Child support scheme reform

AGENCY DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This regulatory impact statement has been prepared by Inland Revenue.

The statement is detailed since it deals with a large number of options for the potential reform of the New Zealand child support scheme, which will have implications for a significant number of children and parents. The statement provides an analysis of the existing child support rules and considers whether alternative measures could better provide for the interests of children involved in the scheme.

We believe that the current child support scheme does not always adequately take the individual circumstances of parents into account, and this can make some parents less willing to meet their payment obligations.

There has been consultation with a range of Government agencies on child support issues over a period of time. This consultation was with the Ministry of Social Development, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, the Treasury and the Families Commission. There has also been significant public consultation on options for child support reform.

The changes recommended to the child support formula would have financial implications for some parents. However, it is estimated that over 82 percent of current child support received and about 74 percent of child support paid would therefore either be unaffected or affected to the extent of plus or minus $66 per month (plus or minus $800 per year).

Inland Revenue is of the view that there are no significant constraints, caveats and uncertainties concerning the regulatory analysis undertaken. None of the policy options would restrict market competition, reduce the incentives for businesses to innovate and invest, unduly impair private property rights or override fundamental common law principles. One of the policy options would, however, impose minor additional costs on some businesses that employ parents who pay child support, although these additional costs will not be significant and already form part of the existing PAYE processes.

Craig Latham

Group Manager, Policy

Inland Revenue

26 July 2011

STATUS QUO AND PROBLEM

Background

1. The New Zealand child support scheme helps to provide financial support for over 210,000 children. The scheme was established by the Child Support Act 1991, which revised the rules relating to child maintenance when agreement between parents proves difficult or when the receiving parent is a beneficiary.

2. One of the Government’s key social policy objectives is to ensure that New Zealanders have an equal opportunity to participate in and contribute to society. This includes providing a safety net through the benefit system for those who are unable, for various reasons, to financially support themselves. In the context of child support, this means that child support payments are collected and delivered for the benefit of the children that they are intended for, and they ensure that parents do not pass their financial responsibilities to maintain their children onto other members of society. This is why parents can be liable for child support even when the receiving parent receives a state-provided benefit.

3. The child support scheme is needed when parents cannot mutually agree on their relative financial contributions to support their children (or when the receiving parent receives a state-provided benefit). Although many parents reach private agreement on their financial contributions and care arrangements, and outcomes may be more satisfactory if they do, many cannot achieve agreement. A back-stop is needed in these circumstances, and this is provided by the child support scheme.

4. The scheme is not, however, intended to provide full financial compensation to offset any decline in family members’ living standards as a result of parents living apart. A decline in living standards is often inevitable in these circumstances. There is often a duplication of housing and related costs, such as utilities and household furnishings. There are also additional costs associated with children visiting or staying with the paying parent, such as play and study space, toys and play equipment, and transport costs.

5. Given its importance and impact on New Zealand society, it is essential that the child support scheme operates as effectively as possible, and in the best interests of the children involved.

How child support works

6. The child support scheme is administered by Inland Revenue, which is responsible for both assessing contributions and collecting payments. The child support scheme is voluntary for parents unless the caregiver is receiving a sole-parent benefit.

7. When an application for child support has been properly made, the Commissioner of Inland Revenue is bound to accept it. Liability then arises under a simple administrative formula. The parent with the liability makes his or her payment to the Crown which then passes it to the person who has primary care for the child. In most cases this will be the child’s other parent. If the caregiver is receiving a sole-parent benefit, the child support payments are retained by the Crown to help defray the cost of the benefit and any excess is passed on to the caregiver.

The standard formula

8. The current formula for calculating child support is:

(a – b) x c

where:

“a” is the child support income amount;

“b” is the living allowance; and

“c” is the child support percentage.

9. For most paying parents, the child support income amount is their taxable income in the preceding income year. The maximum child support income that can be assessed is set at two and a half times the national average earnings for men and women as at mid-February of the tax year immediately preceding the most recent tax year. The maximum is currently $121,833.

10. There are six separate living allowance levels, ranging from $14,281 to $36,417, depending on whether the paying parent is living alone or with a partner and/or other children. The allowance is based on benefit rates plus a set amount for each dependent child up to a maximum of four children.

11. Once the living allowance has been deducted from child support income, the product is multiplied by the child support percentage relevant for the number of children being supported. The standard percentages are:

| No. of children | Child support percentage – sole care |

|---|---|

| 1 | 18 |

| 2 | 24 |

| 3 | 27 |

| 4 or more | 30 |

12. There is a minimum amount of child support payable each year. The current minimum amount is $848.

Shared care

13. The child support percentages are reduced if parents share the care of their child. Under the Child Support Act, care of a child is regarded as being shared when each provider of care shares the ongoing daily care of the child “substantially equally” with the other care provider. A paying parent who looks after a child for at least 40 percent of nights in a year is considered to meet this test.

14. If a parent does not meet this test, he or she may qualify under an alternative test based on the courts’ interpretation of “substantially equally”. This requires at least 50 percent of the responsibility in relation to the factors constituting care other than overnight care.

15. If shared care is established, parents can cross-apply for child support. This involves respective liabilities being offset to produce a net amount for one parent to pay.

Administrative reviews

16. If either parent considers that the amount payable under the formula is not appropriate, they can apply for an administrative review under one or more of 10 grounds set out in the Child Support Act. The Commissioner of Inland Revenue then appoints an independent review officer experienced in relevant cases to consider the application. The review officer makes a recommendation on whether departure from the child support formula assessment is warranted. The Commissioner has the discretion to either accept the review officer’s recommendation or conduct a rehearing.

Reasons for the review

17. Although the current child support scheme provides a relatively straightforward way of calculating child support liability for the majority of parents, there are some major concerns that seem to be affecting an increasing number of parents (and therefore children).

18. The primary assumption under the current scheme is that the paying parent is the sole income earner and that the receiving parent is the main care provider. However, when parents live apart, there is a greatly increased emphasis on shared parental responsibility and both parents remaining actively involved in their children’s lives. Participation rates of both parents, particularly in part-time work, has also increased since the scheme was introduced, resulting in the principal carer of the children now being more likely to be in paid work.

19. Escalating levels of accumulated child support debt, relating in particular to child support penalties, is increasingly becoming an issue.

20. Many people therefore consider that the scheme is now, in many cases, out of date. This undermines some parents’ incentives to meet their child support obligations, and is detrimental to the wellbeing of some children.

Specific policy problems

21. Some paying parents are concerned that the scheme does not take account of their particular circumstances. For example, they may share the care and costs of their children but have arrangements that do not qualify as “shared care” for the purposes of the child support formula. Parents may also be in a situation where their income, on which child support liability is calculated, is substantially less than that of the receiving parent.

22. Receiving parents, on the other hand, are concerned about non-payment of child support on the part of the paying parent, or the instability of payments. Some consider current payments to be insufficient to meet the costs of caring for their children and do not feel that they accurately reflect the true expenditure of raising children in New Zealand. They may also be concerned about delays in receiving payments.

23. For these reasons the Minister of Revenue released a Government discussion document on child support entitled Supporting children in September 2010.[1]

24. The discussion document includes detailed analysis of both the current scheme and options for updating the scheme, including revising the child support formula to better recognise shared care, and to take into account the income of both parents and the current expenditure of raising children in New Zealand. Incentives for making child support payments, and making them on time, are also discussed, along with suggestions about how these could be improved.

