RIA 3 - Ring-fencing rental losses

| Date | 1 August 2018 |

|---|---|

| Type | Regulatory impact assessment |

| Title | Ring-fencing rental losses |

| Downloads | |

| Contents |

Coversheet: Ring-fencing rental losses

| Advising agencies | The Treasury and Inland Revenue |

|---|---|

| Decision sought | Agreement to key design features of a rental loss ring-fencing policy |

| Proposing Ministers | Hon Grant Robertson (Minister of Finance) and Hon Stuart Nash (Minister of Revenue) |

SUMMARY: PROBLEM AND PROPOSED APPROACH

Problem Definition

What problem or opportunity does this proposal seek to address? Why is Government intervention required?

The Government’s stated objective for ring-fencing rental losses is to reduce unfairness by levelling the playing field between property speculators/investors and owner-occupiers. Currently, investors can have part of the cost of servicing their mortgages subsidised by the reduced tax on their other income sources, helping them to outbid owner-occupiers for properties.

Proposed Approach

How will Government intervention work to bring about the desired change? How is this the best option?

Ring-fencing rental losses reduces the tax benefits enjoyed by property investors who buy property in anticipation of capital gain.

SECTION B: SUMMARY IMPACTS: BENEFITS AND COSTS

Who are the main expected beneficiaries and what is the nature of the expected benefit?

Key beneficiaries are expected to be:

- First-home buyers. Ring-fencing of rental losses could help improve first home buyers’ ability to compete with investors, improving housing affordability for home buyers, and potentially increasing the share of New Zealanders who own their own homes; and

- Government. Ring-fencing of rental losses is expected to increase tax revenue by approximately $190 million per annum.

Where do the costs fall?

Costs are expected to fall on:

- Investors. Residential property investors who negatively gear could face higher tax liabilities on an ongoing basis, if they persistently make a loss. It could be the case that investors start experiencing positive rental cash flows after a period. Inland Revenue estimates that approximately 40 percent of taxpayers with rentals record rental losses at any given time, with an average estimated annual tax benefit of $2,000; and

- Renters. Rental loss ring-fencing will reduce after tax rental returns for some landlords. This could encourage the transfer of housing stock from investment housing (ie, rental housing) to owner-occupier housing, putting pressure on the remaining rental stock. On average, owner-occupied housing tends to have fewer people per house. This suggests that the transfer of housing stock from rental to owner-occupied may reduce the amount of housing available for each remaining renter unless there is an adequate flow of new housing onto the rental market. This may lead to increased rents. Landlords may also pass on their rental losses to tenants in the form of increased rents. There are other ways that this and other policies could impact the rental market, and officials note that there is significant uncertainty about the net impact.

What are the likely risks and unintended impacts, how significant are they and how will they be minimised or mitigated?

Key risks and unintended impacts include:

- Uncertainty around the impact on the housing market. The Government is closely monitoring the performance of the housing market. However, given the number of other policy and regulatory changes to the housing market, it may not be possible to isolate the impact of this proposal on the housing market.

- Implementation risks for Inland Revenue. Changes will be required to START (Inland Revenue’s tax processing computer system). A detailed assessment of required changes and an execution plan is being made as part of returns planning for the 2019-20 income year.

Identify any significant incompatibility with the Government’s ‘Expectations for the design of regulatory systems’.

There is no incompatibility between this regulatory proposal and the Government’s ‘Expectations for the design of regulatory systems’.

SECTION C: EVIDENCE CERTAINTY AND QUALITY ASSURANCE

Agency rating of evidence certainty?

Evidence supporting housing market impact analysis is limited, and suggests significant uncertainty as to the net impacts of the policy, especially on the rental market.

Fiscal impact estimates have been modelled using Inland Revenue data on negatively-geared rental properties. Significant simplifying assumptions have been made, on which the fiscal estimates are conditional.

To be completed by quality assurers:

Quality Assurance Reviewing Agency:

Inland Revenue

Quality Assurance Assessment:

The Quality Assurance reviewer at Inland Revenue has reviewed the Ring-fencing rental losses RIA prepared by the Treasury and Inland Revenue and considers that the information and analysis summarised in it partially meets the quality assurance criteria.

Reviewer Comments and Recommendations:

The RIA describes how ring-fencing rental losses will meet the stated objective and also provides excellent coverage of the main uncertainties and risks around its likely impact.

The analysis summarised in the RIA is as good as could be expected in light of the constrained range of options considered and the uncertainties over the net impacts of loss ring-fencing on the housing market. Even so, the analysis only partially meets the quality assurance criteria primarily because it is not possible to be confident that the stated objective is being met in the best way and with the least unintended consequences.

Impact Statement: Ring-fencing rental losses

SECTION 1: GENERAL INFORMATION

Purpose

1.1.1 The Treasury and Inland Revenue are solely responsible for the analysis and advice set out in this Regulatory Impact Assessment, except as otherwise explicitly indicated. This analysis and advice has been produced for the purpose of informing key policy decisions to be taken by Cabinet.

Key Limitations or Constraints on Analysis

1.1.2 The key limitations and constraints applying to this analysis are as follows:

a) Constrained range of options considered: The Government has already announced its intention to introduce ring-fencing of rental losses. Options considered are therefore focussed on key design settings for that policy, rather than consideration of alternatives to loss ring-fencing.

b) Time constraints: Ministers have decided to plan for the introduction of loss ring-fencing rules for the 2019-20 tax year. With that commencement date in mind, the proposals are required to be included in legislation introduced before the start of the 2019-20 income year to give taxpayers a degree of certainty about how the rules will operate.

c) Lack of empirical data: The analysis on the impact of this policy on the housing market is constrained by a lack of empirical data. There are few recent examples of countries implementing loss ring-fencing rules. In cases where such rules have been introduced (for example, in Australia in the 1980s), it has been difficult to tease out the effects of loss ring-fencing rules on observed changes in the housing market. When empirical evidence is not available, a theoretical assessment of the expected impact has been provided.

d) Assumptions underpinning impact analysis: Ring-fencing of rental losses is estimated to increase tax revenue by approximately $190m per annum once fully implemented. The primary caveat to this revenue forecast is that it assumes static behaviour. A change towards greater equity investment in rental housing, or a change away from investment in residential rental properties altogether, could displace revenue from other taxable investments. This impact is not captured in the revenue forecast.

