Chapter 2 - Hybrid mismatch arrangements

2.1 A “hybrid mismatch arrangement”, as defined by the OECD:[6]

… exploits a difference in the tax treatment of an entity or instrument under the laws of two or more tax countries to produce a mismatch in tax outcomes where the mismatch has the effect of lowering the aggregate tax burden of the parties to the arrangement.

2.2 Thus, a taxpayer with activities in more than one country may have opportunities to escape taxation through the use of hybrid mismatch arrangements.

2.3 In the vast majority of cases, the tax outcome comes from a mismatch of domestic laws. However, double tax agreements can be used to enhance a tax benefit (for example, via the elimination or reduction of withholding taxes at source). The use of hybrid mismatch arrangements puts the collective tax base of countries at risk, although it is often difficult to determine which individual country has lost tax revenue under an arrangement.

2.4 Action 2 of the OECD Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) calls for domestic rules targeting mismatches that rely on a hybrid element to produce the following three tax advantage outcomes:[7]

- Deduction no inclusion (D/NI): Payments that give rise to a deduction under the rules of one country but are not included as taxable income for the recipient in another.

- Double deduction (DD): Payments that give rise to two deductions for the same payment.

- Indirect deduction no inclusion (indirect D/NI): Payments that are deductible under the rules of the payer country and where the income is taxable to the payee, but offset against a deduction under a hybrid mismatch arrangement.

2.5 The mismatches targeted are those arising in the context of payments as opposed to, for example, a mismatch arising from rules that allow a taxpayer “deemed” interest deductions for equity capital.

2.6 In broad terms, hybrid mismatch arrangements can be divided into the following categories based on the particular hybrid technique that produces the tax outcome:

- Hybrid instruments exploit a conflict in the tax treatment of an instrument in two or more countries. These arrangements can use:

- Hybrid financial instruments, under which taxpayers take mutually incompatible positions regarding the treatment of the same payment under the instrument;

- Hybrid transfers, under which taxpayers take mutually incompatible positions regarding who has the ownership rights in an asset; or

- Substitute payments, under which a taxable payment in effect becomes non-taxable by virtue of a transfer of the instrument giving rise to it.

- Hybrid entities exploit a difference in the tax treatment of an entity in two or more countries (generally a conflict between transparency and opacity).

2.7 Hybrid entities and instruments can be embedded in a wider arrangement or structure to produce indirect D/NI outcomes.

Hybrid instruments

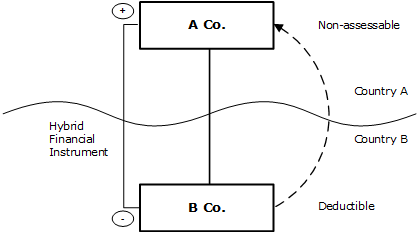

Hybrid financial instruments

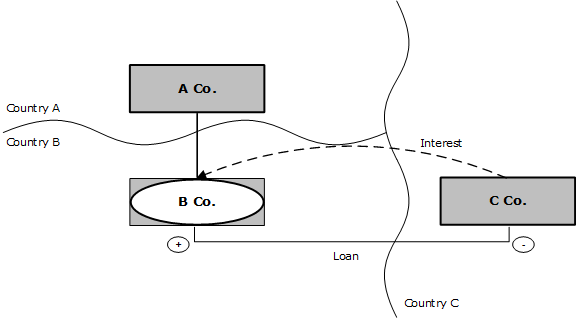

2.8 A simple arrangement involving the use of a hybrid financial instrument is set out below.

Figure 2.1: Hybrid financial instrument[8]

2.9 Under the arrangement, B Co (resident in Country B) issues a hybrid financial instrument to its parent A Co (resident in Country A). Country B treats the instrument as debt, so that payments under the instrument are treated as deductible interest to B Co. Country A treats the instrument as equity, so that payments under the instrument are treated as exempt dividends (or otherwise tax relieved) to A Co. The tax outcome is D/NI.

2.10 A number of New Zealand taxpayers have had recent involvement in tax avoidance litigation with the Commissioner of Inland Revenue regarding their use of hybrid financial instruments in funding arrangements with their offshore parents.

