts of the tax administration system and that the proposals in this chapter will need to work effectively with other aspects of the assessment process.

Advice

New Zealand’s system of assessment relies heavily on voluntary compliance, which requires taxpayers and their advisors to have a good understanding of the tax law to meet their obligations. Due to the complexity of the tax legislation, and the significant increase in the complexity of business and personal affairs, many taxpayers and agents will seek the advice of the Commissioner. A key reason for Inland Revenue to provide advice is that it will improve voluntary compliance as taxpayers will be more likely to understand and follow the tax rules.

The private sector (including tax intermediaries) will continue to play a significant role in providing advice to taxpayers. The Commissioner’s advice will continue to assist the private sector to in turn provide advice to their clients. The private sector will also help shape the advice offered by Inland Revenue.

Professional advisors offer a service to taxpayers which can be generally assumed to be a value for money proposition given the expertise required in providing the service. Professional advisors undeniably provide a valuable role in engendering greater taxpayer compliance. However, professional services can be expensive and, given Inland Revenue’s responsibility to manage the tax system, it is arguable that there is an onus on Inland Revenue to provide services that not only focus on compliance but also reduce compliance costs. This is consistent with the Commissioner’s obligation to protect the integrity of the tax system. The role of intermediaries is discussed in Chapter 5.

Advice and certainty

The current assessment system is focused on post-assessment amendments and audits. The Government proposes moving to a situation where more of Inland Revenue’s resources are focused on helping taxpayers to get it right from the start, reducing the need for post-assessment amendments.[48] One of the key aspects to support taxpayers will be the advice the Commissioner provides to them and their intermediaries. Clearer and better-timed advice should help taxpayers better ensure that their assessments are right first time.

The Commissioner currently provides a wide range of advice, from guidance over the phone to binding rulings. The range includes general advice and taxpayer-specific advice, and provides different levels of certainty for taxpayers.

One problem with the current range of advice provided by Inland Revenue is that it is focused on providing a set of advice products, such as booklets, public rulings, binding rulings and newsletters. It is not as focused on the specific needs of taxpayers as it could be and may be more weighted to some taxpayer groups than others. This means it may not align as effectively as it could with the taxpayer-focused model that is central to the Business Transformation process.

Ideally, the advice Inland Revenue provides should provide the right level of certainty for all taxpayers at the best stage, without being fixed on a particular advice product. At a minimum, this suggests that the current range of advice products needs to be more flexible and adaptive. It may involve extending the current range of products to more taxpayers. Over time it could evolve into more of a spectrum of advice, that is better focused on the specific needs of the taxpayer.

The key constraint in providing more individualised advice for taxpayers is that Inland Revenue will never have sufficient resources to advise all taxpayers about the implications of every transaction or income source. The Government expects Inland Revenue will need to balance its resources against the goal of providing more individualised advice and its other functions. The provision of advice will therefore need to be prioritised and streamlined for different contexts and to different audiences – for example, specific classes of taxpayers and for the wider public.

Inland Revenue is in the process of designing its future organisational structure, which will be crucial in determining how it will balance its resources and provide more effective advice. A view on the best way of providing advice to taxpayers is still to be finalised. However, some changes are suggested in this chapter to the binding rulings regime as part of the move to expand the type of advice that can be provided in the form of a binding ruling, to lower its cost and create more flexibility around the time at which a ruling can be sought.

General advice

The Commissioner currently provides a wide range of general advice to taxpayers, through public statements, guides, newsletters, booklets and the Inland Revenue website. General advice is relied on by a large number of taxpayers (especially small and medium-sized businesses), so it is very significant to the assessment process. The Government considers that general advice will continue to be the most important source of information for small and medium-sized businesses under the modernised tax administration. By increasing the volume and usefulness of general advice, the Commissioner may be able to some extent to reduce the need for individualised advice.

Binding public rulings provide a taxpayer with certainty if they come within the scope of the ruling (and no exceptions apply). A taxpayer cannot be subject to a reassessment, penalties or interest if a current ruling applies to them. Public Rulings will continue to play an important role in providing certainty to taxpayers. The Government is not proposing any significant change to the regime which is well supported by the taxpayers who use it. Inland Revenue will continue to seek improvements in the way small and medium-sized businesses can engage in the process for determining the public rulings work programme.

Other general advice provides a taxpayer who relies on it with a statutory defence against the imposition of shortfall penalties or interest (subject to some conditions).[49] As a result, taxpayers obtain some level of certainty from such general advice. While the taxpayer can still be reassessed for the amount of the core tax, the Commissioner has committed to only changing general advice on a prospective basis when the new view is unfavourable to taxpayers (unless exceptional circumstances apply).[50] This means the general advice usually provides certainty to taxpayers for past assessments of core tax.

Taxpayer-specific advice

The Commissioner currently provides a wide range of taxpayer-specific advice either over the phone or through other forms of correspondence. As with general advice, taxpayer-specific advice can provide greater but differing levels of certainty for taxpayers:

- Private binding rulings provide certainty to particular taxpayers on the core tax, penalties and interest. Although they are limited in number, they cover transactions worth more than $1 billion per annum.[51]

- More widely applicable, some taxpayer-specific advice is a Commissioner’s official opinion, which provides the taxpayer with certainty that interest or a penalty cannot be applied (subject to some conditions).[52] This assists with transparency and provides some certainty for taxpayers following the advice. It does not provide certainty for a taxpayer on the amount of core tax though. This is because the law does not allow the Commissioner to bind herself to a view on the law, other than through the binding rulings regime. This is consistent with the long-standing principle that the Commissioner cannot impose or suspend a tax without Parliament’s consent. However, when the Commissioner changes her view on taxpayer-specific advice (other than in a binding ruling), the new position will generally only apply on a prospective basis.

