Appendix - Reprint of Question We’ve Been Asked QB 15/01

Income tax: tax avoidance and debt capitalisation

All legislative references are to the Income Tax Act 2007 unless otherwise stated.

This Question We’ve Been Asked is about s BG 1.

Introduction

1. At a tax conference held in November 2013 there was a discussion of whether s BG 1 would apply to certain scenarios. This Question We’ve Been Asked (QWBA) considers one of those scenarios concerning debt capitalisation. Three other scenarios were the subject of an earlier QWBA: QB 14/11 Income Tax – scenarios on tax avoidance, published in October 2014.

2. In the scenario, the arrangement and the conclusion reached are framed broadly. The objective is to consider the application of the general anti avoidance provision of s BG 1. Accordingly, the analysis of the scenario proceeds on the basis that the tax effects under the specific provisions of the Act are achieved as stated. Also, the specific anti avoidance provision of s GB 21 is not considered. However, it should not be presumed that this would always be the case. Also, except where shown below, additional relevant facts or variations to the stated facts might materially affect how the arrangement operates and a different outcome under s BG 1 might arise. Accordingly, the Commissioner’s view as to whether s BG 1 applies must be understood in these terms.

3. Section BG 1 is only considered after determining whether other provisions of the Act apply or do not apply. Where it applies, s BG 1 voids a tax avoidance arrangement. Voiding an arrangement may or may not appropriately counteract the tax advantages arising under the arrangement. If not, the Commissioner is required to apply s GA 1 to ensure this outcome is achieved.

4. For a more comprehensive outline of the Commissioner’s position on the law concerning tax avoidance in New Zealand, reference should be made to the Commissioner’s Interpretation Statement: IS 13/01 Tax avoidance and the interpretation of sections BG 1 and GA 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007 (July 2013).

Question

5. Whether s BG 1 applies in the following circumstances:

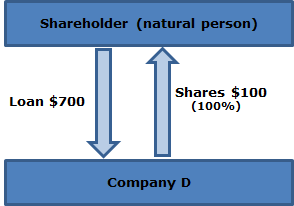

- A New Zealand resident individual is the sole shareholder of Company D.

- Company D is a qualifying company in the following financial position:

| Cash | 200 |

| Total Assets | $200 |

| Shareholder loan | 700* |

| Share capital | 100 |

| Accumulated deficit | (600) |

| Total Equity and Liabilities | $200 |

* The shareholder loan is a “financial arrangement” for the purposes of the financial arrangements rules (FA rules) of subpart EW of the Act and is not part of a wider financial arrangement.

6. Under an arrangement the shareholder and Company D agree that:

- Company D will issue additional shares;

- the shareholder will subscribe $500 for the shares;

- the shareholder’s indebtedness to Company D for the share subscription of $500 will be offset against the shareholder loan; and

- the company will repay the $200 balance of the loan in cash.

Answer

7. The Commissioner’s view is that s BG 1 would potentially apply to this arrangement.

Explanation

8. The apparent objective of this arrangement is to eliminate the loan owed by Company D to its shareholder in circumstances where Company D issues further shares to that shareholder.

Tax effects

9. The tax effect of the loan ending is that s EW 29(3) requires Company D and the shareholder to each perform a base price adjustment (BPA) under s EW 31 in the income year the loan is eliminated.

10. The BPA is calculated using the formula in s EW 31(5):

consideration — income + expenditure + amount remitted

11. In this scenario, it can be assumed that the income and expenditure items in the BPA formula are zero. The amount remitted item will also be zero for Company D as it is the borrower and unable to remit the debt. The relevant item in the BPA formula for present purposes is “consideration”.

12. “Consideration” is relevantly defined as—

... all consideration that has been paid, and all consideration that is or will be payable to the person for or under the financial arrangement, minus all consideration that has been paid, and all consideration that is or will be payable, by the person for or under the financial arrangement.

13. The consideration paid to Company D is the original amount of the loan of $700. The consideration paid by Company D is the sum of the $200 paid in cash and the $500 offset against the loan balance. Therefore, Company D’s BPA calculation is:

($700 – ($200 + $500)) – $0 + $0 + $0 = $0.

14. The tax effect of the arrangement for Company D is that no income or deduction will arise under the BPA as the calculation returns neither a positive nor a negative figure.

15. Similarly, the tax effect for the shareholder is that there is no income or deduction arising under the BPA as the shareholder’s BPA calculation is:

(($200 + $500) – $700) – $0 + $0 + $0 = $0.

