Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) – update on the New Zealand work programme

May 2016

Office of the Minister of Revenue

Cabinet

BASE EROSION AND PROFIT SHIFTING (BEPS) – UPDATE ON THE NEW ZEALAND WORK PROGRAMME

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. Since late 2012, there has been significant global media and political concern about evidence suggesting that some multinationals pay little or no tax anywhere in the world. This problem is referred to as base erosion and profit shifting or “BEPS”.

2. This paper sets out for your information background to the OECD/G20 BEPS project, the related OECD/G20 initiative regarding a global Standard for Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information in Tax Matters (in short, Automatic Exchange of Information, or AEOI) and New Zealand’s response to the OECD/G20 recommendations. In particular the paper covers:

a. the broad principle underpinning New Zealand’s taxation of multinationals;

b. what BEPS and AEOI are;

c. what the G20 and OECD propose we should do about BEPS and AEOI;

d. what New Zealand has done, and plans to do, to address BEPS issues and AEOI; and

e. whether implementing the initiatives in the BEPS Action Plan mean New Zealand can better tax multinationals.

PRINCIPLE UNDERPINNING NEW ZEALAND’S TAXATION OF MULTINATIONALS

3. All taxable income earned in New Zealand should have tax paid in New Zealand.

4. In determining taxable income:

a. all gross revenue earned in New Zealand should be identified and reported; and

b. deductions from gross revenue should reflect the real economic costs of production, free of measures deliberately designed to reduce tax liability.

5. BEPS tax planning strategies can undermine this principle.

What is BEPS?

6. Media attention around multinational tax avoidance has focussed particularly on technology companies, such as Apple, Google and Amazon, whose digital business model has made possible to structure their business to pay very little tax anywhere in the world. However, other multinationals with more traditional business models have also faced criticism for avoiding tax.

7. The wide range of international tax planning techniques that are used to achieve such results are collectively referred to BEPS tax planning strategies.

8. BEPS tax planning strategies exploit gaps and mismatches in countries’ domestic tax rules to make profits disappear for tax purposes or to shift profits to locations where there is little or no real activity but the taxes are low, resulting in little or no overall corporate tax being paid.

9. Other BEPS tax planning strategies take advantage of current international tax rules that are still grounded in a bricks and mortar economic environment rather than today’s environment of global players which is characterised by the increasing importance of intellectual property and the digital environment.

10. For these reasons it is difficult for any single country acting alone to fully address the issue. BEPS is a global problem which requires a global solution. Co-ordination is key.

What is AEOI?

11. A related, but different, issue is the ability of taxpayers to hide assets offshore to evade tax obligations in their home jurisdictions. This is facilitated by the current lack of transparency and exchange of information in the global tax system.

12. AEOI is a multilateral initiative aimed at countering this problem, recovering tax revenue lost to non-compliant taxpayers, and further strengthening transparency in tax matters.

13. The initiative would see financial institutions in participating jurisdictions gather financial information on foreign taxpayers within that jurisdiction under a “common reporting standard” (CRS). This information would be passed to the tax authority in that jurisdiction, who would exchange that information with the tax authority in the taxpayer’s ‘home’ jurisdiction.

14. International expectations are that participating jurisdictions complete first exchanges of information by 30 September 2018 at the latest. New Zealand is aiming to meet this timeframe (CAB-16-MIN-0034 refers).

What do the G20 and OECD propose we do about BEPS and AEOI?

15. There is a strong political impetus to address BEPS and improve transparency of tax information. However, the G20 and OECD emphasise that this is a global problem that requires a co-ordinated global solution.

16. The concern a global approach addresses is that if it is left for individual countries to implement ad-hoc domestic legislation it could actually make the problem worse (as asymmetry between different countries’ tax laws are part of the existing problem) or potentially cripple businesses who would face double or triple taxation as governments scramble to protect their own tax bases.