- Some taxpayer-specific advice does not meet the requirements to be an “official opinion”, such as if insufficient information has been provided to the Commissioner. This type of advice does not provide a statutory defence against interest and penalties, and may not provide sufficient certainty to a taxpayer for the amount of core tax.

Inland Revenue is investigating different channels for communicating to taxpayers. Traditionally, Inland Revenue has been reluctant to use electronic means of communicating with taxpayers due to concerns with maintaining confidentiality. As part of modernising the tax administration system, Inland Revenue is investigating more digital options. The increased use of technology should allow more customised advice to be provided to taxpayers. For example, one option being investigated is allowing Inland Revenue staff to see the same screen as the taxpayer in real time. This will allow the Inland Revenue staff member to more accurately guide the taxpayer.

Embedded advice

A significant new channel to aid taxpayers may in the future be through digital accounting products that interact with Inland Revenue’s new system. Inland Revenue is interested in exploring whether prompts and links could be embedded into accounting software. This would mean that tax information could be highlighted to software users through prompts created by the embedded rules. Inland Revenue is interested in further conversations with software providers on whether cloud-based accounting products may have the ability to provide prompts to taxpayers in the future through links to Inland Revenue publications or a suggestion to seek tax advice on a particular matter.

Example: Prompts and nudges in the United Kingdom

HMRC envisages the use of authorised computer software will allow a range of nudges and prompts to provide guidance to taxpayers. These could be pop-ups and questions within the software, which flag potential inconsistencies or errors to the taxpayer. In such instances, the software will ask the business to double check they are happy with the figures they are providing to HMRC.

For example, during the year Richard buys a new van for his business, but he is not aware that he is entitled to claim capital allowances against the purchase. When entering his van purchase into his accounting software, a pop-up message advises him of the capital allowances available, with a targeted link to online information. When he enters the cost of the van, the software automatically calculates the capital allowance and reflects it in his year-to-date tax figure.

Binding rulings regime

One of the key methods of providing certainty for taxpayers is the binding rulings regime. This has been reviewed from time to time, resulting in some minor legislative changes over the years. There is no indication that the system requires a full overhaul at present. The regime is highly valued by those taxpayers who utilise it and the Government does not propose to substantially change it.

The binding rulings regime was introduced in 1994-95 following the recommendation of the 1989–90 Tax Simplification Consultative Committee. The recommendation reflected the need for businesses to ensure that the tax consequences of a transaction are clear before a taxpayer makes a self-assessment, and that if Inland Revenue has given advice, that the advice will not change. This is particularly important when a business enters a large and complex tax arrangement.

The need for certainty is ongoing and will be particularly relevant in the modernised tax administration system. It is expected that the rulings regime will in the future be better co-ordinated with other forms of advice as both have a similar objective of enhancing certainty. As a first step towards Inland Revenue rationalising its advice products, the Government proposes to widen the scope of the rulings regime to make it more flexible, and make it more affordable for small and medium-sized enterprises.

The Government is proposing the following:

- Reduce the cost

The first proposal is to reduce the fees charged by Inland Revenue for providing a binding ruling. The key goal in reducing the fees would be to make binding rulings more accessible for small and medium-sized enterprises. Currently, private, product and status binding rulings all incur fees that are based on recovering some of the cost of providing the ruling. These include an application fee of $322 (GST inclusive) which covers the costs of receiving and reviewing the ruling application and a fee of $161 (GST inclusive) per hour spent by Inland Revenue considering the application and the issues it raises. This includes time spent consulting with the applicant. Inland Revenue’s costs in obtaining independent advice from external professionals are also passed on to the applicant (although this is rare).

The current rationale for charging fees is that the applicant receives the benefit of certainty about how Inland Revenue will apply the tax laws in relation to their situation. The applicant also gets priority of the Commissioner’s resources on their issue. If no fee were charged, taxpayers in general would effectively fund the benefit received by individual applicants. Charging a fee also ensures that only significant and serious applications for rulings are made.

However, the Government understands that the fees charged for rulings in New Zealand are a significant barrier to smaller businesses and individuals using the regime. Justice Susan Glazebrook recently raised the issue of whether the fees charged for binding rulings are consistent with the rule of law principle of equality before the law.[53]

A reduction in the fees would make it more affordable for small and medium-sized businesses and individuals to obtain certainty for important or complex transactions. The Government acknowledges there are still likely to be significant external costs for taxpayers in getting a ruling, being the likely costs for an advisor to prepare the ruling application and represent them in interactions with Inland Revenue. The application process places the obligation on the taxpayer to fully disclose the relevant facts and set out how the propositions of law apply to those facts. This is likely to mean that taxpayers will still only apply for rulings for significant transactions. A reduction in the fees would, however, be consistent with the overall goal of assisting taxpayers to get the initial assessment right. The reduction may also make it possible over time to remove the inefficient process of taxpayers issuing notices of proposed adjustments to their own self-assessments.

