4. Administration of the tax system

A well functioning tax system that supports the Government’s fiscal, economic and social objectives requires good tax policy settings. But good tax policy alone is not sufficient. It is necessary to consider as a whole the entire tax system, including how the policy is applied in practice and how the tax system is administered. A good tax system requires good tax administration as well as good tax policy. In New Zealand responsibility for administering the tax system falls largely on Inland Revenue. The issues and challenges of that role are the focus of this chapter.

After briefly summarising Inland Revenue’s core functions and outputs, this chapter outlines our view on what Inland Revenue needs to deliver if it is to support a good tax system. It then assesses how Inland Revenue measures up against that requirement. Various measures indicate we are currently performing well in carrying out our core tasks. However, that needs to be caveated by our need to manage some key pressure points: continuing demand for our services, issues with our core IT systems and the need for improved management of the portfolio of Crown debt and receivables that Inland Revenue manages. As we look into the future we are likely to need to manage these pressure points in a constrained fiscal environment with a significant reduction in our Vote baselines. In addition, we are in the process of significant business change as we respond to technological change and changes in service expectations. This will require significant changes in the way Inland Revenue operates, supported by some policy changes that may be controversial, and a substantial investment in our IT systems. In this environment Inland Revenue will be constrained over the next few years in the extent to which we will be able to deliver policy changes that have complex implications for our core IT system. Finally, the chapter notes that re-establishing ourselves in Christchurch following the Canterbury earthquake is an urgent priority for Inland Revenue.

Core functions and outputs

For the year ended 30 June 2011, Inland Revenue collected 70 percent of total Government revenue and 77 percent of total tax revenue.[16] Total staff at 30 June 2011 numbered 5,511 (measured in full-time staff equivalents).

Constitutionally, tax can only be levied in accordance with laws enacted by Parliament. Inland Revenue has an obligation to levy tax in accordance with the law to the best of our ability. We also have an important obligation to maintain confidentiality of people's tax affairs. The Commissioner has statutory independence from Ministers to ensure we are able to levy tax and carry out our duties independently. We also administer KiwiSaver and a range of social policy initiatives which are not part of the tax system but are generally administered using the infrastructure put in place to collect tax. The Policy Advice Division of Inland Revenue, jointly with the Treasury, provides advice to Ministers on tax policy and assists with the management of tax legislation through Parliament.

What Inland Revenue needs to be

For New Zealand to have a good tax system, Inland Revenue needs to be a world-class revenue organisation, recognised for service and excellence. To achieve this we need to provide:

a) Service with speed and efficiency

Obligations and entitlements should be established and finalised as quickly as possible. Without speed and certainty compliance costs and risk increase, adversely affecting productivity by reducing incentives to work, save and invest. A tax system with speed and certainty makes New Zealand a more desirable place to invest into and out from.

b) Compliance with the law and value for money

This provides tax revenue at the lowest possible cost, thereby supporting the Government’s fiscal objectives and in turn reducing New Zealand’s external vulnerability while maintaining the social services that the country provides.

How Inland Revenue measures up

Being a world-class revenue organisation is a challenging objective. In general Inland Revenue is a high-performing department.

A formal review of Inland Revenue was carried out in May 2011 under the Performance Improvement Framework by the State Services Commission, the Treasury and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Review concluded that:

Over the range of services it delivers, Inland Revenue is, on balance, a very well managed department. It displays admirable strengths in both its policy advice functions and in much of its operations. It has a big brain and a strong body. (Page 5.)

Of the 33 performance ratings made, Inland Revenue was ruled:

| Strong | 10 |

| Well placed | 16 |

| Needing development | 4 |

| Weak | 0 |

The areas rated as needing development largely related to Inland Revenue’s ability to manage ongoing business change and, in particular, its business transformation challenge — including upgrading its technological capability. The other main area of concern was debt management.

Inland Revenue recently participated in an international tax administration benchmarking exercise coordinated by the United Kingdom Revenue and Customs Authority and run by CapGemini Consulting. We were ranked in the top three (out of 10 participating countries) for 26 of the 42 indicators used in the benchmarking study that are comparable and allow robust interpretation. Inland Revenue was the highest ranking tax administration for seven of these indicators.