2.11 In Alesco New Zealand Ltd v Commissioner of Inland Revenue,[9] the New Zealand Court of Appeal considered one such arrangement as a test case. The New Zealand taxpayer had issued optional convertible notes to its Australian parent; treated as part debt and part equity in New Zealand, but exclusively equity in Australia. Outside of tax avoidance, the tax outcome was D/NI: a New Zealand deduction for the interest notionally paid by the New Zealand taxpayer on the debt component of the notes,[10] but no interest income to the Australian parent for which it would otherwise have been liable for Australian taxation. The Court of Appeal’s holding that the arrangement was tax avoidance was not based on the Australian tax treatment.

2.12 Apart from taxpayers formally bound by the Alesco ruling, a number of New Zealand taxpayers have, in recent times, entered into arrangements under which they have issued mandatory convertible notes (MCNs) to their offshore parents. Commonly, interest is accrued over the term of the arrangement, and at maturity, the issuer’s interest obligation is satisfied by issuing shares. As New Zealand treats the MCN as debt, the arrangement gives rise to deductible interest to the New Zealand issuer,[11] but the issue of shares to satisfy the New Zealand issuer’s interest obligation does not result in income to the offshore parent (that is, D/NI).

2.13 The Commissioner has challenged a number of the arrangements using MCNs as tax avoidance arrangements. Under recent Australian domestic rule changes, a D/NI outcome can potentially now be achieved using an MCN with cash interest payments. Previously, Australia’s non-portfolio foreign dividend exemption would not have applied had cash interest (rather than the issue of shares) been paid under the MCN, because an MCN is not legal form equity.[12] Now, such payments would likely be exempt in Australia;[13] the amendments ensure that Australia’s non-portfolio foreign dividend exemption applies to returns on instruments that are legal form debt but that Australia characterises as equity, as a matter of substance, under its debt-equity rules.[14]

2.14 A third common form of trans-Tasman hybrid financial instrument is frankable/deductible instruments issued by the New Zealand branch of some Australian banks to the Australian public.[15] Typically, these instruments qualify as bank capital for Australian regulatory purposes. As with the MCNs, the bank issuer claims a New Zealand tax deduction for the coupon on these instruments. The Australian tax treatment is different. The instruments are treated as equity for Australian tax purposes, but because they are held by portfolio investors, the return is taxable. However, the bank attaches franking credits to the coupon. The credits work in the same way as New Zealand imputation credits. The credits are not generated by the investment of the funds raised by issue of the instruments – because that income is earned by the New Zealand branch of the Australian bank it is not subject to Australian income tax. So the Australian bank obtains a New Zealand income tax deduction for a payment which for Australian tax purposes is treated in the hands of the payee as made out of fully (Australian) taxed income.

2.15 This type of instrument is considered in Example 2.1 of the Final Report, which concludes that it gives rise to a hybrid mismatch.

Hybrid transfers

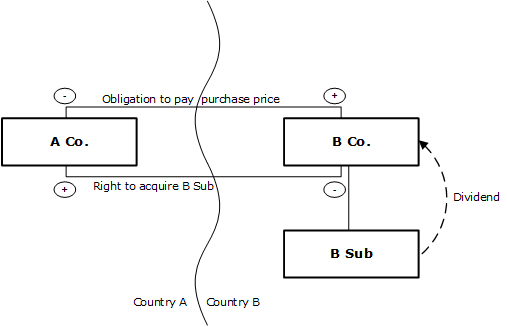

2.16 A simplified arrangement involving a hybrid transfer is set out in Figure 2.2.

2.17 Typically, a hybrid transfer is a collateralised loan arrangement or share lending transaction where the counterparties in different countries are each treated for tax purposes as the owner of the loan collateral or subject matter of the share loan. In the arrangement set out in the figure below, the mismatch arises because Country A taxes the arrangement in accordance with its economic substance (a loan with the shares as collateral), while Country B (like New Zealand) taxes in accordance with the arrangement’s legal form (a sale and repurchase or “repo” of the shares).

Figure 2.2: Hybrid transfer – share repo[16]

2.18 A Co (resident in Country A) owns B Sub (resident in Country B). A Co sells its B Sub shares to B Co under an arrangement that A Co will reacquire those shares at a future date for an agreed price reflecting an interest charge reduced by any dividends B Co receives on the B Sub shares. Between sale and repurchase, B Sub pays dividends on the shares to B Co. In Country A, A Co is treated as receiving these dividends and paying them to B Co as a deductible financing cost. In Country B, B Co is treated as receiving the dividends, which are tax exempt. The tax effect is D/NI.