The Government has considered whether the proposed reduction in the fees could be achieved either by:

- A low flat application fee for all rulings

Having a single flat application fee would have low compliance costs for taxpayers and low administrative costs for Inland Revenue. A fixed fee also provides certainty for applicants as to cost for the ruling. However, a flat fee would not reflect the relative value of the benefits for a small enterprise as compared with a large company. Further, it will be difficult to set a fee level that reflects the benefits that large corporates get from a ruling, while not acting as a barrier to small and medium-sized enterprises. - A graduated schedule of application fees depending on the size or type of entity applying for the ruling (as in the United States)

Various elements may be relevant in determining the graduated schedule including the entity size and whether the entity is profit-driven. A graduated schedule will be able to more accurately reflect the benefit received by a specific applicant, making it fairer overall. The relevant elements have to balance the complexity of the issue with the value of the benefit received by an individual applicant. The more complex the schedule, the more likely it will be able to reflect the benefit received but also the more likely questions will arise about what fee will be appropriate in a given circumstance.

This document does not suggest a specific fee level but a significant decrease in fees is expected, at least for small and medium-sized enterprises. The current hourly rate fee would be removed.

The extent to which a reduction in fees will lead to an increase in the demand for rulings is unclear. When the rulings regime was first introduced, the fees were substantially lower and the demand was much greater than currently. However, some overseas experience suggests that the demand for rulings as a function of cost is fairly inelastic.[54] In the United States, recent academic papers suggest that the guaranteed awareness of a transaction by the revenue authority when a ruling is applied for is a significant reason why taxpayers may choose not to apply for a ruling (even if it is free), preferring instead to run the risk of being audited. Nevertheless, the Government acknowledges there is likely to be an increase in the base level of demand if fees are significantly reduced. Any increase in demand for rulings may require more resources to be devoted to providing rulings.

- Offer post-assessment rulings

As part of the move to advice being more rationalised, the second proposal is to allow post-assessment binding rulings. Currently, a ruling application cannot be made following an assessment. The reason for this prohibition was that post-assessment issues were seen to be the domain of the disputes process. The practical effect of the proposal would be to deliberately blur the boundary between a ruling and a dispute. The proposal would provide the right level of advice and certainty for a taxpayer, without being necessarily fixed on a particular advice product or process. It would reduce the time for a taxpayer to know the Commissioner’s opinion, when there is a discrete legal issue in dispute. Submissions are sought on how this proposal should fit in with the disputes review process. - Enhance the scope of rulings

The Government also proposes some extensions to the scope of the rulings regime:- Remove the prohibition on ruling on the purpose of a taxpayer under certain provisions.

- Relax the requirement that a ruling can only be issued on an “arrangement” but only to the extent of allowing the Commissioner to give certainty on some specific quasi-factual matters (such as whether a person is resident in New Zealand). The “arrangement” concept will be retained when ruling on transactions to reflect the relative complexity intended by the rulings regime.

- Clarify the connection between rulings and the financial arrangement rules determinations. This may allow the Commissioner to rule on certain matters rather than having to issue a determination. It may lead to completely replacing specific financial arrangement determinations with private or product rulings.

- Clarify the role of assumptions and conditions for rulings by setting out the differences between the two and when they should be used. This may also involve clarifying when a ruling no longer applies because a condition or assumption is breached.

Returns and information collection

Inland Revenue is considering the future of the return design process. New Zealand has one of the lowest disclosure requirements for tax returns in the world. Many jurisdictions require comprehensive information with the tax return to assist the tax authority. Often Inland Revenue sends targeted surveys to taxpayers to supplement tax return information. Inland Revenue’s Business Transformation programme provides an opportunity to revisit these information settings to see if these are still fit for purpose.

The Government considers the return process can be improved so that Inland Revenue obtains better information while reducing the compliance costs for taxpayers in providing the information. The returns processes will be considered as part of the work being undertaken for businesses and individuals.

Assessment

One of the key aspects of the assessment process is the time the assessment is made. Many aspects of the tax administration process turn on the date of the assessment. For example, a taxpayer’s dispute rights can start and end in relation to the date of the assessment.[55] The Government has considered whether the rules around the time of the assessment need to be updated as a result of the proposed changes to the assessment process.

Currently, the date on which the relevant return is filed is treated as the date the self-assessment is made.[56] The move to more electronic filing of returns, and a greater use of pre-populated returns, raises the issue of whether the rules relating to the timing of assessment need to be updated. The present approach requires taxpayers to consider the relevant facts and apply the law to those facts. Taxpayers may be required to verify the tax position by confirming a prepopulated return. The date on which the relevant return is confirmed will be treated as the date the self-assessment is made. Alternatively, if a taxpayer files a paper or electronic return the current timing rules will apply. As the same assessment process will apply in the digital environment only minimal changes need to be made to the timing rules.

As is currently the case, the filing of a return following a default assessment will be treated as a request for an amendment (or as a notice of proposed adjustment if the relevant criteria are satisfied). The original date of assessment will not change as a result of the filing of the return. In cases when the Commissioner issues a default assessment, as is currently the case, the date of the assessment will be the date the Commissioner makes the default assessment.

Amending an assessment

While the focus of the modernised tax administration is on getting the assessment right from the start, there are inevitably going to be situations when either the taxpayer or the Commissioner will seek to amend or correct the initial assessment. Correcting tax positions is an integral part of tax administration, and will continue to be so under the modernised tax administration system. Tax liabilities are as much about timing as quantum. It is important that, where practicable, tax be accounted for in the correct tax period.

