Chapter 3 - LTC entry criteria

Introduction

3.1 A set of entry criteria apply to limit the type of entity that can be a LTC and to limit the type and number of owners. Given that flow-through treatment includes the flow-through of losses, the entry criteria also help to limit the opportunity for those losses to be traded or otherwise utilised by those not incurring the economic loss.

3.2 A key consideration of the review has been whether these entry criteria sufficiently match the intent of the LTC regime as designed for closely controlled companies.

Current entry criteria

3.3 We have reviewed the entry criteria against the “target audience” for the LTC regime, namely, investments that could otherwise be made by an individual or small group of individuals, including through a family trust. Other tax-transparent options are available for more widely held investments and, given their different target audience, we do not see the availability of such options as a reason for widening the eligibility criteria for LTCs.

3.4 For example, given that more widely held vehicles such as limited partnerships open up the possibility for loss retailing,[15] it is appropriate that the tax legislation applies a deduction limitation rule in their case to limit the pass through of deductions to the amounts that owners have at risk. In contrast, this issues paper is recommending (see the next chapter for more detail) that the pass-through of deductions be retained for LTCs and that a deduction limitation rule should not be applied to most LTCs. In these circumstances, it is even more important that widely held investments cannot access LTC treatment.

3.5 Table 3 summarises the current entry criteria for LTCs and QCs. The QC rules are used only as a point of comparison. We are not proposing changing the current eligibility rules for QCs, which is consistent with the grandparenting of those entities.

3.6 In comparison, as noted in Table 1, the tax rules for a partnership contain no comparable entry criteria, and a limited partnership’s main entry restrictions are that it has to have at least one general partner and a limited partner. General partners manage the business and are liable for the debts and obligations of the partnership, whereas limited partners are usually passive investors and are only liable to the extent of their capital contribution. This distinction is akin to directors and shareholders in a company.

Review of company requirements

“Company” and tax resident status requirements

3.7 The LTC rules are designed to allow flow-through tax treatment to businesses that have a genuine reason for choosing limited liability corporate structures as an alternative to undertaking their activities as sole traders or as small partnerships. The requirement that the business be a “company” is, therefore, an integral part of the rules.

3.8 Likewise, given that effective look-through treatment is targeted at closely controlled New Zealand businesses, the requirement that the company be New Zealand tax resident is also appropriate.

One class of share

3.9 Currently a LTC can only have one class of share. This restriction is an important part of look-through treatment as it makes for ease of calculating relative shareholdings, which provides the basis for allocating a LTC’s income and losses. Shareholding is likely to represent a person’s contribution to a family business or a conscious decision on the part of those with interests in a company to divide the profits of a business in particular proportions. Investors in a LTC can achieve different risk profiles through the use of debt and equity, as appropriate.

3.10 We acknowledge that there can be legitimate commercial/generational planning reasons for shares to carry different voting rights and that the current restriction may inhibit some companies from becoming LTCs. A parent, for example, because of their industry expertise, may want to retain control of the decision-making process when children are introduced into the business.

3.11 In these circumstances, we consider that the “one class of share” requirement may be unnecessarily rigid. However, we remain concerned about types of shares that could produce income or deduction streaming opportunities.

3.12 As a result, we are recommending that different classes of shares carrying different voting rights be allowed, provided all other rights are the same. In particular, the shares must carry the same rights to income and losses, including on liquidation.

