Making KiwiSaver more cost-effective

AGENCY DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This Regulatory Impact Statement has been prepared by Inland Revenue and the Treasury.

It provides an analysis of options for changes to KiwiSaver, to boost national savings. These are scheduled to be announced as part of Budget 2011.

The Government has signalled its desire to focus Budget 2011 on measures which will boost national savings as this will help to address economic imbalances and reduce New Zealand’s indebtedness, either by enabling current debt to be paid down or by reducing the need for borrowing in the future.

As the quickest way for the Government to improve national saving and reduce economic imbalances would be to improve its own saving position,[1] the identification and development of options quickly narrowed to those most likely to reduce Government spending without undermining the primary purpose of KiwiSaver.

A key assumption is that any changes should be directed towards altering the balance of contributions made by each of the contributing parties (the member, their employer and the Crown) away from public funding and towards private saving. Any Crown incentives to save through KiwiSaver should be directed appropriately. This paper also analyses options for increasing the numbers enrolled in KiwiSaver, and/or increasing the amount of members’ contributions, again with the aim of boosting national savings, and encouraging private savings behaviour that is focused on the long term return and specifically individual retirement.

The impacts of each option cannot be easily modelled using historical data, given the relative newness of the KiwiSaver savings model, nor is international comparison always appropriate, given many of KiwiSaver’s unique features and New Zealand’s TTE model of taxation[2]. Our analysis of the options is therefore dependent on behavioural assumptions, for which there is minimal empirical evidence, about individuals’ and employers’ responses to changes in savings incentives and other regulatory requirements. In modelling the effects on the Net International Investment Position (NIIP), the assumption has been made that additional national savings reduces the current account deficit rather than increases overall domestic investment. To the extent that these changes instead boost domestic investment, the impact on the NIIP will be smaller. These assumptions are consistent throughout, so we have greater confidence in the relativity between the various results than in their absolute levels.

We have reconciled, as far as possible, each option for change with the primary purpose for which KiwiSaver was designed, which was to provide an easy-access, work-based low-risk product, which would enable individuals and households who might not be saving enough for their retirement to do so. KiwiSaver was not explicitly designed as an instrument to boost national savings and so, although it can make a positive contribution, its effectiveness towards this objective is likely to be more limited.

We have also recognised that KiwiSaver is less than five years old. Since its launch in July 2007, there have been several significant changes to contribution requirements, which have mostly affected employees and their employers, as well as new providers entering into the KiwiSaver market. The KiwiSaver industry has not experienced any period of stability in which to establish its core products, and this uncertainty and unpredictability is not helpful to either the industry or savers. Any changes made at this point in time should therefore be sustainable and, where possible, use pre-existing features of KiwiSaver rather than introduce new features.

Our analysis draws on matters identified by other interested agencies, including the Retirement Commissioner and the Government Actuary. As the need for Budget secrecy has limited opportunities for formal public consultation in the usual manner under the Generic Tax Policy Process, we have also drawn on the considerations of the Savings Working Group[3], which was commissioned by the Minister of Finance in August 2010 to provide a point of reference for the Government in developing its medium-term savings strategies.

The proposals do not impair private property rights, restrict market competition, reduce the incentives on businesses to innovate and invest, or override fundamental common law principles.

The proposal to increase the compulsory employer contribution rate at the same time as increasing the minimum employee contribution rate will lead to some additional costs on businesses that employ staff, by increasing labour costs; in the short term this may reduce firm profitability. The additional cost for employers is likely eventually to be reflected in wage settlements for all employees, although this impact should be limited as the economy and nominal wage growth are expected to strengthen from the end of 2011.

Steve Mack

Principal Advisor, Tax Strategy

The Treasury

6 April 2011

Dr Craig Latham

Group Manager, Policy

Inland Revenue

6 April 2011

INTRODUCTION

1. This RIS summarises officials’ analysis of various changes to KiwiSaver that have been considered in order to deliver two objectives:

- to help return the Crown to surplus sooner by reducing the fiscal costs of KiwiSaver; and

- to continue to encourage increased levels of private household savings, and a long-term savings habit and asset accumulation, in order to increase well-being and financial independence in retirement.

2. Analysis of each of the key options for change is summarised in the table at paragraph 16.

STATUS QUO AND PROBLEM DEFINITION

Economic Growth and Saving Levels

3. The Government is concerned that, in recent years, New Zealand’s economic growth performance has been poor by developed country standards, and our relative position in the OECD is well below average. In addition, as the Savings Working Group (SWG) noted, New Zealand’s low rate of saving has created a dependency on foreign capital to fulfill domestic investment demand. This has created a large and persistent gap between New Zealand’s investment and saving levels, as reflected in the current account deficit over several decades. The SWG agreed with the analysis set out in the Treasury’s discussion document[4] that this presents two serious economic problems: firstly it makes the New Zealand economy too vulnerable to market shocks; secondly, it has an adverse impact on economic performance, especially growth[5].

4. In addition, the Government has signalled its desire to move quickly to reduce Government debt and return to fiscal surplus. Lifting the level of national savings would help to address economic imbalances, reduce New Zealand’s indebtedness and thus possibly contribute to improved economic growth. The Government has indicated that the focus of Budget 2011 will be on national savings and investment. As noted by the SWG, returning towards fiscal surplus, as well as encouraging private individuals to save more, is an important component of improving the national savings position.

KiwiSaver

5. The objective of KiwiSaver, as set out in the KiwiSaver Act 2006, is “to encourage a long-term savings habit and asset accumulation by individuals who are not in a position to enjoy standards of living in retirement similar to those in pre-retirement”. It was not explicitly designed as an instrument to boost national savings per se, but instead to increase individuals’ well-being and financial independence in retirement, as a complement to New Zealand Superannuation for those who wish to have more than a basic standard of living in retirement.

