Repeal of KiwiSaver kick-start payment

Agency Disclosure Statement

1. This regulatory impact statement has been prepared by the Treasury in consultation with Inland Revenue.

2. It was prepared following a request from the Minister of Finance to provide advice on options to reduce the fiscal cost and improve the target effectiveness of the KiwSaver scheme and in particular explore the removal of the $1,000 kick-start payment paid to all new enrolees in the scheme. The advice was requested in advance of Budget 2015 and therefore has been prepared urgently.

3. The analysis in this statement has been prepared following the completion of the Inland Revenue-led KiwiSaver Evaluation and relies on its findings.

4. The analysis has not focussed on the effect of policy options on national saving as was the case with the KiwiSaver policy changes announced with Budget 2011. Instead, the analysis is concerned with addressing the poor value for money and target effectiveness (leakage) of KiwiSaver subsidies.

5. There has been only limited consultation because of Budget sensitivity and a likely behavioural response. The KiwiSaver Evaluation is the best available evidence (including evidence from focus groups and empirical study) of the efficiency and effectiveness of the scheme and it is unlikely that public consultation would provide further insights.

James Beard

Manager, Financial Markets

The Treasury

6 May 2015

Executive summary

6. The recent Inland Revenue Evaluation finds that KiwiSaver is a very costly voluntary savings scheme which has not substantially increased savings despite encouraging enrolment of a large number of individuals. This regulatory impact statement analyses the options for changes to KiwiSaver policy settings, the forecast fiscal savings and likely behavioural responses.

7. The options to reduce fiscal cost (and therefore increase the value for money of the scheme) involve reducing or removing the subsidies: the $1,000 kick-start payment and/or the annual member tax credits. Options to address target effectiveness of the scheme – increasing the extent to which KiwiSaver encourages additional saving among those who would otherwise face a diminution of living standards in retirement - are more difficult.

8. This regulatory impact statement addresses these options and concludes that the choice to change KiwiSaver subsidies depends on Ministers relative prioritisation of competing fiscal demands and encouraging saving in the scheme.

Status quo and problem definition

9. The KiwiSaver scheme currently costs around $800 million in subsidies per annum and the Government has spent in excess of $6 billion on it since inception in 2006. There are currently two subsidies: a one-off $1,000 kick-start payment paid to all new enrolees in the scheme (the kick-start) and an annual member tax credit paid to members of up to a maximum of $521 (annual MTC). The scheme also has ongoing Inland Revenue administration costs.