Process for taxpayers to amend an assessment

The current process for taxpayers to amend an assessment was designed in the environment of paper returns and the limits of FIRST (Inland Revenue’s current computer system). The process can be resource intensive for both taxpayers and Inland Revenue, and involve significant delays. It imposes significant compliance costs on taxpayers and administration costs on Inland Revenue. There are different processes depending on the type of tax, the reason for the change, and the amount of the amendment. The different processes can be difficult for taxpayers to understand and easy for them to get wrong.

The key distinction between the different processes is whether the taxpayer:

- has to correct the original assessment, or

- is allowed to put the amendment in a subsequent return.

Income tax amendments: current law and practice

In general, amendments to income tax assessments need to be made to the original assessment (subject to an exception for minor errors discussed below). There are various ways that a taxpayer can seek an amendment to the original assessment:

- The taxpayer can file a notice of proposed adjustment (NOPA) to the assessment or default assessment within the required response period (generally up to four months after the date of the assessment). The filing of the NOPA commences the formal disputes process and means the Commissioner must consider the taxpayer’s proposed adjustment.

- The taxpayer can request that the Commissioner use her discretion to amend the original assessment (this may be by means of a voluntary disclosure). In this case, the Commissioner is not required to consider the merits of the proposed adjustment if she determines she does not have sufficient resources.[57] This means if the taxpayer does not file a NOPA within the response period, then the amendment may be made at the Commissioner’s discretion. There is uncertainty for taxpayers as to whether their tax position will be amended.

The Commissioner does not use her discretion in situations when there is uncertainty regarding the facts or the law (or both) as those situations should be dealt with under the disputes process.[58] Consistently with that, the Commissioner’s current approach is to only remedy genuine errors or underpayments of tax. Taxpayers reported that the process can be frustrating when the requested amendment is to their benefit. The aim of the modernised tax administration system is to be more flexible and adaptive. The approach of the Commissioner to amendments will need to reflect the new environment.

GST amendments: current law and practice

Additional processes apply for GST amendments. When a taxpayer has not claimed a GST deduction (input tax) in an earlier taxable period, they can claim that deduction in a later period.[59] However, if the taxpayer does not include GST to pay (output tax) in a return, the original assessment must be reopened to correct the tax position.

The Commissioner’s current approach is generally not to use her discretion to reopen a previous assessment to allow a taxpayer to claim a deduction, because they are able to claim it in a subsequent period. The approach is less clear when the taxpayer seeks to increase the amount of output tax for a specific period or to decrease the amount of an input tax deduction for a period. The approach is also more complicated when a taxpayer has omitted to return output tax for a period and to claim input tax for the same period. In those circumstances, the taxpayer may want to claim the input tax in the earlier period to offset or remove any liability for use-of-money interest for the increased output tax. As a result, there are different processes depending on the nature of the error.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that many taxpayers include errors involving both output tax and input tax in subsequent returns. This may reflect the complexity and the compliance costs of the process and the uncertainty for taxpayers about which process to follow.

Minor errors: current law and practice

Currently, there is a further option for remedying a minor error in an assessment for income tax, FBT or GST.[60] The option allows a taxpayer to include the minor error in a subsequent return.

The aim of allowing minor errors to be remedied in subsequent returns is to reduce tax compliance costs for small and medium-sized enterprises and individuals, although it applies to taxpayers generally.[61]

A minor error is one that is caused by a clear mistake, simple oversight, or mistaken understanding by the taxpayer. The total discrepancy caused by the minor error must be less than $500 for a single return.[62]

Putting the minor error in a subsequent return avoids the use of money interest that may apply if the original return is reopened. The option also avoids the compliance costs for the taxpayer of filing a separate notice to reopen the original assessment. However, the option means there can be a significant delay between identifying the error and providing certainty for the taxpayer. Delaying dealing with the error can create a risk for the taxpayer in that the amendment may exceed the threshold or not satisfy the criteria. This would mean it would have to be included in the original assessment. However, due to the delay in dealing with the issue, the taxpayer’s liability may have increased significantly.

Accounting treatment: current rules and practice

One of the goals of the “right from the start” framework is to align with the processes of the taxpayer rather than just requiring the taxpayers’ processes to fit into Inland Revenue’s processes. This suggests that, to the extent possible, the approach to remedying errors should align with the accounting approach.

However, for most taxpayers, including individuals, there will be no applicable accounting treatment for correcting errors. This means the process for remedying errors cannot align with an accounting treatment.

For those taxpayers required to use accounting standards, the requirements depend on the size of the entity and the nature of their operation. In broad terms, large or publicly accountable for-profit entities have to comply with the New Zealand equivalents to international financial reporting standards (NZ IFRS); large, non-publicly accountable, for-profit entities have to comply with New Zealand’s reduced disclosure regime (NZ IFRS RDR); and other small and medium-sized entities only have to comply with Inland Revenue’s special purpose reporting requirements. There is a similar scale of different reporting standards for public benefit entities.

Under the accounting standards, the general approach for material changes is to require the figures to be restated for the prior periods being disclosed as comparatives in the latest financial statements, including cumulative adjustments to any balances brought forward where relevant.[63] Materiality in accounting standards means a change that could influence the economic decisions that users make on the basis of the financial statements.[64] Materiality depends on the size and nature of the omission or misstatement judged in the surrounding circumstances. The size or nature of the item, or a combination of both, could be the determining factor. Anecdotal evidence suggests most corrections are made in the current period because they are considered not to satisfy the materiality threshold.