6. KiwiSaver was designed with features intended to encourage long-term savings, by making it easy and attractive to join, providing relatively limited opportunities to access savings once enrolled, and providing individual savers with opportunities to exercise as much or as little choice over their savings as they wish to or are able to. Although membership is available to all eligible New Zealand residents, many of the key features of KiwiSaver are those of a work-based superannuation scheme, such as the automatic enrolment of employees, deductions at source and (compulsory) employer contributions.

7. The numbers enrolling in KiwiSaver have consistently outstripped initial forecasts, and the present membership is double that forecast in 2007. The latest KiwiSaver Evaluation report[6] concluded that KiwiSaver’s features are working as intended, particularly in attracting people into a savings product. It also concluded that KiwiSaver has generated some level of new savings, over and above what would have been saved in the absence of KiwiSaver.

8. KiwiSaver therefore has a potentially significant role to play in increasing national savings, both through the savings contributions made by members, and in promoting awareness about savings and inculcating a savings habit among a large majority of the population. However, the cost to the Government is significant and this restricts the benefits to national savings; a recent Colmar Brunton survey indicates that the percentage of contributions that were “new” savings (as opposed to diverted from other forms of saving) at approximately 29%[7]. This is partly because some of the private funds going into KiwiSaver accounts are being diverted from other savings rather than being additional saving, and partly because the Government’s contribution means that individuals do not have to save as much themselves to achieve the same eventual outcomes.

OBJECTIVES

9. One of the Government’s key goals for 2011 is to build the foundations for a stronger economy. The Government has therefore outlined several objectives, including building savings and investment in New Zealand. The Prime Minister has signalled the intention to focus Budget 2011 on measures which will boost national saving, by encouraging additional saving from private individuals and through Government efficiency savings. Further information on these objectives was provided in the Prime Minister’s Statement to Parliament on 8 February 2011[8]:

Building Savings and Investment: In order to reduce our dependence on foreign lenders, New Zealand needs to build up the pool of Kiwi-owned savings and investment, held by both the Government and everyday New Zealanders. That will be the focus of this year’s Budget…The Government will also consider ways in which we can encourage New Zealanders to increase their private savings and investments. Last year we asked the Savings Working Group to consider policy options to increase national savings, and it presented its report last week. The Government will consider this report very carefully. We expect to announce resulting policy decisions in the 2011 Budget.

10. The objectives for any changes to KiwiSaver are:

- to help return the Crown to surplus sooner by reducing the fiscal costs of KiwiSaver[9], and

- to continue to encourage increased levels of private household savings, and a long-term savings habit and asset accumulation, in order to increase well-being and financial independence in retirement.

11. Each of the options for change that could meet one or more of these objectives was assessed against a matrix of criteria:

- impact on national savings, which was measured as the effect on the Net International Investment Position (NIIP) over ten years

- fiscal costs/fiscal savings

- economic impacts, such as the likely effect on labour costs and hence employer costs and profitability

- social welfare and distributional impacts on those on the lowest income

- alignment with the broader KiwiSaver framework and objective.

12. In making this assessment, the strongest weight was given to measures which reduced fiscal costs, in light of earlier advice from the Treasury that reducing the deficit sooner is the most important contributor to national saving. Additional weight was also given to options that did not threaten other aspects of the economic well-being, such as employment, or the social welfare of those on the lowest income. Further analysis of each option, including variations and dependencies between the options, is discussed below.

13. On a practical level, attention was also quickly directed towards options for change that could be developed in the immediate and short term, given the tight time-frames for delivery in Budget 2011. Certain options were therefore not taken forward, or further consideration within a longer time-frame was recommended, as the necessary consultation and implementation work could not be delivered within the timescale of this Budget.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS

14. Each of the key options for change that were analysed are summarised in the table below. Paragraph options in larger, bold text are recommended as part of the Budget 2011 savings and investment package:

| Objective | Description | Summary assessment of impact on | Comments | See RIA paragraph | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National savings Impact on NIIP over ten years (% points) |

Fiscal savings (costs) over 4 years ($million) | |||||||

| Reducing the fiscal cost of KiwiSaver | Lowering the maximum member tax credits (MTC) to $521.43 | 0.4–0.9% | The individual effect of lowering the maximum MTC | 1,600 | The individual effect of lowering the maximum MTC | • Will make KiwiSaver less attractive, but may encourage private contribution to raise final accumulations to replace government contributions • May mean fewer savings directed from other forms of savings if these become relatively more attractive. • Main impact on those contributing >$521.43/year • In conjunction with other changes, consistent with KiwiSaver objectives. |

Para 24-29 | |

| Lowering the rate of matching payment (to 50c per $1 contribution) | 0.3–0.7%. | The individual effect of lowering the matching rate | 1,300 | The individual effect of lowering the matching rate | • Level of private contribution required to maximise Government contribution unchanged at $1042.86. • No change to employer costs. • Lower as well as higher level contributors affected. • In conjunction with other changes, consistent with KiwiSaver objectives. |

Para 24-29 | ||

| 0.5–1%. | Combined effect of these two options[10] | 2,000 | Combined effect of these two options | |||||

| Removing the employer superannuation contribution tax (ESCT) exemption | 0.6–0.7% | 700 | • Higher rate taxpayers lose more than lower rate tax payers compared to present setting. • Marginal increase of cost to employers. • In conjunction with other changes, consistent with KiwiSaver objectives. |

Para 35-39 | ||||

| Reducing or removing the kick-start payment | Not modelled separately | Not modelled separately | • Cost of kick-start expected to decline anyway. • Same absolute impact across income levels. • No change to employer costs. • Inconsistent with KiwiSaver objectives. |