Foreign income and non-resident ownership

3.13 These aspects are discussed separately in Chapter 4.

Review of shareholder requirements

Maximum of five look-through counted owners

3.14 The purpose of the requirement that a LTC must have five or fewer “look-through counted owners” is to ensure that the company should be “closely controlled” by individuals. This is consistent with the idea that LTCs are a substitute for direct investment. Under the current rules:

- owners that are “relatives” are counted together;

- LTCs that own shares in other LTCs are effectively ignored, with the owners of the parent LTC being instead counted for the purposes of the five-person test;

- ordinary companies cannot directly hold shares in a LTC, but can indirectly have an interest in a LTC through receiving beneficiary income from a trust that owns shares in a LTC (a shareholding trust). In the latter case, the ordinary company’s shareholders (and those that hold market value interests) are counted as look-through owners when they have received beneficiary income in either the current year or one of the last three years;

- similarly, natural person beneficiaries of a shareholding trust are only counted if they have received beneficiary income in the current year or one of the last three years; and

- a trustee of a shareholding trust is treated as a counted owner if it has not distributed, as beneficiary income, all income attributed from the LTC interest in the current and last three years.

Relatives

3.15 To be a “relative”, a person must meet the general “associated persons” test in the tax legislation. Generally speaking, two people are related if they are:

- within the second degree of blood relationship with each other;

- in a marriage, civil union or de facto relationship with each other;

- in a marriage, civil union or de facto relationship with a person within the second degree of blood relationship;

- an adopted child of a person and persons within the first degree of relationship of that person;

- a trustee of a trust under which a relative has benefitted or is eligible to benefit.

3.16 The LTC rules also provide that dissolution of marriage, civil unions or relationships are to be ignored.

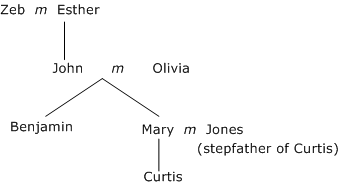

3.17 This current test can mean that significant family groups are counted together as a single LTC owner. In the following example[16] (where there is a maximum of two children per couple), if all the people mentioned owned shares in the same LTC they would be counted as one person:

3.18 The current rules, therefore, contemplate situations when up to conceivably five multi-generational families could all be shareholders in a company and that company would still be eligible for LTC status. By contrast, the QC rules, which only allow one degree of relationship, are in theory more restrictive. In practice, however, there is no evidence that this difference is leading to significantly wider overall shareholdings. Most LTCs have only one or two shareholders/owners.[17] The current test also has the benefit of being well understood given it is based on the definition of “associated person”.

3.19 Consequently, we are not proposing any changes in this area. Individuals would, therefore, continue to be treated as they are now, in other words a two degree of relationship test would continue to apply.

Companies

3.20 At present the only corporate that is permitted to have a direct shareholding in a LTC is another LTC (other than corporate trustees, which are discussed below). We are not recommending any changes in this area. The prohibition on ordinary companies owning LTC shares appears consistent with the idea that LTCs should not be widely held or used as a way to shelter company income from tax,[18] and should be retained.

Trusts

3.21 Our starting proposition in looking at trustees as shareholders of LTCs is that the entry criteria tests would have failed if the interposing of a shareholding trust allows for more owners than would have been allowed if those people had held shares directly. In saying this, it is more challenging to determine who has “benefitted” from a LTC in a trust situation. We accept it is difficult to argue that all beneficiaries will always benefit from the fact that trustees own a LTC.

3.22 Nevertheless, we are proposing changes to how trusts are measured as “look-through counted owners” because the current rules seem to be too generous in two key respects.

3.23 The first issue is in relation to the measurement period. The current test that casts back just three preceding years when considering whether a beneficiary of a trust should be counted as a look-through counted owner potentially provides scope for beneficiaries to be ‘rotated’. The rotation of beneficiaries enables the profits of the company to be distributed to a larger beneficiary class while still meeting the requirement of a maximum of five look-through counted owners.

3.24 The second issue is the focus just on distributions of beneficiary income from LTC interests. The focus on beneficiary income is a proxy for receiving a benefit. However, there are instances when a person does not receive beneficiary income, but nevertheless benefits from a trust owning LTC shares. A person might, for example, receive a distribution of trustee income. It is not difficult to envisage situations when multiple beneficiaries could receive distributions of trustee income such that the numbers could be skewed.