25. The main policy problems considered were:

- whether the current child support system accurately reflects the expenditure for raising children in varying family circumstances in New Zealand;

- whether greater levels of shared care and other regular care should be taken into account when calculating child support;

- whether both parents’ income should be taken into account when calculating the child support to be paid;

- whether incentives to make payments can be improved by changing the child support penalty rules and write-off provisions.

26. A dedicated website for online consultation summarised the main options considered in the discussion document and asked readers to respond to a series of questions based on those options. Respondents were also able to provide comments in key areas. Written submissions on the same issues were also received through the normal policy submission process.

OBJECTIVES

27. Two primary objectives have been considered in assessing options for amending the child support scheme. These are:

- To improve the fairness of the child support scheme so that it reflects social and legal changes which have occurred since its introduction in 1992.

- To promote the welfare of the children, in particular by recognising that children are disadvantaged when child support is not paid, or not paid on time.

28. Social changes since the introduction of the scheme mean that there is now a greater emphasis on separated parents sharing the care of their children and there is higher participation in the workforce by receiving parents.

29. The disadvantage when child support is not paid is a financial one (particularly when the receiving parent is not on a sole-parent benefit) which may in turn involve emotional detachment from the parent who is not the primary caregiver. A more transparent system with a better targeted payment and penalties system would encourage, or at least not discourage, parents to pay their child support and would help improve the well-being of their children.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS

30. A number of different options have been considered to address the objectives of the review. These were all discussed in depth in the Supporting children discussion document, and in a subsequent summary feedback document released in July 2011.[2]

31. The purpose of the feedback document was to set out the detailed results of the online consultation. It also provided a summary of the main themes and concerns raised in both the online consultation and in associated written submissions.

32. Broadly speaking, there was majority support for many of the options canvassed, but there were some areas where a significant minority opinion existed. This likely reflects the potential for conflict in the child support area.

33. There were 2,272 participants in the online consultation. They comprised:

- 834 receiving parents (37 percent);

- 753 paying parents (33 percent); and

- 685 “other” parties (30 percent), including those who both pay and receive child support, other family members, members of representative organisations and advocates in child support policy such as lawyers and academics.

34. In order to provide greater context, and a more detailed analysis, the following information on the options considered in this RIS should be read in conjunction with the September 2010 discussion document and the July 2011 summary of feedback.

35. The options to improve on the status quo that have been considered in this RIS are not generally mutually exclusive. They have been placed into the following broad categories:

- key changes to update the child support formula;

- secondary changes to update the child support scheme more generally; and

- changes to amend the payment, penalty and debt rules for child support.

36. The impacts of the options are summarised in the following tables.

| Net assessment of option 4 – a package to update the child support formula (options 1, 1b, 2, 2a, 2c, and 3) | |||||

| Impacts | Meets objectives | Recommendation | |||

| Benefits | Costs | Reflects changes in society? | Incentivises payment? | ||

Revised child support formula that: - uses up-to-date estimates on the expenditure for raising children; - reduces current shared care threshold by adopting a tiered threshold recognising care from 28% of nights; and - takes both parents’ income into account |

Better reflects the true costs of supporting children, the sharing of costs and care Is more transparent and reflective of relative ability to contribute towards children |

More complex to ascertain and administer May reduce work incentives in some circumstances (but increase incentives in others) |

Yes | Yes | Recommended, significant improvement on the status quo |

| Gender and distributional impact of option 4 (a revised child support formula) | |||||

| Unaffected | Receive more / pay less | Receive less / pay more | |||

| Receiving parents | 82,230 (60%) | 24,505 (18%) | 29,776 (22%) | ||

| Paying parents | 57,823 (42%) | 45,997 (34%) | 32,691 (24%) | ||

| Females | 83,039 (59%) | 25,954 (18%) | 31,428 (22%) | ||

| Males | 56,191 (43%) | 44,307 (34%) | 30,750 (23%) | ||

| Net assessment of other recommended options (options 5a, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14a, 14b, 16a, 16b, 17) | |||||

| Option | Impacts | Meets objectives | Recommendation | ||

| Benefits | Costs | Reflects changes in society? | Incentivises payment? | ||

| Secondary changes to update the child support scheme more generally | Better reflects more individual circumstances | More complex to administer | Yes | Yes | Recommended, improves on status quo |

| Changes to amend the payment, penalty and debt rules for child support | Increases incentives to pay Helps prevent escalation of child support debt |

Increased compliance for Inland Revenue Some privacy concerns |

Not applicable | Yes | Recommended, improves on status quo |

| Option | Impacts | Meets objectives | Recommendation | ||

| Benefits | Costs | Reflects changes in society? | Incentivises payment? | ||

| Key changes to update the child support formula | |||||

| 1. Use up-to-date estimates on the expenditure for raising children | Better reflects true costs involved | Yes | Yes | Recommended, together with options 1b, 2, 2a, 2c and 3a (see option 4) | |

| 1a. Use fixed estimates | Would not reflect that costs rise with incomes | No | Generally, no | Not recommended | |

| 1b. Vary estimates depending on age of children | Better reflects true costs incurred | Yes | Generally, yes | Recommended | |

| 1c. Remove income cap | Would not reflect true costs incurred | No | No | Not recommended | |

| 2. Reduce current shared care threshold | Recognises parents who incur significant costs but do not qualify for shared care | Yes | Yes | Recommended, together with options 1, 1b, 2a. 2c and 3a (see option 4) | |

| 2a. Adopt a tiered threshold | Better reflects costs of actual level of care provided Reduces cliff effect |

More complex to ascertain and administer | Yes | Yes | Recommended, as benefits considered to outweigh costs |

| 2b. Recognise care from 14% of nights | Provides more recognition to a greater number of paying parents who care for their children | May provide too much recognition. Greater financial impact for receiving parent and/or Government |

Yes | Yes | Not recommended, as over compensates paying parents in some cases |

| 2c. Recognise care from 28% of nights | Recognises paying parents most impacted by inability to claim shared care under current threshold | Yes | Yes | Recommended | |

| 3. Take both parents’ income into account | More transparent Better reflects relative ability to contribute towards children |

May reduce work incentives in some circumstances (but increase incentives in others) | Yes | Yes | Recommended, together with options 1, 1b, 2, 2a and 2c (see option 4) |

| 3a. Include income of new partners | Would better reflect, in some cases, the support that is available for children | New partners may not financially contribute to their partner’s children Can already be recognised under review process |

Partially | Partially | Not recommended, as administrative review process still available where it is felt that the income of new partners should be included |

| Secondary changes to update the child support scheme more generally | |||||

| 5. Use an alternative to the “nights” test to measure shared care (eg total time or days) | Could provide more recognition in certain cases (eg where there is significant daytime contact) Could provide for greater alignment with Working for Families |

Not as effective in determining care levels in many cases, and more complex Departures already provided as part of administrative review process |

In some cases | In some cases | Not recommended, as no overall improvement against the status quo. |

| 5a. Commissioner discretion to allow departures for significant daytime care | Could provide relief where costs of non overnight care are significant Would provide a simpler process than an administrative review |