Responsible Manager:

Peter Frawley

Policy Manager

Policy & Strategy

Inland Revenue

1 August 2018

SECTION 2: PROBLEM DEFINITION AND OBJECTIVES

2.1 What is the context within which action is proposed?

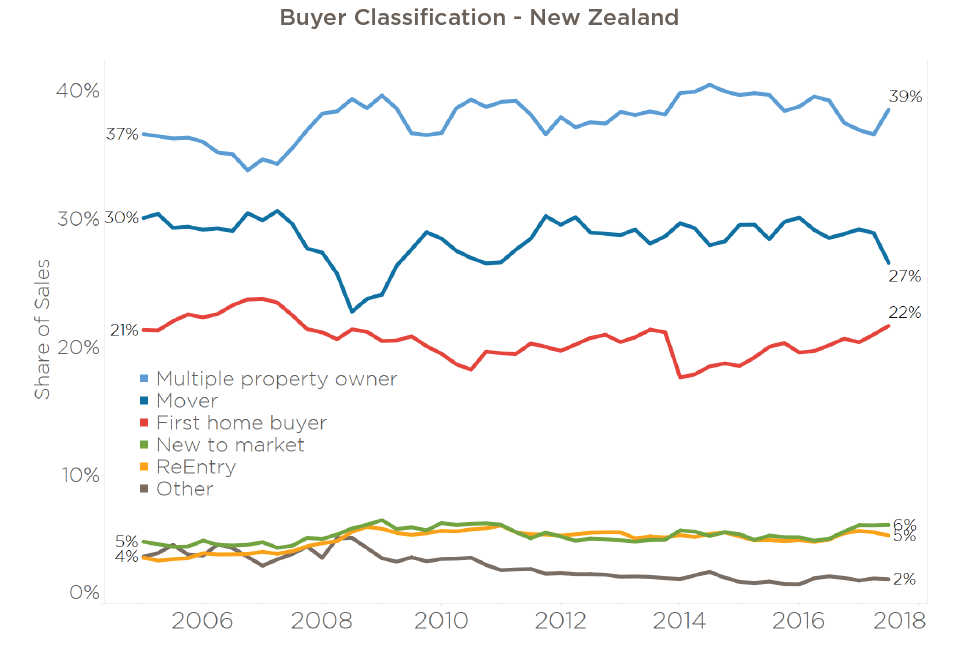

2.1.1 First home buyers account for 22% of home purchases in New Zealand, compared with 39% for multiple property owners. This may suggest that first home buyers can struggle to compete against investors and existing owner-occupiers in the market. Home ownership rates have now fallen to 63% - down from 74% in 1991.[1]

Source: CoreLogic NZ

2.1.2 Speculative capital gain is a likely driver for investor activity in the residential housing market. The average return on rental property excluding capital gains is low – the average gross rental yield on a three-bedroom Auckland property is 3% per annum.[2] This suggests investors are buying property in anticipation of capital gain. Other possible drivers for investor activity include the prospect of future increases in rents, or because it is perceived as safer than other types of investments.

2.1.3 Falling rates of home ownership, untaxed capital gains, and increasing house prices contribute to equity concerns around housing, and there is strong interest in measures to improve housing affordability, especially for first home buyers.

2.1.4 In this context, negative gearing has come under scrutiny. Negative gearing involves investors reducing their taxable income with rental losses. The practice is relatively widespread in the New Zealand rental market – 40% of taxpayers with residential investment property report rental losses, with an average tax benefit of $2,000 per annum.

2.1.5 We expect the practice of negative gearing of rental properties to continue if no further action is taken. The magnitude of losses being claimed is likely to be dependent on changes in the housing market (for example, increases in rents will tend to reduce rental losses, all other things being equal), and interest rates.

2.1.6 Many overseas countries have some form of loss ring-fencing of residential property, including the United Kingdom and the United States.

2.2 What regulatory system, or systems, are already in place?

2.2.1 Investment housing is currently taxed under the same rules that generally apply to other investments. This means that rents are income, and interest and other expenses (other than capital improvements) are deductible. Any capital gain realised on sale of the property is not taxed unless the property is held on revenue account. Revenue account land holders are predominantly dealers, developers, and people who acquire properties for resale (though there are a number of other rules that may mean a property is on revenue account, including the bright-line test, which taxes sales of residential properties within a defined time period). Most rental property investors hold their property on capital account and are not subject to tax on the capital gain.

2.2.2 Currently, investors (including those who hold their property on capital account and are not subject to tax on the capital gain) can use losses from the rental properties to offset their income from other sources, thus reducing their income tax liability.

2.3 What is the policy problem or opportunity?

2.3.1 The policy problem is that there is an uneven playing field between property investors who are buying property in anticipation of capital gain, and owner-occupiers. Currently, investors can have part of the cost of servicing their mortgages subsidised by the reduced tax on other sources of income, helping them to outbid owner-occupiers (whose mortgages are not tax-deductible) for properties.

2.3.2 Rental housing is not formally tax favoured. However, there is an argument that it may be under-taxed compared to other asset classes given that tax-free capital gains are often realised when rental properties are sold. The fact that rental property investors often make persistent tax losses is a possible indication that expected capital gains are an important motivation for many investors purchasing rental property. While interest and other expenses are fully deductible, in the absence of a comprehensive capital gains tax, not all of the economic income generated from rental housing is subject to tax. There is therefore an argument that, to the extent deductible expenses in the long-term exceed income from rents, those expenses in fact relate to the capital gain, so should not be deductible unless the capital gain is taxed. It is reasonable to suppose that there is a widespread perception of unfairness, especially in the context of falling rates of home ownership, untaxed capital gains, and increasing house prices (see above in section 2.1).

2.4 Are there any constraints on the scope for decision making?

2.4.1 The Government has committed to implementing loss ring-fencing. Officials have therefore only considered options as to different broad approaches to ring-fencing, and have not considered alternatives to loss ring-fencing.

