Chapter 4 - Tests

4.1 Two possible alternative approaches have been suggested – the two-outcome approach, or the three-outcome approach. The outcome of the test(s) will determine the amount of deduction owners can claim. A range of outcomes are possible under either approach, ranging from all expenditure being deductible (other than purely private expenditure) to only expenditure that relates to actual income-earning use being deductible.

4.2 This chapter evaluates the possible contents of the test(s) that determine the amount of deductions asset owners may be able to claim. The test(s) could comprise a number of different elements, from an evaluation of the owner’s subjective intentions, to objective requirements based on the actual use of the asset and the behaviour of the owner.

Possible test elements

4.3 The test(s) should correctly distinguish between and identify each category of mixed-use asset, and prescribe the correct outcome with a considerable degree of certainty, and without being overly burdensome for owners to comply with.

4.4 The test(s) could contain subjective and/or objective elements. Subjective elements attempt to ascertain the intention of the owner in relation to the asset, and objective elements look at the factual circumstances surrounding the use of the asset. An evaluation of the relative advantages and disadvantages of each element is necessary before a test can be constructed.

4.5 A wide variety of elements are possible, and any combination of these elements can make up the final test or tests. Some suggested elements include:

- whether the owner had the dominant purpose of earning income from the asset;

- the common-law business test;

- whether the asset was actively and regularly marketed as available for use at market rates;

- whether actual income-earning use or actual private use falls below or above a given threshold;

- whether private use was merely incidental or necessary to the income-earning use;

- whether private use of the asset conflicted with the income-earning use of the asset; and

- whether the incoming receipts exceeded the expenditure.

4.6 The following is an analysis of the possible elements of the proposed tests.

Whether the owner had the dominant purpose of earning assessable income from the asset

4.7 This is a subjective element that would require the owner to declare his or her intention in holding the asset. If the owner has this purpose, the owner could be given a higher amount of deductions.

4.8 The advantages of this element are:

- It may reveal the owner’s intentions in holding the asset. This is an efficient way of getting to an equitable outcome.

- It may deal appropriately with difficult situations when the asset cannot be rented out because of circumstances such as an adverse natural event. Objective tests based on actual use often fail to accommodate such circumstances.

- It is likely to be relatively easy for an owner to comply with, as the owner should know his or her own intention.

4.9 However, a purely subjective test relies heavily on the owner’s honesty, and that the owner will not falsify his or her intention in order to qualify for an outcome that allows higher deductions. This makes such rules difficult to administer and creates uncertainty for owners as they can be unsure about whether Inland Revenue will accept their stated intention.

4.10 Another issue that arises with this element is the period it would be measured over. Owners can develop intentions regarding the use of the asset on acquisition, each year, or intentions can change during the course of a year.

The common-law business test

4.11 The common-law business test contains both a subjective test and a number of useful objective tests that determine whether an income-earning activity equates to “a business”. If an owner passes the business test he or she is likely to be income-focussed and should qualify for a higher amount of deductions. The common-law business test contains the following elements:

- what the nature of the activity was;

- whether the asset was actively marketed;

- the amount of time, money and effort the person put into the activity;

- the income earned from the activity;

- whether the person runs the activity in a similar way to most businesses in the same trade; and

- whether the dominant purpose of carrying out the activities is to make a profit.

4.12 The advantage of the common-aw business test is that the test is already developed and available for application to the mixed-use asset rules. Furthermore, use of this test for mixed-use assets would align the treatment of mixed-use assets with other tax areas, so bringing the benefits of consistency. The common-law business test also evolves over time ensuring the test is always relevant.

4.13 However, there are some disadvantages associated with the business test. Firstly, it may be difficult to apply to some mixed-use assets. For instance, the rental activities of a single holiday home may never amount to “a business”. The business test is also a reasonably sophisticated and complex test to apply, requiring a number of different elements to be considered and weighed up. Consequently, the potential application of the business test could be a considerable compliance burden for owners, and is open to challenge by Inland Revenue. This is likely to create uncertainty over the level of deductions owners are able to claim.

Genuine efforts to earn income evidenced by active and regular marketing of the asset at market prices

4.14 This element would require the owner of a mixed-use asset to actively and regularly advertise the asset at a market rent, including all periods of non-use for which the asset can reasonably be used. This element attempts to determine whether the asset was genuinely available for income-earning use, and if passed the owner should be entitled to a higher level of deductions..