Compliance costs

The aim in making any change is to reduce the compliance costs for taxpayers of the amendment process. The current processes can impose significant compliance and administrative costs for relatively minor amendments.

Considerations

Various considerations have been taken into account in developing options, including:

- The right from the start framework

As discussed above, in accordance with the overall “right from the start” framework there should be as much consistency as possible with taxpayers’ existing processes, rather than requiring them to fit into Inland Revenue processes. - The relevant accounting treatment

To the extent possible, the requirements on taxpayers should reflect the materiality approach adopted in accounting standards. This suggests significant amendments need to be reflected in the previous period and minor amendments can be carried over to the current period. - Use of money interest

The fact the use of money interest regime reflects the time value of money is a consideration in designing rules for amendments to assessments. It is acknowledged that credit and debit use of money interest can apply to amendments. - Neutrality

A balance needs to be drawn between encouraging taxpayers to take care not to make errors in the initial assessment while recognising that even with due care mistakes will occur. There also needs to be fairness between taxpayers who diligently make correct assessments and those that are less diligent. - The allocation of resources

An aim needs to be to enable the Commissioner to allocate her limited resources to collect over time the highest net revenue that is practicable within the law, rather than focus on minor matters. - Benefits of start

The lower compliance costs of amending previous assessments under Inland Revenue’s new computer system (START) need to be taken into account.

Options

The Government is proposing amendments to the specific exemption for minor amendments. Two options are being considered:

- Remove the criteria

The first option is to remove the current criteria that determine when an amendment is minor, and instead rely solely on a monetary threshold. This would remove the need for determining whether an error is a clear mistake, simple oversight, or mistaken understanding by the taxpayer. - Supplement the monetary threshold

The second option is to supplement the single monetary threshold with an approach that relies in some way on the significance of the error to the taxpayer.

The Government proposes that the changes for minor amendments would apply for both income tax, FBT and GST. The exemption would not be mandatory and taxpayers could apply for a minor error to be included in the original assessment (rather than wait to put it in a subsequent return). This would provide earlier certainty for taxpayers. The exemption would not apply when the taxpayer had used the threshold for the main purpose of delaying the payment of tax.

Proposal: Supplement to the monetary threshold

The current threshold is proposed to be increased from $500 to $1,000 by the Taxation (Business Tax, Exchange of Information, and Remedial Matters) Bill. The $1000 limit represents a maximum adjustment of income or deductions of $3,571 for a company, $3,030 for an individual and $7,667 for GST.

The Government proposes supplementing the single monetary threshold with an approach that relies to some extent on the significance of the error for the particular taxpayer. This would allow taxpayers to include any error in a subsequent return if the amount of the error was equal to or less than both $10,000 and 2% of their taxable income or output tax for the relevant period (as appropriate). It would be optional for taxpayers.

Some benefits of the proposal are that it would:

- better align with the current practices of taxpayers, and the accounting treatment (where applicable)

- enable the Commissioner to allocate her limited resources to collecting over time the highest net revenue that is practicable within the law by better focusing on significant risks

- reduce compliance costs for taxpayers and administrative costs for Inland Revenue.

A materiality approach has been adopted in Australia for GST and the United Kingdom for VAT (see Appendix 1). Although it is arguable this is more appropriate given the frequency of GST or VAT returns, a similar approach may be equally relevant to income tax. The Government notes that the increasing reliance on withholding payments and the introduction of the accounting income method (AIM) diminishes the distinction in frequency of returns between income tax and GST.

Submitters’ views are sought as to whether the approach would appropriately balance the requirement to maintain integrity with the compliance costs of the amendment process (given the lower compliance costs under Inland Revenue’s new computer system (START)).

Process for the Commissioner to amend an assessment

The current process for the Commissioner to amend an assessment is:

- The Commissioner can file a notice of proposed adjustment to the assessment. The filing of the notice commences the formal disputes process.

- The Commissioner may make an amendment to the original assessment without issuing a notice of proposed adjustment in some circumstances.[65]

Withholding taxes

The discussion in this chapter on amending assessments relates to the core taxes. Consideration is also being given to whether the same approach should be adopted for amending returns for withholding taxes.[66] The most significant withholding tax is PAYE, which involves frequent filing. The Government has consulted on this (Making Tax Simpler: Better administration of PAYE and GST (November 2015)) and has recently announced its decisions in the light of the feedback received.

Payment of tax

The Government has recently introduced new options for the payment of tax, including increasing the scope of withholding payments and changes to provisional tax. The business tax proposals, contained in the Taxation (Business Tax, Exchange of Information, and Remedial Matters) Bill, include the proposed introduction of AIM, which may change the process for paying tax. Any future proposals to change the payment of tax will need to be aligned with the assessment process.