Additional compliance for Inland Revenue | Yes | Yes | Recommended, as would provide more flexibility to recognise significant daytime care |

| 6. Allow Inland Revenue to rely on parenting orders and agreements for child support purposes | Would allow for more efficient processing of shared care applications | Would require a new administrative review ground and Inland Revenue discretion to rebut levels of care if orders/agreements not followed in practise | Yes | Yes | Recommended, as benefits considered to outweigh costs |

| 7. Exclude losses and include trustee income in the definition of income for child support | Better reflects real income parents have available to pay child support Counters parents structuring affairs to reduce child support payable More consistent with treatment for some forms of social assistance |

Yes | No | Recommended | |

| 8. Create an administrative review ground when certain re-establishment costs are incurred | Reflects likely patterns of expenditure post separation Increase incentives for parents to provide suitable housing for children |

Yes | Yes | Recommended | |

| 9. Introduce an Inland Revenue discretion to allow certain prescribed payments to count towards a parent’s child support liability | Would provide a greater incentive to pay child support as paying parent knows that payment is directly benefiting children | Increased compliance as costs would need to be of a prescribed type (eg medical costs) or otherwise agreed between parents | Yes | Yes | Recommended, but not if: - child support liabilities have been adjusted to reflect shared care; or - the receiving parent receives a sole-parent benefit only |

| 10. Reduce the qualifying age to 18 | Reflects that children who are 18 and who have left school can work or claim a benefit/ student allowance in their own right | Not applicable | Not applicable | Recommended, as, although it does not specifically meet main objectives, it none the less represents an improvement on the status quo | |

| 11. Place restrictions on who can claim child support | Could address, in a small number of cases, concerns by parents where a teenage child has left home to live with other adults. | Could compromise the ability of children to be cared for by people other than parents when it is in their best interests to do so | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not recommended, but further work to commence with MSD and Justice to see if a suitable appeal process can be developed to address concerns |

| Changes to amend the payment, penalty and debt rules for child support | |||||

| 12. Automatic deduction of child support from salary and wages | Ensures that all amounts of child support owed by employees are made on time, resulting in more receiving parents receiving child support | Some employees may have privacy concerns May result in a compliance cost for some employers |

Not applicable | Yes | Recommended, as benefits considered to outweigh costs |

| 13. A “pass-on” system | May increase the incentive to pay child support | Would involve significant cost or, alternatively, would create uncertainty or hardship where pass-on payments not paid | Not applicable | Yes, in some circumstances | Not recommended to meet these objectives |

| 14a. A two-stage initial late payment penalty | Does not unduly punish non-payment due to an short term oversight Encourages positive behaviour Better mirrors treatment for tax debts |

Not applicable | Yes | Recommended | |

| 14b. Reduce incremental penalty rate | Would prevent such rapid escalation of child support penalty levels Would increase incentives to pay |

Not applicable | Yes | Recommended | |

| 15a. Cap penalty levels | Would prevent such rapid escalation of child support penalty levels | Once cap reached, there would be no more financial incentives to comply | Not applicable | No | Not recommended |

| 15b. Aligning child support penalties with tax penalties and interest | Would provide efficiencies for Inland Revenue | Not easily achieved given fundamental differences between the two systems | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not recommended |

| 16a. Relax penalty write off rules | Would help to facilitate payment of assessed child support debt when paying parents agrees to enter into an instalment arrangement or is in significant hardship | Not applicable | Yes | Recommended | |

| 16b. Automatically write-off low levels of penalty-only debt | Would allow Inland Revenue to focus more on assessed debt rather than low levels of penalty only debt where the chances of collection are very low | Not applicable | Not applicable | Recommended | |

| 17. Write-off assessed debt owed to the Crown that cannot be paid due to serious hardship | Greater consistency, as receiving parents can waive equivalent debts Better mirrors treatment of tax debts |

Not applicable | Not applicable | Recommended, but not for debt owed to receiving parents | |

| 18a. A child support debt amnesty | Would reduce current debt arrears | Rewards non-compliance and creates inequity compared to complying parents. May create future disincentive to comply |

Not applicable | No | Not recommended |

| 18b. Passing on penalties received to receiving parents | Compensates receiving parents for loss of funds | Inconsistent treatment between receiving parents Complex to administer Fiscal implications |

Not applicable | Unlikely in most cases | Not recommended |

Key changes to update the child support formula

37. While any change in the child support formula could have a material impact for a minority of parents, the overall objective of any change should be to achieve a fairer outcome that encourages more parents to pay their outstanding child support liabilities voluntarily. The following options in relation to the child support formula were considered with this in mind.

Option 1: Recognising up-to-date estimates on the expenditure for raising children (recommended with options 2 and 3)

38. The first option considered is for the child support formula to better recognise actual and up-to-date estimates on the expenditure for raising children in New Zealand.

39. Until recently, there was little specific New Zealand research on estimated expenditures for raising children in New Zealand. Research on this subject was therefore conducted in 2009 by Inland Revenue officials.[3] This research followed equivalent Australian studies on the cost of raising children as far as possible, but with New Zealand data.

40. These up-to-date estimates of expenditure for raising children in New Zealand show that child support payments under a revised child support formula would increase in line with parental income. This reflects the fact that parents with higher incomes generally spend more on their children, with the amount increasing with family income but declining as a proportion of income. To recognise this decline, and to not discourage parents from earning extra income, the discussion document recommended that, if this option was adopted, an income cap should be retained. Income above the cap would not be recognised for child support purposes.

41. The research also showed that expenditure for raising children rises with the age of the children, with teenagers costing more than younger children. Also, due to economies of scale, each additional child generally costs less than the last. The discussion document recommended that these factors be taken into account were this option adopted.

42. Results of the online consultation indicated that:

- 54 percent of respondents thought that child support payments should vary depending on the income of the parents, whereas the other 46 percent thought that it should be based on a fixed estimate of how much expenditure is needed to raise a child in any situation.

- 58 percent thought that child support payments should be higher for teenagers than for children under 13.

- 60 percent thought that there should be an income cap for the purposes of calculating child support payments.

Option 2: Reducing the current shared-care threshold (recommended with options 1 and 3)

43. Changes to patterns of parenting have occurred since the Child Support Act was introduced and it is now more common for both parents to be actively involved in raising their children.

44. The current child support scheme can, in some cases, provide disincentives to parents sharing the care of their children. The scheme does not recognise the significant expenditures some parents incur while trying to retain a significant role in their children’s upbringing. This may affect the paying parent’s willingness or ability to meet their child support obligations or to maintain any significant level of care.

45. When both parents have regular care of their children, expenditures for the paying parent increase with an associated (but disproportionately lower) reduction in the receiving parent’s expenditures. This is because of a loss of the economies of scale that exist in two-parent families.

46. If the child support scheme is to recognise greater levels of shared care a key question to be addressed is whether the expenditures incurred by both parents need to be borne in a more equitable way.

47. A greater level of recognition could be given to lower levels of shared and regular care being provided by paying parents, by lowering the current shared-care threshold of 40 percent of nights. One of the main criticisms in this area is that this test for recognising shared care is too high and also creates a “cliff” effect. A “cliff” effect means that there can be a substantial change in the amount of child support payable, depending on whether or not shared care is established at the prescribed level.