Para 30-34 | ||||

| Increased household savings | Increasing compulsory employer contribution rate up to 4% (matching employees’ contributions) | With existing subsidies | 0.9–1.2% | (240) | • Increase in employer costs likely to lead to reduced business profitability in short term, and lower wages over the longer term. • Encourage savings and increased private contributions. • Consistent with KiwiSaver objectives. |

Para 55 - 59 | ||

| With reduced subsidies[11] | 2.2–2.6% | 2550 | ||||||

| Encouraging increased private household savings | Increase minimum compulsory employer contribution to 3% | Existing Subsidies | 0.35-0.5% | - | • Increase in employer costs likely to lead to reduced business profitability in short term, and lower wages over the longer term. • Makes membership more attractive • Consistent with KiwiSaver objectives |

Para 55 - 59 | ||

| Reduced Subsidies | 1.5-2% | 2700 | ||||||

| Increased default contribution rate for employees to 4% | Existing subsidies | 0.1% | (30) | • No change to employer costs. • Consistent with KiwiSaver objectives. Encourages individuals who can afford to do so to contribute at higher rates |

Para 53 - 54 | |||

| Reduced subsidies | 1.2–1.8% | 2650 | ||||||

| Introducing an intermediate 3% employee contribution rate | Not modelled separately | Not modelled separately | • Provide greater flexibility for KiwiSaver members to choose most appropriate contribution rate • Increases complexity. Inertia means take up likely to be low |

Para 62 | ||||

| KiwiSaver membership compulsory | Existing subsidies | 0–0.7% | (2700) | • “Portfolio” costs of mandating savings in funds. • Timing of savings may not suit individual’s present circumstances. • Significant increase in employer costs. • Inconsistent with KiwiSaver objectives of “encouragement.” |

Para 40 - 47 | |||

| Reduced subsidies | 2.2% | 900 | ||||||

| One-off enrolment exercise (4% default) | Existing subsidies | 0.1–0.5% | (1500) | • Increase in employer costs. • Consistent with KiwiSaver objectives. |

Para 48- 52 | |||

| Reduced subsidies | 1.80–2.1% | 1900 | ||||||

| Increasing minimum employee contribution rate to 3% | Existing subsidies | 0.1–0.2% | (115) | • Increases contributions and final accumulations for individual members • A small number may stop contributing, thereby missing out on employer and government contribution. • Consistent with KiwiSaver objectives. |

Para 60 - 63 | |||

| Reduced subsidies | 1.4–1.9% | 2600 | ||||||

| Lowering minimum employee contribution rate (considered in conjunction with compulsion)[12] | Not modelled separately | Not modelled separately | • Misapprehension about appropriate level of retirement savings. • May encourage participation. • Inconsistent with KiwiSaver objectives. |

Para 64 | ||||

15. As noted previously, the Government commissioned the independent Savings Working Group (SWG) to review medium-term savings strategies; their remit included a review of KiwiSaver’s contribution to this strategy. Treasury and Inland Revenue officials provided support to the SWG. Other policy reports were received by Ministers regarding KiwiSaver’s role in the overall savings package.

16. A large number of potential changes to KiwiSaver have been discussed in the public arena over the last five months because of the SWG review, such as the KiwiSaver default provider arrangements, management of funds, consumer financial literacy, and provider fee structures. Some potential options for change were considered by the SWG and are discussed in their interim and final report. Some of their recommendations are within the remit of other Government departments; for example, the Ministry of Economic Development[13] recently issued a discussion document regarding periodic reporting.

17. This RIS does not replicate all of the discussions about potential options for changes to KiwiSaver that have been considered. Instead, it summarises officials’ advice on the development of a preferred package of feasible changes, assessed against the criteria outlined in paragraph 11, to deliver the Government’s objectives for Budget 2011.

18. The options considered in more detail in developing this preferred package were:

Key objective: Reduce the fiscal costs of KiwiSaver

- Changing KiwiSaver incentives and entitlement rules: member tax credits (MTCs), initial Crown contribution (“kick-start”), and employer superannuation contribution tax (ESCT) exemption.

Secondary objective: Encourage increased levels of private household saving

- Increasing membership of KiwiSaver, including some form of compulsion

- Increasing contributions from existing members

- Increasing contributions from employers.

19. In exploring the options under each objective, the directional effect on the other objective had to be considered. For example, an increase in KiwiSaver membership would, in the short term, increase the amount of “kick-start” payments made and, in the longer term, increase the numbers claiming MTC. An increase in members’ contribution levels could also lead to increased MTC payments; so although both changes might increase private savings, they would move against the objective of reducing the fiscal costs of KiwiSaver.

20. For most options, there were a number of potential variations. Some options were inter-dependent, while others were considered as complementary but independent. Many of the options considered had several sub-variations; for example, varying contribution rates per contributor, or re-structuring incentives such as the kick-start and member tax credit amounts and entitlement/payment mechanisms. The main variations that were explored are discussed under each option below.

KiwiSaver options explored

Reducing fiscal costs by changing KiwiSaver subsidies: General

21. One of the biggest impacts the Government can have on national savings is by returning to a budget surplus as quickly as is reasonably possible. An effective way to achieve this is by cutting low-value fiscal spending. Under the current KiwiSaver settings, there are opportunities to achieve lower fiscal costs while having minimum impact on encouraging household saving. In order to reduce the fiscal costs of KiwiSaver, the various subsidies must either be reduced or removed, whether for all members or through more direct targeting of subsidies to particular member groups.

22. Government contributions to KiwiSaver through direct subsidies (kick-start and MTCs) and forgone tax (ESCT exemption) total over $1 billion per annum; this is estimated at about 40% of total contributions in 2009/10. The current settings mean that Government contributions will make up a significant proportion of individual KiwiSaver balances at retirement. Empirical evidence suggests that this expenditure is delivering poor value in terms of leveraging additional savings. Some of the savings going into KiwiSaver accounts are being diverted from other forms of saving rather than additional saving. Also those individuals saving towards a target level of income in retirement may reduce their own level of saving in response to Government contributions, since they can achieve the same final accumulations at less expense to themselves. Genuine additional private saving may therefore be as little as $29 for each $100 contributed by Government.