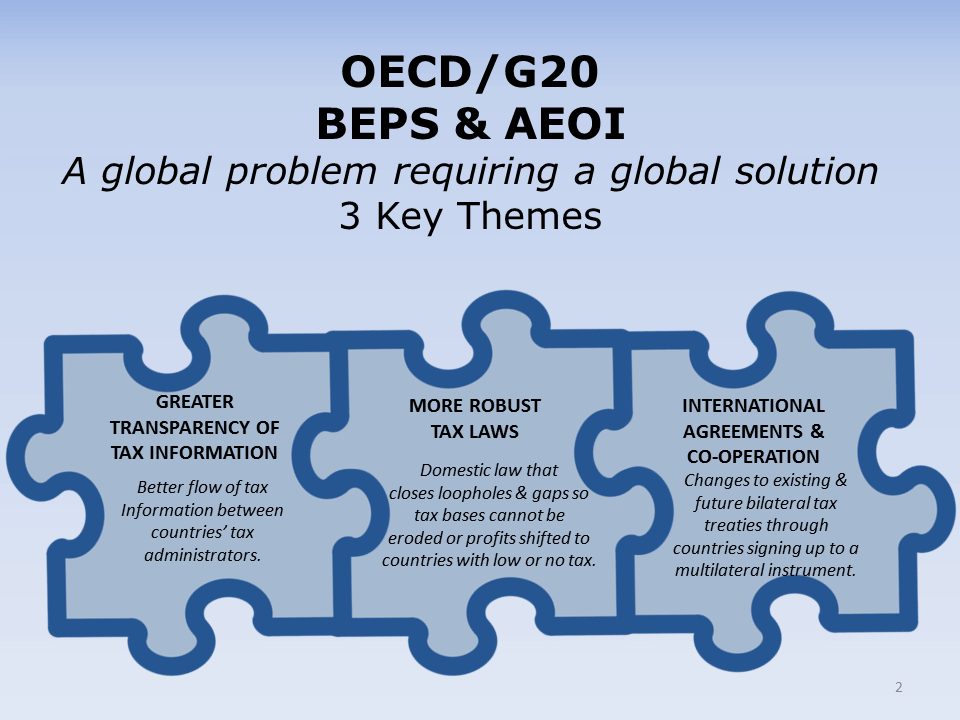

17. The G20 and OECD released the final reports on a 15 point Action Plan to address BEPS concerns last October and a global standard to facilitate AEOI in 2013. These initiatives can be grouped under three broad themes:

a. more robust tax laws;

b. international agreements and co-operation; and

c. greater transparency of tax information.