48. Sixty nine percent of the respondents to the online consultation thought that the current 40 percent for shared care should be lowered to include other levels of regular care.

49. Various levels of care have been considered by officials. One option is to recognise, on a tiered basis, care in excess of 28 percent of annual care (on average two nights a week). This would provide recognition to those paying parents who provide high levels of care, but who are unable to satisfy the current 40 percent threshold.

50. If the tiered approach from 28 percent of care was adopted, it could be based on Table 1:

| Number of nights of care annually | Proportion of net expenditure for child considered incurred |

|---|---|

| 0 to 103 (0% to less than 28%) |

Nil |

| 104 to 126 (28% to less than 35%) |

24% |

| 127 to 175 (35% to less than 48%) |

25% plus 0.5% for each night over 127 nights |

| 176 to 182 (48% to 50%) |

50% |

51. Alternatively, care could be recognised, again on a tiered basis, where it is in excess of 14 percent of annual care (on average one night a week). This is the threshold adopted in some other jurisdictions (for example, in Australia and Britain). Although this option would provide recognition to more paying parents who care for their children, it may be seen as too generous, particularly when the majority of everyday and other significant one-off costs are still being borne by receiving parents. It would also involve a greater fiscal cost as more child support liabilities would be reduced, thereby further reducing the amount received by the Government to offset benefit payments to receiving parents.

52. Under either of these tiered approaches, paying parents would have the care they provide acknowledged at a given rate, with higher levels of care reflected in a corresponding adjustment in the child support liability according to their income levels. This would recognise the additional expenditures incurred.

53. One of the main advantages of a tiered approach is that once shared care is confirmed, subsequent small increases in levels of care would not give rise to major changes in child support for either parent. There would be less of a cliff effect, with a series of smaller incremental adjustments instead.

54. Another alternative is to have a single, but lower, single shared-care threshold. This would maintain the simplicity of the current shared-care rules and would allow more paying parents to benefit from the shared-care rules, thus recognising their contributions towards raising their children. Regardless, wherever such a threshold level would be set, it would be seen as arbitrary and still create a noticeable cliff effect.

Option 3: Taking both parents’ income into account (recommended with options 1 and 2)

55. Taking the income of both parents into account when determining levels of child support payment better reflects the realities of modern-day parenting and parents’ relative abilities to contribute towards the expenditure for raising their children. It assumes that both parents should be financially responsible for raising their child.

56. Under this option, expenditures for raising children would be worked out based on the parents’ combined income, with the expenditure distributed between parents in accordance with their respective shares of that combined income and their level of care of the child. This option is linked with option 2.

57. The main advantages of an income-shares approach are:

- It is transparent. It provides an estimate of how much is being contributed by each parent towards the support of their children.

- It better reflects parents’ relative abilities to financially contribute towards raising their children and parallels likely expenditure by those parents as if they were in a two-parent household in which both parents have income.

- It makes processes relating to changes of financial circumstances clearer and simpler. If there is a reduction in the income of either parent, this can be automatically reflected in the contribution calculation, potentially removing the need for an administrative review.

58. Disadvantages of the income-shares approach are:

- If the receiving parent’s income varies significantly – for example, to accommodate the needs of children to be cared for – there is potential to increase conflict between parents, as the paying parent’s child support contribution would also vary.

- The approach could make the level of payments less secure, as a change in either parent’s income may result in a change in child support payable or receivable.

59. However, these disadvantages need to be balanced against the reality that changes in either parent’s work patterns do affect their children and would do so if the parents were living together. Ideally, any formula adopted should reflect this reality.

60. On balance, the advantages of the income-shares approach seem to outweigh the possible disadvantages.

61. Work incentives seem to be neither advantaged nor disadvantaged overall from taking both incomes into account. Some receiving parents could be discouraged from participating in the workforce because a portion of every dollar they earned over the self-support amount would be “lost” through a decrease in the child support they received. On the other hand, there may be a greater incentive for paying parents to earn higher incomes if they were paying less in child support as a result of both incomes being taken into account.

62. Sixty eight percent of the respondents to the online consultation felt that the income of both parents should always be included in working out the amount of child support payable.

63. Whether the income of a new partner should be taken into account when calculating child support liabilities has also been considered. Officials’ view is that such income should not be automatically included, since the nature of a formula is that it cannot reflect what a new partner’s involvement (financially or otherwise) will be in a child’s life. In some cases a new partner effectively becomes a new parent, while in others that is not the case. The administrative review process is available where a parent considers that the income of a new partner should be taken into account.

Option 4: Introducing a revised child support formula, taking options 1–3 into account (recommended option)

64. Although options 1–3 can be considered in isolation, it would be preferable to have all of these three elements taken into account when considering wider changes to the child support formula. Doing so would result in a comprehensive change to the formula, incorporating:

- basing child support payments on estimated average expenditures for raising children in New Zealand;

- recognising lower levels of care; and

- taking the income of both parents into account.

65. The alternative options of only incorporating one or two of these options would limit the overall impact and effectiveness of any change. They would represent a less comprehensive and less transparent solution.

66. Sixty nine percent of the respondents to the online consultation thought that all these factors should be used to work out child support payments. Most written submissions also indicated a preference for comprehensive change rather than change in just one area.

67. A comprehensive new formula could have the following characteristics:

- It would incorporate lower levels of shared care (for example, by way of tiered thresholds from 28 percent of nights) to deal with concerns about insufficient recognition of regular and shared care of children.

- To deal with concerns about the capacity to pay, both parents’ incomes would be included in the formula, with payments being apportioned according to each parent’s share of total income. Where there were other dependent children, a parent’s income would be reduced for the assumed expenditure for those children, before calculating their child support contribution.

- The formula would use a new scale of income percentages that reflected up-to-date information on the net (of average tax benefits) expenditures for raising children in New Zealand. These percentages would vary with:

- the number of children;

- the age of the children (the percentage would be higher for children over 12 years); and

- the combined income of the parents.

68. Table 2 sets out how the expenditures for raising children calculation would look for the purposes of the revised formula. The expenditures used would be adjusted each year to keep up to date with average earnings.

| Parents’ combined child support income (income above the living allowance amounts)[1] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of children | $0 – $24,081[2] |

