Chapter 4 - Rethinking the refund rules

Matters for discussion

The current imputation rules do not provide refunds for imputation credits that cannot be used. This chapter discusses the case for providing refunds for imputation credits in some cases – such as for tax-exempt organisations such as charities – and seeks comment on the following matters:

- Does the absence of a rule allowing a refund for imputation credits affect the type of investments a tax-exempt organisation makes?

- If rules were introduced to allow imputation credits to be refunded, it would be necessary to ensure they did not undermine the objectives of the imputation system. What checks and balances would a responsible refund mechanism have?

- Do other options exist to deal with concerns identified in this chapter?

4.1 New Zealand company tax is paid on income earned by New Zealand companies. This company tax paid can then be attached in the form of imputation credits to dividends paid to shareholders, so that, effectively, the company tax is seen as a withholding tax for the shareholder. If shareholders are subject to New Zealand tax they will have tax to pay on the dividend they receive and can use the imputation credits to pay all or part of that tax.

4.2 If, however, the shareholder does not have to pay tax on the dividend – for example, if the shareholder is a tax-exempt charity – the imputation credits cannot be used and cannot be refunded. The benefit of the imputation credits is lost to the shareholder. Moreover, the dividend income earned by the tax-exempt shareholder has effectively been taxed at the company rate rather than at the shareholder’s effective rate of zero percent.

4.3 One of the effects of this treatment is that tax-exempt organisations may choose investments that pay them a before-tax return (referred to as non-imputed income, such as interest) over those New Zealand shares that provide an after-tax return, such as imputed dividends.

4.4 This outcome is a concern for shareholders in New Zealand companies when those shareholders have a specific exemption from New Zealand income tax and consequently are not subject to tax on the dividends they receive. Registered charities are one example of a group that currently has a specific income tax exemption.

4.5 Similar concerns arise for shareholders who have tax losses or who are on marginal tax rates that are lower than the company tax rate. In these cases, however, the imputation credits that are not needed to satisfy the current year’s tax obligation on the dividend can be carried forward by the shareholder and used to meet future tax obligations on other income.

4.6 This chapter covers the current policy reasons for not allowing the refunding of imputation credits. It then considers the case for refunding imputation credits to organisations that have specific exemption from New Zealand income tax – for example, registered charities – and taxpayers with losses or tax rates that are lower than the company tax rate.

Current policy on refunding imputation credits

4.7 For reasons discussed in Chapter 2, New Zealand tax will continue to apply to foreign shareholders on the income they earn indirectly through their investments in New Zealand companies. This means that foreign shareholders should not receive refunds for imputation credits. Providing a refund to these shareholders would mean that any company tax paid in New Zealand would be effectively refunded.

4.8 In the case of New Zealand organisations that are not subject to tax on their income the issue is more complex, however. The concern is that these organisations are not able to benefit from the imputation system. This is contrary to one of the principles underpinning the imputation system, which is that shareholders should, as far as possible, be treated as if the income earned by the company were earned by them directly.

4.9 This concern with the current policy is frequently raised by the charitable sector as a reason for rethinking the rules that apply to refund of imputation credits.[5] The government is very aware of these concerns. In designing the imputation system, however, policy decisions were made that imputation credits should not be refunded, meaning that tax-exempt organisations and non-resident shareholders continued to be taxed at the company level on dividends received. Tax-exempt organisations are, in principle, no worse off under this decision than they were under the dividend system that applied till 1988.

4.10 The concern that has always existed when considering the case for refunding imputation credits is the pressure that could be placed on the company tax base by allowing refunds. Refunding tax credits could also create greater incentives for charities to be used in “tax planning” arrangements, contrary to policy.

4.11 Given the objective of taxing non-residents on the income they earn in New Zealand and that shareholders should, as far as possible, be treated as if the income earned by the company were earned by them directly, we now consider the case for refunding imputation credits.

The case for refunding imputation credits to tax-exempt organisations

4.12 Tax-exempt organisations are concerned that they cannot use imputation credits. They are effectively subject to tax at the company rate, 30%, on the income that is taxed within any companies they invest in. Example 6 shows the after-tax return a tax-exempt organisation receives from an investment in New Zealand shares, compared to what it would get if the taxation of the company income reflected its tax-exempt status.

