Chapter 7 - Miscellaneous issues

- Time of supply when consideration is unknown

- Agents acting for purchasers

- Services performed on boats and aircraft exported under their own power

- Non-resident registration rules – services received by a registered person

- Non-resident registration rules – imported goods

- Goods moved offshore by GST-registered non-residents

- Grouping limited partnerships

Time of supply when consideration is unknown

7.1 In general, the time at which a good or service is supplied is the earlier of when an invoice is issued or a payment is received. A person accounting on an invoice basis will return GST on the supply in the period where the time of supply has been triggered.

7.2 An exception to this rule is when goods are received under an agreement (other than a hire agreement), but the total consideration of the supply is not known at the time the goods are appropriated under that agreement. A timing rule (section 9(6)) splits the supply into different parts based on “the extent to which any payment under the agreement is due or received or an invoice has been issued”. Hence, the time of supply for each part is determined separately, and the supplier may return GST for each separate part.

7.3 Section 9(6) is limited in application to goods that are supplied under an agreement. The Act does not provide a similar rule for supplies of services. However, the same issue can arise in relation to supplies of services – for example, when the time of supply is triggered by the payment of a deposit, but the total consideration depends on the services performed.

7.4 In addition, the timing rule only applies when the goods are received under an agreement. However, the difficulty in accounting for GST is not confined to when the supply is received under an agreement, but could occur in any case when the time of supply has been triggered, prior to the final consideration payable being known.

7.5 An associated problem arises if the recipient of the supply requests a tax invoice. A tax invoice must be furnished within 28 days of the request, and is required to include the consideration for the supply, which may be unknown. This creates problems with the current invoicing rules, which permit the issue of only a single tax invoice in relation to a supply.

7.6 If the consideration for a supply is altered in certain ways, a debit or credit note may be issued to account for the variation. However, it is not clear that these rules apply when the consideration is not varied, but becomes known later.

Suggested solution

7.7 The section 9(6) timing rule could be extended so that it applies to any supply of goods or services where the consideration has not been determined at the time a payment is first received or an invoice issued. The supply of goods or services would be deemed to be made to the extent that payment is due or received or an invoice issued.

7.8 Splitting the supply into multiple supplies, based on payment being made or due, or an invoice being issued would more clearly enable a supplier to return GST as the consideration becomes known, and allow for invoices to be issued in respect of each of these supplies.

Agents acting for purchasers

7.9 Generally, when an agent acts on behalf of a person in making supplies of goods and services, the GST consequences will be the same as if the person performed those actions themselves.

7.10 In certain situations, a person may elect out of these rules. When an agent acts for a supplier, the parties may elect to “opt out” of the agency rules, and treat the supply as two separate supplies – between the principal and the agent, and between the agent and the recipient.

7.11 The amendment providing for this “opt out” was made in 2013 following concerns that some taxpayers’ billing systems would automatically issue a tax invoice. Where both the principal and agents’ systems did so, it could breach the rule providing for only a single tax invoice to be issued for each supply, as only one supply would in fact take place. The amendment ensured that this practice would not be in breach of that rule by effectively creating an “extra” supply.

7.12 This amendment also provided that the principal could not take a bad debt deduction for non-payment when the agent had been paid. This was to avoid a possible GST mismatch.

7.13 Officials are aware of some concerns arising when an agent is making purchases on behalf of their principal, and their billing system automatically issues a tax invoice to their principal. Currently, this would be seen as a single transaction between the principal and the supplier (who may have issued a tax invoice themselves) and the tax invoice issued by the agent may not be permitted. A purchaser and their agent cannot opt out of the agency rules and treat this as an additional supply.

7.14 However, the costs of altering systems to comply with these requirements may be high, as the systems may also need to address situations where the person is acting not as an agent, but in their own capacity, and a tax invoice may need to be issued.

7.15 Allowing for agents acting on behalf of purchasers and their principals to agree to opt out of the agency rules would reduce compliance costs in a similar way as for suppliers acting through an agent. It would also better align the GST system with what occurs in practice.

Suggested solution

7.16 An amendment could be made to include an opt-out provision for purchasers and their agents, similar to the one for suppliers and their agents. A purchaser and their agent could agree to treat a supply or type of supply as two separate supplies, being between the supplier and the agent, and the agent and principal. Using this provision would be optional – principals and their agents would not be required to treat a supply as two supplies.