23. Although two thirds of members in the Colmar Brunton survey cited Government subsidies as one of the reasons why they joined KiwiSaver, other features such as auto-enrolment, ease of contribution (deductions from pay) and employer contributions were also important[14]. The ESCT exemption, being relatively hidden, did not feature in the survey responses.

Changing KiwiSaver subsidies: Member tax credits

24. The Government currently pays a member tax credit (MTC), up to a maximum of $1,042.86 a year, into the account of members aged over 18, which matches contributions made by the individual during the year. MTC payments for the year to 30 June 2010 totalled about $665 million.

25. Reducing the maximum annual MTC payment alone (i.e. without changing the matching rate) would provide immediate fiscal savings. It would also reduce the total accumulation in individual KiwiSaver accounts, compared to leaving the MTC maximum amount unchanged. However, other changes, such as increasing the matching rate or, notably, increased employer contributions, will work in the opposite direction to raise total accumulations.

26. The MTC is designed to encourage and reward the development of a regular pattern of savings once members have joined KiwiSaver. However, the current $1 to $1 matching rate is particularly generous by comparison with other savings options; it doubles the amount of contributions made (up to $1,042), effectively providing a minimum 100% return on these contributions.

27. MTCs are simple and relatively easy to administer because they are linked to the level of a member’s contributions paid in a year rather than to the member’s income. The cap ensures that lower contributors, who tend to be lower income earners, get a larger benefit proportionate to their contribution. The possibility of making a link between maximum entitlement, or matching rates, and a member’s income (whether just active or active and passive income) was considered. However, the administrative reality is that any such link is not possible without prohibitively costly system changes, and even then would take several years to implement.

28. The SWG suggested increasing MTC payments for those on lower incomes by increasing the matching rate to $2 MTC for each $1 member contribution, in order to increase the amounts received by those on lower incomes making lower contributions. However, as well as increasing the fiscal cost of the MTC this could also have the effect of encouraging/enabling those on higher incomes to reduce their contributions, either by reducing their contribution rate or making fewer voluntary contributions (if self-employed) in order to maximise their MTC.

29. The converse matching position, for example 50c per $1 member contribution, should not lead to a reduction in contributions from those currently contributing to the maximum MTC level, since they would still need to contribute the same to maximise the Government contribution. A reduction in the matching rate spreads the impact more broadly than reducing the cap alone, which would deliver fiscal savings only in the case of KiwiSaver members contributing above the level of the cap. The cap would mean that the subsidy would remain broadly progressive, and still reflect a greater proportion of total KiwiSaver inputs for low income earners than for higher income earners.

Changing KiwiSaver incentives: Kick-start

30. The $1,000 kick-start payment from the Crown is a highly successful “recognition” feature for KiwiSaver; 92% of all respondents to the Colmar Brunton survey[15] (both KiwiSaver and non-KiwiSaver members) were aware of the kick-start. Payments for the last 12 months to February 2011 totalled $354.6m.

31. With a projected increase in KiwiSaver membership of approximately 300,000 members over the next four years, there would be fiscal savings to be made in removing or reducing the kick-start incentive. However, this could damage KiwiSaver’s attractiveness to new members. There is a strong psychological boost attached with such an early initial increase in a member’s funds and, on balance, the potential damage to public perception and to the initial attractiveness of KiwiSaver outweighs the diminishing value of fiscal savings made by reducing or removing the iconic kick-start payment.

32. The Savings Working Group recommended a gradual ‘drip-feed’ of kick-start payments, to be matched to members’ contributions. However this would have minimal effect on costs, reduce the immediate psychological boost of a $1,000 incentive and would effectively make this payment a duplication of MTCs, which are intended to encourage regular contributions.

33. Removing or delaying payment of the kick-start to those under eighteen was also considered. The 2010 KiwiSaver Evaluation, conducted by Inland Revenue’s Evaluation Service[16], identified that among those parents who had enrolled their children, the Government kick-start contribution was the most common reason provided; 83 percent said this was a factor in enrolling their children, while 34 percent said this was the most important factor in their decision. However, the value of accounts for most under eighteens is relatively low; a large numbers of children’s accounts appear to hold nothing more than the $1,000 kick-start, indicating that this practice is doing little or nothing to raise private savings and encourage a savings habit via KiwiSaver.

34. There are therefore potentially some fiscal savings from delaying the payment of the kick-start for under-eighteens, for example, until their eighteenth birthday. However, such a change would add to the complexity of KiwiSaver, and yet the overall fiscal savings are likely to be minimal. Any KiwiSaver changes targeted at only this age group should form part of any wider consideration of how to boost savings levels for young people, and install good savings habits from a young age.

Changing KiwiSaver incentives: Employer superannuation contribution tax exemption

35. Employer contributions (currently up to 2% of employee remuneration) to employee KiwiSaver accounts and complying superannuation funds are presently exempt from ESCT. The exemption is estimated to cost the Government about $175 million a year in revenue forgone.

36. The Savings Working Group recommended that the existing exemption from ECST be removed; by its nature it is almost invisible to KiwiSaver members, and so is the least-value of the incentives in terms of raising levels of private saving. It is also the most regressive of the KiwiSaver subsidies, since those in higher tax bands get a proportionately greater benefit; 50 percent of the benefit goes to the top 15 percent of earners. Officials also recommend removing this exemption on similar grounds.

