Introduction

Background

New Zealand, in common with many other jurisdictions, has a regime in place which requires tax to be paid throughout the year as profits arise based on an estimation of total annual profit. Under this regime, provisional tax is required to be paid by taxpayers (including companies and individuals) if their residual tax liability for the income year is over a certain level.[1] The provisional tax is payable in three equal instalments throughout the year.

Given the volatility of business profits, IR allows three methods for taxpayers to calculate the amount of provisional tax that is payable for an income year. Taxpayers have the option to choose one of the methods outlined below.

- The “standard calculation” method is the default calculation method which bases the provisional tax payable for the year on a percentage uplift of the most recent residual income tax.

- Taxpayers may base payments on their own estimates of actual profit levels.

- Taxpayers may base payments on a percentage of their GST taxable supplies (“GST ratio method”).

How to ensure taxpayers make accurate provisional tax payments throughout the year?

A combined regime that imposes interest (referred to as use-of-money interest or “UOMI”) and/or penalties is in place to ensure taxpayers are incentivised to make accurate provisional tax payments. Broadly, penalties are imposed if payments are made late[2] or if the amount of provisional tax paid is not a reasonable estimate of tax payable.[3]

UOMI is payable or receivable to the extent that actual taxable income is more or less than the estimated amount, therefore resulting in an underpayment or overpayment of provisional tax. The variability in business profits means that UOMI often arises even if detailed estimate calculations are undertaken by taxpayers.

The UOMI rate-setting framework is very much focused on ensuring the right incentives are in place to encourage taxpayers to pay the right amount of tax at the right time. The underpayment rate attempts to reflect the fact that the government is an involuntary and unsecured lender, and is unable to assess the actual credit-worthiness of each taxpayer. The overpayment rate is designed to discourage taxpayers from using IR as an investment opportunity.

The underpayment UOMI rate is set using the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) floating first mortgage new customer housing rate, plus 250 basis points.[4] The overpayment rate is based on the RBNZ 90-day bank bill rate, minus 100 basis points. Linking UOMI rates to RBNZ rates ensures that the UOMI rates reflect overall movements in market interest rates. The current UOMI rate for the underpayment of tax is 8.4% per annum, and for the overpayment of tax is 1.75% per annum. There is a significant differential between the underpayment and overpayment rates of 6.65%.

This differential has remained relatively consistent over the years. The table below summarises the UOMI rates for the underpayment and overpayment of tax over the last 8 years.

| Period | Underpayment rate (%) |

Overpayment rate (%) |

Differential between underpayment and overpayment |

|---|---|---|---|

| From 8 May 2012 | 8.40 | 1.75 | 6.65 |

| From 16 January 2011 | 8.89 | 2.18 | 6.71 |

| From 29 June 2009 | 8.91 | 1.82 | 7.09 |

| From 1 March 2009 | 9.73 | 4.23 | 5.50 |

| From 8 March 2007 | 14.24 | 6.66 | 7.58 |

| From 8 March 2005 | 13.08 | 5.71 | 7.37 |

Why introduce tax pooling?

In 2001 the Government released a discussion document, “More time for business”, which looked at tax simplification from the point of view of small businesses. The discussion document considered a number of options for simplifying the provisional tax rules to give taxpayers more certainty, and to minimise exposure to UOMI while still incentivising taxpayers to pay the correct amount of tax.

The proposals were developed in response to sustained concerns about the penal impact of UOMI from organisations such as the Institute of Chartered Accountants of New Zealand (as it was then).

Tax pooling was one of the options proposed in the discussion document. Tax pooling was expected to allow businesses to pool their provisional tax payments together so that underpayments by some in the pool could be offset against overpayments by others in the same pool.

The intended result of tax pooling was summarised as follows:

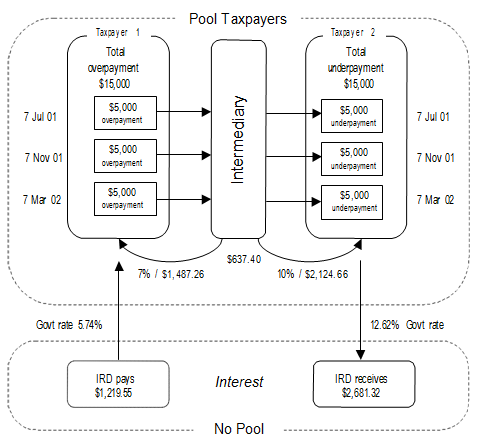

HOW POOLING WOULD WORK

In the example, Taxpayer 1 who overpays would have received $1,219 of UOMI for their overpayment from IR, but instead receives $1,487 from the Intermediary by paying their provisional tax through the Intermediary.

Taxpayer 1 is better off by $268. Taxpayer 2 who underpays would have had to pay $2,681 of UOMI to IR, but instead pays $2,124 to the Intermediary. Taxpayer 2 is better off by $557.