2.4.2 The Government has also established the Tax Working Group (the TWG) to look at the structure, fairness and balance of the tax system. The TWG’s Terms of Reference include a requirement that particular consideration be given to “[w]hether a system of taxing capital gains or land (not applying to the family home or the land under it), or other housing tax measures, would improve the tax system.”[3] Because consideration of a capital gains tax is within the purview of the TWG, it is not considered here as a possible option for addressing the issue that underlies the concern about investors who buy property in anticipation of capital gain having an unfair advantage over owner-occupiers – which is that not all of the economic income generated from rental housing is subject to tax. If a comprehensive capital gains tax were to be implemented, there could be a case for reconsidering whether rental loss ring-fencing is necessary. We note that the Government has stated that any significant changes legislated for from the TWG’s final report will not come into force until the 2021 tax year.[4]

2.4.3 There are a range of Government policies and initiatives concerning housing. Supply-side initiatives include KiwiBuild, Special Housing Areas, and infrastructure financing and funding efforts. Demand side initiatives include extension of the bright-line test, restrictions on foreign buyers, and the Reserve Bank’s loan-to-value ratio loan restrictions.

2.5 What do stakeholders think?

2.5.1 Prior to releasing an officials’ issues paper for consultation, officials had initial discussions on the proposal with a number of key private sector advisors, including tax professionals and the New Zealand Property Investors’ Federation. Those discussions were aimed at gathering private sector views on key design issues and potential implementation and compliance concerns.

2.5.2 An officials’ issues paper Rental loss ring-fencing was released in March 2018 for full public consultation on key design issues. Inland Revenue received 106 submissions in response to this issues paper. Submitters’ views on the design options are noted in the discussion of those options in section 5.

SECTION 3: OPTIONS IDENTIFICATION

3.1 What options are available to address the problem?

3.1.1 Our options analysis looks at the following packages of key design options for the proposed loss ring-fencing rules:

Option 1: Status quo.

Option 2: Design options proposed in the officials’ issues paper.

Option 3: Design options reflecting submissions received on the officials’ issues paper.

3.1.2 The options considered in relation to each of the above key design issues are as follows: (all options are mutually exclusive)

Option 1: Status quo

3.1.3 There are no rules which ring-fence rental losses, therefore any losses incurred on a rental property can be offset against the taxpayer’s other income.

Option 2: Design options proposed in the officials’ issues paper

3.1.4 This option reflects the package of design features which were proposed in the officials’ issues paper released for public consultation in March 2018.

Land within the scope of the proposed rules

3.1.5 The proposed loss ring-fencing rules are to apply to residential land. There is already a definition of “residential land” in the Income Tax Act 2007, and the loss ring-fencing rules would apply to land within that definition. Using the definition already in the legislation would avoid the additional complexity of having different definitions for different rules. The options for what property the rules should apply to are around what residential land should be excluded from the scope of the rules.

3.1.6 The rules are not proposed to apply to residential land that is the taxpayer’s main home, or residential land that is subject to the mixed-use asset rules.

3.1.7 The rules will not apply to residential land that is on revenue account because the taxpayer acquires the property for the purpose of a land-related business.[5]

3.1.8 Finally, the rules will apply to residential land that is owned by all persons, including companies and trusts.

Level at which the loss ring-fencing rules should apply (ie, at the individual property level or across a portfolio)

3.1.9 Losses are ring-fenced within a portfolio of residential property. If a taxpayer has a portfolio of residential investment properties, losses from one property can be used to offset profits from another property within the portfolio.

Whether ring-fenced losses should be released on the sale of a residential property

3.1.10 Ring-fenced losses are able to be used on a sale of residential land that gives rise to taxable income; to the extent they reduce the taxable gain to nil, with any further unused losses remaining ring-fenced.

What rules should be put in place to minimise opportunities to structure around the loss ring-fencing rules

3.1.11 This option would include specific rules to address a structuring opportunity to get around the new rules. These concern interest allocation and the interposing of entities.

3.1.12 There will be specific rules to ensure that interposed entities cannot be used to circumvent the loss ring-fencing rules.

3.1.13 There should not be any specific rules for allocating a taxpayer’s interest expenditure as between ring-fenced residential property and other assets.

Option 3: Design options reflecting submissions received on the officials’ issues paper

Land within the scope of the proposed rules

3.1.14 In addition to the design features in Option 2 for property within the scope of the proposed rules, three further exclusions are proposed.

3.1.15 All land that will definitely be subject to tax on sale will be excluded from these rules.

3.1.16 The rules will not apply to widely-held companies, because any residential land they hold is assumed to be incidental to their business.

3.1.17 The rules also will not apply to accommodation provided to employees or other workers where it is necessary to provide that accommodation due to the nature or remoteness of the business.

Level at which the loss ring-fencing rules should apply (ie, at the individual property level or across a portfolio)

3.1.18 While the rules will generally apply on a portfolio basis, taxpayers will also be able to elect to apply the rules on a property-by-property basis if they wish, so if a property is taxed on sale any remaining losses for that property can be released and used to offset against other income. If such an election is not made, then the rules will continue to apply on a portfolio basis.

Using ring-fenced losses

3.1.19 Ring-fenced losses should be able to be transferred between companies in a wholly-owned group with rental income. It is not proposed that ring-fenced losses should be able to be carried back.

3.1.20 The usual shareholder continuity rules which apply to the use of losses by companies under the general corporate tax rules will continue to apply to ring-fenced losses. Losses should not be released and available to offset against other income if shareholder continuity is breached.

Whether ring-fenced losses should be released on the sale of a residential property

3.1.21 There is no change from Option 2 for this design feature. Ring-fenced losses are able to be used on a sale of residential land that gives rise to taxable income, but only to the extent those losses reduce the taxable income to nil.

What rules should be put in place to minimise opportunities to structure around the loss ring-fencing rules

3.1.22 There is no change from Option 2 for this design feature. There will be specific rules to ensure that interposed entities cannot be used to circumvent the loss ring-fencing rules, but no specific interest allocation rules.

3.2 What criteria, in addition to monetary costs and benefits, have been used to assess the likely impacts of the options under consideration?

3.2.1 The generic tax policy process (GTPP) includes a framework for assessing key policy elements and trade-offs of proposals. This framework is consistent with the Government’s vision for the tax and social policy system, and is captured by the following criteria:

- Efficiency and neutrality – the tax system should bias economic decisions as little as possible;

- Fairness and equity – similar taxpayers in similar circumstances should be treated in a similar way;

- Efficiency of compliance – compliance costs for taxpayers should be minimised as far as possible; and

- Efficiency of administration – administrative costs for Inland Revenue should be minimised as far as possible.