Parliament’s purposes

16. Parliament’s purposes for the FA rules is to require income and expenditure under financial arrangements to be recognised by the parties on an accrued basis over the term of the arrangement and to require them to disregard any distinction between capital and revenue amounts. The FA rules provide the tax outcomes for each of the parties to a financial arrangement. In this scenario, this will be the shareholder and Company D.

17. The Court of Appeal in Alesco New Zealand Ltd v CIR [2013] NZCA 40 also noted that the financial arrangements rules recognise the economic effect of a transaction. The court stated as follows:

[71] In our judgment, the financial arrangements rules were intended to give effect to the reality of income and expenditure – that is, real economic benefits and costs. They were designed to recognise the economic effect of a transaction, not its legal or accounting form or treatment. The question is whether the taxpayer has “truly incurred the cost as intended by Parliament”. [Emphasis added]

18. One issue that arises is whether the parties to a financial arrangement are looked at in combination as a single economic unit. The Commissioner considers that reaching a view on this issue must be derived from the provision in question. While the FA rules are concerned with the overall economic effects of a transaction, in the Commissioner’s view, this requires looking at each of the parties involved in isolation. Aside from company consolidation and amalgamation rules, there is no indication Parliament contemplated that the parties should be considered from the perspective of a single economic unit when it comes to the BPA. This conclusion regarding Parliament’s purpose for the FA rules does not mean that where other provisions of the Act are in question Parliament may have contemplated a single economic unit perspective was appropriate.

19. Parliament’s specific purpose for the BPA is for it to apply as a “wash up” mechanism which operates when a financial arrangement matures or is disposed of. It operates to account for any gains or losses that have not already been treated as income and expenditure during the life of the financial arrangement. The BPA ensures that for each financial arrangement, all income is returned and all expenditure is deducted.

20. One situation where the BPA applies as a “wash up” mechanism relevant to this scenario is where ultimately a financial arrangement is not repaid in full. In that case, the BPA formula item “consideration” will be positive for a borrower on account of the consideration received by them being greater that the consideration paid by them. Leaving aside any effect of the other items in the formula (income, expenditure and amount remitted), this would lead to a positive BPA figure. Under s EW 31(3) a positive BPA is income to the borrower (often referred to where there is a debt remission as “remission income”). In the present scenario, had the shareholder of Company D forgiven $500 of the loan instead of subscribing for additional shares, Company D would have had remission income of $500 calculated under the BPA as follows:

($700 – $200) – $0 + $0 + $0 = $500.

21. As a qualifying company, if Company D did not pay the tax on the remission income, the shareholder would have to meet the liability on account of the company (although nothing turns on the company being a qualifying company in terms of the application of s BG 1).

Facts, features or attributes

22. For the FA rules, a fact, feature or attribute Parliament would have expected to see present in an arrangement bringing a financial arrangement to an end is that there has been a discharge in economic terms of the obligations of each of the parties under the arrangement. That is, the borrower has borne the economic cost of repaying the loan and the lender has received an economic benefit.

23. This means that, on the maturity of a financial arrangement Parliament would expect that the consideration paid or payable by a person actually equalled the consideration received or receivable by another person in an economic sense.

24. Where this does not occur, Parliament therefore intended that income will arise for a borrower where an obligation under a financial arrangement, including principal, is forgiven or otherwise unpaid. This is intended to reflect that the borrower has made an economic gain, or has economically had an increase in wealth, by virtue of not having to repay an amount which they would otherwise be required to pay.

Extrinsic material

25. This view is supported by extrinsic materials including the Final Report of the Consultative Committee on the Taxation of Income from Capital (The Valabh Committee, October 1992). The committee proposed that debts remitted should be deemed to be repaid in full so that no remission income should arise. However, this proposal was rejected by the Government. In the foreword to that report, the Ministers of Finance and Revenue stated that this proposal was “inconsistent with [Government’s] revenue strategy” (at [16]).

26. In a subsequent discussion document, The Taxation of Financial Arrangements: A Discussion Document on Proposed Changes to the Accrual Rules, December 1997 (the discussion document), the asymmetrical tax results arising from retaining the debt remission and bad debt rules were stated to be “an inevitable consequence of maintaining a capital revenue boundary” (at [11.5]). The discussion document also referred to provisions that ignore remission income in the context of consolidated groups as a “substantial concession to the general rule” (at [11.32]).

Commercial and economic reality of the arrangement

27. Next it is necessary to analyse the commercial and economic reality of the arrangement to see whether the facts, features or attributes Parliament would expect to be present (or absent) to give effect to its purpose are present. In the present scenario this requires ensuring Company D has in reality discharged its obligations under the loan when viewed in a commercially and economically realistic way. If so, the tax effects of the arrangement will be within Parliament’s contemplation for the FA rules.