Over recent years, significant progress has been made and the department has put in a solid performance. While the OECD expressed some reservations about the robustness of the analysis, a recent OECD study (based on the 2008–09 data) suggests that New Zealand performs somewhat better than average on administration costs for revenue collected (88 cents to collect $100 of revenue). The results of this study are discussed in more detail in chapter 3.

Also, Inland Revenue’s own surveys of customers show a reasonably high degree of satisfaction with Inland Revenue’s performance. For example, the survey results for the 2010–11 year indicate that:

- 87% of respondents were satisfied or very satisfied with the overall quality of Inland Revenue’s service in the voice, counter, and correspondence channels; and

- 92% of respondents were satisfied or very satisfied with Inland Revenue’s online service channel.[17]

In addition, New Zealand Management Magazine this year ranked Inland Revenue as the second most reputable government department. This was based on a range of criteria, including having a clear and compelling vision for the future and consistently delivering customer promises and service.

Pressure points

The overall picture is of a well functioning department that plays a critical role for the Government and is one of the main interfaces between the Government and the public. Nevertheless, there is significant room to continue improving performance, pressure points that need to be managed in doing so, and considerable opportunities and challenges over the next few years. These are managing growth in demand for services, systems problems and better management of Crown debt and receivables Inland Revenue administers.

Growth in demand

Inland Revenue’s role has expanded over recent years. In the early 1990s Inland Revenue became responsible for administering the child support and student loan schemes. More recently we have taken on some significant new or changed Government programmes, including: the enhanced programme of Working for Families tax credits, paid parental leave, interest-free student loans and KiwiSaver.

In addition, there has been a substantial increase in the underlying demand for more traditional services as indicated in table 3.

| Description | 2005–2006 | 2010–11 | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer base | 6.3m | 7.1m | +0.8m | 12.7% |

| Phone calls answered | 3.7m | 3.9m | +0.2m | 5.4% |

| Self-help services | 5.1m | 16.0m | +10.9m | 213.7% |

| Tax returns processed | 7.7m | 8.0m | +0.3m | 3.9% |

| Payments processed | 7.7m | 8.1m | +0.4m | 5.2% |

| Total tax revenue* | $46.8b | $46.8b | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total tax debt | $3.5b | $5.5b | +$2b | 57.1% |

| Revenue assessed via audit | $1.0b | $1.4b | +$0.4b | 40.0% |

| Cash collected – debt activities** | $1.7b | $2.5b | +$0.8b | 47.1% |

| Student Loans collections | $487m | $691m | +$204m | 41.9% |

| WfFTC disbursements | $1.5b | $2.7b | +$1.0b | 80.0% |

| KiwiSaver funds to providers | nil | $2.9b | n/a | n/a |

| Child Support collections | $349m | $412m | +$63m | 18.1% |

* Note: During this period total tax revenue peaked at $51.9 billion in 2007–08 (11% up on 2005–06).

** Includes cash received from tax pooling.

Also, the way people want to interact with Inland Revenue is changing. Increasingly people expect to be able to deal with us electronically. This is illustrated by the growth in registrations for online services – as indicated in table 4 below.

| 2008–2009 | 2009–10 | 2010–11 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total registrations for online services (cumulative) | 360,003 | 619,932 | 964,904 |

To a significant extent this increase in demand has been met from Inland Revenue’s existing funding through ongoing efficiencies.

System issues

Inland Revenue’s IT systems are based around FIRST, an IT system built specifically for Inland Revenue in the early 1990s. While this system continues to operate efficiently in delivering its core tax functions, the growing ambit of Inland Revenue activities and changes in public expectations have resulted in the system becoming a significant constraint on the department’s operations. This can only be addressed by a programme that combines progressive technological and systems changes with a transformation in the operation of Inland Revenue’s business (involving people, processes and policy). This will inevitably take time. This means that over the next few years Inland Revenue’s ability to deliver quickly any policy changes with complex system implications will be especially constrained. The issue is covered in more detail below under the section on “Business change”.