3.2.2 Efficiency and fairness are the most important criteria. It is generally worth trading-off increased compliance costs or administration costs for gains in these two criteria.

3.3 What other options have been ruled out of scope, or not considered, and why?

3.3.1 As noted at section 2.4, because consideration of a capital gains tax is within the purview of the TWG, it is not considered here as a possible option for addressing the concern that investors who buy property in anticipation of capital gain, and who are able to deduct expenses, have an unfair advantage over owner-occupiers – which is that not all of the economic income generated from rental housing is subject to tax.

3.3.2 Therefore, options considered are focussed on key design settings for loss ring-fencing, rather than consideration of alternatives to loss ring-fencing.

SECTION 4: IMPACT ANALYSIS

Marginal impact: How does each of the options identified at section 3.1 compare with the counterfactual, under each of the criteria set out in section 3.2?

| Option 1 Status quo |

Option 2 Design options proposed in the officials’ issues paper |

Option 3 Design options reflecting submissions received on the officials’ issues paper |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency and Neutrality | 0 | - The proposals would treat residential investment property differently to other investments. |

- This option introduces further exclusions from the rules in appropriate circumstances. |

| Fairness and equity | 0 | ++ This option helps even the playing field between investors and owner-occupiers. |

++ This option more accurately targets property investors. |

| Efficiency of compliance | 0 | - This option would have required people other than property investors to apply new ring-fencing rules. |

0 This option decreases compliance costs for people other than property investors compared to option 2 by excluding them from the new rules. |

| Efficiency of administration | 0 | 0 There would need to be relatively minor changes to some Inland Revenue forms and systems. |

0 The design features from this option would impose no significant additional administration costs compared to Option 2. |

| Overall assessment | 0 | + As the objective was to increase the fairness and equity of the tax system, this consideration outweighs the other considerations and overall we think this option is an improvement over the status quo. |

+ As with Option 2, fairness and equity outweigh the other considerations. This option is an improvement over Option 2 with respect to the other considerations and is therefore the preferred option. |

Key:

++ much better than doing nothing/the status quo

+ better than doing nothing/the status quo

0 about the same as doing nothing/the status quo

- worse than doing nothing/the status quo

- - much worse than doing nothing/the status quo

SECTION 5: CONCLUSIONS

5.1 What option, or combination of options, is likely best to address the problem, meet the policy objectives and deliver the highest net benefits?

5.1.1 Officials consider the preferred option is Option 3: Design options reflecting submissions received on the officials’ issues paper. The reasons this option is the preferred approach are discussed below.

Land within the scope of the proposed ring-fencing rules

5.1.2 As noted above, the proposed loss ring-fencing rules are to apply to residential land as already defined in the Income Tax Act 2007. For the reasons discussed below, we consider that the main home, mixed-use land, certain revenue account land, land owned by widely-held companies, and employee and farming accommodation should be excluded from the scope of the rules, and that land owned by companies and trusts should not be excluded.

5.1.3 It is noted that all of this option is generally neutral as compared to the status quo (no change from the current rules), because all of these options are around what land should be outside the scope of the proposed loss ring-fencing rules – which means the current treatment would remain applicable.

Main home

5.1.4 As noted above, the concern the proposed ring-fencing rules are aimed at addressing is the uneven playing field between property speculators/investors and owner-occupiers. This is because rental losses can be used by investors to reduce their tax on income from other sources – effectively subsidising part of the cost of their mortgages, and helping them to outbid owner-occupiers for properties.

5.1.5 The focus of the proposed rules is on loss-making rental properties, so it is recommended that a taxpayer’s main home be specifically excluded from the scope of the rules. Submitters on the officials’ issues paper have indicated that they agreed with this approach.

5.1.6 While part of someone’s main home may be rented out, and this activity could generate a loss, it is not considered that such a situation contributes to an uneven playing field between investors who buy property in anticipation of capital gain and owner-occupiers.

5.1.7 We suggest that the concept of a “main home” mirror that used for the purposes of the bright-line test – which would mean that a person can have only one main home, and that to qualify for the exclusion the property has to be used predominantly as the person’s main home. However, we suggest one difference from the bright-line main home exclusion, in that a qualifying property should be used predominantly as the person’s main home for most of the income year in question, rather than for most of the time the person owns the property (which is the case for the bright-line main home exclusion). This makes more sense in the context of loss ring-fencing, as the focus is not on the length of ownership, but on the use of the property.

Mixed-use land

5.1.8 The existing definition of “residential land” would also include holiday houses that are sometimes used privately and sometimes rented out. Many such properties would be subject to the mixed-use asset rules.

5.1.9 The mixed-use asset rules provide for the apportionment of expenditure. Notwithstanding the apportionment formula, a tax loss can still arise for a mixed-use asset. This is more likely to occur when the income-earning use of the asset is low. Therefore, the mixed-use assets rules quarantine (or ring-fence) losses where there is low income-earning use of an asset. Under the quarantining rules, a person who is in an occasional loss position will not be able to offset their loss against other income in the current year, but will be able to use it against their future profits from the mixed-use asset. However, a person who is in perpetual loss will never have future profits to offset the losses against, and will therefore not be able to utilise them.

5.1.10 Property subject to the mixed-use asset rules should be scoped out of the ring-fencing rules, because the mixed-use asset rules will cover most if not all mixed-use asset losses.

Certain revenue account land

5.1.11 We suggest that the ring-fencing rules should not apply to taxpayers who hold land on revenue account because they are in a land-related business.[6] Taxpayers in certain businesses relating to land hold their land on revenue account, so the profits on sale will be taxed. This applies to people in the business of dealing in land, developing land, dividing land into lots, or erecting buildings. At balance date, such taxpayers may have a number of properties on hand, though they may not be currently rented out. The policy rationale for loss ring fencing in these situations is weakened as the capital gains are already taxed. Submitters did not think the loss ring-fencing rules should apply to such taxpayers, as this could discourage new developments, which would be a barrier to increasing housing supply.