28. Company D has discharged its obligations under the loan to the extent of the $200 cash it has paid to the shareholder and this amount is correctly treated as an item of consideration paid in its BPA calculation. Also, on the face of it, it is accepted that consideration for BPA purposes need not be cash but can be money’s worth, such as where mutual obligations have been offset. This has occurred in this arrangement to the extent of the $500 share subscription. A financial arrangement is defined in s EW 3(2) in terms of an arrangement involving “money” being provided or received as consideration. The definition of “money” in s YA 1 specifically includes money’s worth, whether or not convertible into money, and s EW 31 includes within the BPA calculation all consideration paid to or by the person.

29. However, a s BG 1 enquiry is not limited to the legal form of the arrangement. The whole of the arrangement is examined to establish its commercial and economic reality. Given the section at issue, the avoidance inquiry examines whether the loan is in reality repaid, as Parliament would expect where there is no remission income. Therefore, the arrangement is examined to see whether Company D repays the loan in a commercially and economically real sense, and whether the shareholder is repaid in a commercially and economically real sense.

30. In the scenario, there is no actual or economic cost to Company D in issuing shares to the existing shareholder. It has not suffered the full economic cost of repaying the loan. The shareholder, in turn, has not received an economic benefit. There is no change to the shareholder’s interest in the company so the shareholder will not receive a “gain” in value from the receipt of the shares commensurate with the face value ascribed to them by the parties. Company D will simply have more shares on issue, and, the existing shareholder will hold more shares in a company in which they already owned all of the shares. The shareholder effectively finances the repayment of $500 of the loan themselves. There is an element of artificiality and contrivance in this aspect of the arrangement.

31. Accordingly, the parties have not given or received full repayment of the loan when viewed in commercial and economic terms. In commercial and economic reality, the effect of the arrangement is that from Company D’s perspective it discharges its obligations under the loan thereby eliminating a liability for $700 without it suffering any economic loss or expending money or money’s worth beyond the $200 paid. This conclusion does not turn on the fact that Company D is insolvent.

32. When looking at the financial consequences of the arrangement it should be borne in mind that the relevant provision at issue is s EW 31 and the BPA outcome arising for Company D. Parliament’s relevant purpose is concerned with a single taxpayer and whether that taxpayer has remission income. As stated at paragraph 18, except for consolidated groups, there is no relevant Parliamentary purpose that provides for the parties to the financial arrangement to be looked at as if they were a single economic unit when determining if remission income has arisen. The FA rules apply to individual taxpayers. When viewed in a commercially and economically realistic way the conclusion is that the loan has, in reality, been remitted by the shareholder to the extent of $500.

33. The Commissioner also considers the commercial and economic reality of the arrangement would be the same even if the shareholder had subscribed for the shares in cash for $500 and Company D had fully repaid the loan in cash.

Applying the Parliamentary contemplation test

34. Accordingly, it is the Commissioner’s view that the arrangement does not appear to exhibit the necessary facts, features or attributes that Parliament would have expected to see present to give effect to its purposes for the FA rules and the BPA in particular. Again, in the Commissioner’s view, this means the arrangement could be outside Parliament’s purposes for the FA rules as it circumvents remission income arising under the BPA. While the Commissioner accepts that arguments could be made to the contrary, on balance, it is considered that the arrangement has tax avoidance as a purpose or effect.

35. It has been suggested that the above conclusion is inconsistent with the view of the High Court in AMP Life Ltd v CIR (2000) 19 NZTC 15,940 (HC), where McGechan J commented (at [129]) that a debt capitalisation on its own would not be a tax avoidance arrangement. However, in the Commissioner’s view, his Honour’s comment does not necessarily reflect a considered judicial view on the issue of debt capitalisation in the context of tax avoidance. The BPA and debt remission income were not at issue in the case, and McGechan J was responding to the arguments before him concerning whether there was actually an “arrangement”. The Commissioner also notes that the case was heard and decided prior to the Parliamentary contemplation test being set out authoritatively by the Supreme Court in Ben Nevis Forestry Ventures v CIR [2008] NZSC 115. There is no indication that when making his comments concerning debt capitalisation at [129] McGechan J was directly considering what Parliament contemplated for the FA rules in the present context.