18. This is illustrated in slide 1 in the attachment to this paper.

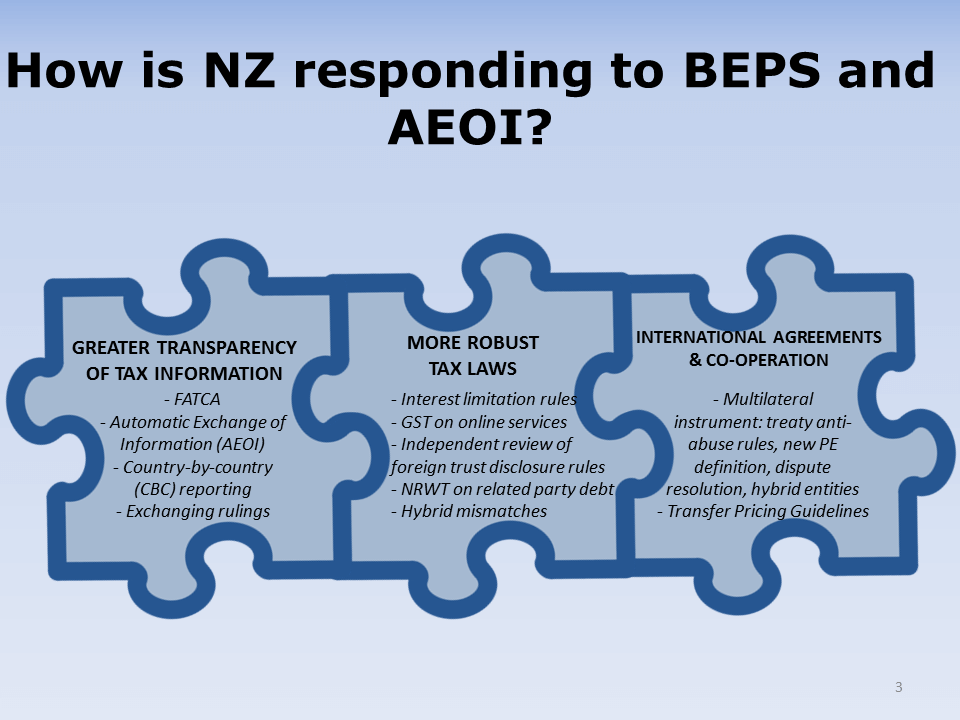

19. Each country needs to focus on these areas to ensure the international tax system as a whole is robust and fit for purpose. The New Zealand initiatives are described below and illustrated in slide 2 in the attachment to this paper.