37. As part of removing the exemption, however, consideration should be given to how ESCT is computed on employers’ contributions. The legislation currently gives two main methods to calculate ESCT. The default method allows employers to deduct ESCT at a flat rate of 33% from eligible superannuation contributions, while the “progressive scale” method allows lower ESCT rates to be applied to employers’ superannuation contributions in relation to each individual’s previous year’s salary, wage and superannuation contribution levels.

38. Inland Revenue’s administrative data is insufficient to identify which methods are used by employers. However, although it is recognised that the default method is simpler for employers to apply and so reduces compliance costs, it does mean that lower-income employees who are affected will be more heavily taxed than they would be the case compared to the “progressive scale” method and compared to the rate at which their salary or wages are taxed. This results in less money going into their superannuation accounts.

39. It is therefore proposed to require all employers to use the progressive scale system at the same time as removing the ESCT exemption. This should not be a particularly difficult change for employers using commercial payroll systems that already have this functionality. For ease, the timing of the change should be matched to the annual payroll cycle (1 April 2012). Employers preparing manual payrolls will need to include an additional calculation for ESCT when calculating KiwiSaver contribution amounts. Inland Revenue guidance, calculators and calculation tables will be available to assist with this.

Encourage increased levels of private household saving

Increasing membership: Compulsory versus voluntary

40. SWG and Government officials considered the impacts of KiwiSaver becoming a compulsory scheme. Variations included compulsion for employees only, with compulsory contributions deducted from pay; compulsion for all eligible adults; or compulsion for adults over a certain age or from a particular income level. This would also require changes to the current settings for “contribution holidays”. The point of compulsion would otherwise be negated by the ability of members to choose not to contribute. Issues regarding market fees and investment strategy would need to be fully resolved in advance of any element of compulsion being introduced.

41. The present KiwiSaver model, although available to non-employees, is primarily marketed and designed as a work-based voluntary superannuation savings scheme. For a universal enrolment, as well as new enrolment mechanisms for those outside the employed workforce, new contribution models would need to be introduced to require and collect savings contributions from non-employed persons. Similar issues arose if compulsion was linked solely to age or income levels.

42. Compulsion for all employees, building on the existing KiwiSaver design, would therefore be more practical than a universal enrolment. It is estimated that KiwiSaver membership would increase by an estimated 730,000; the impact on national savings depends in part on other KiwiSaver settings, such as the contribution rate and Crown incentives, but would be expected to be positive.

43. However Inland Revenue and officials from the Treasury consider that these benefits KiwiSaver need to be weighed against the welfare costs for people at the lower end of the income distribution scale, who may be forced to reduce their spending on essential items in the present time in order to increase their income in retirement. The SWG considered the same point, and referred to this in their report as “timing costs”.[17]

44. The SWG also noted that compulsion to save into KiwiSaver has a “portfolio cost”, in that it forces some people to invest in superannuation when they would rather invest in something else, such as housing, an enterprise business, or in a savings scheme that provides earlier access to funds, such as for education purposes. The Retirement Commission also recommended against compulsion.[18]

45. Treasury modelling also indicates that, following compulsion, 30 percent of any new savings would be expected to come from 60 percent of new members, each earning less than $40,000. This suggests that the increase in national saving is unlikely to be justified by the negative impact on present welfare for such low earners, who are themselves unlikely to value the benefits in terms of increased consumption later over decreased consumption now.

46. Linking compulsion for employees to wage levels or age were possible variations under this option that might have helped to alleviate some of the concerns over both “timing costs” and “portfolio costs” for savers. However, these variations would add to the complexity of KiwiSaver, and create additional compliance requirements for employers.

47. On balance, the modest increase in national savings that could be expected from introducing compulsion was outweighed by the harmful welfare impacts on some groups of people, and the increase in fiscal costs if the KiwiSaver subsidies were retained, even in a reduced form. Further, a move towards compulsion now was unlikely to be able to be readily reversed in future if it no longer aligned with the Government’s longer term savings and investment plans.

Increasing membership: enrolment exercise (with option to opt out)

48. Some increase in KiwiSaver membership could nevertheless still be delivered through existing mechanisms, if the increase is targeted to attract the people most likely to continue to contribute. Employees are the prime market; behavioural analysis indicates that there is a strong “inertia” factor for contributions by this group, which is assisted by the automatic deduction of contributions from source.

49. Inland Revenue commissioned Colmar Brunton to undertake a survey to assess the outcomes of KiwiSaver for individuals. Colmar Brunton reported in July 2010[19]. Inter alia, the survey asked respondents why they had not become members of KiwiSaver: 28% had not got round to joining, while a further 13% wanted more information about KiwiSaver. This could indicate that, of the employed population who are not already members of KiwiSaver, over a third would not be averse to joining and so would be likely to remain a member if automatically enrolled by their employer.

50. Officials therefore considered a one-off enrolment for all employees who are not already members of KiwiSaver or a complying superannuation scheme. The exercise would provide employees the option to opt out before being enrolled in KiwiSaver by their employer. Such an exercise was estimated to deliver up to 330,000 new members. This differs from the SWG recommendation of a one-off exercise using the current auto-enrolment process, by avoiding the significant compliance and administration costs for employers to make deductions from wages, which are later refunded by Inland Revenue where employees subsequently opt out. Even so, there would be costs to employers, both in running the exercise and in increased employer contributions for new members.

51. Such an increase in KiwiSaver population would also significantly increase the fiscal costs, both in the short term through higher kick-start payments ($330 million in the first year) and ongoing through the MTC (around $100 million per year). Given the key objective to reduce fiscal costs, this was not regarded as the appropriate time to consider running such an exercise.