Hybrid entities

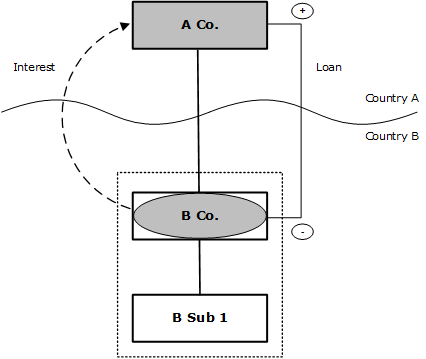

Disregarded payments made by a hybrid payer

2.19 A simplified arrangement involving the use of a hybrid entity to achieve a D/NI outcome is set out in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: Disregarded payments made by a hybrid entity[17]

2.20 A Co (resident in Country A) indirectly holds B Sub 1 (resident in Country B) through B Co, a hybrid entity treated as transparent in Country A, but opaque in Country B. B Co borrows from A Co, and pays interest on the loan, which is treated as deductible in Country B. The deduction can be used to offset income in B Sub 1’s group of companies in Country B. As Country A treats B Co as transparent (and as A Co is the only shareholder in B Co), the loan, and interest on the loan, between A Co and B Co, is disregarded in Country A (that is, a D/NI result).[18]

2.21 New Zealand unlimited liability companies are used to play the role of B Co in the figure above to achieve a D/NI (inbound) outcome. The United States’ domestic “check the box” rules allow a New Zealand unlimited liability company, treated as opaque by New Zealand, to be treated as transparent for United States income tax.

2.22 The creation of a permanent establishment in the payer country can be used to achieve a similar D/NI outcome. For example, a subsidiary company resident in an overseas jurisdiction could borrow from its parent company resident in the same jurisdiction. If the subsidiary allocates the loan to a New Zealand branch, the interest paid on the loan would be treated as deductible in New Zealand (but subject to New Zealand non-resident withholding tax). However, a tax consolidation of the subsidiary with its parent would mean that the interest payment is disregarded in the overseas jurisdiction.

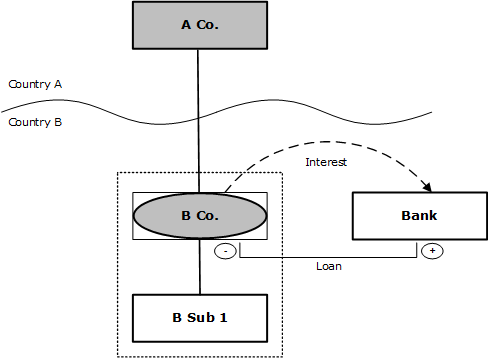

Deductible payments made by a hybrid payer

2.23 A simplified arrangement using a hybrid entity to achieve a DD outcome is set out in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4: DD arrangement using hybrid entity[19]

2.24 Under the arrangement, A Co (resident in Country A) owns all the shares of B Co (resident in Country B). B Co borrows from the bank and pays interest on the loan, deriving no other income. As Country A treats B Co as transparent, A Co is treated as the borrower by Country A. However, as Country B treats B Co as opaque, B Co is treated as the borrower by Country B. The result is a deduction for the interest expenditure in Country A and B (that is, a DD outcome). If B Co is consolidated for tax purposes with its operating subsidiary B Sub 1, B Co can surrender its tax deduction to B Sub 1, allowing two deductions for the same interest expense to be offset against separate income arising in Country A and Country B.

2.25 Australian limited partnerships (treated as transparent in New Zealand, but opaque in Australia) are used to achieve an outbound DD result in essentially the manner described in the example above.[20]

2.26 As with D/NI, the creation of a permanent establishment in the payer country can be used to achieve a similar DD outcome, if the income and expense of the permanent establishment is eligible to be consolidated or grouped for tax purposes in that country.

Reverse hybrids

2.27 A simplified arrangement using a reverse hybrid is set out in Figure 2.5. A reverse hybrid is a hybrid entity that is treated as opaque by its foreign investor, but transparent in the country of its establishment (in the reverse of the examples described above).