$24,082 – $48,162[3] |

$48,163 – $72,243[4] |

$72,244 – $96,324[5] |

$96,325 – $120,405[6] |

Over $120,4056[6] |

| Expenditure for raising children (to be apportioned between the parents) | ||||||

| Children aged 0–12 years | ||||||

| 1 child | 17c for each $1 |

$4,094 plus 15c for each $1 over $24,081 |

$7,706 plus 12c for each $1 over $48,162 |

$10,596 plus 10c for each $1 over $72,243 |

$13,004 plus 7c for each $1 over $96,324 |

$14,689 |

| 2 children | 24c for each $1 | $5,779 plus 23c for each $1 over $24,081 |

$11,318 plus 20c for each $1 over $48,162 |

$16,134 plus 18c for each $1 over $72,243 |

$20,469 plus 10c for each $1 over $96,324 |

$22,877 |

| 3+ children | 27c for each $1 | $6,502 plus 26c for each $1 over $24,081 |

$12,763 plus 25c for each $1 over $48,162 |

$18,783 plus 24c for each $1 over $72,243 |

$24,563 plus 18c for each $1 over $96,324 |

$28,897 |

| Children aged 13+ years | ||||||

| 1 child | 23c for each $1 | $5,539 plus 22c for each $1 over $24,081 |

$10,836 plus 12c for each $1 over $48,162 |

$13,726 plus 10c for each $1 over $72,243 |

$16,134 plus 9c for each $1 over $96,324 |

$18,302 |

| 2 children | 29c for each $1 | $6,983 plus 28c for each $1 over $24,081 |

$13,726 plus 25c for each $1 over $48,162 |

$19,746 plus 20c for each $1 over $72,243 |

$24,563 plus 13c for each $1 over $96,324 |

$27,693 |

| 3+ children | 32c for each $1 | $7,706 plus 31c for each $1 over $24,081 |

$15,171 plus 30c for each $1 over $48,162 |

$22,395 plus 29c for each $1 over $72,243 |

$29,379 plus 20c for each $1 over $96,324 |

$34,195 |

| Children of mixed age* | ||||||

| 2 children | 26.5c for each $1 | $6,381 plus 25.5c for each $1 over $24,081 |

$12,522 plus 22.5c for each $1 over $48,162 |

$17,940 plus 19c for each $1 over $72,243 |

$22,515 plus 11.5c for each $1 over $96,324 |

$25,285 |

| 3+ children | 29.5c for each $1 | $7,104 plus 28.5c for each $1 over $24,081 |

$13,967 plus 27.5c for each $1 over $48,162 |

$20,589 plus 26.5c for each $1 over $72,243 |

$26,971 plus 19c for each $1 over $96,324 |

$31,546 |

1 Calculated by adding the two parents’ child support incomes, that is, adding each parent’s adjusted taxable income minus their living allowance of $16,054 (1/3 of Average Weekly Earnings (AWE)).

2 .5 of AWE.

3 AWE.

4 1.5 times AWE.

5 2 times AWE.

6 2.5 times AWE. Expenditure for raising children does not increase above this cap. Note that this equates to a cap at a combined adjusted taxable income of $152,514.

* The rates are the average of the two previous age categories.

How this approach would work in practice

69. Under a new formula, each parent would be allocated a standard living allowance that would be deducted from his or her respective taxable income. If the net amount was negative, the taxable income would be treated as zero.

70. The two net amounts would be combined and each amount expressed as a percentage of this total. These proportions would then be applied to the expenditure relevant for that child so that the expenditure for raising the child or children would be split between the two parents based on their relative net incomes.

71. Each parent’s percentage of shared care would then be deducted from the result to produce a net liability for one of the parents. This would be the parent whose shared-care percentage is less than his or her share of total net income.

72. To recognise the care a parent provides for other dependent children, an amount (in addition to the living allowance) would be deducted from the parent’s adjusted taxable income before applying the basic formula. This amount would be calculated in the same way as the calculation described above. In this way other dependant children would be treated the same way as children subject to child support.

Summary impacts and recommendations

73. There are wide-ranging views about what a fairer and more effective scheme might look like and how to achieve this, and it will never be possible to design rules to satisfy all concerned. There are too many conflicting interests and points of view. Officials consider, however, that this option provides the best opportunity of introducing a revised formula that represents a fair reflection of the expenditure for raising children, the parents’ contribution to care and the parents’ capacity to pay. This, in turn, should better encourage parents to pay their child support and therefore improve the well-being of their children. For these reasons the proposed child support formula is considered a significant improvement over the current one.

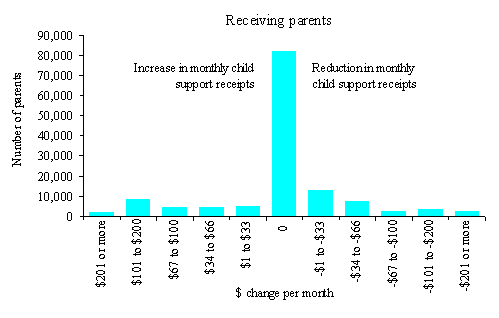

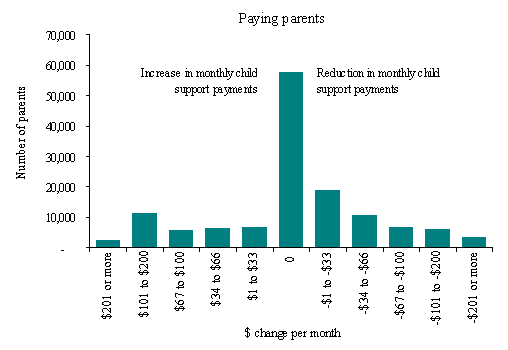

74. These changes to the child support formula would have financial implications for parents. Tables 3A and 3B show the estimated affects on parents. Overall, it is estimated that 70,502 parents would be better off under the changes (that is, they will receive more or pay less child support) and 62,467 worse off (that is, they will receive less or pay more).

75. For the majority of parents whose child support will be affected, the change in child support received and paid is likely to be between plus or minus $66 per month (plus or minus $800 per year).

76. For a large percentage of receiving and paying parents (60 percent and 40 percent respectively), the changes to the formula would not result in any change in the amounts received or paid. For 140,053 parents, there would be no change. This is because many parents would continue to either receive a sole-parent benefit (and therefore not receive child support payments directly) or continue to pay the minimum contribution because their income level is below the minimum level for child support purposes. For those who would be affected, however, the resulting change would represent a more transparent and equitable result in a greater number of different circumstances.

77. Over 82 percent of current child support received and about 74 percent of child support paid would therefore either be unaffected or affected to the extent of plus or minus $66 per month (plus or minus $800 per year).

78. Parents who would qualify for the wider recognition of shared care would be most affected, with paying parents likely to pay less in such cases. Consequently, the means by and extent to which regular care is recognised is important to the overall outcome for both parents. If shared care were recognised at 28 percent, there would be nearly as many receiving parents who would receive more (24,505 parents) as receiving parents who would receive less (29,776 parents). For paying parents, 32,691 parents would pay more and 45,997 less.

79. These impacts will in some cases be reduced, as changes in the amount of child support received or paid affects the amount of Working for Families tax credits received.

Table 3A: Monthly change in child support receipts

Table 3B: Monthly change in child support payments

80. The approach taken to the review process was to categorise the parents into ‘paying parents’ and ‘receiving parents’ – being a ‘receiving parent’ is generally indicative of being the primary caregiver, and this can be the mother, the father, or another person. That said, as the majority (but certainly not all) of receiving parents are female, women are more likely to be adversely affected by this change.

81. Taking both female paying and female receiving parents into account, it is projected that 25,954 of these parents would receive more or pay less child support and 31,428 of these parents would receive less or pay more child support. The majority (83,039) would be unaffected.

82. Female parents who would be affected by the changes and who have taxable incomes of less than $20,000 may both receive more/pay less or receive less/pay more child support. About half of all female parents who would receive less or pay more have taxable incomes of $20,000 or less. Likewise, about half of the female parents who would receive more or pay less also have taxable incomes of $20,000 or less. Many of these parents will also receive non taxable Working for Families tax credits, and many may be partnered.

83. As their position is not affected by the changes, receiving parents who remain on a sole parent benefit would continue to receive full benefit levels.