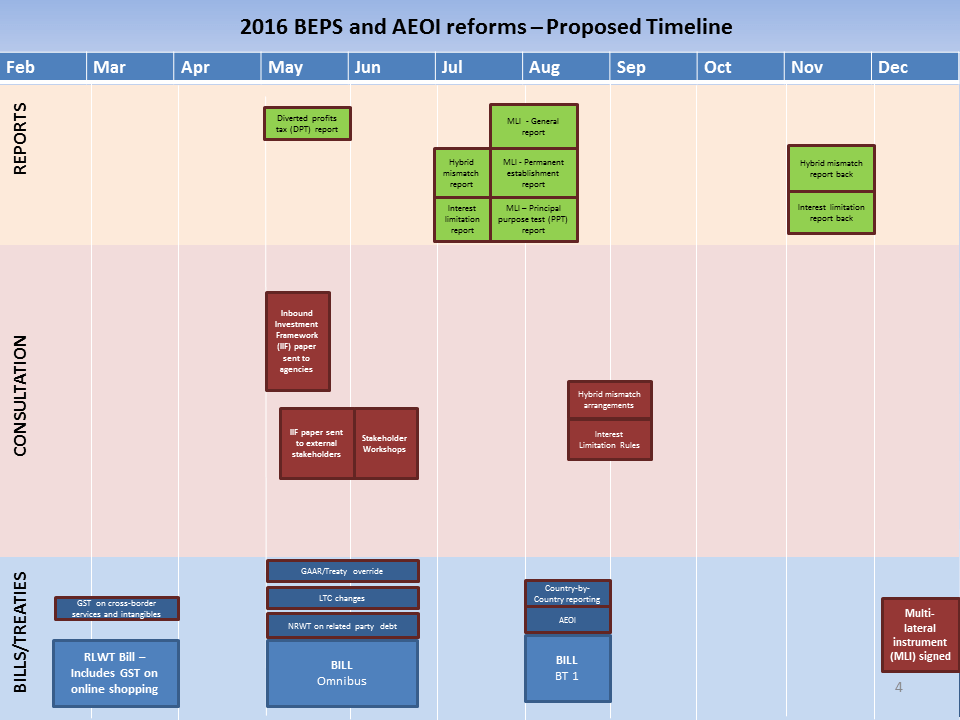

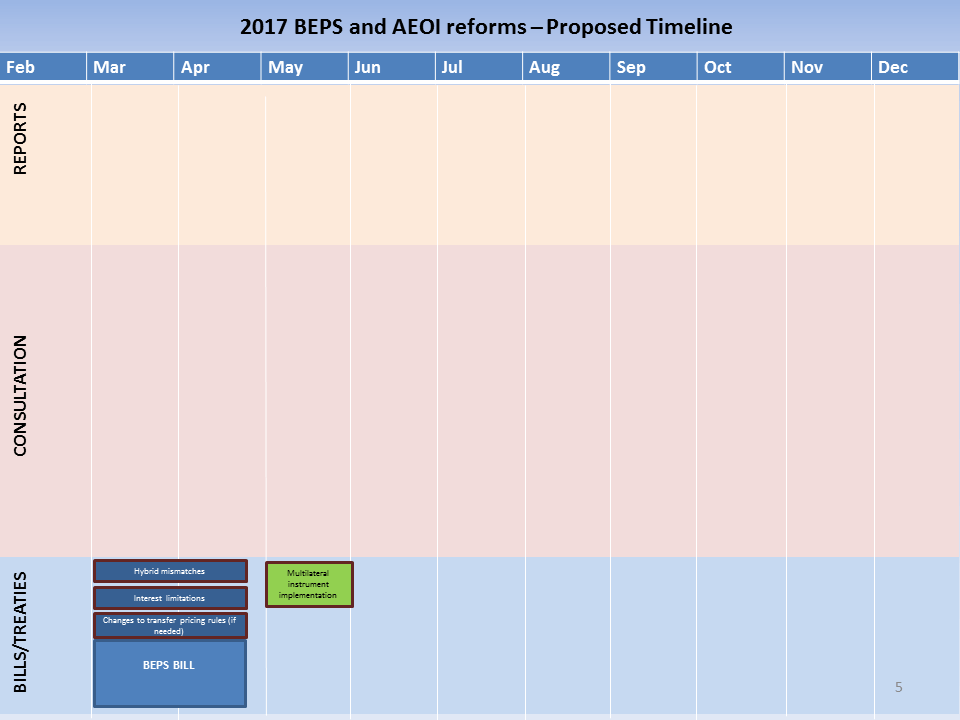

20. The timeline on slides 3 and 4 in the attachment to his paper shows the proposed dates for delivery of the New Zealand BEPS, AEOI and related measures.

What is New Zealand doing to address BEPS and AEOI?

21. The New Zealand tax system is already quite robust by international standards, so a few of the recommendations in the Action Plan do not require New Zealand to make any changes.

22. For example, New Zealand already has controlled foreign company (CFC) rules that meet the standards recommended by the OECD in the final report on Action 3 - Designing Effective Controlled Foreign Company Rules. These are rules which prevent New Zealand residents avoiding tax on the profits of their offshore companies. Similarly, New Zealand does not have any changes it needs make to domestic tax law to address Action 5 – Harmful Tax Practices. This was confirmed by the OECD in 2012 ([Confidential OECD report number withheld]).

23. There are a number of initiatives New Zealand has either already implemented or will implement to address the three key BEPS themes.

More robust tax laws

24. First, we need to ensure our own domestic tax laws are robust and consistent with international best practice. This is to ensure that our domestic tax settings protect our tax base and do not facilitate double non-taxation, tax avoidance or evasion. In this area, New Zealand:

a. has already strengthened its CFC rules and thin capitalisation rules (by reducing the level of debt a New Zealand entity controlled by non-residents can have before interest deductions will be disallowed and widening the application of the rules to include more foreign ownership structures);

b. has also introduced the bank minimum equity rules, the re-characterisation of stapled stock provision, removed the foreign dividend exemption for deductible foreign equity and eliminated the conduit regime;

c. introduced a Bill in November 2015 that imposes GST on online services consumed in New Zealand – this legislation will apply to transactions from 1 October 2016;

d. has recently introduced a Bill that:

i. strengthens the non-resident withholding tax and approved issuer levy rules to ensure these taxes apply consistently across economically equivalent transactions consistent with the existing policy intent;

ii. confirms that the general anti-avoidance rule overrides double tax agreements; and

iii. limits the use of look-through companies as conduit vehicles by non- residents (especially to earn foreign income);

e. aims to consult on hybrid mismatch rules in the second half of this year which would prevent companies structuring their business entities or financing arrangements to take advantage of differences in how countries’ tax these arrangement. Legislation could then be introduced in March 2017;

f. aims to consult later this year on interest limitation rules which would prevent companies stripping excessive profits out of New Zealand by way of deductible interest payments. Legislation could then be introduced in March 2017;

g. is undertaking an inquiry into foreign trust disclosure rules to ensure they are fit for purpose;

h. may consider whether other measures to help address BEPS concerns (for example, officials will shortly report on the diverted profits tax adopted by the United Kingdom and Australia and possibly proposals on increased public transparency of information about the tax paid by multinationals in New Zealand);

i. already has robust CFC rules; and

j. does not have harmful tax practices as identified by the OECD in their last review

in 2012.