7.17 Similar to the rules for suppliers’ agents, this amendment would address technical non-compliance. It would also be appropriate to limit the scope of the amendment to this purpose. As a base protection measure, the agent would be prohibited from taking a bad debt deduction for non-payment by their principal, the purchaser. Under existing rules, the agent would not be treated as making a supply, so would not receive a deduction for non-payment.

Example

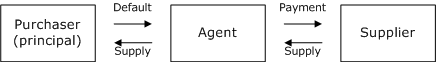

The agent pays consideration to the supplier, and invoices their principal for reimbursement. The principal defaults, and the debt goes bad. If the agent and principal have opted out of the agency rules, under the suggested amendment, this will be in respect of a taxable supply, as below:

However, previously there would not have been a taxable supply, and the agent would not be entitled to a bad debt deduction. Allowing a deduction therefore goes beyond the issue of compliance with the tax invoice rules.

7.18 The opt-out to the agency rules should only apply when the agent is New Zealand-resident. It is possible that a non-resident agent may receive supplies of services without GST applying, which are then provided to a New Zealand resident without attracting GST.

Services performed on boats and aircraft exported under their own power

7.19 GST is not intended to be a tax on consumption that occurs outside New Zealand. Consequently, a variety of supplies of goods that are exported can be zero-rated, including the supply of a boat or aircraft that is to be exported under its own power by the recipient (although export must generally occur within 60 days of the purchaser receiving possession).

7.20 In addition, certain goods and services supplied in relation to goods that are to be exported can be zero-rated. This includes services supplied in relation to goods that have been entered for export by the supplier, and also certain goods and services provided in relation to temporary imports. For example, goods that are affixed to a temporarily imported boat in the course of repairs may be zero-rated.

7.21 Goods and services supplied in relation to a boat or aircraft purchased in New Zealand, which is to be exported under its own power, cannot however currently be zero-rated.

Example

Thomas purchases a yacht from a GST-registered shipwright in New Zealand, which he will sail out of New Zealand within 60 days.

Before sailing the yacht away from New Zealand, he arranges to have the yacht repainted, and for new railings to be installed around the sides.

The shipwright can zero-rate the supply of the yacht, as it is exported under its own power within the prescribed timeframe.

The supply of the railing and the repainting cannot be zero-rated.

7.22 The inability to zero-rate goods attached to, or services provided directly in connection to, newly purchased boats or aircraft which will be exported, seems anomalous. The consumption of these goods and services is unlikely to occur in New Zealand, and their supply should be zero-rated.

7.23 A newly purchased boat or aircraft that is to be exported under its own power must generally be exported within 60 days to qualify for zero-rating. This time period may be extended when certain circumstances beyond the control of the supplier and recipient prevent export within the time period.

Suggested solution

7.24 An amendment could be made to ensure that these services and goods supplied in connection to boats or aircraft exported under their own power within 60 days of sale (as a zero-rated supply) are zero-rated. The circumstances when an extension to the 60-day time limit is available should be expanded to include when export cannot occur within this time period, due to this work being performed on the boat or aircraft.

Non-resident registration rules – services received by a registered person

7.25 On 1 April 2014, rules in section 54B took effect that allow non-resident businesses to register for New Zealand GST in order to claim input deductions for certain business expenditure. The rules allow non-residents to register, where they satisfy certain criteria.

7.26 A legislative mismatch has inadvertently been created between section 54B(1)(c) and section 11A(2)(b).

7.27 Section 11A(2)(b) provides that a New Zealand supplier cannot zero-rate a supply to a non-resident if “it is reasonably foreseeable, at the time the agreement is entered into, that [the ultimate recipient] will not receive the performance of the services in the course of making taxable or exempt supplies” [emphasis added].

7.28 The purpose of section 11A(2) is to ensure that, for example, the New Zealand provider of education services cannot zero-rate supplies made to a non-resident company when it is clear that the non-resident will in turn on-sell those services to an individual in their own jurisdiction. This ensures that private consumption of services in New Zealand continues to be appropriately taxed.

7.29 The effect of section 11A(2) could be undermined if the non-resident company in the example was able to register for GST in New Zealand and claim input deductions on the supply, but did not return output tax on the on-supply to the unregistered person. (In theory, the non-resident is required to be registered and return output tax on the on-supply of the services to the ultimate consumer, but it is recognised that there are practical difficulties in enforcing tax liabilities on non-residents in these situations. As a result, the tax payable on the supply subject to section 11A(2) acts as a proxy for final consumption).