Disputes process

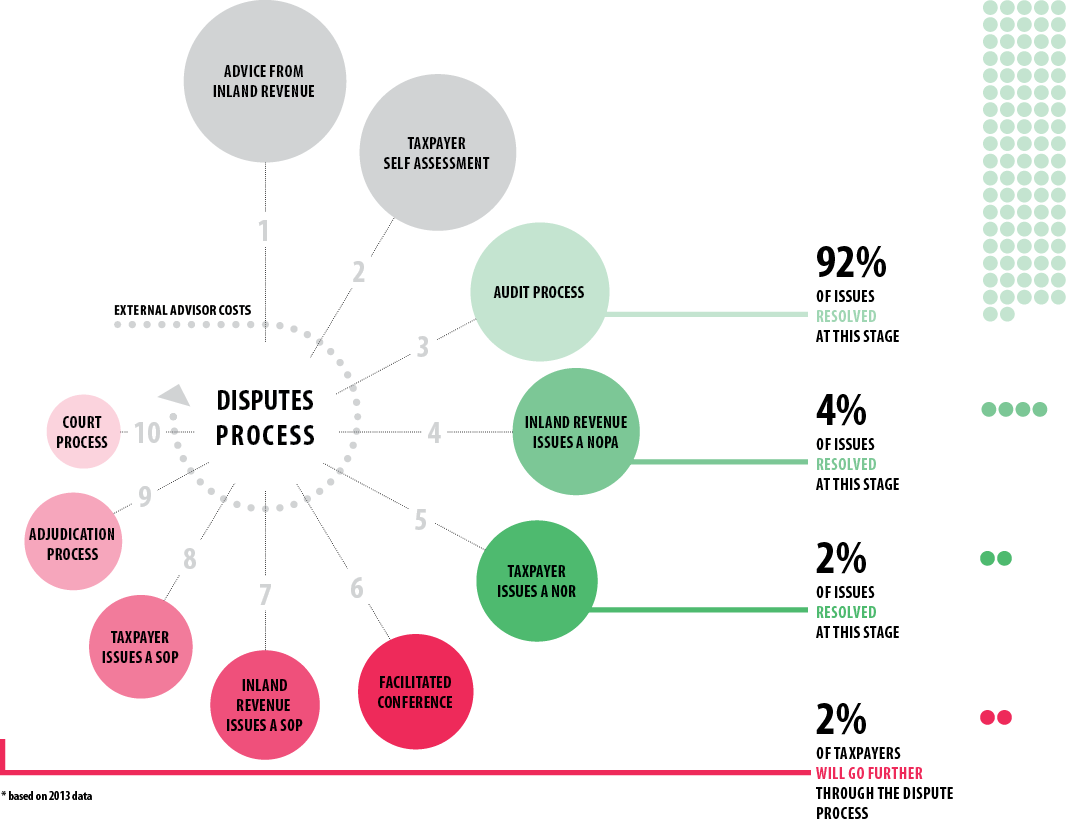

The disputes process originated from the findings of the Organisational Review of the Inland Revenue Department (the Richardson Committee).[67] The recommendations of the Richardson Committee were subject to a post-implementation review, the key aspects of which were included in the 2003 discussion document, Resolving tax disputes: a legislative review.[68] The disputes process was further considered in Disputes: a review (an officials’ issues paper, July 2010). Several administrative changes were made following the review in 2010 (such as facilitated conferences, shorter NOPAs and the truncation criteria).

One of the specific issues looked at during the 2010 review was the complaint that the disputes process can “burn-off” taxpayers (that is, discourage them from proceeding with the dispute because of the cost). The complaint was especially focused on small and medium-sized enterprises. There are no easy answers for reducing the costs of the disputes process because the disputes process deliberately demands engagement between taxpayers and Inland Revenue. Further, the process requires the identification of the facts and arguments to support understanding and resolution of the issue, and taxpayers will generally wish or need to be represented.

However, as the following table shows, the vast majority of issues are resolved before the formal disputes process and it therefore makes sense for Inland Revenue to first focus its organisational design thinking on the areas of highest demand. Therefore, the question of burn-off in the formal disputes process will be considered by Inland Revenue as it continues to develop the optimum approach to providing advice to taxpayers within its given resource constraints. Any changes to the disputes process can be considered at that time. The option (set out earlier in this chapter) to allow binding rulings following an assessment, including during the formal disputes process is, however, one measure to reduce burn-off.

Penalties

Because New Zealand’s tax system relies on self-assessment, rules are necessary to encourage taxpayers to file their tax returns on time, pay on time and take reasonable care in calculating their tax liabilities. For the system to work, it is vital that those who do not comply with the rules face consequences and are seen to do so. It is also important that the penalties that result when someone has not complied with the rules are in keeping with the severity of the offence and that there is a reasonable degree of certainty about when penalties will be imposed.