International agreements and co-operation

25. Second, we need to work with the OECD and treaty partners to ensure international agreements are fit for purpose. New Zealand:

a. signed the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters in 2012. This became operative for New Zealand on 1 January 2015 and is also an essential element of New Zealand’s overall transparency framework;

b. will sign up to the OECD’s multilateral instrument which will be open for signatures by 31 December. This instrument will amend countries’ network of tax treaties to insert a new anti-treaty abuse article, a new permanent establishment definition, anti-hybrid entity rules and dispute resolution articles; and

c. will apply revised OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines to address misallocation of profits to low tax jurisdictions. Legislation could be introduced to facilitate this (if needed) in March 2017.

Greater transparency of tax information

26. Third, we need to improve the transparency of tax information so that people cannot hide wealth and avoid their tax obligations. This requires Inland Revenue to collect relevant information about companies and individuals operating in New Zealand and exchange that information with other jurisdictions’ tax administrations. To this end, New Zealand:

a. has introduced an International Questionnaire to monitor profit shifting activities of major foreign-owned groups of companies;

b. implemented measures to comply with the United States (US) foreign account tax compliance act (FATCA) which requires the collection and exchange of information from financial institutions about investments by US citizens (from 1 April 2015);

c. will introduce legislation in mid-2016 to enable automatic exchange of information (AEOI) with a wide range of countries’ tax administrations about the financial affairs of their residents (from September 2018);

d. is already starting to exchange Inland Revenue’s taxpayer binding ruling information with foreign tax administrators;

e. is introducing legislation to require our multinational companies to prepare country-by-country (CBC) reports (these reports basically provide a breakdown of business activities of the multinational group across the world and financial information for each country in which they operate) in line with the OECD proposal.

New Zealand’s current administrative measures to address BEPS

27. While there are a number of measures New Zealand is working on in conjunction with the OECD, it is important to note that New Zealand already has strong administrative practices in terms of scrutinising the activities of multinationals operating here.

28. Inland Revenue has an extensive international compliance programme addressing profit shifting, in particular transfer pricing of goods and services and international financing arrangements. The main focus is the Significant Enterprises segment of the population, comprising 558 taxpayer groups with turnover in excess of $80m per annum and representing almost 60% of the corporate tax base. Key performance data (including tax payments, operating margins and interest expenditure) are monitored closely with expert assistance from fulltime in-house specialists on transfer pricing and financial arrangements (known as Principal Advisors).

29. The Top 50 taxpayer groups receive comprehensive coverage, being account managed on a one-to-one basis. All other Significant Enterprises are required to submit annually a basic compliance package (BCP) comprising a group structure, financial statements and tax reconciliations which are then examined closely. Depending on the risk rating from the review of the BCP, past history and other intelligence, further review or an in-depth audit may follow. Inland Revenue supplemented the BCP with International Questionnaires in 2015 and 2016 to specifically cover BEPS issues for 292 foreign-owned groups.

30. Advance pricing agreements (APAs) have proven extremely useful as a robust up-front means of dealing with profit shifting risk, especially the more complex issues that arise. APAs represent a more co-operative approach to tax compliance as opposed to adversarial audits. Multinationals that complete an APA are required to submit annual reports and supporting evidence to confirm adherence to the agreed terms and conditions. As at 31 December 2015, 139 APAs had been completed successfully by Inland Revenue.

Will implementing the initiatives in the BEPS Action Plan mean New Zealand can better tax multinationals?