The Intermediary would gain $637 from the opportunity to manage the arbitrage between those in a pool who overpay and those who underpay.

Tax pooling was implemented as part of the tax simplification measures undertaken in 2002.

Policy rationale for tax pooling

Officials acknowledged that the provisional tax rules often resulted in uncertainty for businesses as they operate on the premise that businesses are able to correctly estimate their income for the year. The result of not getting the estimation right will mean the taxpayer overpays or underpays their tax for the year both of which have financial consequences for the business.

Overpayment of provisional tax results in money that a business could use in their business to be “deposited” with IR at a cost to the business. Underpayment of provisional tax means businesses have to face an unexpected interest charge (UOMI). This issue is further exacerbated in that many taxpayers consider that the UOMI rate for overpayment is too low (i.e. does not adequately compensate the business) and the rate it charges on underpayment is too high.

Changing the UOMI was not a feasible option...

It is likely that reducing the UOMI rate differential (for example reducing the underpayment rate) would have alleviated some of the concerns raised by taxpayers in respect of the application of UOMI.

However, in the 2001 discussion document dismissed a change to the UOMI rates as it was considered to be unworkable. In particular, it emphasised that the underpayment rate needs to be set high enough so that there are appropriate incentives in place to ensure taxpayers pay the right amount of tax at the right time. It was further suggested that if the underpayment rate was reduced, an additional penalty may be required to apply to underpayments to ensure the right incentives are in place to encourage compliance from taxpayers.

Although a change of UOMI was swiftly dismissed by IR, the Treasury has subsequently questioned the efficiency of using tax pooling as a way to address the perception of high UOMI underpayment rates and uncertainty in determining provisional tax obligations. It instead favoured a review of the UOMI and provisional tax regimes with a view to making it more certain and acceptable to taxpayers thereby removing the need for a tax pooling regime.

…therefore tax pooling was introduced

Tax pooling was introduced as a way to provide some relief of the financial impact UOMI rules have on businesses as a result of the uncertainty they face in trying to estimate their provisional tax liability without changing the UOMI rates. The UOMI costs faced by taxpayers who participate in tax pooling was expected to more readily reflect the true commercial cost of borrowing or lending by the taxpayer concerned.

In short, tax pooling was intended to provide an opportunity for taxpayers to manage their tax payment risks. It would do so by allowing businesses to pool their provisional tax payments with those of other businesses, with the result that underpayments would be offset by overpayments within the same pool.

The Government also expected to benefit from the introduction of tax pooling. In particular, the government would be seen to have taken a concrete step to address concerns over the UOMI interest rate setting process, by opening up an opportunity for taxpayers to reduce their costs. The sustainability of the then UOMI rate setting processes would also be strengthened.

Tax pooling has evolved over time

While the policy rationale for tax pooling has remained the same, a number of changes have been made to the regime since its introduction in 2003. In particular, a review of the legislation applying to tax pooling intermediaries was undertaken to ensure the rules were working as intended. As a result of the review a number of amendments were made to the tax pooling legislation in 2009 and in 2011.

The changes include:

- extending tax pooling to reassessments (including reassessment that arise as a result of a voluntary disclosure or the resolution of a dispute)

- extending tax pooling to voluntary disclosures for certain non-income tax obligations (i.e. GST, PAYE or FBT) where no previous assessment has been made

- providing discretion for IR (i.e. the Commissioner) to allow taxpayers to use tax pooling for certain income tax or RWT voluntary disclosures where no return has previously been filed

- enabling pooling funds to be transferred between intermediaries

- allowing all taxpayers to make deposits into tax pooling accounts

- extending the time limit available to satisfy an obligation to pay provisional or terminal tax to 75 days (note that for reassessments the time limit remains at 60 days from the date of the reassessment)

- removing this time limit for meeting provisional or terminal tax obligations when taxpayers use their own deposited funds, provided the return was filed on time.

In addition to this general review of the tax pooling legislation, IR also conducted a specific review of the operation of the Commissioner’s discretion to allow the use of tax pooling funds for certain income tax or RWT voluntary disclosures where no return has previously been filed. The review concluded that the discretion is operating as intended and should be retained.

1 The majority of individual taxpayers do not fall into the provisional tax regime as tax is fully withheld at source on income received by wage and salary earners and bank interest.

2 The late payment penalty has two components:

- Initial late payment penalty – 1% is added on the day after the due date then a further 4% is added to the unpaid tax and the late payment penalty already imposed at the end of the seventh day after the due date; and

- Incremental late payment penalty - 1% is added the day after the end of the month following the imposition of the initial late payment penalty. The incremental late payment penalty is calculated based on the unpaid tax and any late payment penalties already imposed.

3 Shortfall penalties that can apply can be between 20% to 150% of the unpaid tax.

4 The current method in setting the underpayment UOMI rate was introduced in 2009. Prior to that, the rate was set using the Reserve Bank of New Zealand 90-day bank rate plus 450 basis points.