4.15 In general, periods during which the asset was not in use, and not actively and regularly marketed, would be a strong indication that the asset was not genuinely available for income-earning use. Furthermore, if the asset were advertised at an unreasonably high price in those non-use periods, thereby making it unlikely that anyone would rent the asset, the asset is also arguably not genuinely available for income-earning use during those periods.

4.16 An advantage of this approach is that it is a reasonably accurate way of identifying whether the asset really was available for income-earning use during periods of non-use. A further advantage is that satisfaction of this element is relatively easy to demonstrate.

4.17 However, this element also gives rise to a number of complexities including:

- What constitutes “active and regular marketing”? For example, would advertising a holiday home on a website be enough to satisfy the test?

- What constitutes a market rent?

- Advertising on its own may not necessarily be a good indication that the asset was genuinely available for use over non-use periods. For example, the owner may choose not to respond to rental enquiries for periods that the owner would like to use the asset privately.

- During what periods should the owner be required to advertise the asset? At certain times it may not be practical to use an asset for income earning purposes, for instance when repairs and maintenance are carried out, or during times of very low demand. At a minimum the asset should be advertised in periods that demonstrate a genuine income-earning purpose. For example, a ski chalet should be advertised as available for use in the ski season.

Actual income earning use or actual private use is below or above a given threshold

4.18 This objective element is known as a “bright-line” test. A bright-line test is a clearly defined rule or standard. In this context the owner of a mixed-use asset is prescribed an outcome depending upon whether the actual use of the asset is above or below a given threshold. Similar bright-line tests are used in the United Kingdom and the United States. Examples include:

- when actual income-earning use exceeds a certain number of days;

- when actual private use is less than a certain number of days; or

- when actual private use is less than a given percentage of actual income-earning use.

4.19 If one or more tests are satisfied, the owner could qualify for a higher amount of deductions. The primary advantages of bright-line tests are that they are reasonably simple to understand and comply with, and give owners some certainty over the level of deductions they are likely to be able to claim.

4.20 On the other hand, a bright-line test has dramatic marginal effects. An owner could face starkly different outcomes depending on whether their asset use was above or below the threshold. For example, if the bright-line test was set at 62 days of income-earning use, an owner who had 63 days of actual income-earning use would pass the test and qualify for a higher level of deductions. An owner who only achieved 61 days of actual income-earning use would fail the test and would receive significantly lower levels of deductions. This may be perceived as unfair, as only two days of income-earning use separate the two owners, yet they would receive completely different tax outcomes.

4.21 A bright-line test based on actual income-earning use also assumes that all mixed-use assets would achieve the income-earning threshold if the owner put in a reasonable amount of effort to rent out the asset. This could be an unreasonable assumption. For example, if the bright-line test were set at 93 days of income-earning use, the owner of a ski chalet used predominantly in the winter ski season may genuinely want to earn income from the ski chalet, but is unable to achieve 93 days rental due to a poor ski season that year. This may be perceived as an unfair outcome.

4.22 In practice, different mixed-use assets have different income-earning potential, and therefore a single bright-line test may not be suitable for every asset. However, the application of different bright-line tests for different assets would be complex and would result in difficult boundary issues.

4.23 Lastly, a bright-line test based on private use could be difficult to enforce. Receipts derived from income-earning use could easily be used to provide proof of that income-earning use. However, evidence proving the existence of private use is more difficult to obtain. Consequently, there would be some risk that owners would understate their private use of the asset in order to qualify for a more generous tax outcome.

Private use was merely incidental or necessary to the income-earning use

4.24 This element would attempt to limit private use to those days the private use was incidental to or necessary to the income-earning use. An objective test of this nature is similar to a bright-line test, based on private use. In order for an owner to qualify for generous deductions, the private use of the asset is restricted to a minimum.

4.25 An example of private use that is merely incidental or necessary to the income-earning use would be when the owner stays in his or her holiday house for a couple of days carrying out repairs and maintenance to enhance the income-earning potential of the house.

4.26 A private use restriction along these lines would clearly limit private use substantially. Consequently, the same incentives exist as with a bright-line test for owners to understate their private use of the asset, or to treat all private use as incidental or necessary to the income-earning use. Private use of this nature is arguably not private use at all. There are also definitional problems associated with this test, such as the ambiguity surrounding the term “incidental use”.

Private use of the asset did not conflict with income-earning use

4.27 This element would limit deductions for those owners whose private use of the asset conflicted with income-earning use.

4.28 This element attempts to discover the intention of the owner in holding the asset. If the private use of the asset conflicted heavily with, or took precedence over, the income-earning use, then this is a strong indication that the owner’s purpose in holding the asset is predominantly private rather than income-earning.