5.1.12 As discussed below, we suggest that rental losses are able to be used against taxable land sales to the extent they reduce the taxable gain to nil, with any further unused losses remaining ring-fenced to future rental income or taxable gains on other land sales. While developers, dealers, etc, may have losses in respect of properties on hand at balance date, those losses being able to be used against income from other sales or rental activity in the year would mean that their businesses would be unlikely to be disadvantaged by the ring-fencing rules. In most cases the income from their sale or rental activity would be expected to exceed their losses.

5.1.13 However, in any overall loss-making year, we do not consider it necessary to ring-fence losses for these taxpayers. This would enable those taxpayers to use losses arising in any year against other income – for example within their consolidated group (as they are likely to be companies). There is not the same concern in relation to these taxpayers about any of their deductible expenses relating to untaxed gains, as all of their land is on revenue account.

5.1.14 In addition to the exclusions for revenue account land described in Option 2, submitters commented that all land that will definitely be subject to tax on sale should be excluded from these rules. This includes for example, land that was bought with the intention of resale or land that had been subject to more than minor development or division work within 10 years of acquisition. We recommend that if land is identified to Inland Revenue as being on revenue account not subject to any contingencies (for example, being sold within a particular time period), that land should be considered to be definitely subject to tax and excluded from the scope of the ring-fencing rules, as all of the economic income will be subject to tax.

Land owned by companies and trusts

5.1.15 Some private sector advisers and submitters on the issues paper suggested that the ring-fencing rules should apply only to individuals (ie, natural persons) and look-through companies, and not to other companies or trusts. It was noted that company losses are effectively ring-fenced inside the company, as are losses in a trust. It was also noted that the rules would apply to some large companies (for example, large power companies that hold some residential rental property), imposing compliance costs on those companies, in circumstances that were unlikely to be the target of the reform.

5.1.16 While there is some argument that losses are ring-fenced within a company, so there is no need for the rules to apply to companies, officials do not consider that additional compliance costs for some large corporates would justify rules that apply only to individual taxpayers. This would leave open the possibility of holding rental properties in a company, trading trust, or family trust, and offsetting rental losses against other income. Limiting the ring-fencing rules to individuals would, therefore, significantly undermine the fairness of the rules. We therefore do not recommend this option.

Land owned by widely-held companies

5.1.17 The design features in Option 2 included within the scope of the proposed ring-fencing rules all land held by trusts and companies, including land owned by widely-held companies. A number of submitters on the officials’ issues paper commented that applying the ring-fencing rules would create substantial compliance costs for large companies which are not the target of the proposal. It was noted that large companies often hold residential land incidentally to their business (for example as sites for future development, or for employee accommodation). In these circumstances, the mischief of offsetting property losses against labour or other income with the hope of capital gains from the properties is not present. For that reason we recommend that widely-held companies be excluded from the scope of the rules.

Employee and farming accommodation

5.1.18 The design features in Option 2 did not carve out land used to provide accommodation to employees, or as part of their farming business. A number of submitters have suggested that these should be carved out of the ring-fencing rules. Submitters considered that such properties have no connection to the mischief the ring-fencing rules are seeking to address, and including them would create compliance costs without any corresponding benefit.

5.1.19 We agree that it would not undermine the rules to exclude accommodation provided to employees (or other workers, as will often be the case in farming) where it is necessary to provide that accommodation due to the nature or remoteness of the business. In such situations the perceived mischief of offsetting property losses against labour or other income with the hope of capital gains from the properties is not present. We therefore recommend such an exclusion.

Level of ring-fencing

5.1.20 The proposed loss ring-fencing rules could be applied either on a property-by-property basis or on a portfolio basis. A portfolio approach would mean that investors could offset losses from one rental property against rental income from other properties, calculating their profit/loss on their overall portfolio. This may be seen as less equitable than a property-by-property approach, in that it may favour wealthier taxpayers with larger property holdings. A property-by-property basis would mean that each property is looked at separately, so losses on one cannot offset income from another.

5.1.21 A property-by-property approach could, in theory, be more effective in reducing tax benefits to investors. In practice, however, a property-by-property approach could result in de facto portfolio outcomes. Taxpayers could potentially rebalance their debt funding to avoid having loss-making properties, or at least minimise the extent to which any particular property is loss-making.

5.1.22 This taxpayer response would be inefficient, and may also mean that, in terms of the objective, a property-by-property approach may have no real advantage over a portfolio approach – adding complexity and increasing compliance costs for no gain.

5.1.23 Further, a property-by-property approach may be seen as unfair in that if a taxpayer has two properties and breaks even on the portfolio overall, the taxpayer’s tax position would depend on whether they break even on both properties or make a gain on one and a loss on the other.

5.1.24 Applying the rules on a portfolio basis would be significantly simpler than a property-by-property approach, from a compliance and administrative point of view, as this is how rental income is currently returned. The additional compliance costs a property-by-property approach would create, especially for investors holding many properties, was highlighted by private sector advisors.

5.1.25 We have looked at the approach to loss ring-fencing in other jurisdictions, and have not found any that apply an asset-by-asset approach. Typically, such rules are applied on a portfolio basis, or investments within particular categories are pooled (for example, in the United States, where ring-fencing applies to “passive activity” losses). However, a property-by-property approach could arguably be more aligned to addressing concerns that large-scale investors who own multiple rentals are able to use losses on new acquisitions to continually reduce their tax.

5.1.26 Most submitters on the officials’ issues paper supported the rules applying on a portfolio basis, as it would be easier from a compliance point of view. However, some submitted that a portfolio approach penalises smaller “mum and dad” investors and favours investors with large portfolios.

5.1.27 Some submitters also suggested that taxpayers should be able to make an upfront election to apply the rules on a property-by-property basis if they wish. If a property is taxed on sale any remaining losses for that property could then be released. Officials do not see any issue with taxpayers electing to apply the rules on a property-by-property basis if they are willing to bear any associated compliance costs in order to be able to close out the net profit on that property. It is noted that some submitters advised they (or their advisors) already do this, so they did not see this as adding compliance costs for them. This option is desirable for taxpayers if it means any remaining losses after the taxable sale of a property can be released to be used against other income. We are recommending that be the case – this is discussed further in 5.1.41.

5.1.28 For the above reasons, we suggest that the ring-fencing rules generally apply on a portfolio basis, so a person with multiple properties would calculate their overall profit or loss across their whole residential portfolio. However, we also recommend that taxpayers who wish to elect to apply the rules on a property-by-property basis should be allowed to do so.