31. Yes – to the extent the multinationals have a “permanent establishment” (generally a physical presence in New Zealand through which they carry on business) and they are currently using profit shifting techniques to move profits out of New Zealand, such as:

a. excessive interest payments to related parties;

b. inflated royalty payments (or other such fees); or

c. financial instruments or entities that exploit arbitrage opportunities between the

New Zealand tax rules and those of other countries.

32. The BEPS Action Plan will also crack down on the use of tax treaties to facilitate tax avoidance. For example, changes to strengthen tax treaties will prevent companies artificially avoiding a permanent establishment in New Zealand (thus avoiding tax in New Zealand). Treaty changes will also crack down on treaty shopping by multinationals and allow New Zealand to deny treaty benefits to companies that are using treaties to avoid tax.

33. The initiatives in the BEPS Action Plan will also allow New Zealand to impose more tax in cases where the current lack of transparency and information exchange between countries has meant the Inland Revenue does not have any visibility of profit shifting activities by multinational companies.

34. So, to the extent a multinational with a taxable presence in New Zealand is stripping profits out of its New Zealand operations through inflated deductions the OECD’s transfer pricing, interest limitation and hybrid mismatch rules will tackle this. To the extent a multinational has been relying on its tax information being outside the reach of the New Zealand Inland Revenue, country-by-country reporting will address this.

35. The OECD work is also focusing on the threshold for determining when there is a taxable presence in a country and particularly the concept of permanent establishment.

36. Changes to GST (for example, imposing GST on cross-border services and intangibles – such as digital downloads) also means New Zealand will be able to better impose tax on the consumption of the products of multinationals by New Zealand consumers.

37. However, the BEPS Action Plan does not go so far as to abandon the current international income tax framework based around the principles of “source” and “residence”. This means that the BEPS Action Plan does not yet tackle the thorny issue of companies (such as Google or Apple) who reach their markets via the internet, while basing their physical operations in a tax haven or low tax jurisdiction.

38. The current framework has been in place since the early 20th century. Under this framework, countries generally:

a. tax their residents on their income earned all around the world (the “residence” principle); and

b. tax non-residents on the income earned (or “sourced”) in their country – that is, income generated from assets located in, or activity performed in, their country. The result is that the ability of a country to tax non-residents on business income depends largely on the extent of their presence in that country.

39. A taxable presence generally requires either:

a. operation through a subsidiary resident in the country; or

b. operation through a physical “permanent establishment” in the country.

40. While this inability to tax business income in the absence of a taxable presence may appear to be a loophole, this rule is meant to be a pragmatic rule to keep businesses from being caught up in having to comply with local tax rules because of very limited interaction with a given country. For example, someone selling goods on Trade Me should not have to file a tax return for a country where they make one sale.

41. It could be argued that with the internet facilitating large volumes of sales without a taxable presence that this framework should be changed. However, making such a fundamental change to a century-old international tax framework would require a lot of thought and international agreement. It would fundamentally redistribute taxing rights to multinational profits and is beyond the scope of the BEPS project.

42. A few countries (particularly the BRIC[1] countries) are especially critical of the existing framework. They suggest that providing the market for sales should in and of itself be sufficient to attract a taxing right of some sort.

43. They argue that the established framework should be abandoned in favour of another framework such as the “global formulary apportionment” method, which would divide up taxing rights over a multinational’s total profit based on where the multinational makes sales or has property or activities. Under this type of approach, New Zealand may have more taxing rights over the profits of, say, Google, Apple or Facebook because they make significant sales in New Zealand, but less taxing rights over the profits of our major exporters. So it is important to keep in mind that a fundamental change to the international tax framework can cut both ways for New Zealand.

44. There is likely to be future pressure from some countries to move away from these existing principles towards, for example, global formulary apportionment, or more reliance on consumption taxes. New Zealand will continue to work with the OECD if and when these issues arise.

Consultation

45. Treasury was consulted in the preparation of this Cabinet paper.

Recommendations

46. I recommend that Cabinet note the contents of this paper and the attachments.

Hon Michael Woodhouse

Minister of Revenue

1. Brazil, Russia, India and China.

ATTACHMENT

Click on images for full size versions.