4.29 This element would require an analysis of the times the asset was used for private purposes, and whether that private use is likely to have conflicted with income-earning use.

Example

John owns a summer holiday home. The most popular and profitable time to rent out the home is over Christmas and New Year and John receives many offers to rent the home over this period. However, John does not accept these offers, as he wishes to reserve this time for his family and friends to enjoy.

4.30 This is an example where private use of the house clearly conflicts with the income-earning use. If this element was to form part of the test John would not be able to claim a higher level of deductions

4.31 In practice, determining what periods are the significant income-earning times may be difficult for some assets, as there may be uncertainty over when peak times start and finish. However, some basic generalisations can be made – for example, the ski season is the peak time for a ski chalet and the summer months are the peak time for beach-front holiday homes.

4.32 Furthermore, this element could create some uncertainty over when private use of the asset would conflict with income-earning use. An example would be when a holiday home has not been booked for income-earning use for a week over summer and the owners decide to use the house for their private enjoyment. However, after arriving at the house the owner is contacted requesting a booking for that week. If the owner denies the new booking and carries on with the private use of the house, would this be seen as private use conflicting with income-earning use? To cover this situation, this element may have to contain the concept of “reasonable notice”.

Whether the receipts derived from the asset exceed the expenditure

4.33 This element looks at the receipts derived from a mixed-use asset and whether they exceed out-going expenditure. If receipts are larger than the expenditure, this may indicate that the owner had an income-earning focus and therefore the owner could be allowed to claim a higher amount of deductions.

4.34 The advantage of this element is that it is simple to apply because the owner would only need to calculate whether the income raised from the asset exceeded the expenditure associated with it. The owner is already required to gather this information for income tax purposes.

4.35 The main disadvantage of this element is that different results may arise for similar or even identical assets, depending on decisions made by owners about matters such as funding or maintenance costs. For example, an owner who borrowed heavily in order to purchase a holiday house is less likely to have income exceeding expenditure compared with a lower-leveraged holiday house owner, because of the high interest costs. Furthermore, owners may be able to structure their funding between mixed-use assets and other assets they hold to ensure that income exceeds expenditure by the smallest possible amount, to maximise their claim for deductions.

4.36 Finally, this objective element does not accommodate situations when the asset is unable to achieve its full income-earning potential. This might happen if, in a particular year, expenditure on an asset exceeded the incoming receipts because it was taken off the market to undergo repairs and maintenance (which would both reduce the scope for earning income and increase expenditure).

The proposed test(s)

4.37 From the various elements above, a test or tests can be constructed that distinguish between the different possible outcomes discussed in Chapter 3, and prescribe an appropriate level of deductions. No one element would fully achieve this objective as the elements have particular advantages and disadvantages. Consequently, a combination of different elements is proposed.

Two-outcome approach

4.38 The two-outcome approach uses a single test that identifies whether an owner is income-focused and able to claim all deductions except for expenditure that is attributable to actual private use. An income-focused owner is likely to be an owner whose dominant purpose is to rent out the asset, and private use of the asset is minimal. If the owner fails the test, the owner will only be able to claim expenditure that is attributable to actual income-earning use (this is referred to as a private-focused outcome).

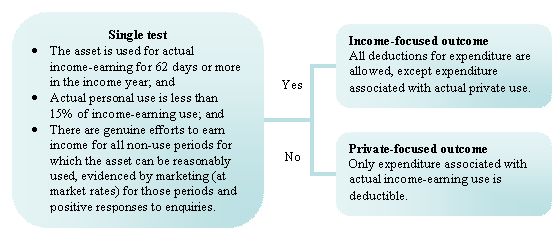

4.39 The proposed test comprises three of the elements discussed previously. The basis for including each element is discussed below. The proposed test, which would apply to each income year, is described in the following diagram:

Two-outcome approach

Income-earning use bright-line element

4.40 The test contains two bright-line elements. The first of these requires that the asset be used for actual income-earning use for 62 days or more in a year. The 62 days of income-earning use is an attempt to approximate the average income-earning potential of a range of mixed-use assets in New Zealand, for an owner was genuinely serious about earning income from that asset and made genuine efforts to that effect. For example, if an owner of a summer holiday home went to a reasonable amount of effort, and the property was genuinely attractive as a summer holiday home, it is reasonable to assume that the property could be rented for at least 62 days over the summer period.

4.41 In the context of satisfying the income-earning threshold, a day of actual income-earning use is any day the asset is used by a third party and market rates are paid.