4.13 As a result of the effects illustrated in Example 6, tax-exempt organisations are likely to prefer investing in products such as loans, bank deposits or shares that do not pay imputed dividends. Investment in New Zealand company shares, on the other hand, offers an after-tax return in the form of imputed dividends. Example 7 illustrates this point.

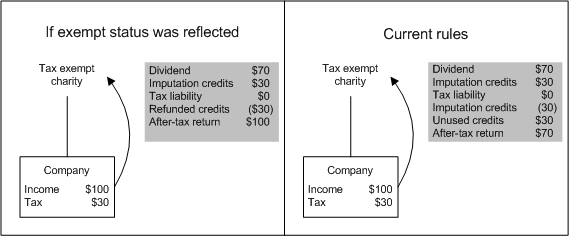

Example 6. How the imputation rules do not reflect tax-exempt status

A tax-exempt charity invests in a company that earns $100 profit and pays $30 tax at the company level. The profit is distributed to the charity. If the imputation system recognised the charity’s tax-exempt status the after-tax return would be $100.

Under the current imputation system, however, when the profit is distributed to the charity, there is an after-tax return of $70. The imputation credits of $30 are lost.

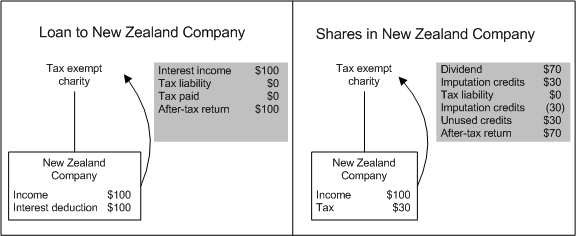

Example 7. How the imputation rules can affect the after-tax return on investments

The following illustration compares two investments that a tax-exempt organisation could make and the after-tax returns from both investments.

The case for refunding imputation credits to taxpayers with lower marginal tax rates or those with losses

4.14 Taxpayers with marginal tax rates that are lower than the company rate or taxpayers with losses may also have an interest in receiving refunds of imputation credits. They are unable to receive the full benefit of the imputation credits attached to the dividends they receive unless they have enough other taxable income. Imputation credits that cannot be used must be carried forward against future taxable income.

4.15 One important distinction between this group of taxpayers and tax-exempt organisations is that taxpayers in loss or on lower marginal tax rates may benefit from using the imputation credits in future income years.

4.16 While there is a cost to this deferral, the tax benefit of the imputation credits is not lost and, for financial reporting purposes, the value of these credits may be recorded as a tax asset. Therefore the concern is a matter of timing because tax is collected on taxable income at an earlier point in time than it would be otherwise.

4.17 The fact that the benefit of the imputation credits is not lost raises questions about whether it is necessary to refund to this group of taxpayers any imputation credits that remain unused in a current tax year.

Important considerations for refunding imputation credits

Scope

4.18 Consideration could be given to allowing imputation credits to be refunded to some or all of the groups that have an interest in allowing imputation credits to be refundable – including registered charities, other entities with specific statutory tax exemptions, taxpayers whose marginal tax rates are lower than the company rate, and taxpayers in loss.

4.19 Australia, for example, has taken the approach of limiting access to refunds to certain groups, including individuals who are Australian residents, superannuation funds and certain tax-exempt organisations.

4.20 To qualify for a refund under the Australian rules, tax-exempt organisations must have a physical presence in Australia, incur expenditure in Australia, pursue their objectives principally in Australia during the income year in which the distribution is made.

4.21 The Australian refund rules are supported by a range of anti-avoidance rules designed to ensure that the franking credits (Australia’s equivalent to our imputation credits) are not streamed to those that can seek refunds of the credits. If New Zealand provided for refunds, consideration would need to be given to these sorts of rules. It is obviously necessary to balance the complexity of the rules against concerns about the potential for tax planning opportunities. The rules in this area are also relevant in the context of streaming generally, as discussed in Chapter 3.

4.22 In considering the scope of introducing a refund mechanism it is relevant to consider whether such a move could be viewed as discriminatory. In other words, would it be acceptable to discriminate against non-resident shareholders over resident shareholders and between domestic shareholders in different tax paying situations?