84. Taking both male paying and male receiving parents into account, it is projected that 44,307 of these parents would receive more or pay less child support and 30,750 of these parents would receive less or pay more child support. 56,191 would be unaffected by the proposed formula.

85. About half of all males who would pay more or receive less would have taxable incomes of lower than $40,000. On the other hand, nearly 65 percent of the males who would pay less or receive more child support have taxable incomes of $40,000 or less.

Fiscal implications

86. The fiscal implications (including administrative costs) of introducing a comprehensive new child support formula, recognising shared care at 28 percent, are as follows:

| Costs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011/12 ($m) |

2012/13 ($m) |

2013/14 ($m) |

2014/15 ($m) |

2015/16 & outyears ($m) |

|

| Child support | |||||

| - Administrative costs in implementing new formula | 2.887 | 10.417 | 6.758 | 2.906 | 1.837 |

| - Revenue costs (formula change including reducing shared care to 28%**) | – | 0.500 | 2.250 | 3.750 | 6.000 |

** This assumes an additional 10% of parents would qualify for shared care (currently only about 5% of parental relationships qualify). It is estimated that the number of parents who qualify would increase from approximately 7,000 to 20,000.

Secondary changes to update the child support scheme more generally

87. Although the following options for change to the child support scheme more generally are separate from the child support formula itself, they nevertheless affect the ability to claim child support and/or the amount of child support payable or receivable.

Measuring and recognising shared care

Option 5: Recognising shared care using a test other than “number of nights” (partially recommended)

88. Whether parents have shared care for child support purposes is generally determined by the number of nights of care the parents each provide. However, this test does not necessarily produce the correct outcome, as there are occasions when very significant (and costly) daytime care is provided by paying parents. Consideration was therefore given to establishing whether another test (for example, based on days or time in general) could be used for determining shared care.

89. It is considered, however, that the number of nights that a child spends with a parent is still the best and easiest method of establishing care levels in the first instance. Overnight care invariably necessitates the provision of accommodation, travel and food. Also, it is generally easy to establish how many nights a child spends with a parent. The administrative review process can still, however, provide departures from this test on a case-by-case basis if the costs of daytime contact are significant.

90. Consideration has also been given to providing departures by way of a Commissioner discretion. A Commissioner discretion would result in a process that was potentially simpler and more straightforward than the current administration review process for cases in which the costs of daytime contact are significant.

Option 6: Relying on parenting orders and agreements (recommended)

91. An option mooted in the discussion document was that Inland Revenue should be able to rely on a parenting order or agreement to establish the number of nights a child spends with each parent for child support purposes. This would result in more efficient processing of shared-care applications. It would also reinforce what the courts have determined to be in the best interests of the children. This initiative would extend to parenting agreements which, while not enforceable by the courts, nonetheless convey the intentions and expectations of both parents.

92. If this option were to be adopted, parents should be able to rebut a presumption made on the basis of a parenting order or agreement when it could be shown that the order or agreement was not being followed in practice. A new administrative review ground and Commissioner discretion would be required for this purpose. The onus of proving that the order or agreement was not being adhered to would rest with the parent making the challenge.

Defining income and measuring payment levels

Option 7: Changing the definition of income for child support purposes (recommended)

93. “Income” for child support purposes should, in general, continue to be defined as taxable income. However, important changes have been made to the way that income is defined for the purposes of Working for Families tax credits, and these changes should be considered for child support purposes.

94. In particular, from 1 April 2011, losses, including losses from rental properties, are added back so that these losses cannot be used to reduce income when assessing eligibility for Working for Families tax credits. Making a similar change for child support purposes, on the basis that this would better reflect the real income that families would normally have available to them, has been considered. Likewise, ensuring that trustee income is counted as part of a family’s total income has been considered in the child support context.

95. Such rules were implemented to counter families structuring their affairs to inflate entitlements to social assistance (or reduce liabilities). These rules would also help maintain the child support scheme’s integrity.

Option 8: Recognising re-establishment costs (recommended)

96. A paying or receiving parent will frequently take on additional employment or overtime to help re-establish themselves after a separation – for example, to buy an alternative family home. Currently, income from secondary employment and overtime is automatically included in the formula calculation.

97. Trying to incorporate recognition of all re-establishment costs into the child support formula would not be appropriate. Instead, re-establishment costs, for a period of three years after a relationship separation, could become a ground for an administrative review. This could be subject to a parent (either receiving or paying) meeting requirements that the income that was used to pay for the re-establishment costs was earned in accordance with a pattern that was established after the parents first separated and that any excluded income in respect of the re-establishment costs is no more than 30 percent of taxable income.

98. In the online consultation, 71 percent of the respondents were in favour of such a change. Most written comments were also supportive.

Option 9: Allowing prescribed payments (recommended)

99. A further option is to provide the Commissioner with the discretion to allow certain payments to count towards a paying parent’s child support liability. Currently, payments made by a paying parent are not credited against their child support liability. Introducing the ability to do so is likely to provide a greater incentive to pay child support, as a paying parent may be more comfortable that the payment (or at least part of it) is directly benefiting the child according to the paying parent’s desires for the child’s upbringing.

100. For a payment to be recognised, however, it would ideally need to have both parents’ agreement, as parents’ views about expenditure choices may differ. Alternatively, it would need to be of a prescribed type – for example, childcare costs for the relevant child; fees charged by a school or preschool for that child; amounts payable for uniforms and books prescribed by a school or preschool for that child; or fees for essential medical and dental services for that child.

101. Credit could be given up to a maximum of 30 percent of the ongoing liability, provided the balance of child support is paid as it becomes due. This facility should not, however, be available to parents whose child support liability has been adjusted to reflect shared care. Nor should it be available if the receiving parent receives a sole-parent benefit only, as the Government is already in effect providing contributions towards these payments as part of that benefit.

102. In the online consultation, 81 percent of the respondents were in favour of such a change. Most written comments were also supportive.

Determining eligibility

Option 10: Reducing the qualifying age of children (recommended)

103. Currently, child support is normally payable until a child reaches the age of 19 years. However, many children start higher education before this age (or are able to work or claim a benefit in their own right) and so have access to the student loan and student allowance schemes.

104. It is therefore recommended that the qualifying age should be changed so that child support payments automatically end when the child reaches 18 unless the child is still in full-time secondary education. In that case, the child would cease to be a qualifying child when they left school.

105. In the online consultation, 76 percent of the respondents were in favour of this change.

Option 11: Determining who can claim child support (not recommended)

106. Currently, a person can claim child support if he or she is the sole or principal provider of care for a child (or shares that role equally with someone else). There are no other specific requirements or tests that must be satisfied.

107. We have considered introducing restrictions on who is able to claim child support. The ability to claim child support could be restricted to:

- a parent of a child; or

- someone who has legal custody of a child; or

- someone who is entitled to receive a Government benefit for a child.

108. This could address the rare occasions when child support could be considered to be claimed inappropriately (in particular, when teenage children have left home of their own accord to live with an adult other than a parent). However, difficulties could arise if this test were adopted. In particular, if wider family members are caring for a child, it makes sense that they should be able to claim child support regardless of whether they fall into one of the above categories. Safety, care and protection concerns may dictate that a child should not live with his or her parents. This needs to be balanced with the responsibility of parents to stay involved in decisions regarding where their teenage children live (and the financial obligations that flow from this).