Figure 2.5: Payment to a reverse hybrid[21]

2.28 A Co (resident in Country A, the investor country) owns all the shares in B Co, (the reverse hybrid established in Country B, the establishment country). Country B treats B Co as transparent, but Country A treats B Co as opaque. C Co (resident in Country C, the payer country) borrows money from B Co and makes interest payments under the loan. The outcome is D/NI if the interest paid by C Co is deductible in the payer country (Country C), but not included as income under the domestic rules of either the investor or establishment country (Country A or B), because each country treats the income as having been derived by a resident of the other country, and Country B does not treat the income as sourced in Country B.

2.29 Controlled foreign company (CFC) rules in the investor country that tax the income of residents earned through CFCs on an accrual basis would eliminate such mismatches. However, New Zealand’s CFC rules contain an active income exemption as well as a safe harbour, under which passive income is not subject to accrual taxation if it is less than 5 percent of total income.

Indirect outcomes

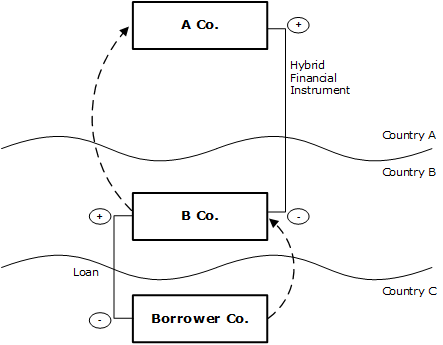

2.30 The effect of a hybrid mismatch that arises between two countries can be imported into another country to create an indirect D/NI outcome, if the first two countries do not have hybrid mismatch rules. An example of this is set out in Figure 2.6.

Figure 2.6: Imported mismatch from hybrid financial instrument[22]

2.31 A Co lends money to B Co, a wholly owned subsidiary of A Co, using a hybrid financial instrument, so that payments under the instrument are exempt in Country A, but deductible in Country B. Neither Country A nor Country B has hybrid mismatch rules. Borrower Co then borrows from B Co. Interest payable under the loan is deductible in Country C (Borrower Co’s country of residence) and taxable income in Country B. The result is an indirect D/NI outcome between Countries A and C (Country B’s tax revenue is unaffected as the income and deductions of B Co are offset).

2.32 It is difficult for tax investigators to detect imported hybrid mismatches, as detection requires a broad understanding of a taxpayer group’s international financing structure. This information is often not publicly available, and can be difficult to obtain from the New Zealand taxpayer. However, if a country were to introduce hybrid mismatch rules without a rule against imported hybrid mismatches that could allow some taxpayers to seek to exploit that gap. This would be against the intended outcome of the rules which is that the tax advantages of hybrid mismatches are neutralised, leading taxpayers to, in most cases, adopt more straightforward cross-border financing instruments and structures.

6 OECD 2014 Interim Report at para 41.

7 OECD 2015 Final Report at para 6.

8 OECD 2014 Interim Report at p33.

9 Alesco New Zealand Ltd v Commissioner of Inland Revenue [2013] NZCA 40, [2013] 2 NZLR 175.

10 With no New Zealand non-resident withholding tax (NRWT) liability.

11 And no New Zealand NRWT obligation.

12 Section 23AJ of the Australian Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 – repealed under item 1 of Part 1, Schedule 2 to the Tax and Superannuation Laws Amendment (2014 Measures No. 4) Act 2014.

13 Although prima facie subject to New Zealand non-resident withholding tax.

14 The Tax and Superannuation Laws Amendment (2014 Measures No. 4) Act 2014 received Royal assent on 16 October 2014. The relevant provisions apply the day after Royal assent: section 2 and Part 4 of Schedule 2.

15 See Mills v Commissioner of Taxation [2012] HCA 51.

16 OECD 2014 Interim Report at p35.

17 OECD 2014 Interim Report at p42. The tax outcomes of the arrangement are described at paras 73–74. This structure is also at the core of Example 3.1 of the OECD 2015 Final Report at p288.

18 The treaty implications relate to whether, and to what extent, Countries A and B are limited by the relevant treaty in taxing the income of A Co. Under the OECD Model, an amount arising in Country B is paid to a resident of Country A, so, prima facie, the benefits of Article 11 (Interest) would be granted.

19 OECD 2014 Interim Report at p51.

20 The Australian limited partnership (ALP) would have an Australian-resident partner and a New Zealand-resident partner, but the New Zealand-resident partner could hold up to 99.99 percent of the ALP in order to maximise the tax advantage (the DD outcome).