“Tax planning”

4.23 Refunding imputation credits could lead to an increase in incentives for companies and shareholders to allocate imputation credits to shareholders that could access refunds. A concern with refunding imputation credits is that it would place additional pressure on the rules that ensure taxpaying shareholders in New Zealand companies continue to pay the correct amount tax on the income they earn in New Zealand.

4.24 For example, allowing imputation credits to be refunded to tax-exempt organisations could increase the incentive for certain taxpayers to temporarily transfer shares to tax-exempt organisations and then extract the refund, to the benefit of both parties – as illustrated in Example 8. If the type of arrangement described in the example resulted in less tax being paid by non-resident shareholders or higher marginal tax rate taxpayers (those that are required to pay tax at 33% or 39%), that would pose a risk to the tax base. The risk would apply equally to shareholders with losses.

4.25 The need for robust, potentially complex, rules to guard against tax planning opportunities must be balanced against the need to have legislation that is easy to understand and comply with.

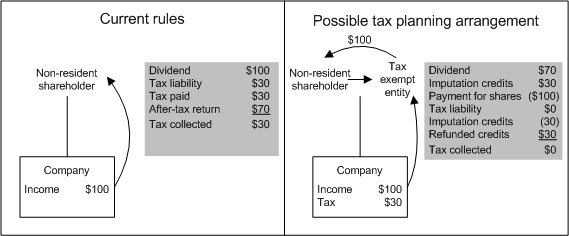

Example 8. Base maintenance problem with refunding imputation credits

A company that is 100 percent owned by a non-resident shareholder earns $100 profit and pays $30 tax. If these profits are distributed to the non-resident shareholder, there will be an after-tax return to the shareholder of $70. However, if the shares were sold to a tax-exempt entity before distribution, in the absence of suitable anti-avoidance rules the tax-exempt entity would be entitled to a $30 refund of tax (assuming a refund is available for the imputation credits). This tax refund is likely to be shared between the vendor and purchaser through the sale price of the shares. If the shares were sold for $100, the vendor would receive a $100 after-tax return. This result is inconsistent with the objectives of the imputation system, and the $30 reduction in tax paid would also be a fiscal cost.

Fiscal cost

4.26 It is difficult to determine the fiscal cost of providing refunds to the various groups identified in this chapter.

4.27 Refunding imputation credits to tax-paying resident shareholders that cannot use the credits against a current year’s tax liability (for example, if the taxpayer is in a tax loss position or has insufficient current year’s taxable income to use the credit against) is estimated to have a fiscal cost of $400 million. This estimate is based on data available for the 2006 and 2007 income years. This fiscal cost is likely to make it difficult for the government to extend refundability to this group. It should be noted, however, that these taxpayers can use the imputation credits against future years income tax liabilities.

4.28 Information about the value of imputation credit balances held by tax-exempt organisations is limited because they are not required to file tax returns. Allowing refunds for imputation credits, though, is likely to come with significant cost to New Zealand, without taking into account any changes in investment behaviour that may result.

4.29 There is also the question of the value of existing imputation credit balances and whether refunds should be limited to imputation credits generated by companies after the introduction of any refunds. The cost of not doing so is expected to be prohibitively expensive.

Fairness

4.30 If, because of concerns about tax planning or fiscal cost, decisions are made to exclude certain persons or organisations from any refund mechanism, that will add to the complexity of any rules and raise questions about discrimination. For example, refunds could be selectively made to organisations such as registered charities or charities that qualify for income tax exemptions. That, however, would discriminate against other tax-exempt taxpayers such as local authorities, qualifying friendly societies and amateur sports clubs.

Discrimination and non-residents

4.31 Similarly, establishing the grounds for refunding imputation credits is also important if New Zealand continues to tax income earned in New Zealand by non-residents. For example, consideration needs to be given to whether or not the extension of refunds to some or all New Zealand residents could violate discrimination prohibitions, either in domestic law or in international agreements (such as double tax treaties).

Matters for consultation

4.32 The question of refunding imputation credits to charities or other groups poses a number of complex questions and is not without its risks. Readers’ views about whether a refund mechanism for imputation credits would be suitable for New Zealand, in light of the issues outlined in this chapter, are welcome.

5 As noted in the October 2006 discussion document Tax incentives for giving to charities and other non-profit organisations.