Merely Incidental test

36. The next step is to test whether the tax avoidance purpose or effect of the arrangement is merely incidental to a non-tax avoidance purpose or effect. If so, s BG 1 will not apply to the arrangement, even though the arrangement has a tax avoidance purpose or effect. A “merely incidental” tax avoidance purpose or effect is something which follows from or is necessarily and concomitantly linked to, without contrivance, some other purpose or effect.

37. Sometimes, quite general purposes are put forward to explain arrangements, and there is a question how to treat such purposes in the context of the merely incidental test. General purposes that can potentially be achieved in several different ways will not explain the particular structure of the arrangement. Section BG 1, including the merely incidental test, is applied to the specific arrangement entered into. In the present context, the elimination of the shareholder loan or the alleviation of the company’s insolvency would be insufficient to explain the particular arrangement and to establish that the tax avoidance purpose or effect is merely incidental to these purposes or effects. This is the situation given the limited facts of the arrangement in this scenario. The tax avoidance purpose or effect appears to be either the sole or the main purpose or effect of the arrangement. Accordingly, the tax avoidance purpose or effect is unlikely to be merely incidental to another purpose or effect of the arrangement and the arrangement in the scenario fails the merely incidental test.

38. However, the Commissioner accepts that in a particular case it may be possible for any tax avoidance purpose or effect of an arrangement involving debt capitalisation to be merely incidental to some non tax avoidance purpose or effect. If so, s BG 1 would not apply. For this to be the case, the non tax avoidance purposes or effects would need to explain the involvement of a debt capitalisation within the particular structure of the arrangement. An example may be where a regulatory body imposes a certain approach to the restoration of solvency to a subsidiary.

Reconstruction

39. If s BG 1 is to apply to give rise to remission income for Company D, it might be thought that there should be a corresponding deduction for the shareholder as part of a reconstruction under s GA 1. However, Parliament has made a deliberate choice for the FA rules that sometimes it will produce an asymmetrical result. An asymmetrical result can arise where the lender is not entitled to a deduction. For instance, had the shareholder in this scenario remitted the $500, the shareholder would not have a negative BPA (a negative BPA is a deduction under s EW 31(4)). This is because the BPA formula item “amount remitted” would include any amount not included in the item “consideration” on account of the amount being remitted by the shareholder. This would give a BPA calculation of:

($200 – $700) – $0 + $0 + $500 = $0.

40. For the shareholder to obtain a deduction for remitting the financial arrangement they would need to satisfy the bad debt rules in s DB 31. Relevant to the present scenario, if the parties are associated (as they are here) no bad debt deduction is permitted (s DB 31(3)). To be consistent with this, it would follow that any application of s BG 1 in this scenario would not result in the shareholder being provided with a $500 deduction as a consequential adjustment under s GA 1.

Factual variations

41. This arrangement can be contrasted with the situation where there is an issue of shares to a third party by a solvent company. In that case, it is more likely that the shares issued as consideration will have an economic effect. The existing shareholders of a company would suffer a dilution of their investment. The third party would obtain an equity interest in the company and there may be a change in the effective ownership of the company. This type of situation is more likely to have been contemplated by Parliament as one where no remission income arises under the BPA (although this would need to be considered on a case by case basis).

42. Given the above, it might be asked whether the fact that the company is solvent is relevant in the third party lender situation. The question is answered by considering what facts, features and attributes Parliament would expect to see present. Parliament would expect that a lender receives repayment in a commercially and economically real way. In some situations, depending on the facts, shares in an insolvent company may have some value to a third party lender. Examples could be where there is the prospect of the company regaining solvency or it has some valuable assets. In most other situations, shares in an insolvent company will not have any value to a third party lender and so will not constitute repayment of a loan in a real sense.

References

Subject references:

Base price adjustment

Consideration

Debt capitalisation

Debt remission

Financial arrangement

Merely incidental

Tax avoidance

Tax avoidance arrangement

Legislative references

Income Tax Act 2007: ss BG 1, EW 3, EW 29, EW 31, GA 1, s YA 1 definition of “money”

Case references

AMP Life v CIR (2000) 19 NZTC 15,940 (HC)

Alesco New Zealand Ltd v CIR [2013] NZCA 40

Ben Nevis Forestry Ventures Ltd v CIR [2008] NZSC 115

Related rulings/statements

IS 13/01 Tax avoidance and the interpretation of sections BG 1 and GA 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007 (July 2013)

Other references:

Final Report of the Consultative Committee on the Taxation of Income from Capital (The Valabh Committee, October 1992)

The Taxation of Financial Arrangements: A Discussion Document on Proposed Changes to the Accrual Rules, (December 1997)