109. Inland Revenue, being predominantly a collection agency, is not best placed to make judgements that determine who a child should be living with. It would therefore be preferable for Inland Revenue officials to discuss with the Ministry of Social Development and the Ministry of Justice whether an appeal process should be developed whereby parents can challenge, in the Family Court, a child support claim made by another person in the Family Court.

Changes to amend the payment, penalty and debt rules for child support

110. Ensuring that child support payments are delivered on time and that payment arrears are dealt with by Inland Revenue as effectively as possible is critical. The following options were considered in order to establish ways to better encourage and facilitate parents to make timely child support payments for the benefit of their children.

Making payments of child support

Option 12: Automatically deducting child support payments from salary and wages (recommended)

111. In order to ensure that as many payments as possible are made, and made on time, an option is to make it compulsory for all child support payments to be automatically deducted from the employment income of paying parents. Paying parents would therefore have their payments automatically co-ordinated with their pay periods, whether those periods were weekly, fortnightly or monthly.

112. It is recognised that some paying parents have concerns about their employers knowing that they are making child support contributions. However, the public interest in operating an effective child support scheme should arguably outweigh these individual concerns.

113. There may be some, albeit marginal, increased compliance costs for employers from having to make deductions and record and pay the money to Inland Revenue through the PAYE system. The increase in the number of deductions would, however, be small relative to the volumes already being processed at the same time to account for PAYE, ACC and KiwiSaver contributions (and for child support payments that are already being deducted by employers when a default occurs).

114. In the online consultation, 66 percent of the respondents were in favour of this change.

Option 13: Passing on child support payments to receiving parents (not recommended)

115. Government-provided welfare benefits give certainty to sole parents about the amount that they will receive to assist them in raising their children. However, some paying parents maintain that they have little incentive to pay child support if their payments are retained by the Crown up to the amount of the benefit paid. The children are no better off as a result of the child support payment, because the benefit is paid regardless.

116. “Pass-on” means that, instead of being retained by the Crown, child support payments are passed on to the beneficiary receiving parent. This may increase the incentive to pay child support and improve compliance. It may also provide a greater incentive for receiving parents who are beneficiaries to trace paying parents and to contest the level of contribution if this is considered inadequate or unjust.

117. However, pass-on would involve a very significant fiscal loss to the Government, and this would be reduced only if benefits were wholly or partly offset against benefit payments. Offsetting benefit payments would create uncertainty, and in some cases hardship, for beneficiaries and the children involved, as the overall amount they received would be dependent on whether and how promptly the other parent paid his or her child support contribution.

118. Also, pass-on does not ensure that child support payments are applied for the benefit of the child, which would be important in increasing any incentives to pay.

119. Some countries that have pass-on have used it to emphasise the welfare of the children when child poverty has been the central concern, and also when child support payment rates have been of concern. However, New Zealand’s child support collection rate for assessed child support compares well with other countries, lessening the incentive to introduce pass-on without strong evidence to support such a change.

Incentivising payments

Option 14: Reducing child support penalty rates (recommended)

120. Currently, paying parents who fail to pay in full and on time incur an initial penalty of 10 percent of the unpaid amount. A further penalty of 2 percent of the unpaid amount is imposed on a compounding basis for each month that the amount remains outstanding.

121. Penalties play an important role in encouraging parents to meet their child support obligations. If they are excessive, however, they can discourage the payment of child support to the detriment of the children concerned. Child support debt, as at 30 June 2011, stands at $2,271m. This figure is made up of child support assessments of $605m and associated penalties of $1,656m.

122. These figures show the magnitude of the problem. Various options have therefore been considered in relation to changing child support penalty rates.

123. In respect of initial penalties, a 10 percent penalty for any late payment may be seen as excessive if the payment was late only because of an oversight.

124. An option therefore is to implement a two-stage initial penalty whereby a paying parent is charged 2 percent if the payment is not made on time but is only charged the remaining 8 percent if the amount remains unpaid after 7 days. This gives the paying parent a week to make any payments inadvertently not made, therefore encouraging positive behaviour and decreasing the level of unpaid debt. This approach also better mirrors the two-stage treatment adopted for the initial late payment of tax debts.

125. The cumulative nature of the 2 percent incremental penalty means that penalty amounts can grow rapidly, often vastly outstripping the original debt. At some point, parents who would otherwise be willing to pay off their assessed liability may become reluctant to approach Inland Revenue to do so. The high penalty levels could be acting as a disincentive to compliance.

126. Reducing the incremental penalty from 2 percent would help prevent the current rapid rate of escalation for penalty debt, and it would stop the debt reaching levels that paying parents feel are disproportionate to the original debt. A lower monthly penalty rate is therefore recommended.

127. A reduction of the incremental monthly penalty from 2 percent to 1 percent after a year of non-compliance by the paying parent would reduce these disincentives.

128. If the incremental monthly penalty rate is reduced from 2 percent to 1 percent after one year’s non-compliance, other offsetting enforcement measures should be implemented. This would see paying parents being subject to more intensive case management from Inland Revenue.

129. In the online consultation, 65 percent of the respondents were in favour of making this change.

Option 15: Other penalty options considered (not recommended)

130. Some of the other penalty options considered, but not recommended by officials, include:

- Capping the amount of penalties that could apply to a parent’s child support debt. This would stop debt accumulating and may reduce the reluctance that some parents have in contacting Inland Revenue. However, once the cap was reached, there would be limited further incentive for paying parents to continue to pay their child support liability.

- Aligning child support penalties to tax penalties and use-of-money interest. Although this could provide administrative efficiencies for Inland Revenue, there are many differences between the two systems that mean that tax penalties and interest are not fully relevant to child support (for example, child support is fundamentally collected on behalf of the receiving parent, not the Crown).

Option 16: Amending penalty write-off rules (recommended)

131. Although the primary objective of any changes to the penalty rules should be to progressively recover any existing assessed debt and establish the regular payment of child support liabilities, writing off penalties in certain circumstances may help facilitate regular payment or, alternatively, be justifiable on hardship grounds.

132. Some options considered in this regard include:

- relaxing the circumstances in which penalties can be written off, including when a paying parent agrees and adheres to an instalment arrangement for ongoing compliance;

- allowing Inland Revenue to automatically write off low levels of penalty-only debt below a certain value (to be determined periodically by Inland Revenue).

133. The starting position for writing off penalties should ideally be that a paying parent who comes to Inland Revenue to arrange the payment of a debt is trying to comply. On that basis, one option considered is that if an agreed amount is to be written off, it should be written off at the start of an instalment arrangement (rather than after a significant period of positive compliance, as is currently the case).

134. This option would relax the circumstances in which penalties can be written off for ongoing compliance, as all that would be required would be an agreed instalment arrangement. If the paying parent defaults again, new late-payment penalties could be applied. Written-off debt should ideally not be reinstated unless, for example, the write-off is based on false or misleading information provided by the paying parent.

135. To avoid deliberate exploitation of such write-off rules, Inland Revenue could be able to decline to enter into an instalment arrangement when a paying parent has not complied with a previous arrangement and there has been no due cause for this non-compliance.