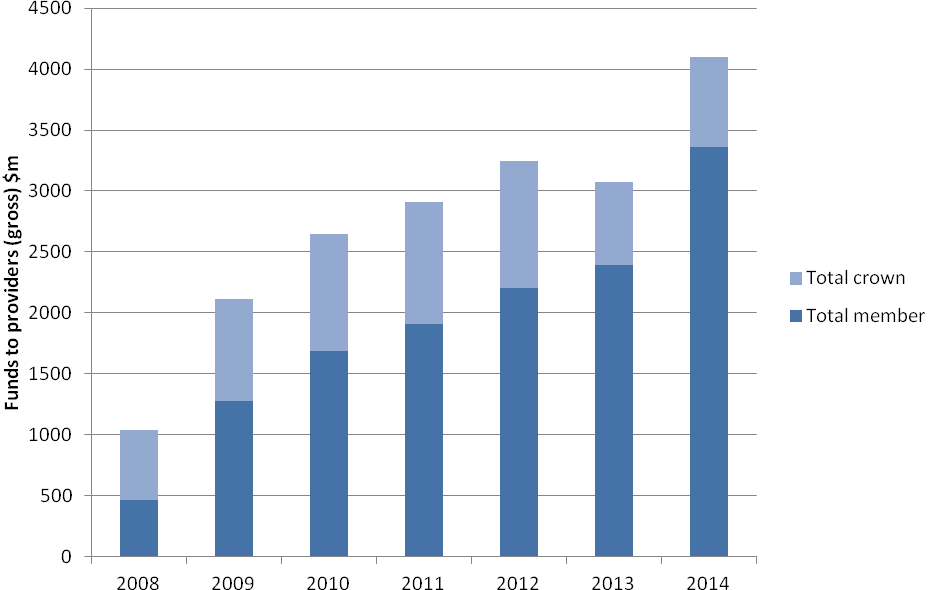

10. A seven year evaluation of KiwiSaver concluded in 2014 (the Evaluation) and the Evaluation reports will be published soon (we expect in line with Budget 2015). The Evaluation has broadly found that the scheme has been successful in attracting significant numbers of members and Inland Revenue’s role in the scheme has functioned well. However, the scheme has delivered very poor value for the Crown’s subsidies. A high degree of leakage to people outside the target group for KiwiSaver and substitution from other savings has occurred. Estimates range from zero to one-third of KiwiSaver balances representing new household savings. It should be noted that the maximum annual MTC has already been halved from its original level together with other changes to KiwiSaver with Budget 2011 and this improved the value for money of the scheme. Figure 1 below illustrates the changes in contributions to KiwiSaver accounts.

Figure 1: KiwiSaver contributions, 2008-2014 (June years)

Source: Statistics NZ

11. The Minister of Finance requested that the Treasury provide some options for changes to KiwiSaver to reduce headline costs to the Crown and to reduce the degree of leakage.

Objectives

12. The objectives for any changes to KiwiSaver policy settings are to:

a. Improve the value for money of the KiwiSaver scheme and reduce the headline costs to help achieve the Government’s fiscal objectives; and

b. Improve the target effectiveness of the KiwiSaver scheme (i.e. reduce the leakage to non-target individuals) without discouraging increased levels of private household savings and a long-term savings habit among the target population of the KiwiSaver Act.

13. The KiwiSaver Evaluation highlighted the success of the administrative simplicity of the scheme. It broadly concluded that the Inland Revenue’s role as a clearing house for contributions and the administrative design and interplay between members, employers, Inland Revenue and providers had been a major contributing factor to the large degree of uptake. Likewise, the automatic enrolment features of the scheme have been effective at ensuring high rates of enrolment among salary and wage earners. Therefore, an objective is to retain the principal administrative features of KiwiSaver.

14. There is a timing constraint as the Minister of Finance aims to achieve these objectives with the passing of Budget 2015.

Background Policy Considerations

Difficulties in defining the target population for KiwiSaver for “value for money”

15. The value for money of KiwiSaver policy is a measure of how much it costs the Government to prompt an additional dollar of savings from the target population. Value for money is related to the degree of leakage from payment of the Crown subsidies to individuals outside of the target population.

16. Assessing value for money is difficult due to the imprecision inherent in the wording of the purpose in section 3 of the KiwiSaver Act. That purpose refers to boosting savings among

“individuals who are not in a position to enjoy standards of living in retirement similar to those in pre-retirement”.

17. The target population of KiwiSaver is thus a sub-set of individuals aged 18-64; children and those who have reached the eligibility age for New Zealand Superannuation (65) are outside. However, it is not possible to identify this sub-set by reference to income bands or employment status (or other measures commonly used to define eligibility for Government support). In order to overcome this problem, the value for money analysis in the Evaluation is based on the self-reporting by respondents to surveys conducted by Colmar Brunton in 2010 and 2014 and is also based on the methodology in a Treasury Working Paper by Law, Meehan, Scobie (2011).

Difficulties in addressing leakage

18. In order to assess whether KiwiSaver had successfully helped the target group, two conditions had to be satisfied (which were the best proxies available for the stated purpose of section 3 of the KiwiSaver Act).

19. First, the individual in question had to have reported an expected retirement income shortfall, measured as the difference between the annual income they said they expected to have in retirement (the median was $35,000) and that which they said they would need to meet their basic needs (the median was $33,000). Only 20% of KiwiSaver members had an expected retirement income shortfall. The proportion of non KiwiSaver members who reported an expected retirement income shortfall was similarly low, at 24%.

20. Law, Meehan and Scobie (2011) undertook regression analysis to try and identify factors associated with the levels of individuals’ expected retirement income shortfalls (or excesses). The key result was that only two factors were associated with a reduced likelihood of reporting an expected retirement income shortfall. These were having higher income, or being a non salary / wage earner (i.e. being self employed, unemployed or not in the labour force). In both cases, however, the relationship is weak. These two factors are far from being perfect predictors of whether or not a KiwiSaver member belongs to the target group.

21. The second necessary condition was that upon joining KiwiSaver that individual had to substantially increase their savings as a result. In particular more than 30% of an individual’s contributions to KiwiSaver had to represent additional savings. Only a third of individuals who reported a retirement income shortfall met this additional condition.