4.42 Generally, officials consider that prescribing a reasonably significant income-earning threshold is justified given the high level of deductions an asset owner receives if they pass the test. Submissions are welcome on whether 62 days is an appropriate threshold. It should be noted, however, that the various elements in the proposed approaches should be viewed as a package. Therefore, any changes to particular elements may warrant related changes to other elements or the addition of another element.

Private use bright-line element

4.43 The second bright-line test requires that personal use is less than 15 percent of income-earning use. This threshold has been set relatively low to appropriately target the income-focused group. That is, if the owner’s dominant purpose is to rent out the asset, it is reasonable to expect that the private use of the asset will represent a low proportion of actual use. Furthermore, given the high level of deductions that owners can receive if they fall within the income-focused outcome, it is reasonable to limit private use to a low proportion of income-earning use.

4.44 In the context of satisfying the private use threshold, a day of actual private use is any day a mixed-use asset is used or is reserved for use by the owner or an associated person of the owner. This is a necessary requirement in order to prevent owners from understating their private use of the asset in order to gain higher deductions.

4.45 An issue that requires further consideration is how the use of the asset by associated persons in return for market rent should be treated. For example, an owner rents her holiday home to her brother at market rates over the summer holidays. A reasonable argument can be made for treating this period of rental as income-earning use and not private use. That is, the owner will be taxed on the rental income in the same way as if she had rented the home to a non-associated third party, and the owner is not obviously receiving a private benefit from renting the home to her brother. On the other hand, there are examples where it would be clearly inappropriate to count the period an asset is rented to an associate as income-earning days. For example, a husband rents his holiday home to his wife for market rent.

4.46 This is a difficult area and submissions are welcome on an approach that reflects these concerns but is still able to be applied with a reasonable degree of certainty.

Active and regular marketing

4.47 The final element of the test is that the owner must have gone to genuine efforts to earn income for all non-use periods for which the asset can be reasonably used. This should be evidenced by marketing for those periods and a positive engagement with enquiries. This element is essential as an owner is unlikely to have the dominant purpose of earning income from an asset if the owner did not advertise the asset.

4.48 The term “reasonable” has been used in this element as an acknowledgment that it is unreasonable to require owners to advertise the asset in all non-use periods, as in certain circumstances the asset may not practically be able to be used for income-earning purposes. For example, it would not be reasonable for an owner to seek to rent out a yacht for a period when the yacht has been taken out of the water for de-fouling.

Three-outcome approach

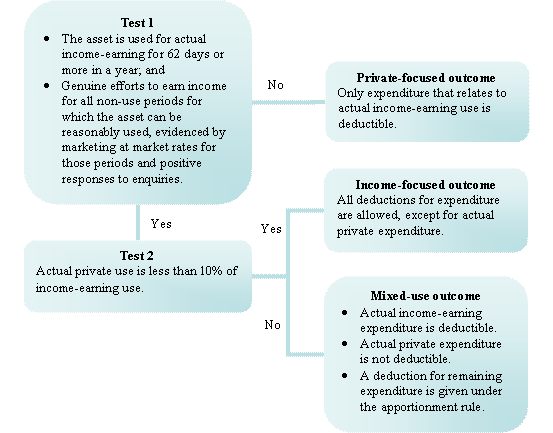

4.49 The three-outcome approach requires two tests. The first test identifies assets where the focus is on private use, and the second test distinguishes between assets where the focus is on earning income and those which are genuine mixed-use assets. The proposed two tests are as follows:

Three-outcome approach

Test 1

4.50 Test 1 contains two elements. The first is a bright-line element, setting a minimum level of income-earning use at 62 days in a year. The second element requires that the owner make genuine efforts to earn income for all non-use periods for which the asset can be reasonably used, evidenced by marketing for those periods and positive responses to enquiries. If the owner does not satisfy either element, the private-focused outcome will apply.

4.51 These elements are also features of the two-outcome approach and, the same advantages and disadvantages apply. In addition, the definition of an actual income-earning use day would be the same.

Test 2

4.52 If the use of the asset successfully meets the first test, the owner is required to apply the second test. The second test determines whether the income-focused or mixed-use outcome should apply. This test contains one bright-line element that limits private use to less than 10 percent of income-earning use. If the asset passes this test (and also passes all the elements in test 1) the asset will be subject to the income-focused outcome. If this test is failed the asset is treated as a genuine mixed-use asset and expenditure for non-use periods is apportioned (the apportionment formula is explained in Chapter 3).

4.53 The second test is intentionally a difficult test to satisfy. This test should capture only those assets used predominantly for income-earning purposes and therefore attracting the highest amount of deductions. However, it is acknowledged that many income-focused assets may still have a small amount of private use – often associated with the income-earning use. Consequently test 2 allows a small amount of private use.