7.30 Section 54B(1)(c) prevents this registration. It provides that a non-resident cannot register if their taxable activity involves “a performance of services in relation to which it is reasonably foreseeable that the performance of the services will be received in New Zealand by a person who is not a registered person”. Because section 54B(1)(c) refers only to a person who is not a registered person it does not deal with supplies received by a sole trader in New Zealand, and enjoyed by that person in their individual capacity. The services, although received by “a registered person”, will not be received in the course of making taxable or exempt supplies – they will be privately consumed.

7.31 A non-resident making supplies to such a person would be arguably entitled to register under section 54B. However, this result is contrary to the policy intent behind section 54B, because the services in question are, in essence, received outside the scope of the recipient’s taxable activity.

Suggested solution

7.32 In section 54B(1)(c) “not a registered person” ought to be replaced by “a person that does not receive the performance of the services in the course of making taxable or exempt supplies”.

Non-resident registration rules – imported goods

7.33 The base maintenance provisions in sections 20(3LB) and (3LC) broadly cover the following scenario:

- A non-resident registers for GST under section 54B.

- The non-resident then sells a high-value good to a New Zealand recipient who is not GST-registered.

- The time of supply is triggered while the good is still offshore, so no GST is payable.

- The supplier, as part of the agreement, acts as importer of the goods and pays the import GST levied under section 12.

- The supplier, as a registered person, then claims this import GST as a deduction and gets it refunded.

- The goods are delivered to the ultimate New Zealand customer without a further imposition of GST.

7.34 Without the base maintenance provisions, the net result of this transaction is that there is no GST paid for a good that is consumed in New Zealand by an unregistered person. The base maintenance provisions negate this result by deeming the recipient of the goods to have paid the import GST rather than the registered non-resident. If the recipient is GST-registered, they can claim a deduction for the import GST. If the recipient is not registered, no refund is available and the GST would be payable.

7.35 The base maintenance provisions only apply when the non-resident supplier is registered under section 54B. To qualify to be registered under that section, the non-resident must anticipate claiming input deductions of greater than $500 in its first return.[17] If the non-resident’s only connection with New Zealand is as an importer, they may not satisfy the $500 test.

7.36 The legislation therefore currently creates a potential circularity. In the scenario described above, because the importer cannot register, the base maintenance provisions do not apply. Therefore, if the New Zealand customer is GST registered:

- the customer could not claim the input deduction on the non-registered supplier’s/importer’s behalf; and

- the unregistered non-resident supplier is liable for the import GST, which it cannot recover or on-charge.

7.37 The net result is a GST impost on a business-to-business transaction. It is recognised that this may be an undesirable policy outcome.

7.38 There are some practical solutions to this issue. The right policy outcome would be achieved if the original transaction were subject to GST. This could be contractually arranged by the parties by ensuring that the goods were in New Zealand at the time of supply. Alternatively, the recipient customer could be treated as the importer of the goods. In either case, assuming the customer was registered, it could claim the GST.

7.39 In this respect, we note that the imposition of this GST cost would have been there before the introduction of the non-resident registration rules. So, in effect, the new rules do not appear to be making anyone worse off.

7.40 Therefore, there is a question whether legislative change is necessary given that parties presumably have the option of returning to a previous practice that achieved a neutral outcome. However, the counter-argument, is that the legislation should provide a remedy for supply chains that are using a system whereby a GST cost is borne by businesses.

Suggested solution

7.41 On balance, we consider a legislative amendment should be made. This could best be achieved by eliminating the section 54B(1)(b) requirement for a $500 input tax deduction if the person’s liability to pay GST is limited to GST paid under section 12. This would allow non-residents that operate only as importers the ability to register under section 54B. This in turn would allow the base maintenance provisions to work as intended and push the GST liability onto the New Zealand customer.

Goods moved offshore by GST-registered non-residents

7.42 A registered person who incurs GST on goods paid to the NZ Customs Service on importation and purchased to make taxable supplies may deduct this GST to the extent that the goods or services are used to make taxable supplies.

7.43 One requirement of a taxable supply is that it is made in New Zealand. Supplies will be made in New Zealand when the supplier is a resident of New Zealand, but not when the supplier is a non-resident unless the goods supplied are in New Zealand at the time of supply, or the services supplied are physically performed in New Zealand by a person who is in New Zealand at the time the services are performed.