22. Only 7% of KiwiSaver members met these two conditions and therefore belonged to the programme’s target group.[1] 93% of KiwiSaver members did not meet one or both conditions so are described as contributing to leakage from the scheme.

23. The figure for leakage of 43% which Inland Revenue have used in their Value for Money report in the Evaluation (but sourced from Law, Meehan and Scobie (2011)) relaxes the first of these two conditions. In particular, rather than calculating expected retirement income shortfalls based on the annual income individuals said they would need to meet their basic needs, the calculation uses the higher level of income individuals said they would need to be comfortable (the median was $45,000).

24. Regardless of definition much of the following logic applies: For a policy change to improve leakage, at least one of three things would be required.

a. First, more people could be somehow caused to have an expected retirement income shortfall. However, this is obviously not desirable.

b. Second, the extent to which KiwiSaver generates additional saving would need to increase. It is not at all clear how this could be achieved and indeed recent evidence (Law and Scobie (2014)) suggests KiwiSaver may not be delivering any additional savings amongst members on average.

c. This leaves reducing membership of KiwiSaver amongst individuals who do not report an expected retirement income shortfall (80% of members). To achieve this would require being able to easily identify these people. However, this would be extremely difficult given the aforementioned inability to define the target population for KiwiSaver using conventional socio-economic metrics or identifiers (such as income).

Targeting measures to improve leakage is difficult

25. Even if KiwiSaver membership were restricted to those on relatively low incomes or only salary and wage earners, we would not expect to see a substantial improvement in leakage. Furthermore, such changes would add to the complexity of the scheme, which would undermine the success of the administration of KiwiSaver as identified in the Evaluation. Therefore implementing targeting measures which improve leakage is difficult.

Available Options

26. We therefore look below at measures to improve the value for money of the scheme by reducing its costs.

27. The options available to improve value for money include to:

a. Remove the kick-start or reduce its scope or generosity; and/or

b. Remove the annual MTCs or reduce the scope or generosity.

28. A more fundamental review of the purpose in section 3 of the KiwiSaver Act to address the aforementioned problems arising from the imprecise definition of a target population would be officials’ preferred option. However, this option is not within the scope of the present exercise which was to identify measures to improve KiwiSaver effectiveness in light of the Evaluation and reduce fiscal cost.

29. The option analysis in the following uses forecasts of KiwiSaver enrolments (and the associated fiscal cost of subsidies) provided by Inland Revenue. The fiscal savings from the available options are shown in illustrative examples in table 1 below:

| Option | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KickStart | |||||

| Removed | 17 * | 175 | 126 | 106 | 107 |

| Removed for under 18s | 2 * | 28 | 13 | 13 | 12 |

| Member Tax Credit | |||||

| Removed | - | 709 | 756 | 795 | 832 |

| Halved** | - | 339 | 362 | 381 | 399 |

*Assuming a Budget next-day effective date

**Assuming half of the non-salary-and-wage-earners left KiwiSaver or took contribution holidays after the policy change and the same proportion of dollar amount saved in 2014/15 applies to pre-reduction forecasts in subsequent years.

Remove or reduce the generosity of the kick-start

30. A removal of the kick start would save fiscal costs which, under present policy settings and given present trends in KiwiSaver membership, are expected to be $175m in 2015/2016 falling to $107m by 2018/19. By reducing the headline cost of the scheme, the value for money of the policy would be improved (as set out below).

31. The removal of the kick-start would reduce the attractiveness and enrolment rate into KiwiSaver by the self-employed. Regression analysis in Law, Scobie and Meehan (2011) also found that the self-employed are less likely to fall within the target population of the KiwiSaver Act, however, that relationship is weak. Therefore, removal or reduction of the kick-start may marginally improve the target effectiveness.

32. The behavioural response from salary and wage earners would likely be lower than for the self-employed because for many salary and wage earners, the greater incentive for joining KiwiSaver is related to the employer contributions of minimum 3% of gross income in addition to ongoing annual MTCs. Therefore removal or reduction of the kick-start would reduce fiscal costs without reducing savings rates, thus increasing value for money.

Change the scope of eligibility for the kick-start – under-18s not eligible

33. Removal of the kick-start altogether for those under-18 years of age would reduce the headline cost and therefore improve value for money. This option would also improve target effectiveness because under-18 year olds are outside of the target group for the policy. Assuming that this simply delays the point at which people join (i.e. someone who would have joined in 2015 when aged 16 will now join in 2017 when they turn 18) this option generates estimated annual fiscal savings of $28m in 2015/16 falling to $12m in 2018/19.