Example

Distributions of income from a LTC interest are made by Family Trust to 10 beneficiaries. The trustee is deciding on whether the trust’s current year income should be made as trustee income or beneficiary income. Depending on the decision, the outcome in terms of the number of look-through counted owners can vary from 1 to 11.

3.25 Furthermore, the focus on income derived just from a LTC interest may cause practical difficulties given the fungibility of money and the potential for streaming distributions to selected beneficiaries.

3.26 We note that a more restrictive test applies to QCs – in their case a trustee must distribute all dividends from the QC as beneficiary income (other than non-cash dividends). Furthermore, all beneficiaries that have derived beneficiary income from dividends since the 1991–92 income year, when QCs were introduced, are treated as counted shareholders. This reference back to 1991–92 has proved to be a compliance problem in some instances, as time has elapsed.

The proposal

3.27 We are not suggesting adopting the QC approach but rather to count all distributions made, whether beneficiary or trustee income, corpus or capital. In terms of the time period, a LTC test that tied in with other more general record-keeping period requirements would appear to be justifiable. The proposal is that a beneficiary that has received any distribution from the shareholding trust in the last six years would be a counted owner.

3.28 This six year measurement period acknowledges that any extended period would need to be enforceable in practice and that imposing stricter than usual record-keeping requirements on trustees of relatively unsophisticated trusts would be difficult to justify. Rather than tying the LTC requirement to the record-keeping period required for tax purposes, it seems more appropriate to match the time period with that generally applying to claims under the Limitations Act 2010 as trustees are required to keep records for at least that time in case a beneficiary challenges a distribution decision.[19]

3.29 Some entities are likely to lose their LTC status as a result of this proposal. This is an appropriate outcome as it ensures that the LTC ownership rules in relation to trusts do not allow more look-through owners than would be the case under direct ownership.

When there are no distributions

3.30 Currently, in the event that not all income from an interest in a LTC is distributed as beneficiary income, the trustee is a single counted owner. The only viable alternative to counting trustees in these circumstances would be to count settlors, on the assumption that they are the ones ultimately benefitting from the existence of the trust. However, a settlor test would likely be complicated,[20] and not a test that domestic trusts would be likely to have to apply commonly in their day-to-day management of their tax affairs. Consequently, our conclusion is that a trustee should continue to be a separate counted owner in the event that not all income is distributed for the relevant period. As with the proposed revised test for measuring the number of beneficiaries, the test for determining whether a trustee is a counted owner should be modified to focus on all income sources rather than just income from interests in LTCs.

Corporate beneficiaries

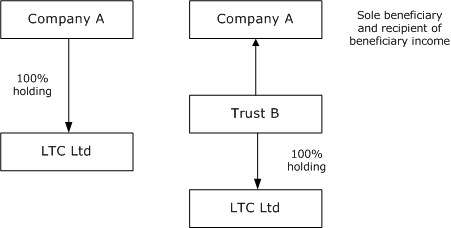

3.31 Corporate beneficiaries are currently permitted. This means that although the structure below on the left is prohibited, the one on the right is permissible. The effect of the two structures appears, however, to be identical:

3.32 It should, however, be noted that if the trust makes a distribution of beneficiary income from LTC interests to the corporate, the corporate is looked through when determining the number of owners. If it is widely held, then LTC status would be revoked.

3.33 In keeping with the exclusion of corporate shareholders, a company should not, in principle, be eligible for LTC status if a trustee shareholder has a corporate (non-LTC) beneficiary. Given, however, that a number of LTCs may already have corporate beneficiaries, we are proposing that the requirement focus on distributions to corporate beneficiaries. The proposal is that LTC status would cease from the beginning of the income year in which a distribution is made to a corporate beneficiary, irrespective of the number of natural person shareholders that it may have.

Example

XYZ Trust owns shares in ABC Limited (a LTC) and makes a distribution of 2016–17 year income to Corporate Limited (a beneficiary of the trust that is not a LTC) in the 2017–18 income year. LTC status would cease from the beginning of the 2017–18 income year.