52. The SWG suggested that the immediate impact of the increased kick-start payments could by managed down by spreading payment over five years. However, this would have a limited effect on the overall fiscal cost and would have negative incentive impacts. The $1,000 kick-start is highly successful ‘recognition’ feature for KiwiSaver; 92% of all respondents to the Colmar Brunton survey[20] (both KiwiSaver and non-KiwiSaver members) were aware of kick-start, compared to only 58% who knew about member tax credits (MTCs). The spreading method would have to be applied to all new members, not just those enrolled as part of the exercise; it would therefore reduce the attractiveness of the kick-start payment in encouraging members to join in future.

Increasing contributions: increasing default contribution rate for auto-enrolled employees

53. The “default contribution rate” is the rate at which employees who are automatically enrolled into KiwiSaver by their employers will start contributing, unless they actively choose a rate. The default rate now stands at 2% of wages. However, of those joining before 1 April 2009, when the default employee contribution rate was 4%, 75 percent of members are still contributing at least 4%; that is, they did not take advantage of the introduction of the 2% minimum rate from 1 April 2009. Only 20 percent of members joining on or after 1 April 2009, when the default rate was set at 2%, have actively chosen a higher rate.

54. Thus, for many members, the default rate at which they start making KiwiSaver contributions governs the level of on-going contributions (“set and forget”). However, those employees who have chosen to move to a lower contribution rate have tended to be lower-income. This suggests that affordability does have some influence, since the cap on Government contributions means that incentives are already stronger for low income members to contribute at above-minimum levels; and that 4% may be too high for some members.

Increasing contributions: increasing compulsory employer contribution rate

55. Compulsory employer contributions both increase individual final accumulations and, especially if matched to employee contributions, are a strong way to encourage individuals to save towards retirement. With the exception of higher-paid executives where retirement contributions are a key part of a total remuneration package, many employees do not traditionally regard their employers’ contributions as deductions from “their” wages, even though the additional cost to employers from making contributions is likely eventually to find its way through to lower wages (including for those not members of KiwiSaver).

56. At present, the minimum employer contribution is 2% of employee wages. The rate was originally set at 1% with the intention that this should increase by 1 percentage point each year until it reached 4%, but it was capped at 2% in 2008. Internationally, employers traditionally contribute at much higher levels; for example, the Australian scheme involves an employer contribution rate of 9%.

57. In contrast to employee contributions, where many employees are contributing above the 2% minimum rate, 90 percent of employer contributions are made at 2%. A requirement for employers to raise their minimum contribution would therefore make a fairly significant impact on total KiwiSaver accumulations.

58. Higher employer contributions would increase labour costs in the short term. A delayed or staged introduction of an increased minimum rate for employer contributions (either with or without an employee matching requirement) would better enable employers to prepare for and manage these changes alongside other business costs. In the longer term higher contributions are likely to be reflected in lower wage settlements, but this impact should be limited as the labour market and nominal wage growth are expected to strengthen from the end of 2011.

59. If the requirement were that employers should raise their own contributions only where employees contribute above the minimum rate, it would reinforce the incentive for employees to raise, or maintain, their own contribution rates. However, the well-documented power of inertia raises the risk that many employees would still take no action and leave contribution rates unchanged even though they could afford and would derive greater benefits from a higher rate. Where subsidies are reduced as set out above, such employees, who are most likely to be in the lower income bracket, would see reductions in both their employer contributions (because of removal of the ESCT exemption) and in the Government’s MTC contribution. Making the increased employer contributions dependent on voluntary action by individual members may therefore mean that many lower-income members see no individual benefit.

Increasing contributions: increasing minimum employee contribution rate

60. Increasing the current minimum employee contribution rate would increase the amounts of employee savings. It would also move some way to address the risk that the current 2% minimum and default rate setting sends the wrong message regarding the appropriate level of savings that individuals should be making in order to provide an adequate retirement income.

61. This must be weighed against the “timing costs” for people at the lower end of the income distribution scale. A higher minimum contribution effectively increases the price of contributing to KiwiSaver. People who cannot afford to contribute a revised minimum would be forced onto contributions holidays or never join in the first place, thus missing out on Government and employer contributions. So a very sharp increase in the minimum contribution rate may not deliver very much by way of additional household savings.

62. Allowing an additional 3% employee contribution rate, between the existing 2% minimum and the next optional contribution rate of 4% could be a helpful option for some members. Matching employer contributions at higher rates would reinforce the incentive for employees to contribute more where they can, and help to ensure that there is little movement from employees the other way (that is, downwards to 3%). However, the risk of down-shifting may not actually be very high, given that employees on 4% already have the option to reduce their contribution rates, and the additional cost to employers may not therefore be justifiable. The additional costs to both Inland Revenue and employers of introducing this further option would be very modest, as would be the introduction of further contribution rates, for example 5%, 6% etc.

63. Nevertheless, from the point of view of the individual KiwiSaver member there is a strong interest in keeping the scheme as simple and clear as possible; and in serving the interests of those who take no action. The addition of further options which require active decision making on the part of members and which many are likely to ignore anyway, even though they could benefit from them, would work against that objective. Members who are keen to engage more fully can always make voluntary contributions to increase their final accumulations and (for those on lower incomes) Member Tax Credit receipts.

Increasing contributions: minor change options

64. Other more minor change options that were considered but not recommended for the Budget 2011 package are summarised below:

| Option | Comment | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Lowering minimum contribution rate to 1% | Considered alongside compulsion. Would reduce the amount employees would be required to save, but could overcome “timing” concerns in mandating savings. |

Not recommended: potential negative effect on national savings. From a retirement savings perspective, this is an unreasonably low rate of savings for all but the lowest-income families (from whom NZ superannuation alone already provides a reasonable pre and post income match). May increase misperceptions about the appropriate rate of savings. |

| Auto-enrolment extended to employees under 18 | Recommended by the SWG, along with extending compulsory employer contributions and MTCs in order to increase participation in KiwiSaver. | Not recommended; retirement savings not high priority for this age-group. Estimated amounts saved into KiwiSaver would be relatively low. Increased member tax credits would increase fiscal costs. Negative impact on short-term employer costs and consequently on youth employment outweighs potential savings increases. |

| Reducing non-contributory periods (“contribution holidays”) | After the first year of membership contributions holidays may be taken for any reason, and they may be taken successively, effectively allowing employees not to contribute to KiwiSaver. They do not receive any employer contributions during this time. | Further work recommended. Ability to cease contributions is a useful “safety valve” for employees at difficult points in their life. Reducing holiday periods or imposing stricter criteria might lead to some increase in savings from existing members, although a few may simply choose not to join KiwiSaver at all |

CONSULTATION

65. Due to the need for Budget secrecy, and the short time-frames involved in developing a KiwiSaver-related savings package for Budget 2011, the ability to consult in the usual manner under the Generic Tax Policy Process has been constrained.