Remove or reduce the generosity of the annual MTCs

34. Removing the annual MTCs completely would save fiscal costs which, under present policy settings and given present trends in KiwiSaver membership, are expected to be $709m in 2015/16 rising to $832m in 2018/19.

35. These estimates take account of the current distribution of annual MTCs and include a behavioural response (ceasing making contributions) from those people with no salary or wage income such as the self-employed.

36. No reduction in contributions to the scheme (which would include a reduction in contributions, increases in members taking contribution holidays or a reduction in enrolment) by salary and wage earners is assumed as a result of removing (or reducing) the annual MTCs. This is because annual MTCs for most people in this group will be substantially smaller than the compulsory 3% employer contribution to KiwiSaver which will continue to provide a substantial incentive to both join and contribute to KiwiSaver. This is supported by observations of the contributions rate after the Budget 2011 changes to KiwiSaver annual MTCs (see figure 1 above).

37. The annual MTCs however may have more of a sustained incentive effect on making contributions (at least up to contributions of $1,042.86 per annum) to KiwiSaver than the kick-start which merely encourages joining the scheme.

38. The annual MTCs also have higher marginal utility to lower income earners. Evidence suggests that lower income earners are more likely to be in the KiwiSaver target group (however the relationship is quite weak). Therefore, removing or reducing the annual MTCs may marginally reduce the (already low) target effectiveness.

Change the scope of eligibility for annual MTCs

39. As discussed above, it is very difficult to target KiwiSaver subsidies, including the annual MTCs to the target population of the policy with reference to conventional socio-economic indicators such as income. While those on higher incomes were found in Law, Meehan and Scobie (2011) to have less of a saving ‘problem’, the relationship between higher incomes and a lack of a retirement savings deficit is very weak.

40. Therefore, we have not considered policy options to change the scope of eligibility for the annual MTCs.

Retaining successful elements of KiwiSaver

41. As the KiwiSaver Evaluation highlights, the scheme has had administrative success. The enrolments in the scheme have exceeded expectations. The automatic enrolment features have also been successful in boosting and retaining participation in a savings scheme and opt-out rates are declining. Therefore changes should not compromise the administrative efficiency.

Impacts

42. The likely impacts of the proposals considered in this statement are as follows:

43. On KiwiSaver members:

a. There is likely to be a limited effect on savings behaviour if the proposed changes to the kick-start and/or annual MTC are pursued;

b. If the kick-start is reduced or removed then new enrolees in KiwiSaver will have lower KiwiSaver balances at retirement due to reduced subsidies (and returns on those amounts); and

c. If the annual MTCs are reduced or removed then KiwiSaver members will have lower KiwiSaver balances at retirement due to the reduced subsidies (and returns on those amounts).

44. On KiwiSaver providers:

a. Lower numbers of KiwiSaver members (particularly among the self-employed and children) and therefore lower revenues from fees and/or a greater number of dormant accounts (if affected individuals stop contributing); and

b. Cost of preparing revised publicity material and amended staff training requirements, particularly in the period immediately after implementation. We expect that the impacts will be low if providers can rely on normal turnover of publicity material and on Inland Revenue publicity material. The legislation to give effect to this proposal will provide relief to KiwiSaver providers for compliance with disclosure requirements.

45. On employers: there may be some impacts on information and education provided to employees about KiwiSaver, however, much of this is provided by Inland Revenue in any case.

46. On Inland Revenue:

a. Administrative costs of changing systems to remove the relevant subsidies. In the case of a removal of the kick-start, this amounts to $210,000 (including contingency). Changes to the annual MTCs will require more significant system changes and would require a 12-month lead in time and a costing is not available.

47. On other Government agencies:

a. Administrative costs of changing publicity material and guidance on KiwiSaver subsidies.

National saving, one-off enrolment and HomeStart

48. The analysis has focussed on fiscal savings from changes to KiwiSaver. We have not undertaken a comprehensive analysis of the effects of these policy changes on other policy issues which have been discussed in the context of KiwiSaver changes in the past.