Using ring-fenced losses

Grouping losses

5.1.29 In addition to the design features in Option 2, it has been submitted that losses should be able to be transferred between companies under the grouping rules. Often a corporate group will hold rental properties in a different entity to trading business properties.

5.1.30 We agree that ring-fenced losses should be able to be transferred between companies, but that this should be limited to companies in the same wholly-owned group, as the economic ownership is the same in that situation. It is acknowledged that this would be a higher threshold than is applied for the grouping of other losses.

5.1.31 Transferred losses should remain ring-fenced, so they are only able to be used in the relevant income year to the extent the transferee company has residential rental income or residential land sale income, with any remaining losses being carried forward and remaining ring-fenced.

Carrying back ring-fenced losses

5.1.32 Some submitters suggested that losses should be able to be carried back as a typically profit-making property may make a loss in one year due, for example, to large repairs and maintenance expenses or a period of vacancy.

5.1.33 We do not recommend that losses be able to be carried back. This would add complexity, and if a property is typically profit-making the carried forward losses would be available to offset against income in future years. Allowing losses to be carried back would also be inconsistent with general policy settings.

Shareholder continuity

5.1.34 It has been submitted that companies could have losses ring-fenced when their overall position is tax paying, and that this would be unfair. It has been suggested either that the 49% shareholder continuity requirement should not apply to ring-fenced rental losses, or failing that, that if shareholder continuity is breached, losses should be made available to offset against other income.

5.1.35 The shareholder continuity rules reflect that it should be the shareholders at the time company losses arise who are able to benefit from them in the future.

5.1.36 We consider that it would undermine the credibility and fairness of the loss ring-fencing rules if ring-fenced rental losses were not subject to the shareholder continuity requirement, or if losses were released when continuity is breached.

Release of losses on sale

5.1.37 In the case of a property with ring-fenced rental losses that is taxed under one of the land sale rules on disposal, there is an argument that the losses should be able to be fully utilised (ie, un-fenced) at that point, and be used to offset any other income of the taxpayer. This would reflect that all of the economic income from the investment has been taxed (the rental stream and the capital gain), and that the investor should not be penalised for making an overall loss on the investment. For this reason, not releasing losses that relate to a particular property on a taxable sale of that property would undermine neutrality and fairness.

5.1.38 However, if the rules are applied on a portfolio basis (which is the preferred option – see 5.1.21 to 5.1.27), allowing accumulated rental losses to give rise to a tax loss on a disposal subject to one of the land sale rules would create risks. For example, it would enable a portfolio investor to sell a property that has made a small capital gain within the bright-line period, offset that gain with ring-fenced losses from across their portfolio, and apply any remaining losses from the portfolio against other income. While there are ring-fencing rules in relation to the bright-line test, they only apply to deductions for the cost of the property, not other costs.

5.1.39 Enabling taxpayers to sell their lowest capital gain makers within the bright-line period and access what might be substantial portfolio-wide accumulated ring-fenced losses would significantly undermine the credibility of the rules.

5.1.40 Release on taxable sale, recognising that the full economic income had been taxed, would be the preferred option if the ring-fencing rules were to apply on a property-by-property basis. This is because it would only be losses that relate to the particular property that would be released. As noted at 5.1.21, a portfolio approach is preferred to a property-by-property approach because it would be significantly simpler from a compliance and administrative point of view. However, as also noted at 5.1.27, we are recommending that taxpayers who wish to elect to apply the rules on a property-by-property basis be able to do so. For those properties, we think that the preferred option of fully releasing the ring-fenced losses should be adopted. This design feature would be in addition to the features identified in Option A. The new design feature of allowing an election to apply the rules on a property-by-property approach enables all the losses associated with a given property to be used against that property upon a taxable sale.

5.1.41 We therefore do not consider that ring-fenced losses should generally be fully released on a taxable sale of residential property, meaning the losses (if not exhausted from offsetting the income derived on sale) would be able to be used to offset other income. However, for those properties which have had the rules applied to them on a property-by-property basis on the taxpayer’s election, we recommend that the losses become fully unfenced if they are taxed upon sale. This would also be the case where the rules applied on a portfolio basis and all of the properties in a portfolio were sold and taxed. This would most commonly be the case for land that was taxable under the bright-line test because it was sold within five years of acquisition.

5.1.42 We do not recommend that losses become released on any sale of residential land if there was no tax on the sale of that property. Releasing losses on a non-taxable disposal would reduce the impact of ring-fencing to one of timing alone, which would reduce the effectiveness of the measure.

Anti-structuring rules

5.1.43 There are two main structuring opportunities that have been considered in terms of whether specific rules are required. These concern interest allocation and the interposing of entities.

Specific interest allocation rules

5.1.44 Without specific interest allocation rules, investors (particularly larger and more sophisticated investors) may be able to structure around the loss ring-fencing rules. For example, by reorganising funding so that business assets other than rental properties are debt-funded, and rental properties are equity-funded, to the greatest extent possible. This could undermine the credibility of the rules, neutrality, and fairness.

5.1.45 However, interest allocation rules would add substantial complexity, and increase compliance and administrative costs. Because money is fungible, it is very difficult to attempt to match borrowings to particular investments (tracing). Stacking rules (eg, allocating debt firstly to ring-fenced investments) may be seen as unfair. And pro rata interest allocation between assets that are subject to the ring-fencing rules and those that are not would require regular valuation of assets.

5.1.46 If interest on any loan that was secured by a residential property was included in the rules, this would create issues for many taxpayers who use their rental properties to secure loans for their businesses. This would impact on small and medium business’ access to capital. In addition, many arrangements could be even more difficult to apply interest allocation rules to, as revolving credit facilities are often used to fund both a rental property and a business.

5.1.47 The private sector advisors who officials consulted were strongly of the view that the substantial complexity that interest allocation rules would add should be avoided. It was observed that such complex rules would be particularly onerous for smaller taxpayers to comply with.

5.1.48 Given the substantial complexity that interest allocation rules would introduce, we recommend against such rules. The ring-fencing rules will affect many taxpayers, with varying levels of sophistication and tax knowledge, and we consider it important that they remain as easy to apply as possible, and minimise compliance costs for taxpayers.