Debt

Inland Revenue administers a portfolio of Crown debt and receivables totalling $23.4 billion (June 2011). This is obviously significant in terms of the Government’s overall balance sheet. The nominal value of the debt is broken down as follows:

| $ billion | |

|---|---|

| Student Loans[18] | 10.7 |

| Child Support penalties | 1.7 |

| Tax yet to be due | 5.5 |

| Overdue tax | 5.5 ____ |

| 23.4 |

Overdue tax has increased from $2.9 billion in June 2005 to $5.5 billion (an increase of 89%). In 2009 the Auditor-General recommended a number of measures to improve Inland Revenue’s debt management. These are being implemented and in Budget 2010 Inland Revenue was provided with additional funding of $10.2 million per annum in 2010–11 to improve debt collection, increasing to $17 million in the out years. This has enabled improved performance in this area. During 2010–11 we collected $115 million in cash against a target of $100 million, with a return of $9.50 for every $1 spent (above the target of $7.70 for every $1 spent).

The focus is on preventing people falling into debt and contacting them early to assist them if they go into debt. Debt aged less than one year has decreased by 8.2 percent over the last year, but total debt still increased by 7 percent in 2010–11. This needs to be an area of continued focus.

Delivering value in a changing environment

In addition to managing these pressure points, to build a world-class revenue organisation we need to capitalise on opportunities and rise to the challenges of:

a) the fiscal environment; and

b) business change at a time of rapid technological advances.

The fiscal environment – delivering more for less

The Government’s fiscal position is likely to be significantly under pressure for some time. To help manage this, departments (including Inland Revenue) are expected to deliver more for less.

Inland Revenue reacted quickly to lower its administrative costs in response to the Government’s tight fiscal position. Over the last three years we have:

- delivered $116 million of gross value for money savings — returning $36 million to the Crown and reinvesting $80 million back into Inland Revenue to manage cost pressures and target key strategic priorities;

- reduced our staffing levels by 630 FTEs[19] (excluding Budget 2010 initiatives); and

- achieved 89 percent of performance standards in 2008–09, 97 percent in 2009–10 and 84 percent 2010–11 (the year the Christchurch earthquake affected the achievement of some performance measures).

Our current and forecast baselines for Vote Revenue fall significantly over the next four years. Within these reduced baselines we are required to absorb future remuneration pressures. This is significant given that salaries and wages make up more than half of our baseline expenditure. In addition, fixed costs that are difficult to reduce (depreciation, capital charge, accommodation rental and information technology costs) make up more than one-third of our baseline.

To date we have been successful in providing efficiency savings by making existing policy and operational frameworks more efficient. For example, we are in the process of reviewing where our staff are located to ensure a level of service appropriate to local areas while maximising economies of scale. We expect ongoing savings from these and similar measures.

Nevertheless, the level of efficiencies necessary to meet future baseline pressures is likely to require changes in some policies. This will allow us to capitalise on the efficiency opportunities that technological change provides. In many cases it is much more efficient for Inland Revenue to deal with customers and intermediaries through electronic channels rather than by paper, telephone or counter services. The average service costs for customers per contact vary significantly as illustrated below:[20]

| Telephone | $28.84 |

| Correspondence | $40.45 |

| Counter | $35.12 |

The benefits and savings available through electronic contact should be significant, but they would be considerably reduced (and may even add costs) if existing communication channels remain at current levels as new electronic channels are developed. Some legislative or policy changes may therefore be required (for example, no longer issuing refunds by cheque). These policy changes are likely to be controversial.

We are mindful that our efficiency targets cannot be met at the cost of lower tax collections. Our tax compliance strategy is based on ensuring that long-term sustained voluntary compliance is the behavioural norm. We rely on taxpayers making their payments and claiming their entitlements in full and at the right time — and most of them do. Times of significant change for Inland Revenue, such as we are currently experiencing, can pose some risks to compliance. However, our ability to maximise voluntary compliance and address non-compliance is increasing in terms of both our capabilities and the technologies available. In particular, our compliance responses are becoming increasingly targeted and effective. There are opportunities, through increased investment by the Government, to raise revenue and in doing so also increase the integrity of the tax system.