7.44 An issue arises when a GST-registered person, who is only a resident to the extent they carry on activities in New Zealand, takes a deduction for GST charged on goods in New Zealand, and subsequently exports those goods while retaining ownership.

7.45 When these goods are subsequently exported, they will no longer be used to make taxable supplies, as supplies made by non-residents are generally deemed to be made outside New Zealand, with certain exceptions.

7.46 A consequence of this is that the apportionment and adjustment rules will require the person to repay some or all of the GST they deducted when they purchased those goods. This effectively taxes goods ultimately consumed outside New Zealand by the claw-back of deductions.

Example

Virginia is an Australian singer, who comes to New Zealand on tour. She plans to sell merchandise at her concerts and is GST-registered.

When she imports the merchandise, she pays GST to NZ Customs and claims a deduction for the GST in her GST return.

At the end of the tour, any unsold merchandise is exported to the next destination of the tour, and sold there. As she is a non-resident and supplying goods outside New Zealand, she is no longer using the merchandise to make taxable supplies. She must therefore adjust the input tax deduction claimed.

7.47 This issue is restricted to non-residents. The Act deems goods supplied by a New Zealand resident as being supplied in New Zealand and the zero-rating rules ensure that this does not result in GST being charged on supplies of goods and services which are consumed outside New Zealand. This means a New Zealand resident may retain any GST deducted on those exported goods.

7.48 This issue is also further restricted to non-residents who are not registered under the special non-resident registration rule (section 54B). Non-residents registered under this rule may deduct GST charged on goods or services, when they are used to make supplies outside New Zealand, which would be taxable supplies if made and received in New Zealand.

7.49 This result seems inconsistent with the purpose of GST, as it results in GST effectively being imposed on consumption outside New Zealand, through the denial of deductions.

7.50 It also results in a different GST outcome for the affected group compared with residents and non-residents registered under the non-resident registration rule, who may generally deduct GST incurred on goods used for business purposes, regardless of where they are used.

7.51 This is a relatively new issue. Prior to the application of the current apportionment rules, from April 2011, the non-taxable use of these goods would be taxed through a deemed supply, which was zero-rated in this situation. Consequently, the problem would not have arisen.

Suggested solution

7.52 Officials consider that where a non-resident, registered under the ordinary registration rules, acquires goods and applies them to make supplies through their overseas business activities, they should be able to treat those supplies as being made and received in New Zealand.

Grouping limited partnerships

7.53 Currently, limited partnerships are specifically included within the “company” definition in section 2 of the Act. This change was made by the Limited Partnerships Act 2008. As a result, limited partnerships are treated differently to general partnerships, which are GST entities by virtue of the “person” definition including an “unincorporated body of persons”.

7.54 Given there are relatively few provisions in the Act that apply specifically to “companies”, it is rare that this distinction actually means that limited partnerships are treated differently to general partnerships. However, one area where this distinction results in a difference in treatment is the grouping provisions (section 55).

7.55 Under section 55(1), a company is generally only eligible to group with other companies if they are part of a “group of companies” for the purposes of section IC 3 of the Income Tax Act. A limited partnership is not usually a “company” for income tax purposes, so there is a question as to whether an limited partnership could take advantage of section 55. There is an interpretative argument that these provisions can only be read sensibly if “company” in this context takes on its GST Act definition, but this is not clear.

7.56 There is a general grouping provision that applies to allow other entities to form a GST group if two or more registered persons exercise sufficient control over a collection of entities (section 55(8)). This is achieved by application to the Commissioner and allows collections of, for example, trusts to register as a group. However, section 55(8) specifically excludes “companies” from its ambit – on the assumption that companies will be eligible to group under section 55(1).

7.57 This combination of provisions leaves the possibility that limited partnerships may be the only entity that cannot group for GST purposes. We do not consider there is a policy justification for singling out limited partnerships in this way. The question is whether section 55(1) or section 55(8) should be amended to address this.

7.58 There is a potential difficulty in assuming that limited partner rights will always equal appropriate “voting interests”, as required to group under the section 55(1) test. In contrast, grouping under section 55(8) is governed by a control test, where entities that are controlled by each other, or the same person or partnership, may form a GST group, and this may be more easily applied in the limited partnership situation.

Suggested solution

7.59 We suggest that limited partnerships be able to group under section 55(8).