136. Another connected option is to allow Inland Revenue a wider range of options to negotiate the write-off of penalties if the paying parent would be placed in significant hardship or if it would be a demonstrably inefficient use of Inland Revenue’s resources to collect the debt because the chances of collection are very low. To ensure transparency and consistency, such a provision would be supported by published administrative guidelines or criteria.

137. An additional option is to allow Inland Revenue to automatically write off low levels of penalty-only debt (when assessed debt has been paid and only penalty debt remains). This discretion would allow Inland Revenue, once all assessed child support debt has been paid, to automatically write off all penalty-only debt below a certain value (to be determined by Inland Revenue on the basis of set published criteria and guidelines)

138. In the online consultation, 55 percent of the respondents were in favour of relaxing the ability to write off child support debt in certain circumstances.

Option 17: Allowing certain assessed child support debt to be written off (recommended)

139. Inland Revenue cannot currently write off assessed debt because, in many cases, the debt is owed to the receiving parent for the care of the child. When a receiving parent is not on a sole-parent benefit, however, that parent can instruct Inland Revenue to waive the assessed debt.

140. Inland Revenue does not have an equivalent discretion to waive assessed debt owed to the Crown when a parent receives a sole-parent benefit. The courts can order a debt to be written off, but this is costly and time-consuming.

141. An option considered is to allow assessed debt relating to beneficiaries to be written off by Inland Revenue on serious hardship grounds. Similar allowance already exists in relation to tax debt – for example, when someone has a serious illness and is unable to work, or is otherwise unable to meet minimum living standards.

Option 18: Other penalty write-off options considered (not recommended)

142. Some of the other penalty write-off options considered, but not recommended by officials, include:

- Introducing a child support debt amnesty whereby if all existing assessed debt was paid off during prescribed period, all associated penalties would be automatically written off. Although this would result in recovery of arrears, it would not be likely to change the long-term behaviour of errant paying parents. It would also see persistent failure to comply being rewarded, which would send the wrong message about the fairness of the child support scheme more generally.

- Passing on penalty payments received to the receiving parent. If this option were adopted, receiving parents would be compensated for their loss of funds. However, passing on penalties would be complex to administer and would also create inconsistencies in the treatment of different receiving parents. It is uncertain whether this measure would act as an additional incentive for paying parents to comply.

Estimated fiscal costs of changes to the payment, penalty and debt rules for child support

143. The recommended changes to the child support payment, penalty and debt rules noted above are estimated to have a fiscal cost of around $10 million per annum. This estimate takes into account the fact that, although child support penalties are included in the Government’s accounts as income, those accounts also include a provision for writing off 97 percent of the amount of that income.

144. The fiscal implications over the forecast period are as follows:

| Cost | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011/12 ($m) |

2012/13 ($m) |

2013/14 ($m) |

2014/15 ($m) |

2015/16 & outyears ($m) |

|

| Child support | |||||

| - Administrative costs (included in formula changes) | – | – | – | – | – |

| - Revenue (incl. reducing penalty rates) | – | – | 2.500 | 10.000 | 10.000 |

145. The options that are designed to increase compliance would, however, also create additional cash flows and a reduction in future expenses to the Crown, and would help defray some of this fiscal cost. Although not included above (as improved compliance is difficult to predict and measure), it is estimated that a 1 percent increase in the amount of child support paid to the Crown would have a positive fiscal impact of around $2 million per annum. Lower penalty rates would also slow down the accumulation of child support debt.

CONSULTATION

146. As noted previously, a significant level of public consultation has been undertaken on the options for potential child support reform.

147. There has also been consultation with a range of Government agencies on child support issues over a period of time. This consultation was with the Ministry of Social Development, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, the Treasury and the Families Commission. Feedback from these agencies has, wherever possible, been incorporated into the formulation of the policy options discussed here. There is a general recognition from these agencies that the various issues with the child support scheme need to be addressed.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

148. It is recommended that the child support formula be amended to better recognise shared care and to take account of the income of both parents and the expenditure for raising children in New Zealand (option 4). Doing so would provide more equitable financial support for children in a variety of circumstances. It would also better reflect many of the social and legal changes that have occurred since the introduction of the current scheme in 1992, in particular the greater emphasis on separated parents sharing the care of and financial responsibility for their children.

149. We also recommend:

- changes to the operation of the formula to update the child support scheme more generally (Options 5a, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10); and

- changes to the rules relating to the payment of child support, the imposition of penalties, and the writing-off of penalties and debt to better encourage and facilitate parents to make timely child support payments for the benefit of their children (Options 12, 14a, 14b, 16a, 16b, 17).

150. The total fiscal impact of all the recommended proposals, together with associated administration costs for their implementation, is:

| Cost | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011/12 ($m) |

2012/13 ($m) |

2013/14 ($m) |

2014/15 ($m) |

2015/16 & outyears ($m) |

|

| Revenue costs of introducing proposed new child support formula | – | 0.500 | 2.250 | 3.750 | 6.000 |

| Revenue costs of proposed changes to the payment, penalty and write-off rules | – | – | 2.500 | 10.000 | 10.000 |

| Total Inland Revenue administrative costs in implementing proposals | 2.887 | 10.417 | 6.758 | 2.906 | 1.837 |

| Total | 2.887 | 10.917 | 11.508 | 16.656 | 17.837 |

IMPLEMENTATION

151. Significant changes to the child support scheme would require amendments to the Child Support Act 1991 and to any consequential provisions in other legislation. These amendments would be included in a Child Support Amendment Bill 2011, planned for introduction in September 2011.

Implementation dates

152. To allow for the required significant changes to Inland Revenue’s systems and processes, the earliest possible implementation date for changes to the child support formula is 1 April 2013. Changes relating to the payment, penalty and debt rules, and other changes to the scheme, would be introduced on 1 April 2014.

153. Various implementation risks have been identified with introducing significant child support formula changes by 1 April 2013. Given existing systems constraints, Inland Revenue is not able to make the necessary changes required through its computer system (FIRST) by this date.

154. As a temporary measure for the period from 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2014, therefore, an existing information technology product owned by Inland Revenue would be used to automate the calculation of child support assessments under the new formula. This would occur outside of FIRST. Data would be drawn from FIRST, and then revised information would be uploaded back into the FIRST system for the updating and issuing of the annual assessment. A more manual option would be available for ad hoc calculations or situations in which information is not available within FIRST.

155. The process would be developed as a temporary measure while the necessary changes and testing were made to the FIRST system for full integration by 1 April 2014.

156. Inland Revenue considers that there are some risks associated with this solution, but they are manageable.

MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

157. In general, Inland Revenue monitoring, evaluation and review of any child support changes would take place under the generic tax policy process (GTPP). The GTPP is a multi-stage policy process that has been used to design tax policy (and subsequently social policy administered by Inland Revenue) in New Zealand since 1995.

158. The final step in the process is the implementation and review stage, which involves post-implementation review of legislation and the identification of remedial issues. Opportunities for external consultation are built into this stage. In practice, any changes identified as necessary following repeal would be added to the tax policy work programme, and proposals would go through the GTPP.

1 http://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/publications/2010/2010-dd-supporting-children

2 http://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/publications/2011/2011-other-supporting-children-feedback-summary

3 http://nzae.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Costs_of_raising_children_NZAE_paper_v2.pdf