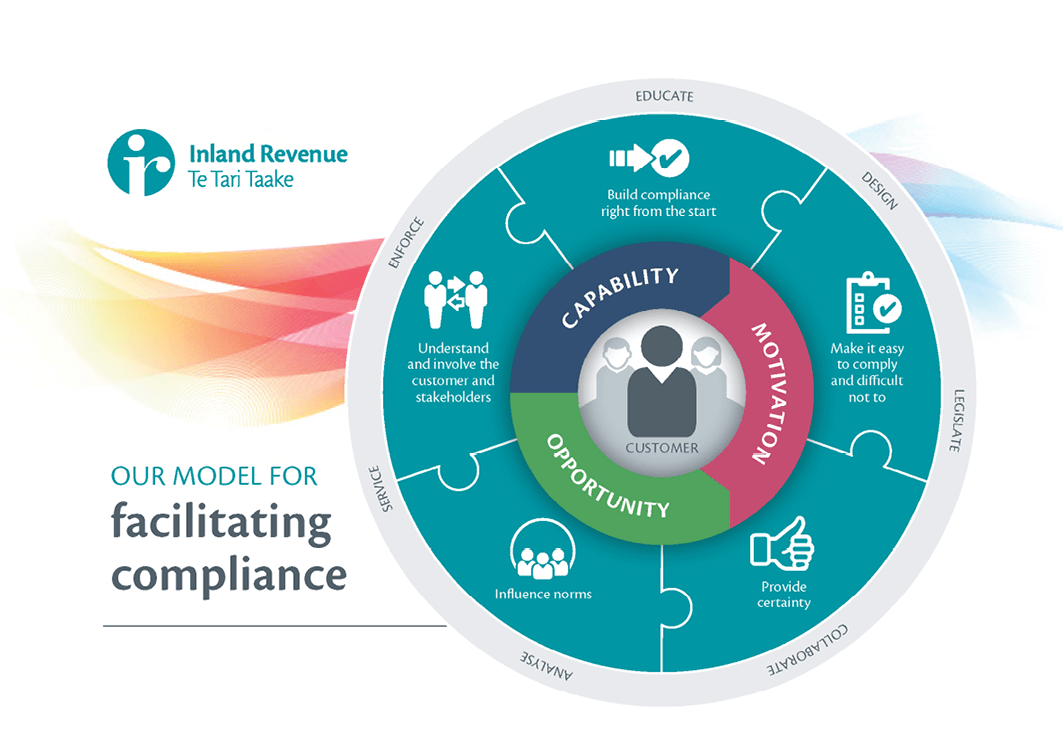

As noted in Towards a new Tax Administration Act, modernising the tax system provides an opportunity to recognise that taxpayer behaviour is about more than attitude. A combination of capability, opportunity and motivation make up compliance behaviour. Inland Revenue needs to think more widely about taxpayer needs and behaviours, and tailor activities depending on the causes of non-compliance. A review of the penalties regime is on the current tax policy work programme.

The penalties regime is based on encouraging taxpayers to:

- file their relevant returns (and so provide the Commissioner with the relevant information) through the use of late-filing penalties

- pay the taxing owing on time through the use of late payment penalties

- get their tax positions right through the use of shortfall penalties.

Late filing penalty

Currently, for most small and medium-sized taxpayers not filing a GST or income tax return on time would likely result in a one-off penalty of between $50 and $100. For many taxpayers, these amounts are insignificant, and once imposed, and there are no further penalties imposed to encourage the taxpayer to file.

The Government is considering a new late filing penalty that better encourages taxpayers to file their tax returns on time, while also being more proportionate to the potential harm of late filing. One of the options could be to set the penalty as a given percentage of the unfiled assessment, or a given amount that is imposed over a period of time, the longer the tax return remains overdue. It would be important to ensure the penalty does not become unreasonable (given the diverse size of various taxpayers), so the penalty may have minimum and maximum amounts.

Late payment penalty

The Government announced that the 1% monthly incremental late penalty is being removed from GST, provisional tax, income tax and Working for Families tax credit debt. The Government is considering whether to extend this to the remaining taxes and duties that currently incur the incremental late payment penalty (such as PAYE and FBT).

Late payment penalties can encourage payment on time. However, there is a point when the accumulated penalties and interest can overwhelm taxpayers, and any further penalties become ineffective at encouraging taxpayers to comply.

Inland Revenue currently imposes approximately 26% per annum on overdue tax debt in late payment penalties and interest. PAYE debt in particular can incur an even higher rate due to incurring other financial penalties as well. This relatively high rate can lead to some businesses quickly becoming deterred from proactively repaying their tax debt. The Government is considering options in this area.

Shortfall penalties

The shortfall penalty rules may need to be modernised to see whether they are still fit for purpose within a modern tax administration. There may be a need for more flexible rules that provide the Commissioner with greater discretion to not impose a penalty.

Certain parts of the shortfall penalty rules encourage taxpayers to follow particular processes and recognise some of the different causes of non-compliance:

- Advice: Taxpayers who rely on official opinions of the Commissioner are not subject to use-of-money interest or to shortfall penalties as a result of their reliance.

- Tax advisor: Taxpayers who use a tax advisor are deemed to have taken reasonable care in taking their tax position.

- Voluntary disclosure: If a taxpayer makes a voluntary disclosure, shortfall penalties can be substantially reduced.