In addition, over the last 18 months we have been working with the Ministry of Social Development and the Department of Internal Affairs to explore joint opportunities for a more efficient and effective approach to service delivery. A guiding principle for this work is building services around customer need, rather than the structure of government agencies. Jurisdictions such as Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom have shown that improved customer service and more efficient investment are possible from service transformation interventions.

The Service Transformation Programme, led by the Ministry of Social Development and supported by the Department of Internal Affairs and Inland Revenue, was recently established. In the short term, the programme will direct the development of best practice service delivery technology and processes through a common standards approach, and the alignment of service delivery initiatives across the three agencies. It is intended that other government agencies will become involved with the programme in future if the approach proves to be successful.

In addition to the core programme, Inland Revenue is implementing a number of service transformation initiatives. These include iGovt logons, and a joint call centre in Christchurch with the Ministry of Social Development. Service Transformation is a priority for us and should result in improvements to the way we deliver services.

Business change

To meet the demands of a changing environment our business needs to be transformed. For this transformation to be successful, system changes and operational changes are required. To enable operational change some policy changes will also be necessary.

System changes

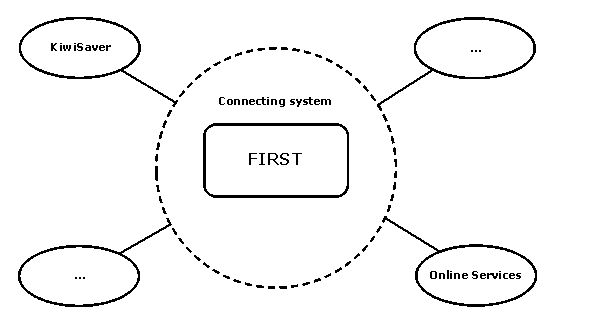

Revenue authorities throughout the world are high and increasing users of information technology. Inland Revenue is no exception. Our system is based on FIRST — an integrated system that was purpose-built for Inland Revenue in the early 1990s. FIRST is our core operating system. It identifies and registers taxpayers by number, calculates tax liabilities, amounts owing or refunds due, handles returns, correspondence and ensures that tax totals are recorded for Crown revenue purposes. Connected to this core system are separate satellite systems dealing with, for example, KiwiSaver and online services used by tax agents and taxpayers, as shown in diagram 1.

Diagram 1: FIRST and satellite systems

The main concerns are:

- FIRST was purpose-built for Inland Revenue. The modern approach is to use general systems with multiple users – which provides greater efficiency and reliability.

- FIRST is an integrated system. A change in one part of it can affect any other part (and any part of the satellite systems to which it is connected). It is like a house full of appliances connected to electricity by a cable full of intertwined wires. When you change or disconnect one wire it can be difficult to tell what appliances in the house will be affected. Careful testing is required for every change to the FIRST system. This makes changes to implement new policies time-consuming and expensive.

- FIRST is an old system. When it was built Microsoft was a start-up firm and there was no internet. It does not therefore cope well with demands for online access.

- The system connecting FIRST with the satellite systems has reached its use-by-date and needs replacement.

- Many of the satellite systems are also old and ill-suited to modern online requirements.

To meet the demands of a world-class revenue organisation, one of the key things we need to do is move, over time, to a new system architecture. Over the last few years we have invested in the key capabilities of the FIRST system and are now satisfied that it can continue to deliver the core functions it was originally designed to deliver for approximately 10 more years. Nevertheless, significant investments in IT will be required over that time to move the system architecture onto a more sustainable basis that can deliver future requirements. Decisions on this will be a key concern for Ministers over the next few years.

Our proposed strategy carried out over the next 10 or so years focuses first on maintaining current systems to support volume growth and ensure stability. This will include replacing the system that connects FIRST with the satellite systems. The next priority is disentangling the integrated nature of the FIRST system, making the overall system more modular so that changes to one part do not affect others — in effect separating the intertwined wires so that each can be worked upon individually. This will enable us to implement policy changes in a more efficient and timely manner. Once that is achieved, current constraints on implementing policy changes (current requirements will consume much of our resources until 2014) will be relaxed. We will then be able to use this modernised IT architecture to deliver better and more efficient services to the public.