3.34 In the above example, LTC status is lost in the year of the distribution. Ideally, if the distribution is from beneficiary income, then LTC status should be lost in the year that the beneficiary income is earned, which in the above example would be the 2016–17 income year. Because this would involve additional compliance costs in adjusting past tax payments and returns, we prefer to treat all distributions the same and to base the loss of status on the year of the distribution.

Other shareholders/beneficiaries

3.35 The above approach of looking through to the ultimate beneficiaries should extend to charities and Māori authorities given they are likely to have a wide set of beneficiaries.

Charities

3.36 Although not all charities are trusts, they nevertheless have to be carrying out a charitable purpose.[21] Most also have to meet a public benefit test, which implies that they need to have far more than five beneficiaries. In these circumstances, rather than focusing on whether the charity is a trust, whether and when distributions have been made and whether there are more than five beneficiaries, it seems simpler, from a compliance perspective, to treat all charities the same. The proposal is to exclude charities from being either shareholders in a LTC or beneficiaries of a shareholding trust. This would not preclude charities from operating through other business structures.

3.37 LTCs or shareholding trusts may wish to alternatively make charitable donations. Generally, we do not consider that such charitable donations made in the normal course of business would be a problem. The only concern would be when regular donations were used as a proxy for LTC ownership. Given that we do not want to discourage genuine charitable donations, we consider that there may be merit in having an explicit safe-harbour rule to provide greater certainty. The rule would in effect allow a shareholding trust to donate up to 10 percent of the net income it receives from its look-through interest in any given year to charitable entities without bringing into question the status of the LTC.

Māori authorities

3.38 Māori authorities similarly have a wide number of beneficiaries and, therefore, should also automatically be precluded from being shareholders in a LTC, either directly or indirectly. An implication would be that a Māori authority’s separate corporate business activity would be taxed at the standard company rate of 28%, as intended, rather than at the Māori authority rate of 17.5%.

3.39 Our understanding is that these proposed restrictions would not have a significant impact on either charities or Māori authorities, but feedback on this point is invited.

[15] Loss retailing is a form of loss trading. It occurs when schemes are marketed to portfolio investors which produce significant upfront tax deductions to be applied against the investors’ other income. Those losses typically exceed the amounts at risk.

[16] See Tax Information Bulletin Vol. 23, No. 1, February 2011.

[17] Of the 46,025 LTCs that filed an IR7L for 2013, 30 percent reported having just one ‘owner’ while 92.5 percent reported having either one or two ‘owners’. This seems to be largely in line with data on closely held companies more generally. A 2006 study on closely held companies indicated that of the 431,000 companies registered at the Companies Office, nearly 95 percent had five or fewer shareholders, with 140,000 having only one shareholder (33 percent of all companies) 186,000 having two shareholders (43 percent) and 80,000 having three to five shareholders (18 percent). See M. Farrington A Closely held Companies Act for New Zealand, submitted as part of the LLM programme at Victoria University of Wellington, (2007) 38 VUWLR.

[18] For example, by taking a shareholding in a LTC, a LTC loss could be passed through to the company and used to shelter company income from tax, without the company incurring the underlying economic loss.

[19] The purpose of the Limitations Act is to promote greater certainty by preventing claims being brought against a person or business after a period of time (generally six years), but at the same time the business has to keep records for that period so that the relevant information is available should a claim be brought within that time period.

[20] For example, there may not be robust records around all situations when a person might have become a deemed settlor for tax purposes.

[21] The definition of “charitable purpose” in the Income Tax Act reflects general charities law, which is that the purpose has to be one of the following: the relief of poverty, the advancement of education or religion, or any other matter beneficial to the community. These purposes are commonly referred to as the four “heads” of charity. Except in the case of the relief of poverty, the public benefit test must also be satisfied. That test is that those benefiting must be the public or an appreciably significant section of the public.