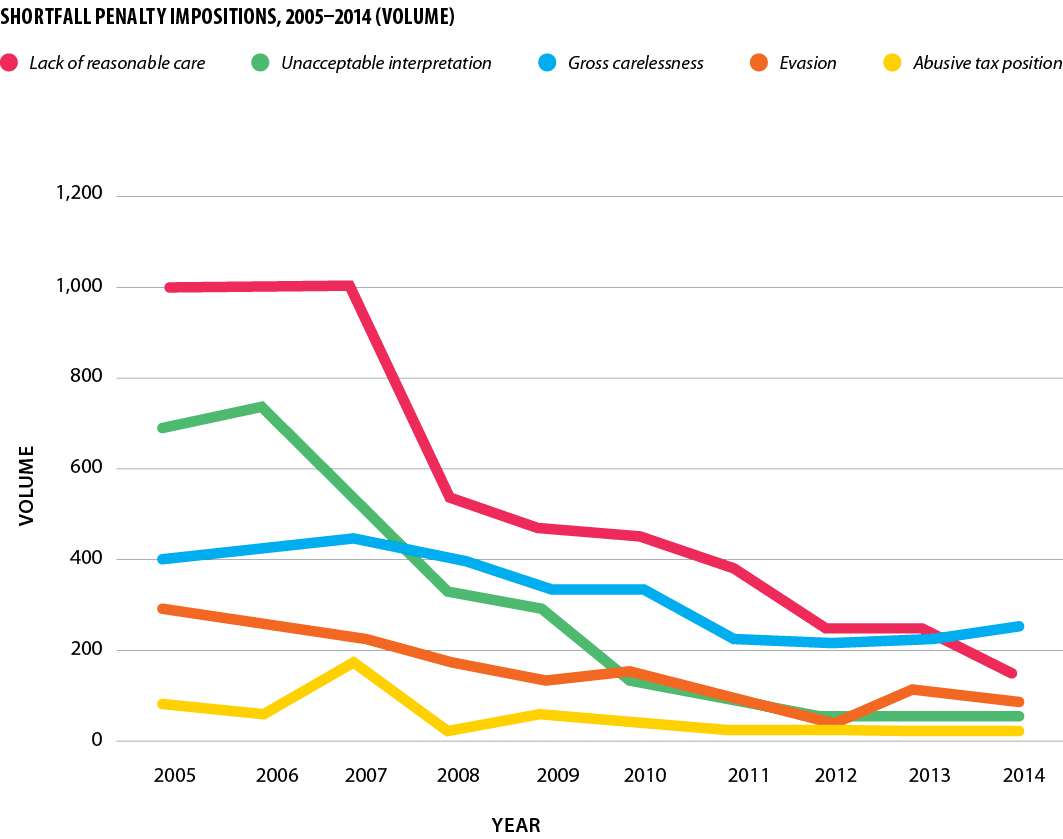

These elements mean that shortfall penalties are not imposed very often compared to the number of audit cases. In 2014 shortfall penalties were imposed in 570 audit cases out of a total of 9,862 closed audit cases (5.8%). The following graph shows the number of penalties that were imposed between 2005-2014:[69]

A greater number of small and medium-sized enterprises are using accounting software to manage their businesses. As part of Budget 2016, the Government announced that it would introduce AIM which allows taxpayers to pay their provisional tax based on a calculation prepared by accounting software.

The Taxation (Business Tax, Exchange of Information, and Remedial Matters) Bill proposes that taxpayers who use AIM are deemed to have taken an acceptable tax position for their provisional tax. This recognises that when a taxpayer uses AIM any non-compliance is not due to their motivation, so a penalty will not assist with compliance.

Further integration between accounting software and Inland Revenue’s systems and processes has been requested by taxpayers. The government will consider options for greater integration, including whether any further changes are needed to shortfall penalties as a result of greater integration or to better align shortfall penalties with the new compliance framework.

Record keeping

The way people keep records is changing with the growth in electronic record keeping and cloud-based storage. The Government considers it is prudent to take a look at the record keeping rules and the relevant penalties to see whether these rules are fit for purpose.

[45] Right from the Start: Influencing the Compliance Environment for Small and Medium Enterprises (OECD, January 2012) 3.

[46] Right from the Start (January 2012) 3.

[47] Right from the Start (January 2012) 3.

[48] See Making Tax Simpler – A Government Green Paper on Tax Administration (March 2015) 41.

[49] Sections 120W and 141B. It is noted the exclusion from the application of shortfall penalties does not apply to the evasion penalty.

[50] See Status of Commissioner’s Advice (http://www.ird.govt.nz/technical-tax/commissioners-statements/status-of-commissioners-advice.html).

[51] For the last fiscal year (2015/16) Inland Revenue calculated that it ruled on at least $17 billion worth of transactions, involving at least $3 billion worth of tax at issue.

[52] See definition of “Commissioner’s official opinion” in section 3 of the Tax Administration Act 1994.

[53] Address to 2015 CAANZ Tax Conference, November 2015.

[54] Yehonatan Givati Resolving legal uncertainty: the unfulfilled promise of advance tax rulings (2009) Virginia Tax Review) 137.

[56] Legislating for self-assessment of tax liability (Government Discussion Document, August 1998) [3.14].

[57] See Standard Practice Statement SPS 16/01: Requests to amend assessments.

[58] See Standard Practice Statement SPS 16/01: Requests to amend assessments.

[59] Section 20(3). The ability to include it in a subsequent return is subject to some conditions.

[60] Excluding the possibility of issuing a notice of proposed adjustment.

[61] See the commentary to the Taxation (Consequential Rate Alignment and Remedial Matters) Bill 2009.

[62] The current threshold is proposed to be increased to $1,000 by the Taxation (Business Tax, Exchange of Information, and Remedial Matters) Bill.

[63] See NZ IAS 8 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors.

[64] See NZ IAS 1 Presentation of Financial Statements.

[65] Section 89C of the Tax Administration Act 1994.

[66] There is generally no assessment when a withholding tax return is filed. The Commissioner has the ability to issue an assessment but rarely does.

[67] Organisational Review of the Inland Revenue Department, Report to the Minister of Revenue (and on tax policy, also to the Minister of Finance) from the Organisational Review Committee, April 1994, Chapter 10.

[68] Resolving tax disputes: a legislative review, a government discussion document first published in July 2003.

[69] See http://www.ird.govt.nz/aboutir/audit-and-legal-issues/shortfall-penalty/shortfall-penalty-impositions.html