49. The 2011 Budget changes to KiwiSaver removed the tax-free status of employer contributions to KiwiSaver, halved the annual member tax credit and increased the compulsory employer and employee contribution rates to 3%. A future one-off enrolment exercise was also announced, subject to a fiscal surplus. The Treasury’s advice in advance of those changes analysed the effect of policy options on national savings (and the NIIP). The current advice has not analysed those matters, however, we note that if the same logic were applied, a reduction in KiwiSaver subsidies would positively affect national savings based on available evidence.

50. The Government still intends to conduct a one-off enrolment exercise when fiscal conditions allow. This would increase membership in KiwiSaver by taking advantage of individuals’ inertia as individuals are more likely to stay put in the scheme once already enrolled (and required to actively take steps to “opt-out”). This would only have a positive effect on national saving under the condition that the increased cost from annual MTC payments (public dis-saving) did not exceed the additionality in private saving, which Law, Meehan & Scobie (2011) estimates to be one-third.

51. Individuals who are not engaged in personal financial management and thus myopic about retirement saving can also have welfare-enhancing outcomes if their decision to save is made for them by automatic enrolment. It is possible that these are the individuals most likely to passively remain in KiwiSaver following auto-enrolment. Individuals who are saving appropriately will at best not experience any improvement in welfare, while individuals who are already saving too much may have their welfare reduced.

52. Finally, the Government’s HomeStart policy allows KiwiSaver members to use the annual member tax credit payments towards a first home deposit under that scheme. We have not considered the extent to which a reduction in the generosity of the kick start and annual member tax credits will affect the future success (or otherwise) of the HomeStart policy.

Consultation

53. We have consulted with Inland Revenue in relation to the policy options and implementation of these within the constraints of Budget 2015. The Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (Consumer and Commercial Law section) were consulted. The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet was informed.

54. The consultation was necessarily limited due to the Budget sensitivity of this matter and the Ministerial prioritisation given to it.

Conclusions and recommendations

55. Removing of reducing the generosity of KiwiSaver subsidies would improve the value for money of the scheme. However, it is highly unlikely that the target effectiveness can be materially improved if the target group remains as defined by the Act.

56. The extent and scope of a reduction or removal of the KiwiSaver subsidies (i.e. whether to cease the kick-start or annual MTCs or adjust their generosity) would depend on the relative prioritisation Ministers wish to give to competing fiscal strategy concerns and Government policies.

Implementation plan

57. Amendments to the KiwiSaver Act 2006 will be required to give effect to the proposals contained herein.. Amendments will also be required to the Securities Act 1978 and Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013 (for those providers who have transitioned over to the new regime) to provide relief to KiwiSaver providers whose offer documents and investment statements may breach disclosure rules because those documents will still contain the current rules relating to investors’ entitlement to the kick-start and/or annual MTCs.

58. In order to achieve the desired fiscal savings in respect of the removal of the kick-start, it will be necessary to announce the policy change and pass the legislation at the same time. This is because fiscal savings would be undermined if individuals could enrol in the scheme in the period between announcement of the policy change and a law change.

59. Inland Revenue is confident that it can implement a complete removal of the kick-start payment effective from Budget day (and also later dates). No major administrative barriers to implementation have been identified for a complete removal of the kick-start payment. Changes are required in the IRD’s SAP computer system (which sits outside of FIRST) but not to the FIRST system. There are some implementation issues relating to processing of different types of enrolees that Inland Revenue have reported to the Minister of Revenue about and are resolving.

60. A 12-month lead-in period is required for changes to annual MTCs means that people making contributions after the changes will be aware of any reduction in generosity of subsidy.

Monitoring, evaluation and review

61. As explained above, the impetus for the consideration of current changes was the conclusion of the seven year Inland Revenue-led KiwiSaver Evaluation. That Evaluation focussed on the public policy outcomes of KiwiSaver. No further evaluation of this kind is planned for KiwiSaver and indeed may not even be possible due to limitations on availability of household savings data. Therefore, it is not expected that future evaluation of the current policy change proposal will be carried out other than standard collection of enrolment and contributions data by Inland Revenue.

62. However, it will be possible to assess the fiscal cost of the scheme by comparing enrolment and contributions data with the cost to the Government of KiwiSaver incentive payments, and judge value for money. Broadly if the ratio improves, this will indicate success, but it will not indicate whether the policy has become more targeted.

63. There are no other plans to review this proposal to change KiwiSaver policy.

1 It is likely that a similarly low proportion of people who were not members of KiwiSaver at the time of the study would be part of the programme’s target group as defined.