Specific rules for interposed entities

5.1.49 We have considered whether there should be specific rules to mitigate the risk of taxpayers interposing entities to get around the loss ring-fencing rules.

5.1.50 Without rules to deal with interposed entities, a simple way taxpayers (particularly larger and more sophisticated taxpayers) could get around ring-fencing rules would be by interposing an entity (eg, a company) to separate a loan (and interest deduction) from the residential rental property, so the interest is not subject to ring-fencing. This could undermine the credibility of the rules, neutrality, and fairness.

5.1.51 In the 1980s, New Zealand had a loss restriction provision that capped the extent to which losses from rental, agricultural and horticultural activities could be offset against other income (the maximum was $10,000 per annum). There was also a provision that clawed back interest and development expenditure where land was sold within ten years of acquisition and the profit derived on sale was not otherwise assessable. A major failing of the interest claw back provision was the absence of specific rules to deal with simple structuring such as that noted above. As a result, a common strategy was to hold the land in a company and incur interest on funds borrowed to buy shares in the company. This meant that no interest was incurred with respect to the land, so there could be no clawback of interest deductions on sale.[7]

5.1.52 While there is a general anti-avoidance rule in the Income Tax Act, it may not be adequate to prevent the simple interposing of an entity to get around loss ring-fencing, as there are legitimate non-tax reasons for holding property in an entity. In addition, it is preferable from a certainty perspective to have specific rules to counter avoidance concerns rather than rely on the uncertain boundary inherent in the general anti-avoidance rule. There would be some administrative costs associated with a specific rule to deal with interposed entities, as compliance would need to be monitored. However, compared to relying on the general anti-avoidance rule, this approach should reduce taxpayer compliance costs, uncertainty, and administrative costs.

5.1.53 We therefore recommend a specific rule to deal with the interposing of entities, as this would otherwise be a simple mechanism to get around the loss ring-fencing rules, and would undermine their credibility.

5.1.54 The private sector advisors who officials consulted were in agreement that rules to deal with the above mechanism of interposing an entity should be developed, to maintain the integrity of the ring-fencing rules.

5.1.55 The officials’ issues paper consulted on a suggested approach to dealing with interposed entities. Submitters have proposed a number of technical refinements to the treatment of interposed entities proposed in Option 2, which we agree with. These are:

- The 50% “residential property land-rich” threshold should take into account all residential properties, not just those within the scope of the ring-fencing rules. This is to ensure that the interposed entity rule applies even if the main home was held in the same entity as a rental property (which would often be worth less than the main home). We recommend that the rule therefore apply where over 50% of the entity’s assets are residential properties, not just residential properties within the scope of the ring-fencing rules.

- Interest deductions for the owner of a “residential property land-rich” entity should not be ring-fenced to the extent the profit from the residential property or properties is sufficient to cover the interest, but is not distributed. This is appropriate as the properties are profitable overall, so there is no mischief in allowing the interest covered by the profits to be deducted in that year.

- Where part of an entity’s capital is used to acquire a rental property, and part is applied to something else, the interest incurred by the shareholder to fund the entity’s capital should be allocated on a pro-rata basis between the uses to which the capital is applied.

- Where the entity’s capital is used to acquire a rental property, and the entity also has another profitable activity that does not require any (or much) capital, the shareholder’s interest expenses should only be allocated to the extent of the entity’s profit from the rental activity.

5.2 Summary table of costs and benefits of the preferred approach

| Affected parties | Comment: | Impact | Evidence certainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additional costs of proposed approach, compared to taking no action | |||

| Investors | Residential property investors who negatively gear will face higher tax liabilities for as long as they are making losses on their investment. Inland Revenue estimates that approximately 40% of taxpayers with rental properties record rental losses, with an average estimated tax benefit of $2,000 per annum. |

$570m total over 5-year forecast period (not discounted), assuming full application from 2019-20 income year.[8] And then $190m/yr ongoing. |

High |

| Owner-occupiers | Current home owners will be negatively impacted insofar as the policy puts downwards pressure on house prices. | Low | Low |

| Renters | Loss ring-fencing will reduce after tax rental returns for some landlords. This could encourage the transfer of housing stock from investment housing (ie, rental housing) to owner-occupier housing, putting pressure on the remaining rental stock. Reduced supply of rental housing could put upwards pressure on rental prices. | Medium | Low |

| Inland Revenue | Initial Inland Revenue estimates suggest implementation costs will be up to $1.5 million, mostly through changes to START (Inland Revenue’s new tax processing computer system). | Up to $1.5m (not discounted) |

High |

| Wider government | Pressures in the rental market could increase fiscal costs to the Government, most directly from higher income-related rent subsidy costs. | Medium | Low |

| Total Monetised Cost | $570m over 5 year forecasting period (not discounted). And then $190m/yr ongoing. |

High | |

| Non-monetised costs | Medium | Low | |

| Expected benefits of proposed approach, compared to taking no action | |||

| Owner-occupiers | Negative gearing restrictions could help improve first home buyers’ ability to compete with investors, improving housing affordability for home buyers, and increasing the share of New Zealanders who own their own homes. Residential property investors who negatively gear properties will face higher tax liabilities under the proposal. This will weaken the business case for their residential property investments, and constrain investor cash flows, both of which will lead to reduced demand for residential property by those investors. All else being equal, this should improve affordability (ie, reduced house prices) for first home buyers. |

Medium | Low |

| Renters | Lower house prices could put downwards pressure on rents, potentially offsetting the pressures on the rental market noted in “Additional costs” section above. | Low | Low |

| Wider government | Ring-fencing rental losses will prevent investors from offsetting their non-property earnings with rental losses, thereby increasing tax revenues. | $570m total over 5-year forecast period (not discounted), assuming full application from 2019-20 income year. And then $190m/yr ongoing. |

High |

| Total Monetised Benefit | $570m over 5 year forecasting period (not discounted) | High | |

| Non-monetised benefits | Medium | Low | |

5.3 What other impacts is this approach likely to have?

Uncertainty about housing market impacts

5.3.1 There is significant uncertainty about the net impact of the policy on the housing market, especially on the rental market. Overseas experience underlines the uncertainty in the direction and magnitude of housing market impacts. For example, negative gearing was banned in Australia between 1985 and 1987, and while rents spiked in Sydney during this period, they were flat or falling across much of the rest of the country. The exact relationship between the tax changes and observed changes in rent is unclear.