Proposed test(s) summary

4.54 The primary objective of the three-outcome approach is similar to the two-outcome approach – namely, simplicity and certainty. However, the three-outcome approach recognises that some assets may be used for genuine mixed-use purposes and therefore their owners should be able to apportion the expenditure incurred that relates to periods the asset is not used.

Application of proposals – The Johnston family example

4.55 The Johnston family owns a holiday home in the Coromandel. In the 2013 tax year the family actively marketed the house at market rates in newspapers and on internet sites. The house was rented out for 95 days in that year. The Johnston family also used the holiday home themselves for fourteen days over seven weekends during the year.

4.56 The Johnston family incurred a total of $10,000 of expenses in that year. These expenses can be split into three amounts:

- $2,500 – directly attributable to the income-earning use of the house.

- $500 – directly attributable to the family’s private use of the house.

- $7,000 – attributable to the time when the house was empty.

4.57 The total amount of expenses that the Johnston family will be able to claim will depend upon whether the two-outcome or the three-outcome model is applied.

Two-outcome approach

4.58 Under the two-outcome approach, the family will satisfy the test, as outlined in the following table:

| Elements of the test | Pass or fail |

|---|---|

| The asset is used for actual income-earning use for more than 62 days in the income year. | Pass – the asset was used for actual income-earning for 95 days in the year. |

| Actual personal use is less than 15% of income-earning use. | Pass – the asset was used for private purposes for fourteen days in the year (private use was 14.74% of income-earning use). |

| There are genuine efforts to earn income for all non-use periods for which the asset can be reasonably used, evidenced by marketing (at market rates) for those periods and positive responses to enquiries. | Pass – the family actively marketed the asset. |

4.59 Since the family satisfies all the elements in the test, the family is able to claim both the $2,500 of expenses that was directly attributable to the income-earning use of the house, and the $7,000 of expenses that was attributable to the time when the house was empty – totalling $9,500 of allowable deductions.

4.60 However, if the family had chosen to use the holiday home for another weekend, raising their private use to sixteen days, the family would not satisfy the test (private use would be 16.84% of income-earning use). In this situation, the family would only be able to claim the $2,500 of expenses that was directly attributable to the income-earning use of the house.

Three-outcome approach

4.61 Under the three-outcome approach the family will satisfy the first test and fail the second test, as outlined in the table below:

| Elements of the two tests | Pass or fail |

|---|---|

| Test 1 | |

| The asset is used for actual income-earning use for more than 62 days in the income year. | Pass – the asset was used for actual income-earning for 95 days in a year. |

| There are genuine efforts to earn income for all non-use periods for which the asset can be reasonably used, evidenced by marketing (at market rates) for those periods and positive responses to enquiries. | Pass – the family actively marketed the asset. |

| Test 2 | |

| Actual private use is less than 10% of income-earning use. | Fail – the asset was used for private purpose for fourteen days in a year (private use was 14.74% of income-earning use). |

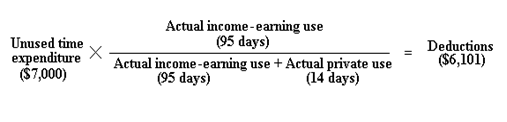

4.62 Since the family satisfies the first test and fails the second test, the family will be able to claim the $2,500 of expenses that was directly attributable to the income-earning use of the house, and apportion the $7,000 of expenses attributable to the time when the house was empty using the apportionment formula:

4.63 Under the formula, the family is able to claim $6,101 of the total expenses attributable to the time when the house was empty. Therefore, the family is able to claim $2,500 of direct expenses plus $6,101 of apportioned expenses equalling total allowable deductions of $8,601.

Submission points

- Are there any more useful and relevant elements within the tests that should be considered?

- Do the suggested tests represent a significant compliance burden?

- Do the suggested tests produce equitable outcomes?

- Is the 62-day income-earning use threshold achievable for the majority of mixed-use assets?

- Is a single bright-line threshold based on the average income-earning potential of a number of different mixed-use asset (62 days), supported by other elements, preferable to a number of different bright-line thresholds for different types of mixed-use asset, without any supporting elements?

- Bright-line tests based on income-earning and private use are relatively simple to apply and offer certainty. However, they can lead to arbitrary results. Would a more complex test that accommodates extenuating circumstance be a better approach and, if so, what should the test(s) look like?

- How should the use of the asset by an associated person in return for market rent be treated – private use or income-related use?

- Overall, which approach is preferred?