66. However, many of the issues noted in this paper have already been considered by the SWG which, in discussing New Zealand’s medium-term savings strategies, was particularly asked to consider the role of KiwiSaver in improving national saving outcomes, including the operation and outcomes of KiwiSaver, and the fairness and effectiveness of current KiwiSaver subsidies. The SWG made several recommendations in this regard, which have been discussed above.

67. The SWG received considerable public feedback during the process; the submissions it received and its interim and final reports are available on the Treasury website. Officials have been able to view these submissions and listen to specific concerns raised by interested groups during the SWG process, albeit that there has been no active consultation by officials.

68. The Retirement Commissioner also released her triennial review of retirement income policy on 7 December 2010, which discussed KiwiSaver, costs, and the effectiveness of incentives, as well as making KiwiSaver compulsory.

69. Thus, some of the debate about KiwiSaver reforms, and in particular whether KiwiSaver should remain a voluntary scheme, have been in the public domain for some time, with the ability for the public to provide comment. This provides some alignment with the Generic Tax Policy Process.

70. Some implementation decisions, such as the staged increase in the compulsory employer contribution rates, and the possible one-off enrolment exercise for existing employees, have been deferred until after the Budget. This will enable detailed consultation to take place, and any specific technical issues to be identified and addressed at the detailed design stage.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

71. The KiwiSaver change package recommended for Budget 2011 mostly aims to reduce fiscal costs by transferring the costs of KiwiSaver from the public to the private sector, by reducing the Government subsidies. The proposed measures could also encourage higher private contributions. However, further public education and awareness about the continuing importance of individual saving, to ensure resources are over and above New Zealand Superannuation in retirement, are highly desirable. The promotion of educational resources, such as the Retirement Commission’s Sorted website, is strongly recommended to encourage individuals to take an active interest in considering their own longer term needs and how best to provide for these.

72. The table below shows a summary of recommendations and cumulative impacts:

| The additional effect of each recommended change | Impact on NIIP (over 10 years) | Fiscal savings (costs) over 4 years ($million) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halve matching rate (50c per $1) and maximum amount ($521.42) of member’s tax credits | +0.5 – 1% | 1,998 | Large fiscal savings. Member still contributes $1042.86 to maximise MTC; encourages private savings |

| Additional effect of employer superannuation contribution tax (ESCT) exemption | +0.6 – 0.7% | 678 | Large fiscal savings. The ESCT represents the least-value, and most regressive, of all the subsidies. |

| Additional effect of increasing minimum contribution rate for employees to 3% | +0.2% | (60) | Should be affordable for most and deliver greater final accumulations than the present minimum |

| Additional effect of compulsory employer contributions to match employees (up to 3%) | +0.35 – 0.5% | -* | Increases absolute amount of contributions. |

| Total | 1.85 – 2.25% | 2,616 |

* This does not include any additional cost to the crown as an employer from higher employer contributions

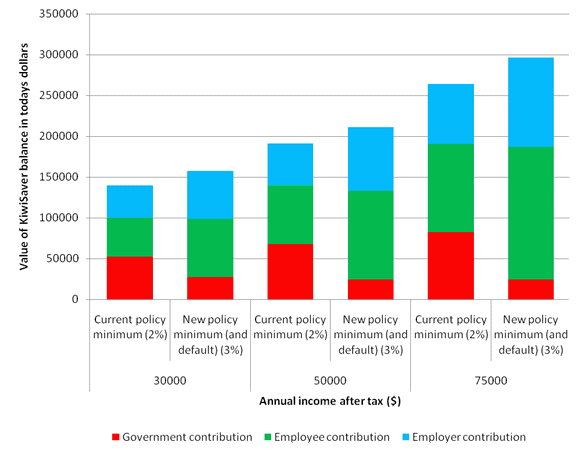

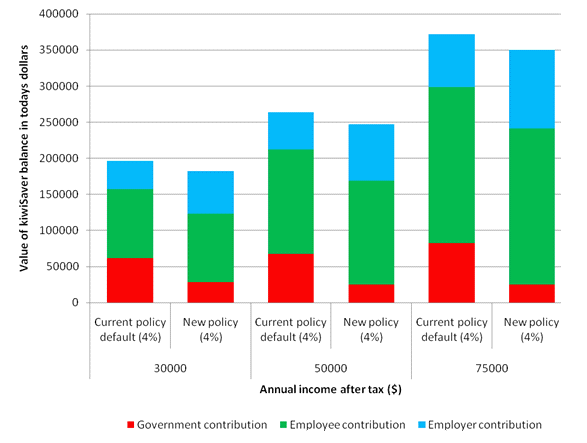

73. The figures below illustrate the impact of the proposed changes, as a package, on the KiwiSaver fund of an employee who opts in at 30 years old, for different contribution rates. Figure 1 shows that an employee who is contributing 2% under the current policy settings and contributes 3% after the policy change would have a significantly higher balance at retirement, despite the sizable decrease in Government contribution. Figure 2 shows that if an employee is contributing 4% under the current policy settings and continues contributing 4% after the policy change, he would have a slightly lower balance at retirement than under present settings.