5.4 Is the preferred option compatible with the Government’s ‘Expectations for the design of regulatory systems’?

5.4.1 Yes.

SECTION 6: IMPLEMENTATION AND OPERATION

6.1 How will the new arrangements work in practice?

Legislative process

6.1.1 Following consultation and final decisions on the design of the proposed rules, primary legislation will be prepared to give effect to loss ring-fencing.

6.1.2 It is currently anticipated that loss ring-fencing rules will take effect from the 2019-20 income year. It is planned that legislation will be introduced before the start[9] of the income year the rules will apply from (the 2019-20 income year) – giving most taxpayers a degree of certainty about how the rules will operate.

Implementation options

6.1.3 The rules could either apply in full from the outset, or alternatively they could be phased in over three years (ie, a third of a taxpayer’s losses are ring-fenced in year one, then two-thirds of their losses in year two). Tax law changes are not usually phased in, but this possible approach has been suggested to allow affected investors more time to adjust to the new rules, or to rearrange their affairs before the rules apply in full. However, we note that phased introduction of the rules would result in some additional complexity.

6.1.4 The officials’ issues paper sought feedback on whether the rules should apply in full from the 2019-20 income year, or be phased in over two or three years. Submitters were strongly in favour of phasing the rules in over three years.

6.1.5 A number of submitters considered that existing rental properties should be grandparented, on the basis that such a fundamental change to the rules after investments have been made would be unfair. Other submitters suggested that the rules should apply in full for properties acquired after an announced date, but phased in for existing properties (or existing properties grandparented). Officials consider that these suggestions would produce overly complex rules, and recommend that the rules either apply in full from the outset, or be phased in for all properties over three years.

6.1.6 On balance however, Inland Revenue considers that phasing in the changes could potentially create a precedent-setting risk and there is a stronger argument to apply the rules in full from the 2019-20 income year for all properties.

6.1.7 The Treasury prefers a split approach, with no phasing for new investments, and a three-year phase in for existing investments. This is on the basis that investments made after the ring-fencing rules have been introduced do not need time to adjust to the new rules, while acknowledging that some time may be necessary for existing investments.

6.1.8 The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment have expressed a preference for a phased introduction for both existing and new investments. This is because if there are sales of some low quality rental properties in anticipation of the Healthy Homes Guarantee Act standards, as expected, a phased introduction of the loss ring-fencing rules could strengthen incentives for new owners to upgrade these rental properties quickly.

Responsibility for ongoing operation and enforcement

6.1.1 Once implemented, Inland Revenue will be responsible for ongoing operation and enforcement of the new rules.

Communications

6.1.2 When introduced to Parliament, commentary would be released explaining the new rules, and further explanation of the effect would be contained in a Tax Information Bulletin, which would be released shortly after the bill receives Royal assent. The information on Inland Revenue’s website, booklets, etc, would be updated to explain the new rules to property investors.

6.2 What are the implementation risks?

6.2.1 Inland Revenue is currently delivering on its Business Transformation programme. It is anticipated that implementation of ring-fencing of rental losses will occur in START, as the proposed commencement date of 2019-20 occurs after the go-live of START major release 3 scheduled for April 2019. Implementation of the proposed rules will mean changes to START will be required. Officials expect these changes to be relatively minor. However, they are not yet fully scoped, costed and integrated into Inland Revenue’s 2019-20 annual returns plan, creating an implementation risk.

6.2.2 Successful implementation is based on taxpayers understanding the changes and how they apply to their situation. For those electing to apply the rules on a property-by-property basis, this explaining the changes in a simple way for them to understand may present an implementation risk.

SECTION 7: MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

7.1 How will the impact of the new arrangements be monitored?

7.1.1 Inland Revenue’s monitoring, evaluation and review of new legislation takes place under the Generic Tax Policy Process (GTPP). The GTPP is a multi-stage tax policy process that has been used to design tax policy in New Zealand since 1995.

7.1.2 The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment currently investigates trends in house prices and housing affordability, using a variety of measures to get a complete picture of affordability. For home buyers, this includes the level of house prices, how house prices compare to incomes, and the experimental Housing Affordability Measure for first home buyers. For renters, the data monitored includes rent levels and the Housing Affordability Measure for renters. The impact of loss ring-fencing may be seen in an improvement in measures of housing affordability for home purchasers, and may also be seen in the proportion of houses in each area that are purchased by first home buyers and investors – with the percentage of property purchased by first home buyers expected to increase over time as a result of the ring-fencing rules. The impact on rental affordability will be monitored to identify if there appear to be any significant negative impacts on renters from the policy. There is significant uncertainty about the scale of the potential impact of the policy on the housing market. Furthermore, because of the substantial number of factors that affect the housing market, including other policy interventions under development, it is likely to be difficult from a practical perspective to identify the causal impact of the proposed loss ring-fencing rules on affordability for first-home buyers, though housing affordability data may give some indication of the impact of the policy.

7.1.3 We will also monitor data on the amount of ring-fenced rental losses, which will provide an indication of the impact of the policy, and whether the proposed anti-structuring rules are effective.

7.2 When and how will the new arrangements be reviewed?

7.2.1 We will monitor the first year of operation of new legislation, and if we identify anything that suggests a formal review is warranted we will undertake that – for example data that suggests significant negative impacts on the rental housing market. Stakeholders will have the ability to raise concerns with us, and if there is a need to make remedial amendments to the new rules these will be prioritised for inclusion on the Tax Policy Work Programme, and proposed amendments would go through the GTPP.

7.2.2 It is noted that if a comprehensive capital gains tax were to be implemented, loss ring-fencing would be reviewed at that time.

[1] https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/dwelling-and-household-estimates-december-2017-quarter

[2] https://www.barfoot.co.nz/market-reports/2017/december/changes-in-gross-yield

[3] https://taxworkinggroup.govt.nz/terms-of-reference/

[4] https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/towards-fairer-tax-system-tax-working-group-terms-reference-announced

[5] And in the case of a business of erecting buildings, the taxpayer or an associated person made improvements to the land.

[6] As per section CB 7 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

[7] Consultative Document on the Taxation of Income from Capital (December 1989).