There is a difficult balancing act here. We need to continue to develop within the FIRST system to ensure that current services can be delivered (for example, collection of student loans and child support), at the same time redeveloping FIRST to meet the challenges of a new environment. Until substantial progress is made on this programme Inland Revenue will be significantly constrained in its ability to deliver policy changes with complex system requirements or to capitalise on opportunities electronic communications offer to deliver efficiency savings to meet budgetary requirements.

Operational changes

Our view is that the focus of Inland Revenue should increasingly move away from the management of routine administrative processes towards activities that add value, such as faster responses and giving customers greater certainty. This means that, over time, resources should move from correcting inaccuracies in data and processes to getting it right upfront and using those resources to identify and correct non-compliance and provide better support to taxpayers.

For this to be achieved Inland Revenue needs operational excellence in the management of the administrative processes which are the bulk of our business. Without these core processes running smoothly and professionally it will not be possible to achieve the efficiency outcomes that the Government and Inland Revenue desire from tax administration.

There are a number of measures underway to support operational excellence. Inland Revenue is moving to deploy operational management tools to improve services and streamline process. These tools will allow us to improve efficiency and to reduce duplication. They will also allow us to meet the operational savings targets set by the Government. Using these tools will require significant change in Inland Revenue’s structure and processes and there will be a need to focus on these changes in the near term.

Inland Revenue is also changing to provide front-line services that meet local needs. This means providing local counter services when this is appropriate and serves a local need. Services that do not need to be performed locally are being managed centrally. This enhances efficiency and provides operational savings to support the Government’s goals.

As well as these operational improvements it is necessary to manage the continuing pressure associated with our annual peak season — which includes most of the first quarter of each financial year. While increased management focus on this area in recent years has ensured success, it has come at the cost of affecting delivery of other goals. It requires the diversion of specialist resources from other business areas (such as correspondence, debt and return collection) to help respond to peak season demand for telephone services. This work distracts from delivering the high-value activities desirable in an efficient tax administration.

Operational excellence will not be achieved by continuing with current processes. We will need to capitalise on opportunities created by technological change. These include automating routine processes to allow both taxpayers and Inland Revenue to focus on value-added activities, using e-channels and providing taxpayers with efficient self-management options.

Change will be required not only by Inland Revenue, but also our customers and third parties such as software developers. Technology is changing quickly with increased flexibility to tailor products to individual needs. Inland Revenue cannot realistically provide the flexibility and targeted products now expected. Inland Revenue therefore needs to work closely with the private sector, including commercial entities such as payroll firms that will intermediate between Inland Revenue systems and the various individual needs of the public. To make this a reality, policy changes will be required.

We also need to continue to find ways of working more efficiently across government — including working more closely with other government departments. Where appropriate, this could include greater sharing of information. While further progress in this area is worth exploring, there are a number of complex issues that need to be carefully considered — including taxpayer secrecy and IT integration concerns.

Canterbury earthquake

The Canterbury earthquake created an urgent need for Inland Revenue to respond to problems faced by taxpayers. Inland Revenue responded quickly with Orders in Council and legislative amendments dealing with the most urgent problems facing taxpayers.

At the same time our own operations were severely affected. Christchurch is Inland Revenue’s second largest operation with approximately 700 employees. Christchurch staff were operating from a four-year old, seven-story building. It suffered moderate damage in February and June and has been unoccupied since February. It remains in the CBD red zone. Required repairs include a minor re-levelling of the building core by 8cm which has not been done in a building of this size in New Zealand. Timeframes for this repair work and getting the building operational are uncertain.

Inland Revenue is currently operating from 23 temporary sites, providing seating for nearly 700 staff. Our Contact Centre of 150 agents has not been operational since February which has required work to be relocated nationally. There are also around 60 staff on secondment to a range of agencies, including the Ministry of Social Development and the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority. In addition, many staff are working from home.

Re-establishing ourselves in Christchurch continues to be an urgent priority for the department.

16 Notes to the Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand; page 53.

17 The Online Customer Satisfaction Survey began in the second quarter of the 2010-11 year.

18 The $10.7 billion is the amount of the student loan balance – not the arrears.

19 For the period June 2009 to June 2011.

20 The average service costs per electronic contact are not currently available.