Figure 1. Forecast composition of a KiwiSaver fund at retirement for an employee who opts in at age 30* (comparing minimum employee contribution rates)

Note: Employee contribution rates in parentheses.

* Assumes real wage growth of 1.5% per annum, that funds earn a real return of 4% per annum and that PIE and ESCT thresholds are indexed to inflation

Figure 2. Forecast composition of a KiwiSaver fund at retirement for an employee who opts in at age 30* (comparing 4% contribution rates)

Note: Employee contribution rates in parentheses.

* Assumes real wage growth of 1.5% per annum, that funds earn a real return of 4% per annum and that PIE and ESCT thresholds are indexed to inflation

IMPLEMENTATION

74. Officials have recommended that the proposed changes to the ESCT and the Member Tax Credit should be included in Budget night legislation which will go through all the stages in the House in a single Parliamentary day. This is to allow sufficient time for implementation, both for employers and Inland Revenue.

75. The removal of both the ESCT exemption and the 33% flat-rate calculation method would come into effect on 1 April 2012. This is to tie in with the start of the tax year and so take advantage of the various updates to payroll systems and employer information leaflets that are already scheduled to be made at that date.

76. The proposed changes to reducing the MTC matching rate to 50c per $1 member contribution, and reducing the maximum annual MTC payment to $521.43 (half of the present level), would take place with effect from 1 July 2011, being the 2011/12 MTC claim year. Most MTC claims are made after the year-end, which gives providers and Inland Revenue over 12 months to prepare for the changes before the bulk of the 2011/12 payments are made. As the proposed changes do not directly affect the claims process, the compliance costs would be expected to be relatively minimal.

77. The proposed increase to 3% for the compulsory employer contribution rate and for the default and minimum employee contribution rates would come into effect on 1 April 2013. The delayed start of this change means that it can be included within a normal taxation bill, enabling interested parties to be consulted on design aspects.

78. The proposals for a one-off enrolment exercise would be discussed with employers, payroll providers and other interested parties. This would explore both the expected costs and benefits to each party, and possible design models for such an exercise.

MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

79. Both Inland Revenue and the Government Actuary[21] currently receive and collate KiwiSaver membership and scheme data. Inland Revenue prepares regular monthly statistical reports and an annual evaluation report, which focuses largely on enrolment, contribution and incentive payments data. The Government Actuary’s report is presented to the House of Representatives pursuant to section 194 of the KiwiSaver Act 2006, and reports on the Government Actuary’s regulatory role in the management and operation of individual KiwiSaver schemes and funds, and the duties and obligations of trusts and managers in relation to those schemes. These annual reports will form the main basis for the collection and monitoring of the impacts of each KiwiSaver change over the next 12-24 months.

1 Saving in New Zealand – Issues and Options (The Treasury, September 2010).

2 Taxes are often classified according to whether income is taxed (T), taxed at a concessional rate (t) or exempt (E) at three different stages: first when income is first earned, secondly when investment returns are earned (if income is saved before it is spent), and thirdly when income is spent. New Zealand’s TTE approach means that contributions to retirement funds are made out of taxed income (T), tax is paid on investment income arising from the contributions (T) and withdrawals from retirement funds are exempt (E). Many other countries have special retirement saving vehicles that are taxed on an EET basis; so money placed in these vehicles is not taxed when first earned, nor as it compounds, but it is when it is withdrawn from the fund.

3 The SWG comprised seven independent experts in fields such as taxation law, economics and accounting from the private sector and academia, assisted by policy officials from the Treasury and Inland Revenue. It was established in August 2010, and provided its final report to the Government on 31 January 2011.

4 The Treasury, “Saving in New Zealand”, op. cit.

5 “Saving New Zealand: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Barriers to Growth and Prosperity”, Savings Working Group Final Report to the Minister of Finance, January 2011, Section 2.

6 KiwiSaver Evaluation Annual report, July 2009 – June 2010 prepared by Evaluation Services, Inland Revenue for Inland Revenue, Ministry of Economic Development, Housing New Zealand Corporation, September 2010

7 Colmar Brunton KiwiSaver Evaluation: Survey of Individuals, Final report, 21 July 2010, section 2.3.1. KiwiSaver members were asked what they would have done with their contributions if they had not put them into KiwiSaver. The estimate has been weighted by income to reflect the fact that higher income individuals who had higher rates of substitution contribute a larger proportion of funds to KiwiSaver accounts.

8 For the full text of the Statement to Parliament, see www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/statement-parliament-1.

9 Fiscal costs include both revenue foregone (ESCT exemption) and through Crown contributions to individual KiwiSaver accounts (MTC and kick-start).

10 Note that the options of lowering the maximum MTC and lowering the rate of the MTC matching payment are not additive when considered together.

11 Maximum MTC of $521.43, and matching rate of 50%. Removal of ESCT exemption

12 This also assumes a 10% fall in new and current membership.

13 MED Discussion Paper, Periodic Reporting Regulations for Retail KiwiSaver Schemes, released 01/12/2010.

14 Colmar Brunton KiwiSaver Evaluation, op. cit, page 57.

16 KiwiSaver Evaluation Report 2010, Inland Revenue Evaluation Services, for Inland Revenue, Ministry of Economic Development and Housing New Zealand Corporation, September 2010, page 12.

17 SWG: Saving New Zealand, op. cit. para 7.33.

18 http://www.retirement.org.nz/retirement-income-research/policy-review/2010-review.

19 Colmar Brunton KiwiSaver Evaluation, op. cit.

21 The Government Actuary’s functions will be moved to the Financial Markets Authority from 1 April 2011; his KiwiSaver review and reporting obligations will fall to the new Authority to discharge.